Kurdistan and Israel

Kurdistani Jews are caught between the Jewish state and the ethnonationalist ambitions of its Middle Eastern neighbors

In October 2015, a man named Sherzad Omer Mamsani emerged into media consciousness. He claimed to be a Kurd of mixed Jewish and Muslim heritage, and soon began claiming to be the Kurdish representative of Jewish affairs. “He came here to do business; when I met him, he never mentioned he was Jewish,” said Mordechai Zaken, an Israeli of Kurdistani Jewish origin who is today a senior Israeli political figure dealing with minority relations. Mamsani’s own version is vaguer, more lyrical. “In Jerusalem, I smelled the scent of thousands of years of ancestry,” he stated, “it was like a rebirth.”

Zaken saw a pivotal discrepancy, though. “When he went to the U.S. he was saying we want to help the Jewish community of Kurdistan,” he explained. “There is no Jewish community of Kurdistan! There is none. And he kept claiming there was one.”

When confronted with a highly motivated opportunist, who at the worst would promote the harmless fraud of a Jewish Kurdish community, the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) gave him an orange light: Mamsani was the only extant avatar for the Jewish angle into the case for Kurdistan. This allowed his myth to grow in a shadow space between self-appointment and officialdom.

Mamsani staged a ceremony linking the expulsion of Jews from Iraq with the Holocaust, and invited the American consul to another at which Zaken says he set up a menorah with the wrong number of candles. “If you look at his Facebook page you can see references earlier to the Quran. He’s an opportunist.”

Mamsani’s efforts were not just self-promoted, but covered by Rudaw, the dominant English-language Kurdish media outlet, lavishly sponsored by Nechirvan Barzani, nephew of the Kurdish leader Mustafa Barzani. The understanding of Mamsani as a legitimate figure was lobbed from perch to perch—from observer to reporter and back again—in a feedback loop of lazy opportunism and low-level interest. All it took was a face that in a mute way expressed an ancient, suppressed drama of an unspecific yet resonant kind.

And what about the fact that the KRG’s head of religious affairs, Mariwan Naqshbandi, also endorsed Mamsani’s rhetoric about the existence of a Jewish community in Kurdistan? “Not very smart. I was very upset with them,” Zaken told me. The image created by Mamsani and those who covered him shaded into the reality of KRG policy, as a harmless yet sophisticated and intriguing-sounding lie that could further entrench Kurdistan’s claims to be an independent multireligious state.

***

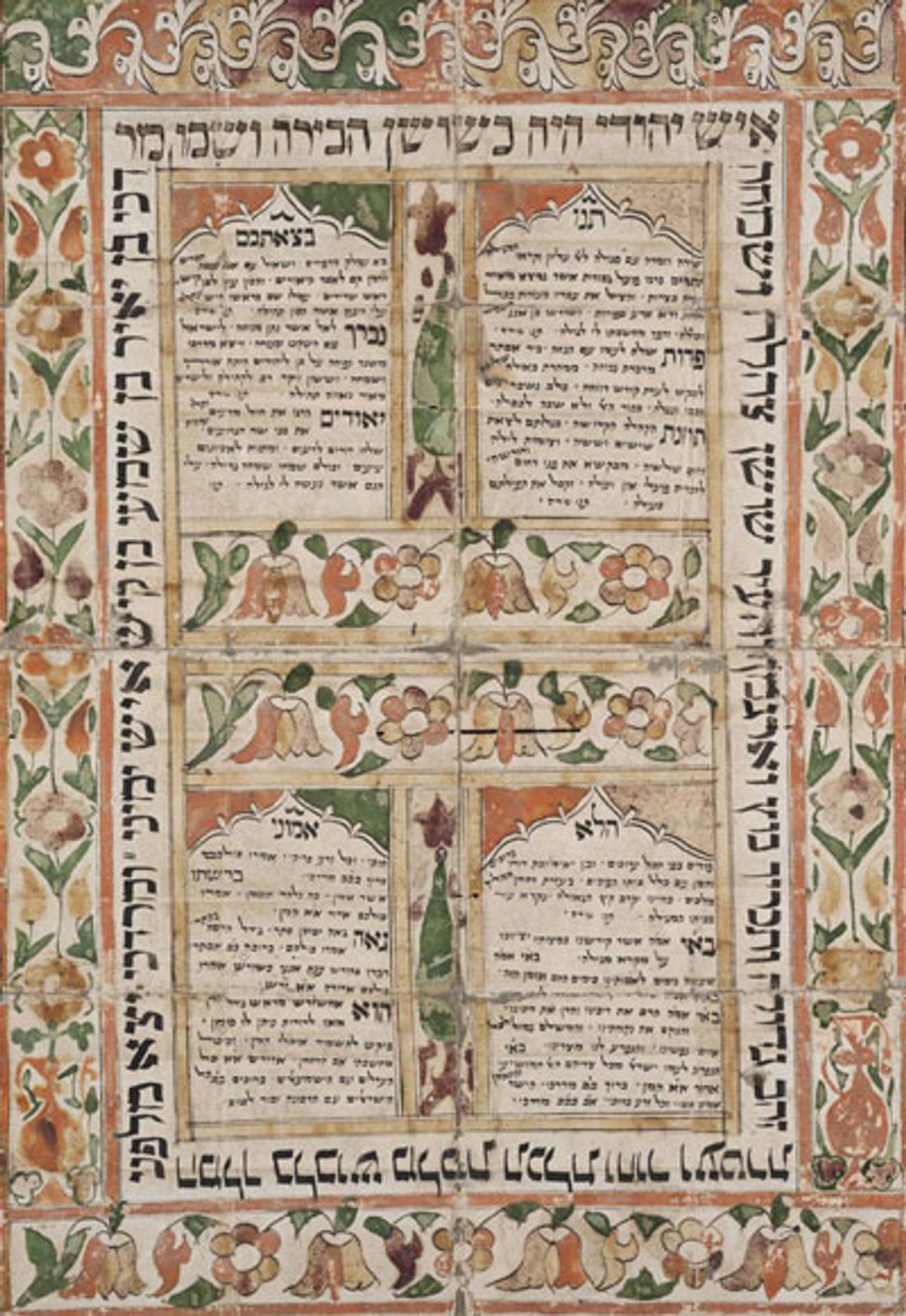

Jews were first brought to Assyria and Babylonia beginning in the eighth century BCE, by migrations that are usually referred to from a historical Jewish perspective as “captivity”—a manifestation of policies that moved populations across these empires for imperial enrichment and advancement. The Babylonian captivity cast a long shadow into the Jewish consciousness, and played a significant part in the development of Jewish culture. In Iraq, Jews developed the Talmud and their own dialect of Aramaic, and the Torah is filled with references to Babylon and Assyria. A post-Assyrian kingdom named Adiabene, with Erbil as its capital, had Judaism as a state religion and Aramaic as its official language.

A Babylonian Jewish community survived the Arab conquest, the Mongol invasion, and the Ottoman Empire. By the 19th century, a major Jewish population had moved to Baghdad while other Jewish communities remained scattered across difficult terrain in what is today northern Iraq and adjacent territories in Iran.

Historian Mordechai Zaken has written of his ancestral community that during modern history “they had been heavily dependent on the patronage and protection of their chieftains,” a status that also entailed accepting the reality of “Islamic hostility toward Jews.” But despite a fundamentally inferior social status, the sense of which increased in the 19th century, some Jews flourished within a Kurdish world—especially in agriculture. Pogroms took place, but there was no genocide against Jews by Kurds.

David D’Beth Hillel, a Lithuanian Jewish traveler who went to Kurdistan in 1827, wrote of a Jewish community in Zakho, “three days journey to Assyria, or Mosul,” who were “ignorant both of the Hebrew language and customs.” He saw “Nazareens [Christians, in this case Assyrians] who follow the same customs and have the same [Aramaic] language” as the Jews, separated from “Coordish families, denominated Mahometans, speaking their own language.” By the time the final migration of Kurdistani Jews to Israel took place in the early 1950s, they comprised around 25,000, with around 8-10,000 having already made aliyah.

But the story of the Jews of Kurdistan and their legacy did not end there. Just outside Mahane Yehuda, the old market of Jerusalem, I recently entered a café filled with old men, and began searching for Jews from Kurdistan. A man drinking a can of Goldstar—sitting by a refrigerator, behind the clack of backgammon—raised his hand, and I took a seat next to him. I asked him questions in English, and my translator, an Iraqi Jew, translated into and from Hebrew.

He told me that he made aliyah when he was 12 from Zakho: “I know every place in Kurdistan: from the Russian border to the borders of Turkey and Syria. I remember everything.” His memory was steeped in anecdote—history as something that doesn’t require any explanation beyond the space in which it happens—undulled by the mental shroud of concepts and categories.

In describing life for Jews among Kurds, he referred to the events and figures that directly shaped their lives: their economic ties to Kurds; the mercy or cruelty of particular sheikhs. “In our area there were ‘Arab’ [i.e., Muslim Kurdish] leaders who protected us. But whenever Muslims would come from outside, from Turkey for example, they would hit us. They were outraged that we had shops and businesses in Zakho.” His usage of the term Arab reveals that religious and tribal identification persisted here as a dominant form of social organization into the era of nation-states. That Arabs were the dominant group among Muslims in general meant that for categorical purposes, from a Jewish perspective, Muslim Kurds were effectively Arab—their Kurdishness was of primarily linguistic, not ethnic consequence. “In the 1940s, when the name of the state of Israel began to sound, Muslims started to hate us. Kurds, however, were neutral,” he continued, a point that would recur throughout my conversations.

The ultimate kindness the Kurds performed for the Jews was allowing them to escape the nightmare of Iraq and return to Israel, in contrast to the institutionalized anti-Semitism and violence directed against Baghdadi Jews in the years prior to their flight. This collective memory, of a rare act of empathy by a majority group towards Jews, has percolated up to the political class, where it is taken as evidence of the moral caliber of Kurds, as well as their capacity for sympathy based on minority suffering and self-determination.

He told me about his trip back to Iraqi Kurdistan in the ’90s, when the no-fly zone meant travel was safe, though clandestine. He travelled across the area—Dohuk, Alqosh, Akre, Erbil, Sulaymaniyah. “I went to enter our synagogue in Zakho. Muslim families now live there: I couldn’t enter because the husband was not present and his wife was alone inside. But they invited me to have a look next afternoon, when the man returned.” I asked him how it felt returning to the country of his birth. “Very satisfying. The same Arabs [i.e., Kurds] who hated us, now host us and treated me like a king.” He echoed my translator’s English translation: “King. King!”

Another old man, wearing a striking gold cap, overheard us talking, and joined us. He came to Israel at 13, he said, from a village on the border with Iran. His father made shoes. My translator told him I’m Assyrian, so I clarified that my immediate national ancestry on my father’s side is Baghdadi.

He started singing in Assyrian: “I climbed the mountain in a caravan!”

For the first time in my life, I spoke Assyrian to a Jew. I started by asking if he spoke Assyrian with his parents. Yes—and he told me he had Assyrian friends, and that I look just like them. My Assyrian Aramaic and his Jewish Aramaic were largely mutually intelligible.

“What’s the name of the language we’re speaking?” I asked. “Ashouri (Assyrian)” he responded. He was rusty after decades of Hebrew. “You’ve forgotten it?” I asked. “I have forgotten it,” he responded in melancholy Assyrian. “I understand what he’s saying, but it’s hard to respond,” he told my translator.

I asked him if he saw himself as different to Kurdish Muslims ethnically. “Yes: the language is different. We spoke Assyrian, but the Arabs [Kurds] didn’t understand us. When the Arabs [Kurds] spoke to us in their language [Kurmanji], we as Jews understood. When we spoke to them [in Assyrian Aramaic], they did not understand us.”

“We, with Assyrians,” the first old man explained, “were like a family, with Muslims on the other side.” But he rejected being referred to as Iraqi.

When I asked him what he called himself ethnonationally upon arrival in Israel, he said “Kurdi,” or Kurdish. Why? “Because we are not Iraqi. Kurdistan is a big place: much bigger than Iraq.”

The ultimate kindness the Kurds performed for the Jews was allowing them to escape the nightmare of Iraq and return to Israel.

Here, I got a sense of the geographical imagination of this community, how the string of Kurd-dominated mountains and the villages and towns extending from their plains were much more part of their historical-cultural world than Baghdad, which after all only began to assert its central authority after the establishment of the Iraqi state. “I dream all the time to return to Kurdistan,” he said, “to see our places.” He also returned, in 1994. His father’s brother was still there. The uncle had converted to Islam.

In the apartment of Yona Mordechai, two Kurdish flags (the ones most associated with Kurdish nationalism in Iraq) sat on computer terminals as if they were ramparts. Mordechai, who came to Israel from Zakho aged 12 in 1950, is a community leader who speaks in favor of Kurdish independence. He teaches spoken Aramaic to his community, including younger members born in Israel and has written a Hebrew-Aramaic-English dictionary, compiled partly by extensive interviews with Kurdstani Jews in Israel. His relaxed, jovial tone about Kurdistan—whose imagined future basks in the warm glow of his childhood memories—can also be seen at pro-independence rallies which he and his peers organized last year: a relatively rare and colorful display of interest by Israelis in their country of recent origin, let alone of its political status. We spoke in Aramaic, with some help from a Hebrew-English translator.

“I remember everything,” Mordechai said of his 12 years in Zakho. “Our education was all oral. One of us learned from the other, by mouth. We learned in knuhsta [the Aramaic version of the word knesset, or assembly, here meaning synagogue]—the Torah, the Tanach—but didn’t understand the language. We would read the words in Hebrew, but didn’t understand their meaning, because we spoke in Aramaic,” he added. “When I first heard Christians also speaking Aramaic, I was very surprised.”

The term he used in Aramaic to describe his people—kurdinaye (Kurdistanis), as opposed to kurdaye (Kurds)—is one I had never heard, and which Efrem Yildiz, professor of Hebrew and Aramaic studies at the University of Salamanca, confirmed is a coinage particular to Kurdistani Jews. It speaks to the circumstances and perceptions of the community: the existence of their internal world rooted in the inheritances of ancient Judaism and Assyria and Aramaic and incubated among a Kurdish majority. It was a world they carried with them to Israel, and which is now disappearing along with the last memories of it.

Despite telling me that relations with Muslim Kurds were “not so good,” Mordechai had a tender feeling for what he depicted as an almost magical corridor created for his community by the Kurds in allowing them to go to Israel freely. “Every day,” he said, “we prayed for a return to Jerusalem.” In allowing Jews to fulfil the dream of return, Kurds had revealed some fundamental aspect of their sensitivity, and this legacy of sympathy was depicted as an inherent harbinger for future relations. He blamed Turkish Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan for not allowing the Kurds to become independent, and is aware of the Iraqi seizure of oil fields in the fallout, but remains committed to Kurdish independence.

“Barzani is a Kurd before he is a Muslim,” he proclaimed. “With Kurds [i.e., Kurdish nationalists] we can have a good relationship, but with Muslims [i.e., Islamists] there are problems. We remember that especially with the Christians of Kurdistan, we had a good relationship. And most Kurds love Israel; and most Israelis love Kurds. We remain with them,” he said, using the Hebrew saying: “fire in water.”

***

With the ingathering of Jews, the Jewish experience in all its obscure diversities could be—perhaps needed to be—sequenced, patterned. This mental and social process referred to history, geography, ethnicity and religion. One form it took was to invoke deep civilizational backgrounds for Mizrahi Jewish communities. The term Babylonian Jew—used in Israel’s national Iraqi Museum and other official contexts—harks back to the Old Testament, bringing the person encountering it back thousands of years to the departure of Jews from Israel and therefore the reversal of it by Zionism. It demonstrates a more ancient vision, a refusal to play the modern game. In opting for Babylon, the seat of Jewish learning and culture in what became Iraq, rather than Assyria, with its more destructive, subjugating, humiliating connotations, it suffuses Iraqi Jews with a cultural substance that is movable according to their own agency. It implies that the state formation of Iraq never included Jews—that Jews predate the state, and therefore have the right to be mobile from it, loosened from its attachments. It both affirms and reclaims the rejection of Jews by Iraq.

“Kurdistan” would, in time, become a reverse projection: not merely an attempt to reclaim history—to use the currency of the ancient to retroactively dignify an experience—but to change the future. It would become, more practically, a way of binding Jewish unease with the potential for collective Arab power with a justifiable thesis that minorities deserve more political authority in the region. And yet Kurdistani Jews came from differing backgrounds and experiences that would only later coalesce into a firm—yet geographically supple and expansive when necessary—idea of Kurdistan per se when the premise of a Kurdish state came into being. Kurdistani Jews would eventually bear witness to the good treatment Kurds gave Jews as a reason for Israel to support a Kurdish state. In the years after the arrival of Jews from Kurdistan, however—with no fashionable Kurdish cause, and no chronically ingrained sense of Iraq as an enemy state—the Kurdish label held a negative connotation.

“The term ‘Kurd’ was insulting. To be a Kurd was to be looked down upon: ‘don’t be Kurdish’ meant don’t be ignorant,” the veteran Haaretz journalist Danny Rubinstein told me. “But when they went to shul, they knew things by heart. And many Israeli writers were fascinated by this.” The lack of an experiential connection with the near east, coupled with the startling encounter with one of the smallest, obscurest, and perhaps the only illiterate Jewish community in the world attracted the Ashkenazi literary imagination. Israel was now establishing a national literature that was in touch with Jewish legacies forged and forgotten in exile. Kurdistan, owing to its unknowability, became a canvas for the Israeli imagination.

Edo and Enam (1950) by S.Y Agnon provides a vivid window into the absorption of Kurdistani Jews into the Israeli mind. For Agnon, they are a living museum of ancestral continuity: “If you wish to see Jews from the days of the Mishnah, go to the city of Amadia,” an ancient Assyrian-Jewish city near the Iraqi border with Turkey. The Kurdistani Jews’ mysticism is associated with a raw, elemental, nearly wild way of life: “Shepherds move about, men of great stature with long hair; they sleep with their heads in clefts of the rocks, and do not know the laws of the Torah.”

In Israel, Kurdistani Jews became specialists in stonework and construction. Rubinstein told me about a slightly older Kurdistani neighbor of his with whom he worked in construction after military service. “When he got his first check, the father of his friend used a sign instead of a signature. And my friend thought—if he can make it while being illiterate, so can I.” His friend went on—as did many Kurdistani Jews—to prosper in construction.

I visited Amatzia Baram, professor emeritus at the Department of the History of the Middle East at the University of Haifa, in his Haifa apartment to discuss the history of Israel-Kurdish relations. On his balcony, where he comes to contemplate the problems of the Middle East across a gleaming view of the Mediterranean, Baram has constructed and installed a fake owl to keep away pigeons. It works.

“From 1948, we started to eye the Kurds to see if we could build something,” he told me. “But during the monarchy,” which ended with a military coup in 1958, “Israel was not interested in actively undermining Iraq, especially given that Nuri-al Said [the final Iraqi prime minister under the monarchy] was trying to reach some agreement with the Kurds, and no major attack on Israel had yet been launched by Iraq.”

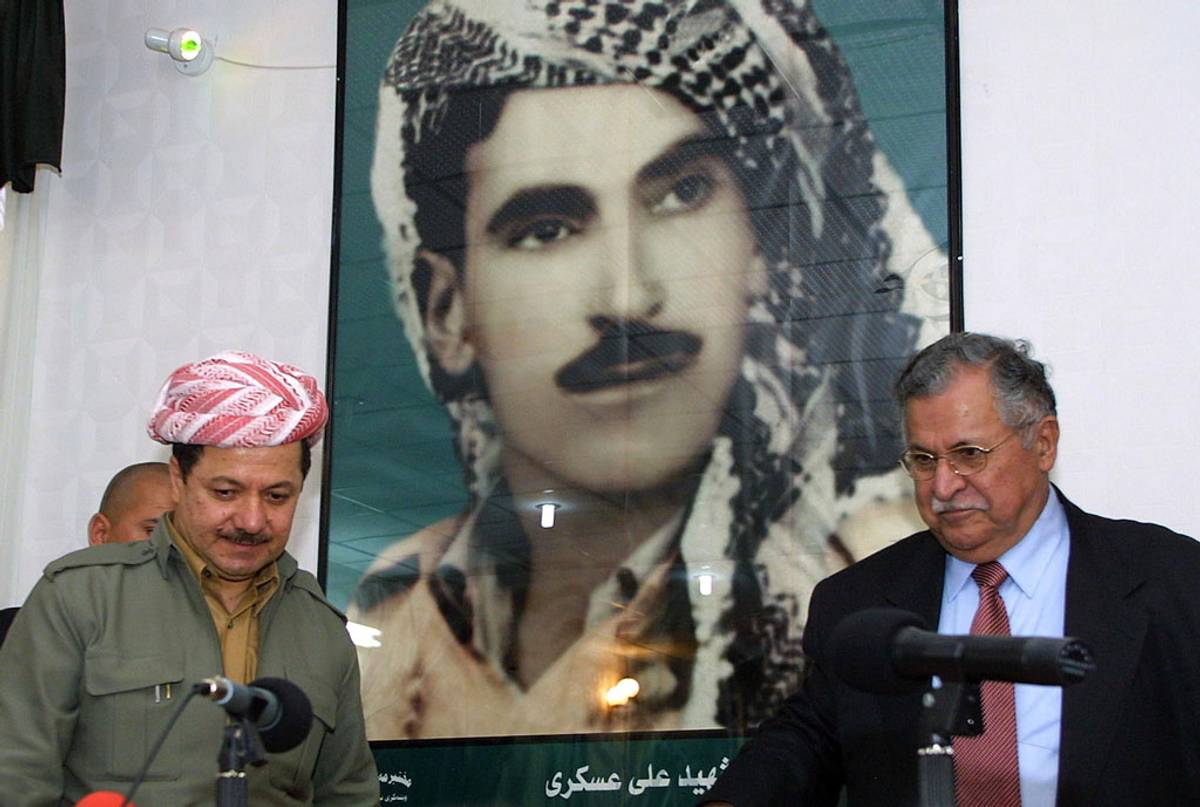

In 1961, in response to the first major uprising by Mullah Mustafa Barzani—founder of the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP) and father of current KDP leader and former KRG President Masoud Barzani, who Baram says is “obsessed with his father’s legacy”—Israel exerted “extreme effort to court the Kurds militarily.” This entailed providing support, through Mossad and A’man, to the Peshmerga rebels, as well as obtaining military intelligence on the Iraqi army through the Kurds, according to Samuel Katz’s Soldier Spies. Munir Redfa, the Assyrian fighter pilot who defected from the Iraqi army by flying a MiG-21 fighter jet from Iraq to Israel, was smuggled out with Kurdish assistance.

“With the Ba’ath takeover in February 1963, and with the preparation of plans by the Nasserist General Abdul Salam Arif [President of Iraq from 1963-66] to unite Iraq and Egypt, Israel got worried,” Baram continued. “Until March 1975, Israel helped the Kurds in every way they could. Barzani did not help us in the Yom Kippur War of 1973, which greatly disappointed us—but we understood his position. There were things the Iranians wouldn’t allow, but whatever they did, we would do.”

David Karon, the Mossad spymaster who became the first major Israeli liaison to Iraqi Kurdistan, would always report back to Golda Meir that Mustafa Barzani’s message was simple: “Give us independence.” There is a direct line between that plea and the anger of this Kurdish man protesting in Erbil after the referendum: “America and Israel promised us, but they are liars.”

In March 1975, Saddam Hussein met with the shah of Iran in Algiers to discuss the Kurdish question. The shah agreed to withdraw support for the Kurds in exchange for Saddam giving up Iraqi water, and moving the border along the Shatt al-Arab, a river between Iran and Iraq, in favor of Iran.

“Mustafa Barzani had to evacuate all of his forces into Iran immediately. We had a few people there, and they were immediately folded back into Iran, and flown back to Israel. After that point, Israel couldn’t do anything useful for the Kurds because there was no access.”

In 1991—in response partly to an attempt to roll back Saddam in the wake of the Iran-Iraq war and the invasion of Kuwait—British and American forces established a no-fly zone in Iraqi Kurdistan, creating a “safe haven” for the mass return of refugees, and establishing a military presence that kept the Iraqi army at bay. But the consolidation of Kurdish nationalist authority under international auspices in Iraq quickly enshrined and accelerated the tendencies of KRG politics—treachery, tribalism, violence, land theft, corruption, patronage systems so tightly knit they render the creation of coherent political institutions impossible—culminating in an intra-Kurdish civil war from 1994 to late 1997. The civil war was formally resolved in September 1998 by establishing a duopoly of power between Barzani and Jalal Talabani, who led the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK) until his death last year. Until today, Barzani and the PUK preside over effectively discrete mini-fiefdoms.

The establishment of the KRG allowed Israel to resume direct, though still clandestine, engagement with Iraqi Kurds, which had been put into abeyance since 1975. After the borders of Iraqi Kurdistan were opened to Israelis, Muslim Kurds began to contact members of the Israeli intelligence who were present on the ground in the KRG, claiming Jewish ancestry.

Yona Mordechai was a member of the committee vetting these potential Jews. “I knew that almost every Kurdistani Jew had left by 1951-2—I was part of that migration,” he told me, “so it was hard for us to believe there were any Jews remaining there.”

Their families in Israel, however, pressed firmly for their relatives to make aliyah. The intelligence services and the Jewish Agency finally agreed to bring into Israel around 1,700 Muslim Kurds with Jewish ancestry, mainly through secret air operations. “When I asked them for evidence of their Jewishness—a ketubah, for instance—they could produce nothing. They instead named people in their family, citing a Mordechai or Moshe. I told them I had a neighbor named Ibrahim: Does that mean I’m Muslim?”

All of these prospective Jews were practicing Muslims, and most had likely fabricated their Jewish ancestry, which was usually claimed through a grandmother. Measures were taken to help them “become Jewish” as Mordechai put it, including translating instruction books into Kurmanji, to no avail. “There is an absorption center, and nearby a Muslim village named Abu Ghosh,” said Zaken. “They would go from the absorption center to pray in the mosque.” It soon became clear that the vast majority, if not all, of the emigrants were seeking to secure state benefits—including significant payments their families gave them in order to settle in Israel—and an Israeli passport. Once these were secured, almost all left for Europe or returned to Kurdistan.

“I am no longer in touch with a single one of the arrivals,” said Mordechai. “With their families, yes—but not with the individuals who came from Kurdistan. The families are very disappointed in the actions of these people, and I personally found it disappointing.”

***

Until the recent Kurdish independence referendum, which led to the Iraqi government retaking the oil-rich city of Kirkuk, Israel purchased as much as three-quarters of its oil from the Iraqi KRG. Today, Israel still accounts for around a third of KRG oil exports. The oil is usually carried by unmarked oil tankers, or tankers bearing a Maltese flag, from Ceyhan in Turkey—sometimes stopping in Valletta, Malta, or Alexandria, Egypt—to Ashkelon, the oil port in Israel near the Gaza Strip. The vessels discharge the oil and reappear on the radar hours or days later. The Israeli government denies buying oil from the KRG.

“The original reason that these deals were secret was that Israel was effectively buying ‘stolen’ oil, against Iraq’s wishes, at sub-OPEC prices,” said Idan Barir, journalist and researcher at the Forum for Regional Thinking. The opportunity to take advantage of Iraq’s nonrecognition of Israel coincided with economic benefit. “These prices were lucrative for Israel, as well as the KRG, because the oil was left over from their quota agreed with Iraq. Both sides enjoyed it, and the Turks enjoyed it as middlemen.”

In July 2014, Barir visited Ashkelon to look into the Israel-KRG oil trade, and was held and questioned by an unidentified security agent at the oil port after a guard lost patience with Barir’s probing. But after that, a journalist friend of Barir asked and received an official response from the Israeli Infrastructure Ministry, stating that Israel is not part of any deal with the KRG. While some oil may have reached the port in Ashkelon, it was purchased privately by Israeli businessmen, and was only stored in tanks that were leased by the state, but not state owned.

Perhaps more significantly, Israel has provided the KRG with internal security assistance since the establishment of the no-fly zone. That assistance was a contributing factor to the almost complete absence of terrorism in the Iraqi KRG from 2003-2014.

Colonel Amir Goren, who served in the IDF for over 30 years and is now 53, describes himself as an “international anti-terrorism expert,” providing “tailored solutions” to “combat, physical and technological needs” for “public and private organizations” in several geographies. He led a group of Israelis who trained Iraqi Kurdish security forces and Peshmerga from 2004-2006, working as a subcontractor for an American company that sought to build the KRG’s security capacity. His tasks included the training of special forces and training and developing security for Erbil international airport.

Goren’s team was 90 percent Israeli: all IDF veterans with an average age of 30-40. There were “several tens” of Israelis working in Kurdistan under Goren, handpicked by him. He said that his men were the only Israelis he was aware of operating in Iraq at the time. Some had served under him in the IDF, and others were selected based on their skills, CVs, and a test Goren provided gauging their intelligence, academic abilities, loyalty and trustworthiness.

Goren used a fake identity in Kurdistan, claiming to be born of a Turkish Muslim father and Bulgarian Christian mother, and—like the rest of the Israelis in his team—never revealed himself as a Jew or Israeli. (The remaining 10 percent of his group were mainly from Britain and South Africa: They also used fake names, but acknowledged their background.) He did not bring a passport with him and held none during his stay, instead using a “special document.” In response to a question about whether clearance was specifically granted for this by KRG officials, he replied: “The people who should know that, knew that.” He chose not to reveal how he entered Kurdistan, or whether he left and returned during his time there.

“In the beginning,” he said, “it was very hard to live there. It was just after the war and the local environment was not friendly and even hostile to foreigners, so I used to be accompanied by local security guards. In all daily routines—bathing, sleeping, and so on—I was always accompanied by a gun. It was a challenge to keep my identity under cover, because a lot of military forces were there: Turkish special forces, Iranian special forces and intelligence, al-Qaeda—and they all had an eye on foreigners. But I soon started feeling like a local and driving without guards to visit markets, restaurants and the countryside. I managed to establish good connections with the locals and I was invited several times for weekend hunting trips near Suleymania, Kirkuk, Sinjar, and the Nineveh Plain. When I lived in the Christian neighborhoods, I used to visit churches on Sundays. While living in the Muslim neighborhoods, I prayed in the mosque with the Muslims because I wanted to be integrated and accepted.”

Goren stayed on military bases, in homes rented from locals, and “sometimes, because of security measures” in villages with local families. He lived alone, and his team lived in separate secured locations. They spoke only in English to one another, whether in person or on the phone. Goren speaks Turkish and Bulgarian—vindicating his identity claims—and basic Arabic.

Goren says he was not in contact with political figures in Iraq outside of the KRG, and that he had no direct contact with the IDF or the Israeli state during his time there. He confirmed that he was in contact with political figures in the KRG regarding his work, but did not disclose further information about their communications. He did not answer questions about whether he trained Kurdish security forces specifically in order to counter Iranian or Iraqi forces or whether he had any role in helping the Peshmerga secure their borders. Goren acknowledged he had been to Kirkuk and the Nineveh Plain but did not disclose the nature of his actions there, beyond stating that the security needs in those places were “not much” different than in the KRG proper.

When asked what impressed him most about the Kurdish security forces, Goren replied: “Their personal motivation. They believed in their country, they were dedicated to their goal. I was impressed by their striving for independence and desire to connect to the rest of the world.”

Goren and his team left in 2006 when “the tasks of our team within the project were finished,” a decision made by his contractors. He says he is not aware of an ongoing Israeli presence in Kurdistan, which he says is less likely following the increase in “Iranian forces and intelligence in the north” following the Iraqi parliamentary elections of 2018 and the failed referendum bid that helped lay the groundwork for that outcome.

Combating terrorism, Islamism and “extremism” were reasons I heard routinely in Israel for the necessity of support for Kurds. This appeal tapped into not merely Israel’s own particular struggles, but lines of rhetoric that attempt to unite Israel’s domestic and regional interests with global concerns. But while the KRG has had a long-standing military and political conflict with Kurdish Islamist forces, ISIS presented a different challenge—and a major opportunity for the Kurds to expand.

In Sinjar and the Nineveh Plain—the minority heartlands absorbed unilaterally into the KRG after 2003—Peshmerga told Yazidi and Assyrian residents (with occasional threat of punishment) to remain in their places, confiscated their weapons, pledged to protect them, and fled without firing a shot when ISIS attacked. The consequence of the Peshmerga’s coordinated withdrawal was genocide. At a hearing at the British Parliament I attended in March 2016, Salwa Khalaf Rasho, a 19-year-old Yazidi who was held as a sex slave by ISIS, spoke of how the Yazidis of Sinjar were forced at gunpoint by the Peshmerga to stay put as ISIS approached. Around 4,500 Yazidi men were killed; thousands of Yazidi boys abducted; and around 5,000 Yazidi women were taken into slavery. More than 60 mass graves await exhumation, and 3,000 Yazidi women and children remain in captivity.

***

Ksenia Svetlova, a member of the Knesset from the Zionist Union Party who made aliyah from Moscow at the age of 14, has led Kurdish-related efforts in the Knesset. The founder of the Kurdish-Israeli Caucus, she hosted a Knesset meeting in November 2017 aimed at bringing together Israeli MKs, lawmakers, journalists, and scholars interested in responding to the failed referendum bid in defense of the Kurds. I spoke to Svetlova in her office in the Knesset, as reporters from a Russian-language TV station circled the room, filming her for a feature.

“During my 13 years as a Middle East affairs correspondent for Channel 9,” she said, “it struck me that we know very little about other minorities—even if I’m aware that Kurds are a minority of 30 million with plenty of other minorities inside of them. I found a lot of interest in Israel among Kurds, and less anti-Semitism in comparison to Arabs. I came to the reasonable conclusion that we might benefit from this connection—as Israelis, as Jews. In 2015, I started an Israeli-Kurdish friendship lobby because I believe there isn’t enough awareness on this issue.”

In order to push back against Turkey—a major regional force—Israel often cites support for Kurdish rights, which in Turkey have been militarily expressed by the PKK, which Israel does not support—and whose leader, Abdullah Ocalan, Israel reportedly assisted in capturing. (In February 1999, security forces at the Israeli consulate in Berlin killed three Kurdish protestors who rushed the building during a protest against Israel’s reported role in the capture.) But it has expressed support for those rights exclusively through the KDP—hated rivals of the PKK—who are also supported by Turkey.

Most people I spoke to in Israel, including Svetlova, were not pleased at how easily Iraqi Kurds squandered their post-ISIS gains through the referendum. “I was a little bit surprised by the timing of the referendum, as I didn’t feel the ground was ripe for this step. It was a bold move, but it was not supported internationally. There were no guarantees, so why rock the boat?”

Svetlova is aware of the KDP betrayal of Yazidis. She is aware of the existence of the NPU—a force of local Assyrians including men from Alqosh with local, national and international legitimacy. The NPU are being prevented from full deployment in Alqosh and elsewhere in the Nineveh Plain—villages and towns with a combined Kurdish population of zero—by the Peshmerga.

“We need cooperation with the authorities in order to safeguard our holy sites,” she says, referring to the tomb of the Prophet Nahum in Alqosh. “In Kurdistan there is some flexibility: You can find out what is going on. In Arab countries, we have our sacred places blown up.”

Both Zaken and Svetlova expressed reservations about the dominance of Israeli engagement with the KRG by intelligence services. Present circumstances, however, frustrate the attempts of Israeli civilians and political actors to meaningfully expand their capacities in Kurdistan.

Israel’s regional isolation has allowed the myth of Kurdistan—both as a continuous, settled historical entity unfairly divided by colonial powers, and as an inherently moral and viable state project—to thrive. The notion that the KRG is independent in all but name, that the nonexistence of a Kurdish state is mainly a matter of recognition—not of material and political obstacles of all kinds, insurmountable in the foreseeable future—is also based on a low estimation of the viability of Iraq as a state among the Israeli political class. This belief is grounded both in the reality of Iraq’s abysmal performance as a state and the high level of self-confidence possessed by Israel.

But the hologram of Kurdistan is exempt from such analyses of fundamental state legitimacy. In that projection, the requisite first step towards fixing the problems in Iraqi Kurdistan is to cut Kurds off from Baghdad—the central authority without which the KRG could not function economically at its current spending levels—at which point the profound fissures between Kurdish groups will begin to heal and the contiguous Kurdish demographic will begin to push against current state boundaries, releasing the trapped history of Kurdistan back into the future, When the practical benefits of remaining part of Iraq are stressed, the will of the Kurds for independence is invoked.

Svetlova has been working on legislation to ring-fence the KRG from Iraq, which remains an enemy state for Israel, as a separate entity for trading and diplomatic purposes. (As Zaken put it, “It’s an insult to our Kurdish friends that we refer to a place where we are safe as an enemy state.”) Yifa Segal of the International Legal Forum, who has been working closely with Svetlova on the project, reminds me that there are international precedents: Cyprus, the Moroccan Sahara, Palestine.

“There is no Kurdistan: They aren’t an entity that you can trade with separately,” Segal explained. “But it’s not unprecedented to create a legal framework that distinguishes between a state and a particular part of it. Legally, it’s a very simple amendment to make: You just define Kurdistan in a way that it’s clear enough technically. It will open up a whole different possibility regarding trade.” It remains unclear, of course, what practical difference the legislation would make given from the KRG’s end, given that it remains part of a country that does not recognize Israel.

***

Idan Barir is a lonely voice committed to complicating the perception of Kurdish nationalism in Israel. As a result, he has been through his own strange journey with the KRG, despite having never visited Iraq. Barir has reported on the KRG in a variety of forms. His work on the subject has focused on a critique of the KRG’s political existence as a democracy and of its treatment of minorities. “Israelis have to know what their good friends are doing,” he told me as we smoked our way through the early morning in a cramped garden café in Tel Aviv, with the sawing noise of construction behind us. “You can still declare the Kurds to be your best friends, but you have to know the reality.”

After the ISIS genocide of Yazidis, Barir began to chronicle abuses, including kidnap and murder, against Yazidi civilians, activists and leaders by the KDP. His first article on these themes, “The Stepchildren of Kurdistan,” was privately translated into Kurmanji, the dialect of Kurdish predominant in KDP controlled areas, and sent to the KDP asayish, or security/intelligence forces, by researchers at the Moshe Dayan Center, a foreign-policy think tank formerly associated with the Israeli state. Following that publication, a Kurdish man named Kifah Sinjari called Barir. Barir had previously been on good terms with Sinjari, and had translated some of his articles into Hebrew. Sinjari had recently been appointed media officer for Barzani, however. He informed Barir that his “behavior had offended millions of Kurds” and he was no longer welcome in Kurdistan. Following that call, an anonymous asayish officer called Idan, and told him in Arabic that if he were to ever set foot in Erbil airport, it would be his final visit to a foreign city.

In the absence of normalized relations, Israel and Kurdistan remain free—and forced—to imagine one another according to their own vanities, fears, and desires.

“The one thing that is an axiom for Yazidis is that on Aug. 3, 2014, the Peshmerga fled in the face of ISIS. They didn’t fire one bullet to protect the Yazidis,” he said. But the pressure on Yazidis in the KRG—who are not acknowledged as a separate people, merely as a religion—to identify as Kurds and support the KDP is so great that even Yazidi representatives have been forced to counter Barir’s claims, which include information they have sent him, when they have shared a stage with him in Israel.

For many Yazidis, access to public facilities, such as schools and even hospitals, has often been conditioned on their ethnic identification as Kurds. Yazidis who do not identify as Kurds are banned from holding important positions in the local or Kurdish government. Although the great majority of Yazidis do not view themselves as Kurds, they are nonetheless always referred to as “Kurdish Yazidis” in the media.

“The KDP, and KRG in general, has often manipulated the suffering of my people in favor of their own political interests,” one member of this community told me, on the condition that he not be identified by name. “They do not recognize the specificity of the Yazidi genocide and always refer to it as a genocide against the ‘Kurds.’”

He continued, “Only a small portion, if any, of the aid sent to Yazidis through the KRG ever makes it to the Yazidi camps where thousands of displaced persons still live in harsh conditions. Kurdish security forces often prevent foreign journalists and researchers from going to Yazidi camps directly. Instead, they redirect them to Yazidi political elites close to the KDP.” He paused. “I would not be surprised if 20 years from now no Yazidis are left in Kurdistan. For the Kurdish leadership, anyone who lives in their territory is a Kurd whether they like it and embrace it or not.”

In July 2017, Svetlova hosted Nadia Murad, the Yazidi activist and ISIS genocide survivor, under a collaborative Kurdish Caucus-IsraAID banner. News of the event was widely disseminated, and eagerly greeted by Yazidis themselves, who have developed a collective admiration for Israel as a beacon of respite for the persecuted. Idan confronted Svetlova over social media following the event.

“I told her that Yazidis don’t consider themselves Kurds, and there is immense pressure on them to do so from the KDP—pressure that routinely extends to violence,” he said. “Unfortunately in Israel, these things are too often treated as small details.”

While Zaken told me that Benjamin Netanyahu is “the only leader in the world who advocated the referendum,” an examination of the prime minister’s statements last September reveals recourse to generalities and abstractions. In the absence of what Svetlova caells “a structural policy,” Israel can do little to advance Kurdish independence. Supporting the independence of Iraqi Kurdistan simply didn’t mean enough in practice, and is balanced with references to the need for Western powers to do more to help the Kurds—because Israel cannot.

The failed referendum has, for now, contracted the scope of Kurdish nationalist ambitions. But it has far from put an end to Kurdish nationalism, or its underlying bedrock: a high concentration of Kurdish demography. Despite the fact that the 30 or 40 million estimated Kurds in the Middle East have hugely varying degrees of attachment to the Kurdish identity and cause, their number and contiguity can always be invoked as a reason for a nation-state as long as the nation-state remains the dominant unit of international organization.

In the absence of normalized relations, Israel and Kurdistan remain free—and forced—to imagine one another according to their own vanities, fears, and desires. But in the KRG, Israel has so far found neither a parallel nor an outlet for its own political and democratic achievements—nor an actor capable of presently acting as a reliable geopolitical ally.

Kamal Chomani, a nonresident fellow at the Tahrir Institute for the Middle East Policy, is a prominent and articulate critic of human rights abuses and political oppression in the KRG. I spoke to Chomani to conclude with an Iraqi Kurdish perspective: He is from Erbil and now based in Hamburg.

“Israel’s support for the KRG has not led to any positive changes so far, in fact, it has had an adverse impact,” he told me. “Barzani and the KDP have used Israel’s rhetoric to further persecute Kurds, stifling political dissent and voices critical of the KRG. Israel should have approached the Kurds as a nation—and not just certain parties and families who do not have much support among the Kurdish population.”

***

You can help support Tablet’s unique brand of Jewish journalism. Click here to donate today.

Mardean Isaac is a writer and editor based in London. Educated at Cambridge and Oxford, he has written for publications including the Financial Times, Lapham’s Quarterly and New Lines magazine.