Premiership

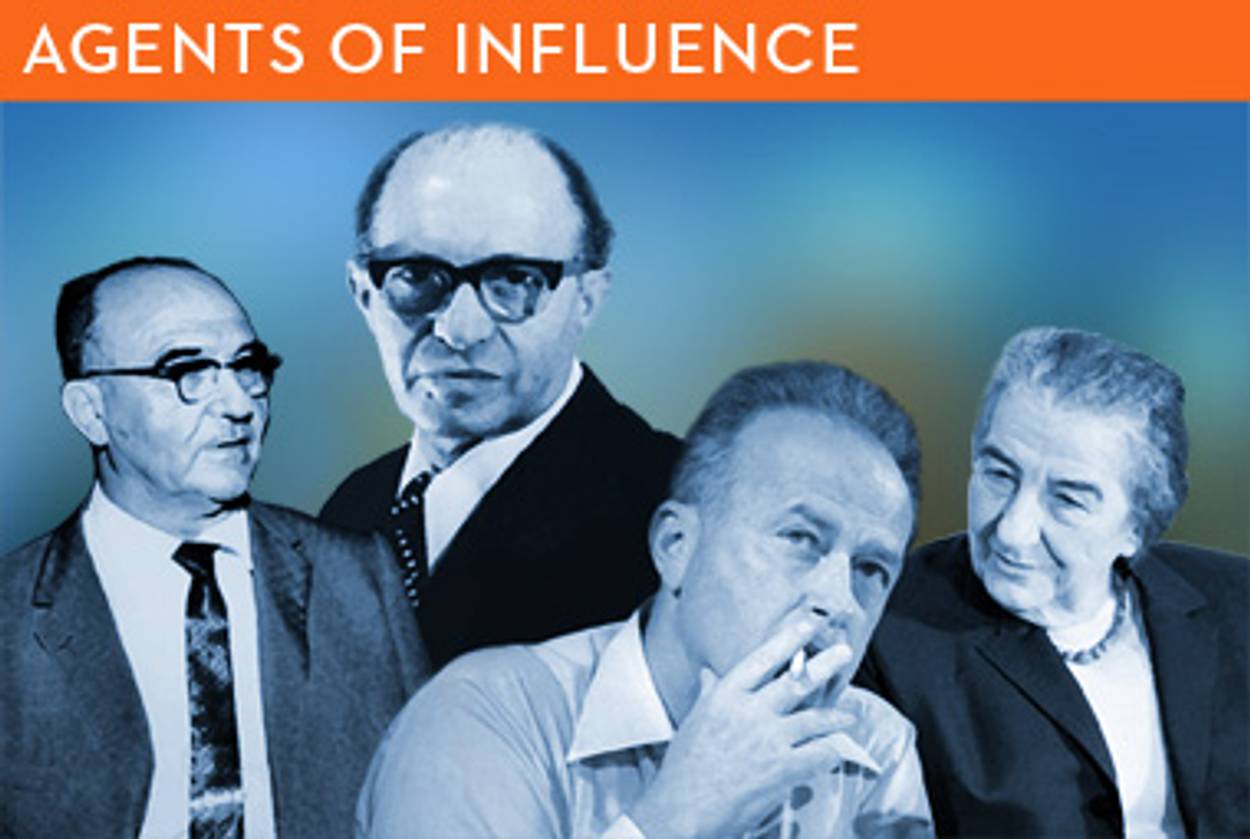

A new book gives an insider’s assessment of four Israeli prime ministers—and Menachem Begin the voice he never had

Yehuda Avner is a British-born Israeli diplomat who spent many years in the prime minister’s office, where he worked as speechwriter, adviser, and private confidant for Levi Eshkol, Yitzhak Rabin, Golda Meir, and Menachem Begin. As it turns out, he was also keeping notes. “In very many of these meetings I was the note-taker, employing my own invented shorthand which I would then transcribe for the official record,” Avner told me on the phone from Jerusalem earlier this week. “However, I never threw away those scribbles. I confess I was naughty. Not that I ever contemplated I would one day use them.”

Now the career diplomat has turned his surreptitious scribbles into a 700-page narrative, The Prime Ministers: An Intimate Narrative of Israeli Leadership, that he explains “is not history, but a story about history.” His insider’s account of the founding and building of the state of Israel is also a memoir of sorts, peculiar in that the memoirist gives all the best lines away to others. “Of course, I have my feelings, philosophies, ideas about things,” said the 81-year-old Avner, “but the book is not about me. My intent was to bring back to life episodes showing how these figures behaved, primarily under situations of stress, and also some unforgettable intimate moments.”

But The Prime Ministers is also a sobering post-Oslo account of pre-Oslo Israeli leadership. With the conclusion of the Cold War, U.S. presidents could afford to entertain fantasies of a new world order and a peace dividend, but not Israel. In many ways, Jerusalem forgot how to make its case to Washington, that it was not merely a chip in a game of geopolitical poker, but a strategic asset in its own right—and had been recognized as such even by a U.S. president, Richard M. Nixon, who seemingly had no love for the Jews. It was Begin who clearly explained that the Jews had rights, not merely claims, to their historical homeland. Avner’s book is a timely reminder that Israel has not survived these last 60-plus years because it has satisfied the claims of the world community, but has rather thrived thanks to the ingenuity, inspiration, and courage of its leaders.

The major figures here are the four prime ministers for whom Avner worked, with Begin as the book’s undisputed protagonist, often stealing scenes from the other three even when they are the sitting prime minister and Begin is the leader of the opposition. In this telling, Begin towers over them all, an Israeli leader, Avner writes, “possessed of a unique, all-encompassing sense of Jewish history.”

While the election of the right-wing Begin government moved mainstream Israeli politics to the center (in the same way that Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher affected the United States and the United Kingdom), Rabin forged a strategic relationship with the United States. These two more than any of the country’s other famous patriarchs are the founders of current-day Israel.

Rabin’s influence came in part from his direct involvement in domestic U.S. politics beginning with his support of Richard Nixon against Hubert Humphrey in the 1968 presidential election. As Avner writes, Rabin explained his tactical style to a somewhat astonished Begin:

It is not enough for an Israeli ambassador here to simply say “I’m pursuing my country’s best interests according to the book.” To promote our interests an Israeli ambassador has to take advantage of the rivalries between the Democrats and Republicans. An Israeli ambassador who is either unwilling or unable to maneuver his way through the complex American political landscape to promote Israel’s strategic interests would do well to pack his bags and go home.

I asked Avner, the former ambassador to the United Kingdom and Australia, if he thought this sort of direct involvement should be part of the Israeli ambassador to Washington’s job description. Not at all, Avner insisted. “It could only happen by default, if one wins trust and is invited into the inner sanctums of power. But you can’t set out to do it. And I don’t know of anyone else before or after Rabin who had the chutzpah to say it this way as he did.” Rabin was special. “He was the right man there, winning the trust of the Nixon Administration and not least Kissinger himself. He once said the only secretary of state who truly understood the Israel-Arab conflict in all its complexities was Henry Kissinger. Nevertheless, for much of the time, they had a love-hate relationship with each other.”

***

Avner’s book is something of an anomaly among political memoirs, where mid-level bureaucrats typically assert a centrality for themselves that rarely survives book reviews, never mind the first draft of history. Avner on the other hand is a major player, “one of that same impressive generation of British-born Israelis who made their mark in serving the State of Israel, like Efraim Halevy and the late David Kimche,” said Jonathan Spyer, a British-born Middle East analyst who moved to Israel 20 years ago. Nonetheless, Avner’s own account of his career invariably forces him to the margins, which becomes the book’s source of self-effacing humor.

Avner writes, for instance, of how Eshkol once stopped in the middle of delivering a speech Avner had written to disapprove of a passage and chastise Avner in front of the audience. On another occasion, at a White House banquet, Avner’s lavish kosher meal created such a stir with his table companions that across the room President Gerald Ford wondered what was going on. It was Avner’s birthday, explained Prime Minister Rabin. Accordingly, the U.S. commander-in-chief led the entire banquet hall in a chorus of “Happy birthday, Yeduha,” unaware that Avner’s name had been misspelled on his place card. Afterward, Rabin explained to Avner that he had no choice but to fabricate the story about his birthday. Otherwise, he tells him, “there’d be a headline in the newspapers that you ate kosher and I didn’t, and the religious parties will bolt the coalition, and I’ll have a government crisis on my hands.” Justice is served when Betty Ford drags Rabin out on to dance floor, where he nearly trips over his own shoelaces, only to be saved by the comparatively light-footed Henry Kissinger.

The book’s much more significant duet is Kissinger and Rabin’s, which helped consolidate the alliance between Washington and Jerusalem. Eshkol named Rabin ambassador to the United States in 1969, and Avner followed him there, marveling at this future prime minister’s access to the White House.

“Rabin was central to the U.S.-Israel relationship, especially within the Cold War context,” said Avner. Rabin understood that the Nixon White House’s chief concern was the Soviet Union and made the case for Israel as a strategic asset primed to take on Moscow’s regional allies, Egypt, and Syria. He also teamed up with Kissinger in an intra-Beltway battle against Nixon’s less than Israel-friendly Secretary of State, William Rogers.

As in most portraits, Kissinger comes off as a complicated character, best understood, in Avner’s reckoning, in light of two of Kissinger’s German precursors, Metternich, the 19th-century statesman and strategist, and Heinz, a teenage refugee from Nazi Germany who wound up at George Washington High School in upper Manhattan—that is, the adolescent Kissinger.

Avner relates a remarkable story of sitting at the King David hotel in Jerusalem with a Washington psychiatrist whom Avner pseudonymously refers to as Willie Fort. As Kissinger makes his way through the lobby, Fort hails him—“Heinz, Heinz”—and Kissinger’s face turns flush, before he moves on, ignoring Fort. Avner demands an explanation for the strange scene, and his companion relates how he and Kissinger were close friends in high school, both of them refugees from Hitler’s Germany. Avner writes:

Henry Kissinger, [Fort] said, habitually insisted he had no lasting memories of his childhood persecutions in Germany. This was nonsense! In 1938, when Jews were being beaten and murdered in the streets, and his family had to flee for their lives he was at the most impressionable age of 15. At that age he would have remembered everything: his feelings of insecurity, the trauma of being expelled, of not being accepted; what it meant to lose control of one’s life, to be powerless, to see one’s beloved heroes suddenly helpless, overtaken by the brutal events, most notably his father whom he greatly admired. Those demons would never leave Henry Kissinger however hard he tried to drown them in self-delusion.

How, Avner asks Fort, does this impact his role as mediator between us and the Arabs?

“ ‘People like him invariably over-compensate,’ ” Avner quotes Fort. “ ‘They go to great lengths to subdue whatever emotional bias they might feel, and lean over backwards in favor of the other side to prove they are being even-handed and objective.’ ”

***

For Avner, at the opposite end of the spectrum from Kissinger is Begin, who would do anything for his own people. “He was a quintessential Jew,” said Avner, who, as he explains, had not been a Begin supporter until then. “For years the word ‘terrorist’ clung to him,” Avner told me, “and when he was elected in 1977 he was described in many a corridor of power as a ‘warmonger.’ Nevertheless, it was he who won the Nobel Peace Prize for negotiating the peace with Egypt. Upon election he asked me to stay on working with him as an adviser, and I was hesitant at first. I asked him for time to think it over, and he said, ‘You want to speak to Rabin don’t you?’ Yes, I told him. So I called Rabin and he said, ‘Take the job, Begin is an honest and responsible man. He’s your kind of Jew, observant.’ Before Begin, all of Israel’s leaders were diehard socialists. It was unheard of before him, for example, that a dinner at the White House would be kosher. After him, all White House dinners for visiting Israeli prime ministers are kosher.”

Avner stayed on to “shakespearize,” as Begin said, the prime minister’s Polish English, but the most important piece of writing Avner may have done on Begin’s behalf is this book. In the afterword, Avner recalls explaining to Margaret Thatcher that Begin never produced his own memoirs. Accordingly, Begin is the presiding spirit of The Prime Ministers, which opens with Avner’s first recollection as a boy of hearing English neighbors cursing the name of the Irgun leader, and concludes with Begin’s death in 1992.

“What opened my heart was the man himself,” Avner said. “His nobility stretched into the small things. I was recently telling Natan Sharansky something about Begin, which he didn’t know and which brought tears to his eyes. When Sharansky was imprisoned in the Soviet Union, his wife, Avital, received a government stipend to make phone calls to Moscow each week to keep the campaign for his freedom alive, but some bureaucrat told her she was overstepping her budget. When Begin heard about this, he instructed that all of these bills should come to him, and he would pay for them out of his own pocket.”

I asked Avner where Begin’s reputation stands today. “In all the polls for the last few years, Begin has overtaken Ben Gurion. Why? Overwhelmingly, people ascribe to his credit the peace treaty with Egypt. He is also fondly remembered for his humble and chivalrous lifestyle. He is particularly revered by the Sephardic Jews who gave him his majority in 1977. In fact it was Begin who emancipated them into the democratic system, virtually all of them having come from lands—North Africa and the Middle East—where democracy is an eccentricity. He was the first to appoint a swath of Sephardic Jews to his cabinet. Moreover, Begin is the man credited for having prevented two civil wars,” said Avner, referring to the sinking of the Altalena in 1948 and before that when Begin and Ben Gurion squared off against each other in 1944. “Begin believed that a Jew must never raise a finger against another Jew. He was haunted by the Holocaust and lived Jewry’s ancient past when Jerusalem fell to the Romans in 70 CE because Jews were fighting each other. He was so steeped in Jewish history, he talked about the destruction of the temple as if it had happened yesterday.”

And what, I asked Avner, would Begin make of Israel’s strategic situation today? After all, against the good opinion of the international community, including Washington, Begin ordered the destruction of Iraq’s nuclear facility at Osirak. Would he do the same thing with Iran?

“I don’t know. He would have opposed sanctions from the start,” said Avner, believing that Begin would have had no faith in their efficacy against an ideologically driven regime like Iran. “At the same time,” Avner continued, “Begin, having himself once commanded a force of his own—the Irgun during the British mandate—knew the limits of military power, and I don’t know if he would have thought that Israel had the power by itself to defang Iran. But as obsessed as he was with the Holocaust, he would have mounted a vociferous worldwide campaign against the Iranian leaders who deny the Holocaust and threaten to wipe the Jewish state off the map. I don’t think our present leaders—and the Diaspora Jewish leadership for that matter—are doing enough to alert the world of the existential dangers for the whole of the West, and not only Israel. Begin would be shouting from the rooftops demanding that this be put at the very top of the international agenda. For all the talk it is still not at the top of the international agenda. One thing is clear: Given our geopolitical situation, Israel simply cannot tolerate a nuclear Iran.”

Lee Smith is the author of The Consequences of Syria.

Lee Smith is the author of The Permanent Coup: How Enemies Foreign and Domestic Targeted the American President (2020).