Overmatch

Iran’s increasingly sophisticated drone and missile strike packages are driving America’s beleaguered allies to seek protection in Beijing

By any objective measure, the military power of the United States continues to dwarf that of the Islamic Republic. The protests on the streets of Iran’s cities prove that the regime in Tehran is a decayed husk, deeply unpopular and beset by myriad vulnerabilities that a deft American policy could exploit. The United States has the military capabilities to prevent Iran from advancing toward a nuclear bomb and to deter it from threatening its neighbors—and it can do so without sparking a major war. It has more than enough might to reassure allies such as Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) that they can rest comfortably under the American power umbrella. What is more, the allies want to remain inside the American system. The erosion of the American order is therefore more the result of confusion in Washington than of objective shifts in global power. But how and when will that confusion cease, so that a more mutually beneficial relationship might flower?

When President Joe Biden visited Saudi Arabia in July, he sensed the existing distrust and tried to dispel it. “We will not walk away and leave a vacuum to be filled by China, Russia or Iran,” he said. But promises like this fail to reassure the allies, who are looking not for sweet words but resolute action that deters Iran. We have seen this kind of mistake in the past. In his famous speech to the National Press Club on Jan. 12, 1950, Secretary of State Dean Acheson defined America’s “defensive perimeter” in Asia in a way that omitted South Korea. A week later, Congress voted down a major assistance bill for South Korea. Six months later, the North Koreans stormed southward with the support of China and the Soviet Union, who likely concluded that the United States was unwilling to protect its ally.

In the Middle East today, the United States has once again drawn its defensive perimeter in a highly ambiguous fashion. The ambiguity has emboldened China, Russia, and Iran, and sown mistrust in the hearts of allies. The Biden administration has failed to recognize the problem and, therefore, has not begun to address it. Like marriages gone sour and houses in Malibu, international orders erode gradually at first and then all at once. News of the demise of the American order in the Middle East is certainly premature, but the ground beneath it is shifting in very unsettling ways that American policymakers appear determined to ignore.

On Jan. 17 of this year, the Houthis, Iran’s proxy in Yemen, launched an Iranian-made ballistic missile at an oil facility in the UAE near Al Dhafra Air Base, which hosts the 380th Air Expeditionary Wing of the United States Air Force. The missile failed to reach its target when the Terminal High Altitude Area Defense system (THAAD), a state-of-the-art American missile defense system, successfully intercepted it. Unmanned aerial vehicles (called UAVs or drones), which the Houthis launched simultaneously, managed to break through the defensive net, killing three people.

This attack marked the first ever use of the THAAD system in combat. One week later, on Jan. 24, the THAAD batteries were back in action, countering two Iranian-made missiles aimed directly at Al Dhafra, where approximately 2,000 American soldiers are stationed. As the missiles hurtled their way toward the Americans, THAAD and Patriot interceptors worked together to down them, narrowly averting disaster. On that day, the Houthis also simultaneously launched two ballistic missiles at Saudi Arabia. One was intercepted; the other one wounded two people.

Key elements of these attacks remain shrouded in secrecy. The Americans, the Emiratis, and the Houthis themselves have refrained from identifying some of the targeted sites. For all we know, one of the unidentified targets might have been the Burj Khalifa, the tallest building in the world which holds up to 10,000 people. These attacks could easily have generated a mass casualty event, resulting in more deaths than al-Qaida’s operations on 9/11. If the Houthis had hit Al Dhafra, the resulting loss of American life could have taken the United States into war.

Yet in what has become a clear pattern since the arrival of President Biden in office, American forces launched no militarily significant response to what, in effect, was an Iranian attack on American forces—an event that, in terms of its geopolitical impact, was every bit as important as the widely reported news that Iran is supplying the armies of Russian leader Vladimir Putin with missile and drone packages for use in the Ukraine war. In fact, the developments in the Arabian Gulf and in Ukraine are linked. Saudi Arabia and the UAE have been on the receiving end of sophisticated Iranian missiles and drones for around five years now. The immunity from counterattack that Iran has enjoyed has emboldened it to support Russia. Moreover, it has set America’s Gulf allies on a quest for security that, increasingly, is taking them out of the arms of the United States and into the waiting embrace of China. The week before last, the Saudi Foreign Ministry announced no less than three summit meetings between the Saudis, the Gulf States, and regional Arab countries with the Chinese, concurrent with the anticipated visit of China’s President Xi Jinping to the kingdom.

One person who has observed and analyzed the threat of Iran’s rapidly advancing drone and missile capabilities more closely than almost anyone is Gen. Kenneth McKenzie Jr., who retired in April as the commander of U.S. Central Command, the combatant operations command responsible for prosecuting the wars in the greater Middle East. On Oct. 6, McKenzie discussed the improved quality of Iranian weapons, emphasizing three systems in particular: ballistic missiles, cruise missiles, and drones. “Over the past five to seven years, Iranian capabilities in these three domains have risen to such a degree that they now possess what I would call effective ‘overmatch’ against their neighbors,” he said at a public event at Policy Exchange, a London think tank. “‘Overmatch,’” he explained, “is a military term that means you have the ability to attack, and your defender will not be able to mount a successful defense.”

McKenzie’s remarks were timely and candid, but they danced around the money question. Saudi Arabia and the UAE rely on the United States for their defense: If Iran possesses overmatch against them, does it also possess overmatch against the United States?

Iran’s confidence that it can threaten American forces without cost suggests that it does. “We have built power to defeat the U.S.,” said Gen. Hossein Salami the commander of the Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC), the elite branch of the Iranian armed forces, in September 2021, following an IRGC strike on a CIA hangar inside an airport complex in the northern Iraqi city of Irbil. “Today we no longer see a dangerous U.S., but we witness a failed, fleeing, and depressed U.S.,” the general continued.

Salami’s statement was not mere bluster. Iran can supply the Armed Forces of the Russian Federation with drones and missiles for the invasion of Ukraine in part because its products are worth buying, and in part because it no longer fears an American response to actions that might lead to the battlefield deaths of NATO advisers. That’s because, whether from its own territory or from Iraq, Syria, Lebanon, Yemen, or Gaza, Iran can strike the major population centers and the critical national infrastructure of every Middle Eastern country that relies on the United States for its security. The tanker traffic through the Strait of Hormuz is easy pickings, as is every American base in the Middle East.

And as America relaxes sanctions, in the hopes of luring the Iranians back into the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), as the Iran nuclear deal is officially known, the quality of Iran’s drone and missile packages threatens to take another big leap forward. A peek into the guts of the Russian-manufactured missiles that the Russian military is firing at Ukraine today offers a window onto Iran’s weapons of tomorrow. For example, the 9M727, a Russian cruise missile that routinely pounds Ukrainian targets, relies on Western components, including in its mission computer and navigation systems—which Washington has targeted through sanctions. Yet if the JCPOA is resurrected, the IRGC will go on a shopping spree. Its pockets will be filled with cash, and the top global marketplaces will open their doors wide for it. Iran’s weapons producers will integrate Western parts into their own ballistic missiles, cruise missiles, and drones, making them smarter, faster, and more maneuverable, and increasing the threat that they pose to American bases and American allies. Indeed, the battlefield in Ukraine already offers evidence that the Iranians, even while under sanctions, are improving their home-made weapons with foreign parts—with electronic components from manufacturers in Texas being found inside downed Iranian drones.

The integration of Western technology will also make Iran’s weapons much more attractive on the international arms market. Historically, Iranian weapons have suffered from a reputation for unreliability, due to imperfect reverse engineering of French, American, Chinese, and Russian designs, and near exclusive reliance on indigenous manufacturing of relatively poor quality. The lifting of American sanctions, however, will allow the IRGC to build a reliable supply chain of Western parts. The resulting standardization of Iranian products will reduce unit costs. Sales and profits will increase significantly. As Iran continues its rise as a global arms exporter, the size, sophistication, and firepower of its arsenals will also rise. Overmatch will increase.

The IRGC’s disruptive military capacity has four core components: drones, missiles, operational art, and a large network of proxy forces. If the IRGC exhibits a special creativity with respect to missiles and drones, it’s because these weapons are a good fit with the organization’s strategic culture. The IRGC has two principal missions: safeguarding the Revolution at home and spreading it abroad. As a praetorian guard tasked with protecting the regime against attacks from an intensely hostile population, the IRGC instinctively gravitates toward weapons that can be operated by a tight network of trusted loyalists without the cooperation of large numbers of politically unreliable recruits. For a group routinely tasked with carrying out terrorist attacks, the appeal of weapons that can strike terror into civilian populations is inherent.

Iran’s drone manufacturing program, one of the oldest in the Middle East, dates back to the Iran-Iraq war of the 1980s. Recent advances give Iran membership in an exclusive club—namely, those countries who produce loitering munitions, or smart “kamikaze” drones. Most of Iran’s UAVs are combat-tested, having been deployed in a long list of conflicts stretching from the Gulf to Yemen and Syria. And the list is growing, starting, most notably, with Ukraine. Of course, the Russian military has its own indigenous arsenal of unmanned aerial systems, but it uses them predominantly for surveillance, spotting for artillery, and in electronic warfare networks. By contrast, the Iranian drone program prioritizes strike assets, which operate in concert with missiles to pound targets deep inside enemy territory.

The second component of the IRGC’s disruptive military capacity is missile warfare. According to the Defense Intelligence Agency, Iran has “the largest and most diverse ballistic arsenal in the Middle East, with a substantial inventory of close-range ballistic missiles, short-range ballistic missiles, and medium-range ballistic missiles that can strike targets throughout the region up to 2,000 kilometers (1,243 miles) from Iran’s borders.” Hezbollah, Iran’s premier proxy, boasts the second largest missile arsenal in the Middle East, greater than that of either Turkey or Israel.

Size matters, of course, but so does repertoire: The missile arsenals of Iran include strategic systems suitable as delivery systems for nuclear weapons. As for their short-range inventory, it now includes road-mobile ballistic missiles fit for battlefield use and easy transmission to proxies. Among these assets, Iran’s solid-fueled missiles, centered on the Fateh-110 baseline, minimize the launch cycle, which is even more advantageous in battlefield engagements. In recent years, Iran has also made significant advancements in its development of cruise missiles.

The third component is operational art. Perhaps uniquely among global arms producers, the IRGC has traditionally held primary responsibility for missiles and drones, which it regards as inseparable components of a unified strike capacity—linking them together at every stage of their life from manufacturing to combat deployment. Iran’s missiles and drones emerge from the same industrial networks, and some weapons share critical sub-systems. The IRGC stores drones and missiles together in underground facilities and deploys them in tandem with innovative and sophisticated concepts of operations.

The final component of Iran’s disruptive military capacity is its large stable of proxy forces. The IRGC has developed a network of nonstate actors, including Hezbollah, the Houthis, and dozens of Iraqi and Syrian militias, who help Tehran counter the United States and its allies in a broad “Axis of Resistance.” The IRGC trains the proxies ideologically, giving them operational coherence and linking them to Tehran while spreading its revolutionary DNA to all corners of the Middle East. The IRGC provides Hezbollah with manufacturing skills, and the Houthis with instruction in assembling the weapons from parts. In addition, Tehran teaches its proxies distinctive concepts of operations based on integrating drones and missiles in combat. The provision of these systems and Iran’s unique way of combining them together is the key to creating a transnational terror network that can have an outsize impact on the battlefield.

When it comes to exporting the Islamic Revolution, the totemic quality of missiles, especially ballistic missiles, adds to their luster in the eyes of the IRGC. Hinting at the possession of nuclear weapons, ballistic missiles radiate power and enhance the prestige of the Islamic Republic by placing it, at least symbolically, on the same level as the United States, Russia, and China. When used asymmetrically against the United States and its allies, they serve as propaganda by action, demonstrating the power of the “Resistance Axis” and the impotence of its enemies. “I would argue that, day to day, the possession of [missile and drone] capabilities is perhaps more important to the Iranians than the nuclear [program],” Gen. McKenzie said at the London event. Iranian leaders, he continued, “have perverted their economy, and they have bent their industry to produce these weapons systems. And these are extremely effective systems.”

Indeed, since the IRGC’s intervention with Russia in Syria in 2015, the growing power and sophistication of Iran’s disruptive military capacity have become evident. The most dramatic direct IRGC attack on an American facility came on Jan. 8, 2020, in retaliation for the killing by the Trump administration of Qassem Soleimani, when the IRGC fired between 13 and 16 missiles on Al Asad base in Iraq. Though no Americans died, dozens suffered traumatic brain injuries. The United States took no offensive countermeasures in response.

The IRGC attack on Al Asad base mixed two different missiles: the solid-propellant Fateh-313 and the liquid-propellant Qiam. These missiles have very different flight trajectories and homing angles. Originally derived from a rocket baseline, the Fateh family of missiles follows a quasi-ballistic (pressed and flatter) trajectory, while the Qiam missile’s separable warhead follows a more lofted route. Even if missile defense systems had been deployed to protect the base (they were not), this mix would have complicated the job of the sensors and interceptors. The Al Asad operation demonstrated high-precision capabilities that surprised even seasoned military observers. After that attack, it is clearly wrong to depict Iran’s missiles as “area attack weapons with low accuracy,” as has been the habit of analysts for many years.

As the IRGC’s capacities have grown, the size of Iran’s missile and drone arsenals has also expanded dramatically. “Iran is fielding an increasing number of theater ballistic missiles, improving its existing inventory, and developing technical capabilities that could enable it to produce an intercontinental ballistic missile,” the U.S. Defense Intelligence Agency reported in 2019. Its drone program has shifted from building drones for intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISTAR) missions to building predominantly strike assets in industrial quantities. When going on the attack, the IRGC can now choose from pin-prick attacks to heavy bombardments; from taking direct credit for its operations to hiding behind a proxy.

The expanding sophistication and size of the IRGC’s disruptive arsenal allows Iran and its proxies to combine missiles, drones, and loitering munitions in the same “strike package”—a practice that taxes even state-of-the-art air and missile defense architectures. The combination of loitering munitions, ballistic, and cruise missiles that the Houthis launched at the UAE last January exemplifies the trend. Loitering munitions confuse sensors, especially at slower speeds, because they blend in with “ground clutter”—factors such as birds, tall buildings, and storms. In addition, swarms of loitering munitions, cheaper in unit costs, can easily saturate interceptor missiles. With their great maneuverability and low-altitude navigation skills, cruise missiles minimize their exposure to radar or avoid it altogether. Finally, ballistic missiles come in hard and fast like a bullet, carrying large warheads capable of much heavier destruction. Each one of these weapons poses its own special challenge to the sensors and interceptors of a missile defense network. When all three are combined in significant numbers, they will stress any network to a breaking point.

Iran’s disruptive military capacity has shifted the balance of power in the Gulf for two basic reasons. First, the defense economics work decidedly in Tehran’s favor. America and its allies spend more money—tens or hundreds of times more—to down Iranian missiles and drones than it costs Iran to build and launch them. Jeremy Binnie, a defense specialist at the global intelligence company Janes recently made the point in an interview with Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty with respect to the Ukraine war. While having more missiles gives Russia “the ability to sustain the bombardment against Ukraine,” the delivery of Patriot missile defense batteries will not solve the problem. “It’s eye wateringly expensive and it’s probably not really practical because each [missile] battery only covers one city,” Binnie said. “You would never get enough batteries to get the coverage you would want. You just wouldn’t be able to find them, produce them, and train enough Ukrainians.”

More importantly, when combined in a large strike package, some of Iran’s missiles and drones will inevitably break through America’s defensive shield. Even the most sophisticated defensive systems operating at peak performance cannot prevent at least some of Iran’s weapons from hitting their targets. In the January attacks against the UAE, for example, the defensive network performed well. But people still died. In missile defense, a 90% interception rate is a feat of technical wizardry. But if 1 in 10 or even 1 in 20 missiles breaks through, it’s not long before “success” starts exacting a higher cost than most leaders care to pay. Imagine if in the next attack against the UAE, one of Iran’s missiles were to slip through the defensive net and strike Burj Khalifa. “Success” will result in catastrophic failure.

Iran’s disruptive military capacity has created, in military parlance, an “offense-dominant regime” in the Middle East—a balance of power that favors Iranian offensive action. What Gen. McKenzie calls “overmatch” represents a failure by America to heed an ironclad law of military science: Defensive systems alone cannot reverse an offense-dominant regime. Offensive countermeasures are the sole means to restore the balance—through the elementary logic of deterrence.

For Iran to halt its aggression, leaders in Tehran must believe that America and allied forces will respond to provocations by exacting an unbearable cost. To be truly persuasive, American and allied forces must have at their ready sufficient firepower to respond instantaneously, and they must also demonstrate a steadfast willingness to conduct offensive operations. Such a forward-leaning strategy has long been central to Israeli military doctrine, though with some recent lapses under American political pressure. It is easy to see why Israel has long emphasized offense over defense; as a proverbial “one-bomb country,” a large percentage of whose GDP is generated within a few square miles of Tel Aviv, Israel simply cannot afford to wait to see how many bombs or missiles make it through “Iron Dome” or the latest arrays of anti-rocket laser weapons—especially if there is any chance that even one of the missiles in question might carry a “dirty bomb,” let alone a nuclear warhead. The more sophisticated Iranian systems become, the more aggressively the Israelis must lean forward in order to maintain deterrence.

By promising the integration of Israeli military systems with those of the Gulf countries, the Abraham Accords strengthened Israel’s capacity for offensive action, which according to the paradoxical logic of military strategy made it possible for Israel to adopt a somewhat more relaxed posture toward the Iranian threat. Yet the growing sophistication of the IRGC’s drone and missile packages, combined with the Biden administration’s favored strategy of “regional integration,” highlighted most recently by the U.S.-sponsored Israeli gas deal with Hezbollah, makes a more relaxed posture even less sustainable. Founded on the idea of a “balance of deterrence,” the Biden administration’s “regional integration” strategy intentionally limits the threat that Israel can pose to the IRGC and its proxies, thereby making an Iranian attack more likely—while restraining any Israeli response.

Current U.S. strategy intentionally limits the threat that Israel can pose to Iran, thereby making an Iranian attack more likely—while restraining any Israeli response.

America’s Gulf allies are even less capable of generating an offensive threat to counter Iran, as they simply do not possess the size and the military might to match the IRGC step-for-step should it decide to race up the ladder of military escalation. Iran now has one of the largest missile arsenals in the world, large enough in raw firepower to reduce the major cities of Saudi Arabia and the UAE to rubble. For the leaders in Riyadh and Abu Dhabi, the bombardments of Ukraine by Russia today and the destruction of Syrian cities by Russia and Iran in the recent past are warnings that they disregard only at their peril. If they take offensive countermeasures against Iran, residential neighborhoods in their major cities will be flattened and their critical national infrastructure destroyed. The only thing that might convince them to participate, directly or indirectly, in offensive countermeasures against Iran is an ironclad guarantee from Biden that he will deter the IRGC’s missiles and drones.

But as a matter of policy, Biden refuses to offer such a guarantee. Before retiring last April, Gen. McKenzie released the “Posture Statement” for U.S. Central Command, the unclassified annual report to Congress that every combatant commander writes, summarizing the challenges in their area of operations and the readiness of the command to meet them. Gen. McKenzie’s statement is a perfect example of its kind. The document walks the thin line between remaining faithful to orders and at the same time sounding the alarm that the orders are inadequate. About offensive counter measures, McKenzie minces no words. “Although the United States provides information and defensive assistance to Saudi and Emirati armed forces, it does not provide offensive military support,” he writes.

When nervous allies seek commitments from the United States in the form of arms sales, they meet with the same diffidence. America is happy to sell many kinds of weapons, just not the kinds that directly counterbalance Iran’s capabilities—namely, long-range missiles and drones. This refusal, too, is unlikely to be reversed, because it is based on tortuous approval processes embedded in law. Only on rare occasions has the United States delivered ballistic missiles to allies, and for years it adopted a similar restraint regarding the provision of strike drones. Although restrictions on drone exports have relaxed somewhat in recent years, streamlining the process remains difficult for several reasons—not least of which is the fact that congressional approval is mandated by law. As a result, only the president can cut through the red tape.

The chances of Biden taking such necessary action in the current political climate are slim. They grow slimmer still when considering that most of Biden’s top advisers, almost all of whom are alumni of the Obama administration, have convinced themselves that offensive countermeasures against Iran, the very bedrock of deterrence, are inherently counterproductive.

Consider Trump’s order, in January 2020, to kill Gen. Qassem Soleimani. The commander of the Quds Force of the IRGC, Soleimani was the architect of Iran’s disruptive military strategy, and the second-most powerful man in Iran. Trump gave the order specifically in order to deter Iran, to teach leaders in Tehran that operations against American forces would cost it dearly. Susan Rice, who had previously served as President Obama’s national security adviser and who now serves under Biden as his domestic policy adviser, took to the pages of The New York Times to express the prevailing view in senior Democratic circles. “Despite President Trump’s oft-professed desire to avoid war with Iran and withdraw from military entanglements in the Middle East,” she wrote at the time, “his decision to order the killing of … Iran’s second most important official … now locks our two countries in a dangerous escalatory cycle that will likely lead to wider warfare.”

In the view of senior officials in the Biden administration, offensive countermeasures against Iran will destroy the possibility of returning to the JCPOA. It will also push Iran closer to China and Russia. In his bid for the presidency in 2020, Biden campaigned on the idea that diplomatic engagement with Iran was, to quote an op-ed published under his name, “a smarter way” to contain the IRGC’s proxy network and to prevent it from developing a nuclear weapon. A decision by Biden to adopt offensive countermeasures against Iran would place him on a collision course with the left-wing of his base.

Locked in a maze of bad ideas and domestic political considerations, the Biden administration cannot be expected to remedy the situation that allowed Iran to possess overmatch against the United States and its allies in the Middle East. The resulting damage to American alliances is significant.

Nothing demoralizes Saudi, Emirati, and Israeli leaders more than the spectacle of American forces steadfastly refusing to defend themselves. Consider the background to the twin attacks on the UAE and Saudi Arabia last January. For several years prior to the attack, Iran had provided the Houthi forces with drones, ballistic missiles, cruise missiles, loitering munitions, coastal weapons, and related technologies. In the words of Gen. McKenzie’s Posture Statement, the provision of these capabilities to the Houthis constituted “the most complex and consequential threat to U.S., partner, and allied forces.” The Iranian officer who was—and still remains—in charge on the ground in Yemen is Abdul Reza Shahlai, a man responsible for the deaths of more Americans than perhaps any other living person. A deputy commander of the IRGC Quds Force, and a close associate of Qassem Solemani, Shahlai had extensive experience in Iraq, where he was in charge, among other things, of organizing attacks on American forces. In 2011, he played a major organizing role in the plot to assassinate Adel al-Jubeir, the Saudi ambassador to the United States, at a restaurant in Washington, D.C.

Under the guidance of Shahlai and emboldened by declining American support for the Saudi-led coalition in Yemen, the Houthis conducted over 325 cross-border attacks with drones and missiles in the year prior to the attack on Al Dhafra. Some significant number of these attacks endangered U.S. citizens and military personnel. During the same period, Iranian proxies in Iraq directly attacked American forces dozens of times.

After the Jan. 24 ballistic missile attack on American forces, U.S. National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan met with the Saudi and Emirati ambassadors to the United States. According to the official summary of the meeting, the three did not discuss the Iranian ballistic missile attack on American forces but rather “the ongoing Houthi attacks against civilian targets in the UAE and Saudi Arabia that have resulted in civilian casualties in both countries.” In other words, Sullivan publicly framed the attacks as part of a bilateral contest over Yemen between Saudi Arabia and the UAE on the one hand, and the Houthis on the other—erasing entirely the Iranian role in the attacks. That’s because any public acknowledgement of Tehran’s decisive role would inevitably open the Biden administration to questions about how it plans to counter Iran. These are inconvenient questions, because the administration has no such plan, and no intention of developing one.

If the Americans won’t even defend themselves, the Emiratis and Saudis wonder, why would they ever defend us? Yet there is one thing that the Biden administration is clearly hardwired to defend: the JCPOA. For nearly two years, the administration has presented the resurrection of the nuclear deal as an essential first step to solving all problems related to Iran. A return to the JCPOA, however, will not reduce the deterrence gap created by Iran’s disruptive military capacity. It will only widen it.

To grasp why, consider the Noor anti-ship missile, which Hezbollah used against Israel in 2006 to cripple the INS Hanit, the Israeli Navy’s Sa’ar 5-class corvette. At the time, Israel was not aware that Hezbollah possessed a weapon of this range. The Hanit limped to port, and was removed from combat for the duration of the war.

How did the Iranians acquire this technology? Explanations differ, but they probably reverse-engineered a Chinese missile, the C-802, which is China’s analogue to France’s famous Exocet missile. To compare the Exocet to the Noor, however, is like comparing an original photograph to a blurry photocopy of a photocopy of that photograph. In other words, Hezbollah disabled a state-of-the-art warship with an imperfect reproduction of a Western system that was three decades old. If the JCPOA is revived, Iran will turn to Western suppliers to modernize its homegrown defense industries. The IRGC’s procurement network will be able to purchase off-the-shelf subsystems of missiles and drones, such as aerial engines, guidance and navigation systems, advanced sensors, mission computers, command and control data link systems, and more. The improvement that these items will make to existing systems will allow Iranian missiles and drones to advance quickly, skipping a generation or two in a few short years. What is more, Iran will make these advances while relying on lessons learned from hot conflicts in both the Middle East and Ukraine—the professional assessment of a real combat record being the most precious type of input for defense industries seeking to improve their products.

These predictions hardly require a crystal ball. Even while under severe sanctions, Iran has already become an arms exporter, and not just to Hezbollah, the Houthis, and other members of the “Resistance Axis.” In addition to Russia, Tehran has supplied drones to Ethiopia and Venezuela, and it is building a drone factory in Tajikistan. It is reportedly exploring weapons deals with Armenia, Serbia, and Algeria, among others. The list of prospects will undoubtedly increase as the world sees the effectiveness of Iranian drones and missiles in Ukraine. If today Venezuela were to import the Soumar, an Iranian long-range cruise missile based on the Soviet-Russian Kh-55 line of missiles, it would probably have difficulty hitting targets inside the United States. Its range will increase, however, once the JCPOA facilitates the integration of Western components. Cities such as Miami and New Orleans will easily fall into the crosshairs of the anti-American regime in Caracas, posing a direct strategic threat to the American homeland.

But suppose the JCPOA is never resurrected. Suppose Iran remains under harsh American sanctions. Unfortunately, Iran’s disruptive military capacity will still rise, because it has already reached a critical mass, meaning it will continue to grow under even the harshest sanctions regime. The evidence for this is in front of our eyes, in the form of the Russian military’s need for a large-scale supply of Iranian weapons to sustain its campaign in Ukraine. The IRGC’s defense industrial network can now supply the world’s second-largest arms exporter in a high-tempo invasion at NATO’s doorstep. As a critical supplier to Russia, Iran will enjoy Moscow’s backing as it works to develop its weapons. In the eyes of the Kremlin, Tehran is not merely a strategic partner in the Middle East; it is a critical arms supplier that came to Putin’s aid in his hour of need. From now on, Russia will do all it can to ensure that the Iranian drones and missiles keep coming. In short, there is no turning back from here.

With or without the JCPOA, Iran’s drone and missile programs will grow, although they will expand much faster under a revived nuclear deal. From the point of view of the leaders in Riyadh and Abu Dhabi, therefore, Iranian overmatch is, in effect, a permanent aspect of life.

The IRGC’s defense industrial network can now supply the world’s second-largest arms exporter in a high-tempo invasion at NATO’s doorstep.

The reality of Iranian overmatch is now driving a dizzying number of diplomatic shifts in the Middle East. Over the last year alone, the UAE has, among other moves, ended a decadelong bitter rivalry with Turkey, improved relations with Israel and Iran simultaneously, and opened up to the Assad regime. These should be understood, simultaneously, as moves toward Iran and its ally Assad in order to gain goodwill in Tehran (not to mention Washington, where the Biden administration looks favorably on the diplomatic engagement of the Islamic Republic) while simultaneously developing relationships with the two regional powers, Israel and Turkey, who, each in its own way, are capable of counterbalancing Iranian power. The goal is to reduce the Iranian threat as much as possible while also increasing the number of friends who can help manage it.

All this activity has taken place against the backdrop of increasingly close UAE ties with China. In the spring of 2021, U.S. intelligence agencies learned, according to The Wall Street Journal, that China was secretly building what they suspected was a military facility in the UAE. Of all the forms of hedging by America’s Gulf allies, the hedging toward Beijing is the one that should alarm Washington the most.

The UAE is located on the south coast of the Strait of Hormuz, through which around one-third of the world’s liquefied natural gas and one quarter of its oil passes. After some arm twisting from Washington, the Emiratis shut down China’s military construction project. Had it reached completion, the facility would have become China’s second base overlooking a Middle Eastern choke point, the first being the Chinese People’s Liberation Army Support Base in Djibouti. Though technically in Africa, the Djibouti base lies just 20 miles from Yemen. It watches over the Bab al-Mandab Strait, which guards the Red Sea approaches to the Suez Canal from the Indian Ocean, and through which most of the oil that Gulf countries export to Europe passes—about 3.6 million barrels per day. About 2.6 million barrels per day flow through it in the opposite direction, mainly to Asian markets, including China, from European and African producers.

America’s greatest rival since the Soviet Union is maneuvering to bring the global tanker trade within range, and it takes little imagination to understand why. China and its East Asian rivals are all heavily dependent on oil and liquefied natural gas that either originates in the Middle East or transits through it. If Xi Jinping were to launch an invasion of Taiwan, Washington could impose an energy blockade on China. This option is one of America’s greatest instruments for deterring an attack. Acutely aware of this vulnerability, Xi aspires to supplant the United States as the dominant power in the Middle East. By achieving this goal, Beijing would simultaneously secure China’s supply lines while placing its thumb on the windpipe of its rivals, including Taiwan.

Those analysts who insist that China is not seeking to supplant the United States in the Middle East rest their argument on the claim that China’s interests in the region are overwhelmingly commercial. If Beijing were to involve itself in security matters, so the argument goes, it would have to take sides in bitter disputes, such as those between Iran and its antagonists. Instead, Beijing seeks good relations with all sides, so that it will not be shut out of any market and be free to buy and sell from all. In addition, the analysts note that Beijing does not have the alliance musculature to provide credible security guarantees and to back them up with continuous delivery of reliable weaponry. Beijing simply cannot offer America’s allies what they want most—namely, protection from Iran. Only the United States can provide the necessary security umbrella.

These points are not so much false as overstated. China’s naval buildup is the fastest the world has ever seen. Within about a decade, the Chinese navy will have an expeditionary force capable of intervening in all corners of the world. While Beijing does not yet have the power to snatch away America’s allies in one fell swoop, it is racing toward acquiring that power—aided by American policymakers in Washington, who are depriving U.S. allies of their ability to meet the Iranian threat to their own countries.

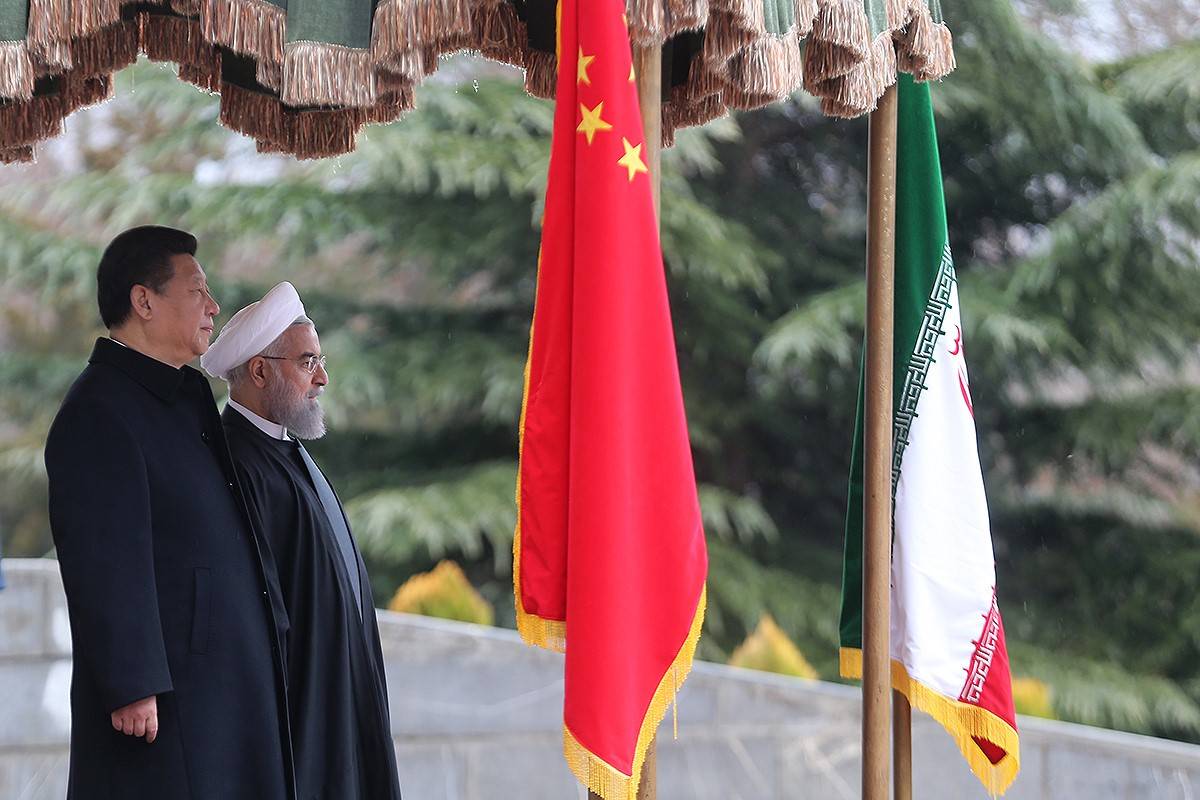

American analysts inside and outside government paid scant attention to Xi’s change of course in 2016, when competition with the United States in the Middle East took an overtly military turn. This was the year that Xi first decided to build the base in Djibouti. In January of that year, he visited the region, stopping in Saudi Arabia, Egypt, and Iran, which received special attention. While in Tehran, he and his hosts drafted a 25-year “Comprehensive Strategic Partnership,” which was finalized five years later, in 2021. The exact details of the agreement are still unknown, but credible reporting indicates that China has pledged to invest $400 billion in exchange for a discounted supply of oil. The two powers will also increase their cooperation in security and defense, including in weapons development. Subsequently, China also initiated the accession process for Iran’s full membership in the Shanghai Cooperation Organization, a process that came to fruition in September.

China’s courtship of Iran did not, as one might have expected, alienate Riyadh and Abu Dhabi. On the contrary, it sparked a competition for influence in Beijing—one that Xi is happy to stoke. On the eve of his trip, the Chinese government also published an “Arab Policy Paper,” which, among things, promised to “deepen cooperation on weapons, equipment and various specialized technologies.” The PRC advanced its status as an arms supplier to the region, providing military equipment to Saudi Arabia and the UAE, among others, at discount prices and without preconditions, attempting, according to Gen. McKenzie’s Posture Statement, “to supplant the U.S. as ‘a partner of choice.’” As a result, China increased its arms sales to Saudi Arabia and the UAE by 386% and 169%, respectively, over the preceding four-year period.

The specific weapons that the UAE and Saudi Arabia are buying speak volumes. Abu Dhabi and Riyadh are both buying drones from China. In 2016, China and Saudi Arabia closed a deal to establish a joint drone production plant in the kingdom. With necessary reexport licensing, this plant can also turn Saudi Arabia into a commercial hub for selling Chinese drones to Middle Eastern clientele. Beijing is not just providing drones to America’s closest and most influential Arab ally—it is turning Riyadh into a supplier of Chinese technology to America’s other Middle Eastern friends. In addition to drones, Riyadh is purchasing ballistic missiles (while also receiving assistance on its nuclear program). In the early 1990s, Riyadh purchased surface-to-surface ballistic missiles from China, which can carry nuclear warheads up to 3,000 kilometers. In 2007, however, the Saudis procured more accurate missiles with a much shorter range. Why the shift? Riyadh was closely tracking the development of Iran’s arsenal and acquiring systems designed to match it.

Xi has managed to insinuate China into the balance of power between America’s Gulf allies and Iran.

That Saudi Arabia and the UAE spend 10 or 20 times more money on American than Chinese weapons gives comfort to the American analysts who see little strategic calculus behind Beijing’s military sales. The huge investment in American arms and equipment proves to them that China poses no threat. But a dollar-for-dollar comparison ignores this strategically important fact: China now holds the balance between Iran and the Gulf States with respect to the very weapons that give Iran its disruptive military edge. Xi Jinping has managed to insinuate China into the balance of power between America’s Gulf allies and Iran.

The significance of this fact increases when considering an additional advantage that, in the eyes of America’s allies, China holds over the United States. Beijing, unlike Washington, actually wields influence in Tehran—in fact, it is the only power that does. Therefore, it is not entirely true to say that only the United States has the tools to help its allies contain Iran. Washington has unparalleled military tools, to be sure, but it pointedly refuses to use them. China, by contrast, has political influence, and it is working toward developing the military tools it needs to achieve its strategic goals.

Especially after the withdrawal from Afghanistan, America’s allies believe that the United States is likely to leave the Middle East. China, by contrast, is screaming with a bullhorn that it will soon be a major player in the region. The arms purchases of Abu Dhabi and Riyadh are but one part of a hedge toward the rising power. Take, for example, the case of the UAE. In addition to buying Chinese weapons, Abu Dhabi also works with Chinese companies in areas that might be called “defense adjacent,” such as artificial intelligence, space exploration, and telecommunications. Complacent American analysts code this cooperation as “commercial” activity, but it comes loaded with adverse strategic implications for the United States.

The controversy over the UAE’s efforts to buy the F-35 Joint Strike Fighter demonstrates the magnitude of the problem. When the Emiratis refused to renege on their deal with Huawei to build their 5G telecoms infrastructure, the United States refused to follow through on its commitment to sell them the F-35, which is the backbone of fifth-generation tactical military aviation. The UAE would have become the only Arab nation to gain admission into the F-35 club. The lost revenues to America totaled, in upfront costs alone, $23 billion. The UAE has been effectively downgraded as an American defense partner, perhaps permanently.

Using relatively small arms sales and commercial transactions, the Chinese president has already slipped the thin end of a very big wedge between the United States and its Gulf allies. If America doesn’t reverse its course soon, the gap that Xi has created by leveraging the Iranian threat will continue to widen, empowering China and leaving America out in the cold.

Michael Doran is Director of the Center for Peace and Security in the Middle East and a Senior Fellow at the Hudson Institute in Washington, D.C.

Can Kasapoğlu is a nonresident senior fellow at the Hudson Institute.