Annexing the Jordan Valley

Israel’s coalition government contemplates redrawing the country’s borders, with America’s blessing. Senior ex-diplomat Dore Gold gives the inside scoop on how and why the status quo may not last long.

Armed with the U.S.-produced map that emerged from the Trump administration’s “Deal of the Century” process, Israel’s new coalition government will soon begin exploring possibilities for the permanent application of sovereignty to Israeli-controlled territories beyond the 1948 Israeli-Jordanian ceasefire line. The U.S. presidential election is a de facto deadline for any such change in borders, which would seem baldly reckless under a possible Joe Biden presidency. But an Israeli move prior to Nov. 3 might obligate a Democratic administration to deal with the proverbial facts on the ground, especially if they’ve been legitimized as American policy under the prior administration, and imposed through the political alliance between Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and former opposition leader Benny Gantz.

Annexation of densely populated civilian areas contiguous with places inside Israel’s internationally recognized boundaries, like the Jerusalem suburbs of Ma’ale Adumim and Gush Etzion, carries significant diplomatic risk. But that might not be seen as changing the map all that much, as decades’ worth of Israeli negotiators have assumed these places would always fall on the Israeli side of any future border. Another option would be to annex territory that prior talks haven’t succeeded in taking off the table, but whose strategic value might exceed the backlash risked by any change in the Israeli-Palestinian status quo. For annexation to make long-term sense, it would have to be territory whose permanent control is a demand shared across the Israeli political mainstream and which doesn’t have large Palestinian populations that have no desire to become Israeli.

With obvious strategic significance, and a relatively small population that is more or less evenly divided between Jewish and Palestinian inhabitants, the Jordan Valley fits the bill on all counts. Israel can even plausibly claim that annexation of the area between the West Bank ridgeline and the Jordan River would be a coordinated move, rather than a unilateral one: The Deal of the Century conflict-resolution framework foresees permanent Israeli control over the area and doesn’t condition a change in status on any peace agreement with the Palestinians.

A significant share of Israeli leaders, and the people who elect them, believe they now live in a region and a world where the consequences of annexation are manageable. By their logic, the Arab states need Israel too much to scuttle relations over what amounts to less than a quarter of the West Bank, especially when such an action would be consistent with an American peace plan that most regional governments have endorsed, whether officially or merely in practice. American recognition of Jerusalem as Israel’s capital and relocation of its embassy there, as well as endorsement of Israel’s annexation of the Golan Heights, were moves that were long believed to be too provocative to ever carry out. Instead, when they happened, they were all relative nonevents.

Gantz and Netanyahu are in general agreement on annexing the Jordan Valley. While opposition parties like Meretz and the Joint List, plus a smattering of other members of Knesset, might oppose such a move, or at least its timing, perhaps as many as 70 out of 120 MKs could be expected to vote in favor. Even some of the leading figures in the history of the more left-wing Labor Party might have agreed with a Jordan Valley annexation, at least in principle: Yigal Allon’s post-1967 war plan imagined the valley would remain in Israeli hands while much of the rest of the West Bank would be returned to Jordan. In his final speech to the Knesset, Yitzhak Rabin advocated an Israeli security border that extended to the West Bank ridgeline.

While popular among most Jewish Israelis and sanctioned by the Trump administration, annexation is hardly a done deal. Changing the status quo would risk international isolation and could even jeopardize Israel’s relationship with the United States. It took four years for the Trump administration to reverse many of Obama’s policies on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Biden might spend his term reversing the Trump team’s work, neutralizing the Deal of the Century the same way the Deal of the Century neutralizes much of U.N. Security Council Resolution 2334, which Obama’s foreign policy team engineered on its way out the door in December 2016.

While the possibility of a Biden presidency might make annexation seem even more attractive to Israeli decision-makers, it still might not be worth it. “Nearly everyone in the Israeli security establishment knows that maintaining Israel’s security control over the Jordan Valley does not require annexation, so applying sovereignty there does not end up conferring any new security benefits, but does create a new set of unnecessary risks to Israel,” Israel Policy Forum policy director Michael Koplow wrote by email. Israel’s leaders might look at the practicalities of annexation and realize they have less room to maneuver than they thought they did, and that the costs may be higher than they first appear.

“The IDF has to agree to those borders and needs to secure them, the Shin Bet has to buy in, and there has to be buy-in from the U.S.,” says Jonathan Schanzer of the Foundation for Defense of Democracies, outlining the process for deciding on what to annex and how. “This is a little bit like the dog that caught the postman. Now that they’ve finally gotten there it’s much more complicated.”

Jordan Valley annexation would be consistent with a long, multipartisan political tradition in Israel. But it is the activities of a single Israeli senior ex-diplomat that might shed the most light on why Israel now believes it is in a position to sweepingly alter the terms of its conflict with the Palestinians. Israel no longer sees the Oslo Peace Process as all that relevant or useful anymore. Enjoying newfound domestic political unity and a friendly White House, the country senses—rightly or wrongly—that it has entered a brief window for moving the status quo toward a different and, as far as many Israelis are concerned, more favorable paradigm.

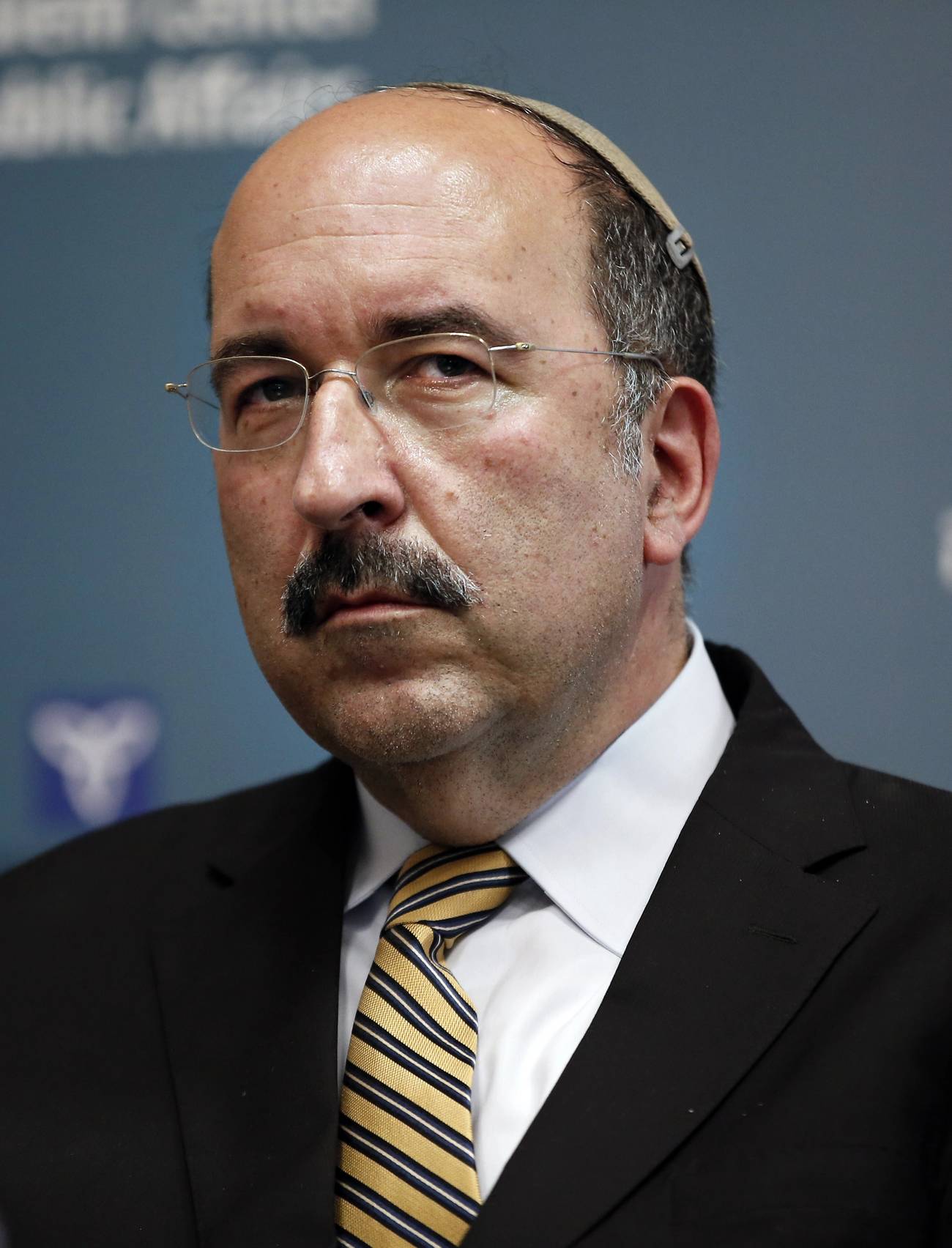

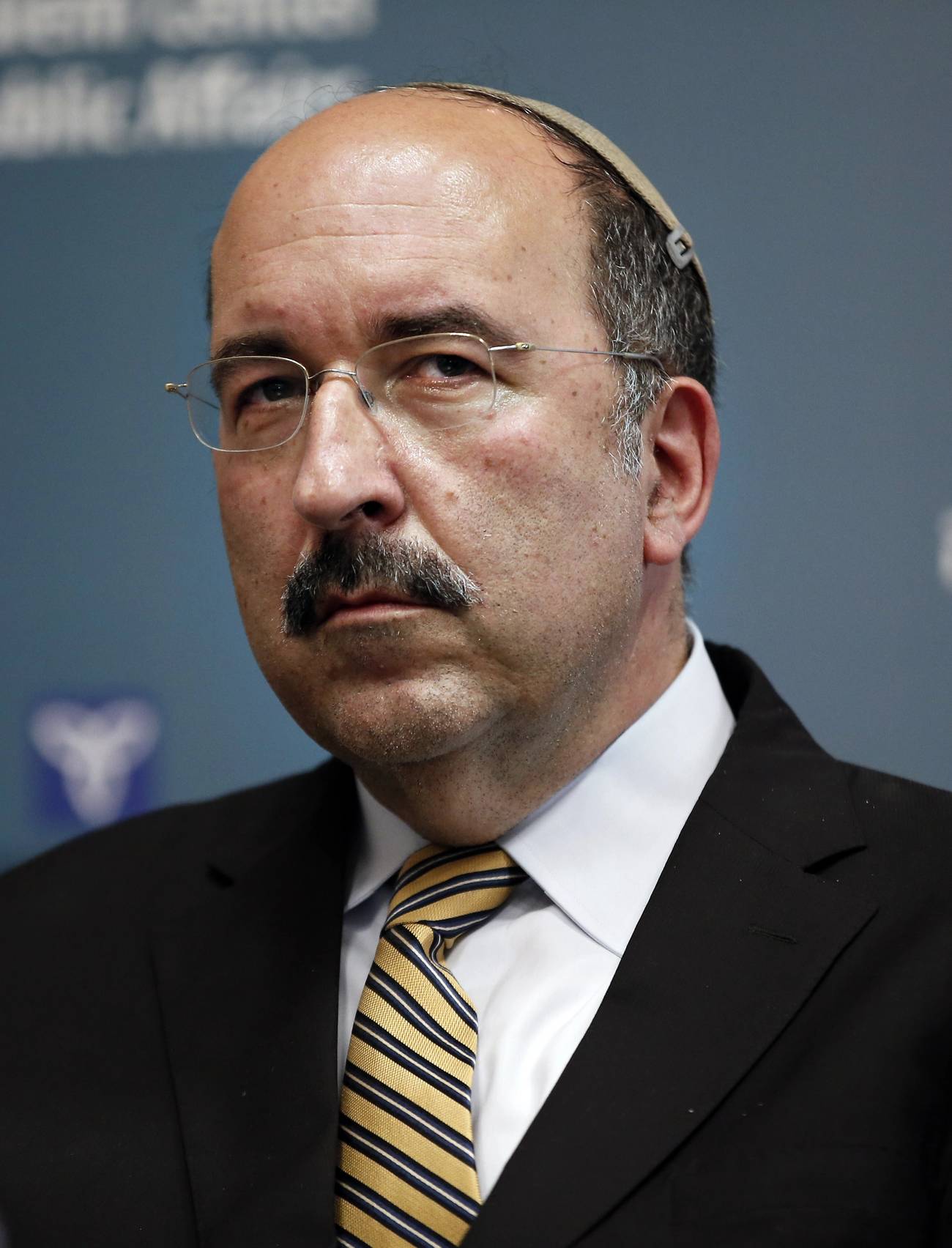

Dore Gold, Israel’s ambassador to the United Nations from 1997 to 1999, director general of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs from mid-2015 until October of 2016, and confidante to both Benjamin Netanyahu and the late Ariel Sharon, was one of a small number of Israelis outside of government who routinely consulted with Jared Kushner, Jason Greenblatt, and U.S. Ambassador to Israel David Friedman and their staffs in Washington or Jerusalem. In a February talk at the Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs, the think tank Gold has headed since 2000, Friedman cited Gold’s “three years of terrific collaboration and advice,” adding that “Dore and I have spoken countless times.” When the Deal of the Century was rolled out in a ceremony in the East Room of the White House on Jan. 28, Gold was there.

When reached for comment by email, Jason Greenblatt wrote, “Our team spent countless hours speaking with so many who are knowledgeable about the conflict, its complex and extraordinarily challenging issues, and prior efforts. That includes Palestinians, Israelis, and others from the Middle East and elsewhere around the world. We were fortunate to have learned a great deal from so many who were generous with their time. Dore Gold was one such individual. He has a great deal of knowledge about the conflict, the history of the region, and Israel’s significant security challenges. Speaking with him, as with so many of the others we spoke to, was very helpful. Ultimately, however, the plan was written by the team at the White House, and reflects President Trump’s vision to create a realistic and implementable way to resolve this long-standing conflict.”

Gold might have anticipated that the Americans would view him as an extension of Netanyahu, his former boss and close associate. “This is as true in the Israeli system as it is in ours: Once you work for the executive you never really stop,” said Jonathan Schanzer, who described Gold as someone who “looks at issues that aren’t being covered but should be”—the Jordan Valley among them.

On a matter like the Jordan Valley, “I wouldn’t just take the position by myself—that was the position of the prime minister,” Gold explained. As a major figure who was no longer in government, Gold was able to operate under a less restrictive set of pressures and work with greater flexibility than a traditionally credentialed diplomat. “If you have a sensitive negotiation going on, you’re very reluctant, whether you’re in Washington or Jerusalem, to share that information with fellow government workers because if they haven’t been formally brought in, they are prime candidates for leaking,” Gold explained. “Think tanks provide a kind of protection for that, and we had virtually no leaking.”

Gold said he had a clear objective in engaging with the American team. “I was in it to try to help formulate a plan that would provide a consensus basis for Israel’s future borders.” He said that while the West Bank arose frequently in his discussions with the Americans, the Jordan Valley was not addressed in detail until the tail end of the process. Convincing the Americans of an Israeli position “wasn’t automatic,” Gold recalled. He described Jared Kushner as “very, very smart. But you have to be persistent in presenting your views to him. A lot of my views have been molded by years of work in this area. His opinions were formed with a much shorter exposure.”

Eugene Kontorovich, a legal expert and director of the Jerusalem-based Kohelet Forum, who also met with members of the American team, did not get the sense they entered the process seeking a specific outcome. “It was hard to tell what their views were at the beginning of it,” said Kontorovich. “I think they came into this in fact-finding mode, without any preconceived position.”

The Jordan Valley was hardly a new issue for Gold. In 1997, he accompanied Netanyahu to the Map Room of the White House, where they presented members of President Bill Clinton’s peace process team with an “interest map” of the West Bank that highlighted areas Israel believed to be of critical importance, the Jordan Valley included.

Still, the Clinton Parameters, issued in the final days of Clinton’s presidency, indicated that the valley would be under the control of an eventual Palestinian state, following a transitional period in which an Israeli and international military presence would secure the area. From then on, negotiators explored a range of alternatives to Israeli sovereignty: Israel could potentially keep bases inside Palestinian territory for a set period of time, or maintain sensors and early warning systems. Israel, unlike the Palestinian Authority, accepted the Clinton Parameters, but Gold never bought its solution to the Jordan Valley.

“My approach is based on a deep respect for the founding fathers of Israel’s national strategy, starting with Yigal Allon, going to Yitzhak Rabin, going to Moshe Dayan, going to Ariel Sharon,” he explained. “When I see what they left us as a legacy in writing, I can’t ignore that and say we’re going to defend the Jordan Valley with flying saucers.”

Until the American invasion of Iraq in 2003, it was believed Saddam Hussein’s army could cross the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan and reach Israeli-controlled territory in around 36 hours. Even with that scenario foreclosed, Gold thought Israeli planners needed to work across a longer time scale than the life of a single leader or even a single regime—after all, Israel has more control over where its forces are arrayed in the Jordan Valley than it does over who rules in Amman or Damascus 10 years from now. “Military planning, especially strategic planning, should never be scenario-specific,” Gold said. “What do you do if Saddam is defeated? Does your whole national security doctrine change?”

Gold’s answer was no. In the mid-2000s, Gold argued for Israeli control of the valley and other territories to experts in Washington, Berlin, and Beijing. As the Arab Spring plunged the Middle East into a new era of uncertainty, Gold remained a rare voice that still bothered to stake out a clear public position, aimed at audiences outside of Israel, in favor of Israeli control over the valley. In 2011, the Jerusalem Center published a report entitled “Israel’s Critical Security Requirements for Defensible Borders: The Foundation for a Viable Peace.” The partly Gold-authored document, which was also published in German and Chinese, emerged during a time when the Obama administration’s stance on the conflict, and the new wave of protests and crises across the Middle East, made Israeli changes to the territorial status quo seem like a distinctly faint near-term possibility.

Israeli action wasn’t a sure thing under a Trump administration either. When I asked Gold about points of disagreement between himself and the Trump team, he paused for a moment, and said: “I personally had the view, which got backing from the prime minister’s office, that in places like the Jordan Valley where Israel had the highest security interests it would have to seek actual sovereignty over the territory. The idea of putting extraterritorial military positions on the soil of Palestine was not a model I was very comfortable working with.”

This argument repudiated decades of peace process doctrine, which defaulted to treating the valley as territory in a future Palestinian state. It also represented a victory over a certain long-standing American view of what their ally should be willing to accept in a final agreement. “There’s been a whole cottage industry working assiduously to get Israelis to accept a narrower definition of their national security needs,” Gold claimed.

Gold is in a unique position to glimpse the peace process’s diminishing returns, in part because of his work fostering ties between Israel and Arab countries that have no official relations with the Jewish state. In a time when Israel had overcome its conventional enemies, signed treaties with Jordan and Egypt, and largely eliminated the threat of terrorism from Gaza and the West Bank, peace with the Palestinians was often sold as the only means of reconciling Israel with the remaining Arab and Muslim governments that did not recognize the country’s right to exist. With Palestinian militancy largely a controllable problem, ties with the broader Arab and Muslim world were often presented as one of the peace process’s remaining value propositions.

Gold saw that this wasn’t entirely true: In fact, Israeli ties with the Arab world and achieving a permanent peace agreement with the Palestinians didn’t fully depend on one another, especially as the possibility that such an agreement may in fact never be reached becomes more commonly accepted in mainstream foreign policy circles.

Paradoxically, as the likelihood of a peace agreement recedes, Israel may find it easier to reach mutually beneficial understandings with its Arab neighbors on points of common interest and concern, even if the lack of a resolution with the Palestinians limits how far these relationships can go. Gold recalled a diplomatic meeting with a counterpart in an Arab capital in which their bulleted talking points, on topics like threats from Iran and Sunni Islamist groups, were almost identical. “I personally believe that [the Jordan Valley] is not of paramount importance to the Gulf Arab states,” he said. “But it is not in our interest to put any Arab state in an awkward position.”

There’s also an inner world to strategic thinking in the Middle East that outsiders barely get to glimpse, and whose contents are not always what global decision-makers might believe them to be. “You know, if you get a senior Jordanian military figure to the Council on Foreign Relations in New York, he’s not going to pour out his guts and say, ‘we want Israel to protect our eastern flank.’ It’s not going to happen,” says Gold. “Whatever he believes, he’s going to keep it to himself.”

Armin Rosen is a staff writer for Tablet Magazine.