The Sentimental Antisemite

The CIA’s case for Palestinian statehood was based on analysis. Then the analysts turned out to be wrong.

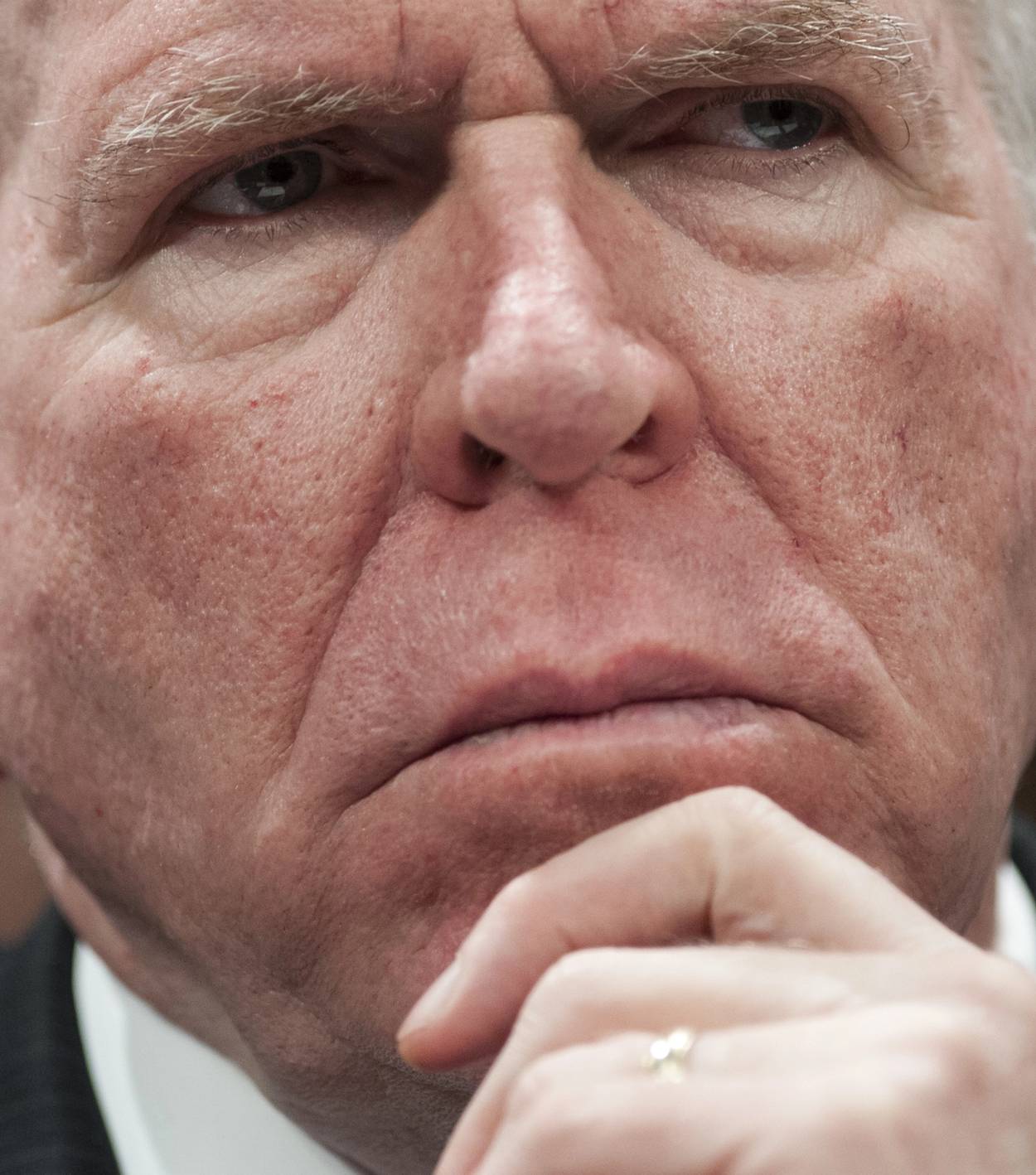

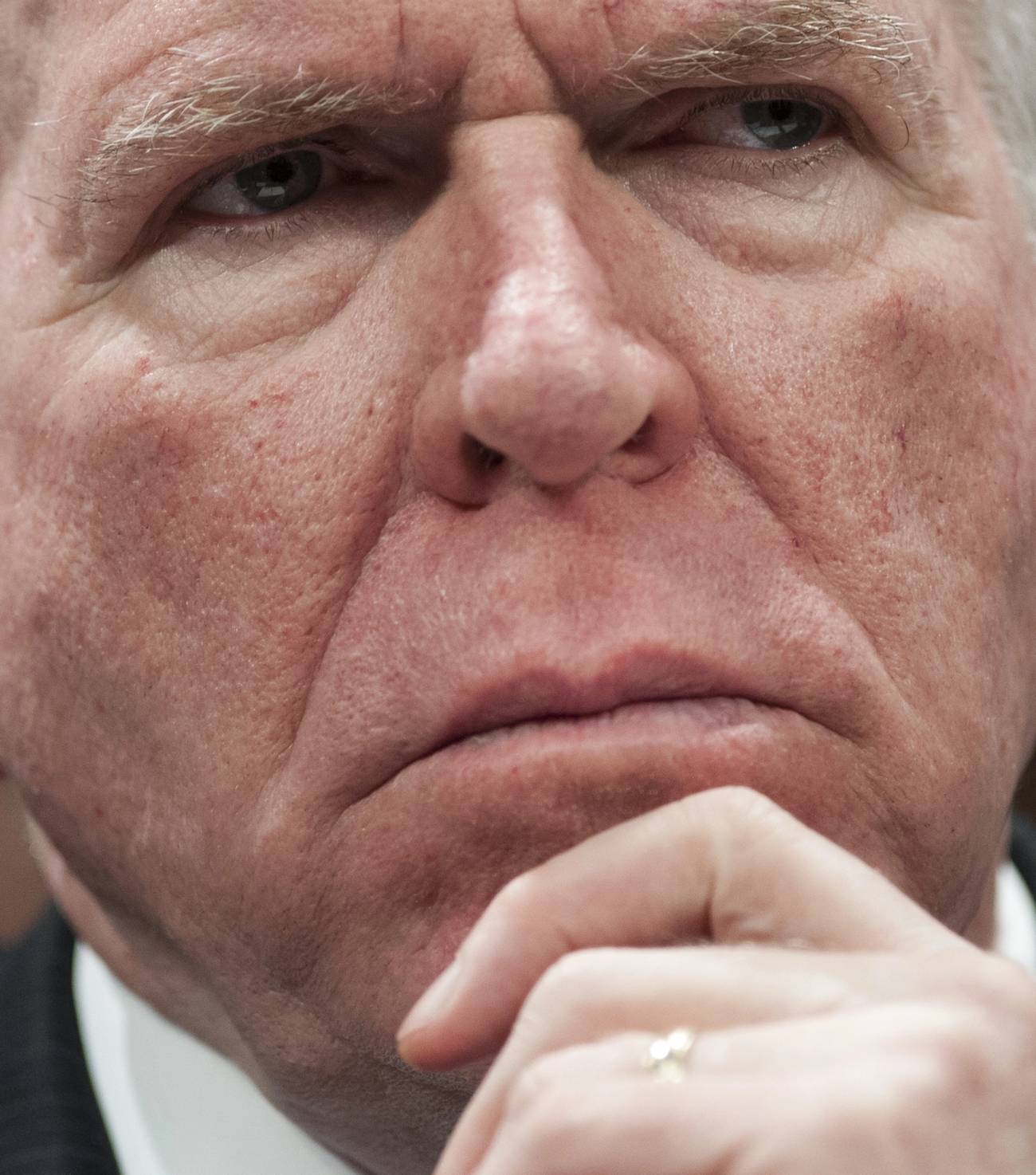

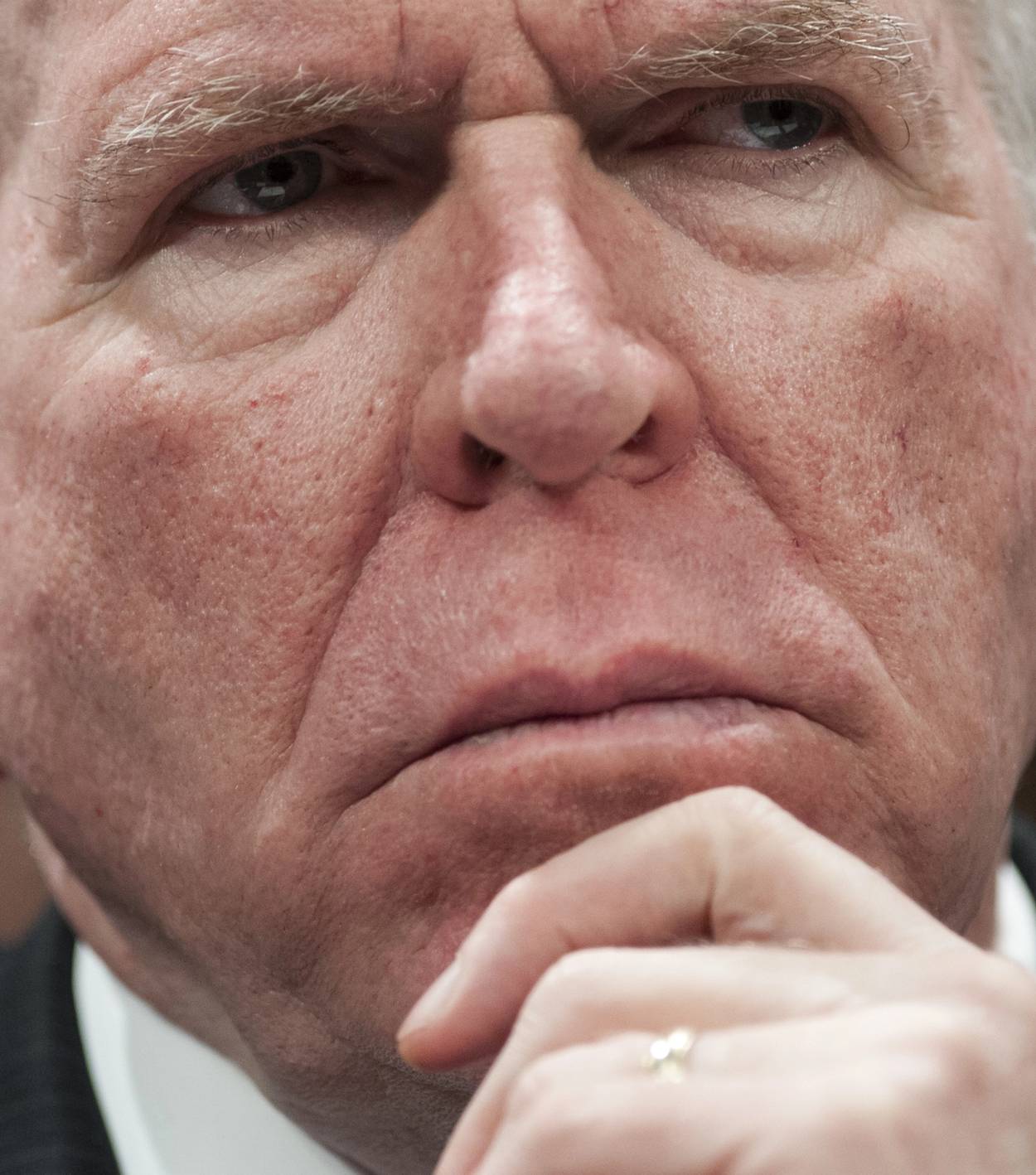

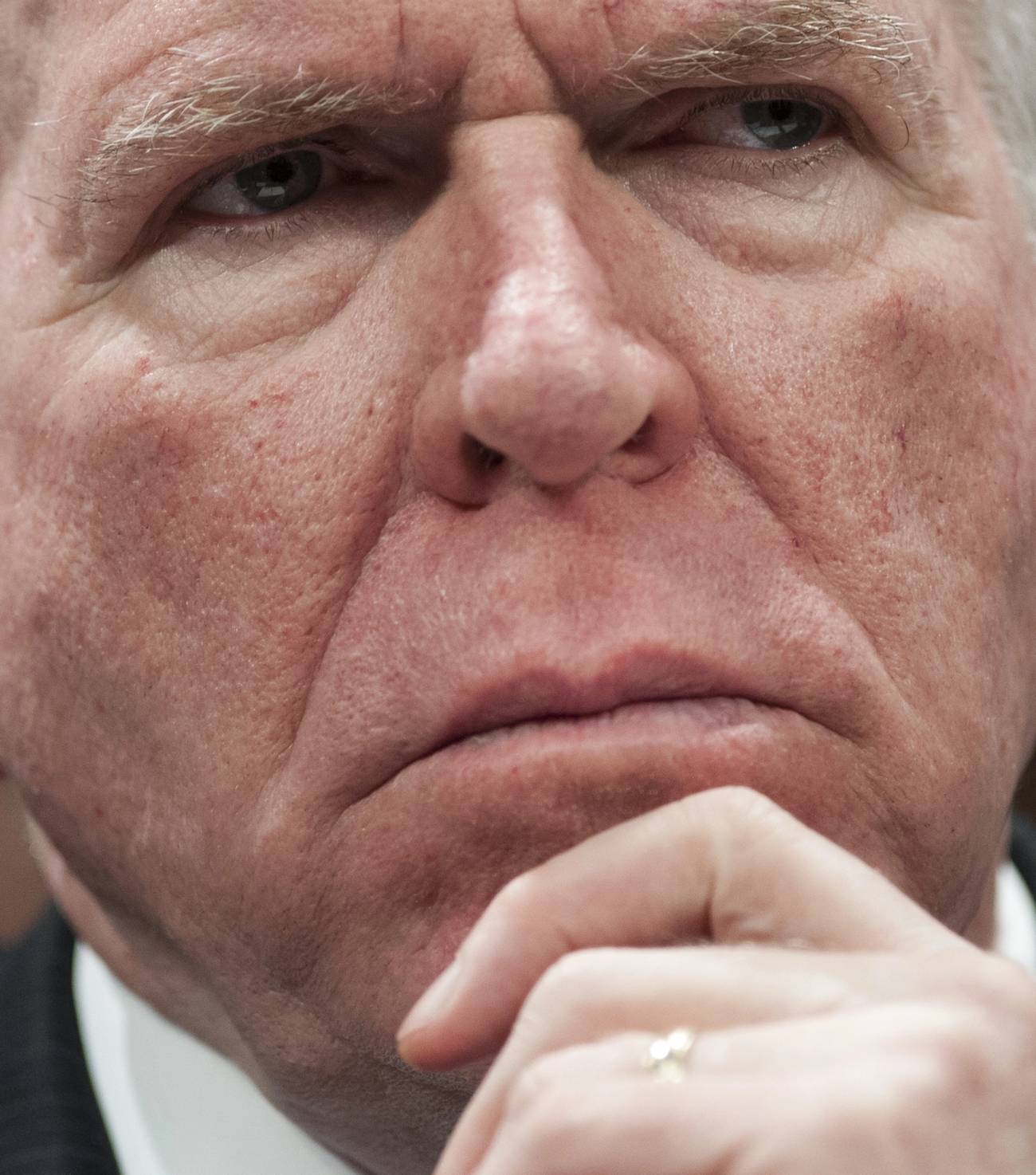

It’s not hard to see the dilemma facing John Brennan, the former director of the Central Intelligence Agency. Decades of U.S. intelligence assessments of the Middle East, including many he composed and greenlit himself, were trashed during the past four years, as Donald Trump crossed virtually every red line previously drawn by the CIA and other U.S. spy services. Even pro-Israel organizations had assumed that it doesn’t matter what presidential candidates say on the stump—like Bill Clinton, like George W. Bush, and like Barack Obama, they all inevitably walk back their campaign promises. Sure, all presidents would like to recognize Jerusalem as Israel’s capital. But after seeing the top-secret intelligence and consulting with their well-connected spy chiefs, what president would risk the war that such a move would start?

But the so-called Arab street didn’t erupt when Trump moved the U.S. Embassy to Jerusalem. Islamists didn’t topple the regimes in Cairo and Amman when the U.S. recognized Israel’s sovereignty in the Golan Heights. Saudi Arabia, the custodian of the two holy shrines in Mecca and Medina, gave all but explicit approval when the United Arab Emirates and Bahrain normalized relations with Israel.

That left Brennan with egg on his face. Now out of government, Brennan believes that despite “dealing with a dizzying array of domestic and international problems,” the Biden administration should prioritize “the Palestinian quest for statehood.” Why? To put an end to Israel’s “oppressive security practices,” Brennan wrote on Tuesday for The New York Times. But the case he makes for bumping Palestinian nationalism to the top of the White House’s to-do list is not strategic or rational. It’s sentimental, with a dollop of antisemitism on top—just like his decades of poor intelligence assessments.

“I always found it difficult to fathom how a nation of people deeply scarred by a history replete with prejudice, religious persecution, & unspeakable violence perpetrated against them would not be the empathetic champions of those whose rights & freedoms are still abridged,” Brennan tweeted Tuesday, promoting his Times op-ed.

Really? It is quite easy, in fact, to imagine the responses of Israeli families—tens of thousands of whom have seen loved ones injured and killed in Palestinian terror attacks—to Brennan’s disappointment in them (though it is hard to imagine printable ones). Even more striking than the barely veiled antisemitism in the ex-CIA chief’s public pronouncements is his unctuous hypocrisy. Tell it to the victims of your drone strikes, John.

Brennan’s comments were ostensibly prompted by a Palestinian short film called “The Present,” which tells the story of a Palestinian man who crosses Israeli checkpoints with his young daughter to buy an anniversary gift for his wife. His frustration and anger grow as he makes his way home until he is on the “verge of violence,” writes Brennan. The movie reminded Brennan of his own experiences traveling to Israel in 1975, when he saw Palestinians at a West Bank checkpoint “subjected to discourtesy and aggressive searches by Israeli soldiers.” He acknowledges that the Israelis had legitimate security concerns and still do—Hamas, as he writes, continues to fire on civilian Israeli homes. He also recognizes that Palestinian leadership is corrupt. But the real problem, he says, is the “diminished interest that the Israeli government has shown in pursuing a two-state solution.”

Tell it to the victims of your drone strikes, John.

Of course, no one is in favor of young soldiers showing discourtesy at checkpoints. But in blaming the Israeli government for its own security concerns and the sorry status of the two-state solution, Brennan failed to mention that Palestinian Authority President Mahmoud Abbas chose to sit out U.S.-sponsored peace talks in 2020, when the Trump administration promised an eventual Palestinian state as well as $50 billion in immediate international investment. The “moderate” Abbas has similarly rejected every offer made by Israel or any third party for the past 15 years. Even more strangely for a former spy chief, Brennan takes it as a good sign that the Biden administration has restarted funding for “development programs” that the Palestinian leadership in fact uses to pay terrorists who kill Israelis, a form of aid the Trump White House had previously cut off.

Since leaving government, Brennan has used cable television and social media as platforms to push the Russiagate conspiracy theory, sending American public discourse into a fetid sewer from which it has yet to emerge. While his overripe fulminations did little to convince anyone that he had a case, Brennan repeatedly broke a longstanding rule against U.S. security chiefs engaging in partisan politics after leaving office—setting a precedent for the acceptable weaponization of intelligence that seems likely to become the new rule.

All this is not to say that Brennan doesn’t have deep experience of the Arab world; he does. His 2013-17 term as CIA director capped off a 30-year career inside the U.S. intelligence community during which he held several senior posts, including station chief in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Brennan speaks Arabic, and even before his career in the spy services he showed interest in the Middle East and Islam. Given the amount of intelligence he has consumed over his career, and the number of meetings he attended with high-level Israeli and Arab officials—from the Gulf Cooperation Council states to U.S. allies like Egypt and Jordan—there is no one better placed to make the U.S. national security case for prioritizing the Palestinian-Israeli peace process.

The fact that Brennan, of all people, doesn’t even try to make that case is revealing. With his emotive (rather than analytical) movie review and tweets, he inadvertently pointed to a key new assessment: There is no genuine U.S. security or intelligence case that supports prioritizing or even pushing Palestinian statehood.

Brennan is right that the daily circumstances of ordinary Palestinians are tragic. Most simply want to lead dignified lives, enriching and enjoying their families and communities. The fact that many can’t, however, is not the fault of Jerusalem or Washington, nor even primarily of the Arab regimes, which for so many years used the Palestinians as pawns to advance their own domestic and international interests. With the Abraham Accords, a coalition of prominent Arab states publicly and unreservedly gave up on the rejectionism that still drives the sclerotic ruling cadre in Ramallah, and embraced Israel’s dynamic economy, society, and military as models and partners. Shimon Peres’ dream of real peace finally started to materialize under Netanyahu and Trump, two men he abhorred. But it came true nonetheless.

For Brennan, the palpable tragedy here is not the fate of ordinary Palestinians, who often get lost in the shuffle, or even the moral well-being of Israelis who insist on protecting themselves against terror attacks. It is the fact that the house of cards he spent 30 years building on the Resolute desk came crashing down.

Now it is clear for all to see that the decades Brennan and his colleagues spent working on the Middle East were wasted on wrongheaded myths and sentiment. They had access to endless acres of the most highly classified intelligence assembled by the most powerful country in the world, but somehow, they misread it. They were wrong about the peace process, wrong about Israel and the Palestinians, wrong about the politics of the Middle East. What they spent their careers passing off to policymakers weren’t precious secrets that explained the laws of political gravity, but poetry in translation.

Lee Smith is the author of The Permanent Coup: How Enemies Foreign and Domestic Targeted the American President (2020).