Late one Saturday last fall, I met Gregg Roman, the director of the community relations council for the Jewish Federation of Pittsburgh, in the lobby lounge of the DoubleTree hotel in midtown Manhattan. Roman, 29, was in town to attend a meeting of the board of directors for the Jewish Council for Public Affairs. He and Sotloff met as students at the IDC, in Herzliya, Israel, while Roman was trying out for the debate society.

“It’s not enough for us to learn about [the Middle East] in class,” Sotloff would say to Roman as they puffed away at Romeo y Julieta cigars and took in the view from his friend’s apartment—Lebanon to the north, Jordan to the east, Egypt and Gaza to the south. “We have to go there to really understand what’s going on.”

On his way toward my table, Roman ran into Ronald Halber, the executive director of the Jewish Community Council of greater Washington, and invited him to sit with us. Halber, I was told, was the main point of contact for all governmental and Jewish media relations for the family of Alan Gross during his imprisonment in Cuba. “That could be your next story,” he said.

For two hours, Halber gulped cocktails while Roman downed double-whiskies, excusing his thick, 6-foot-4-inch frame from time to time to take smoke breaks. “I’m mad,” he said when he returned, referring to Sotloff’s murder. “I want revenge.”

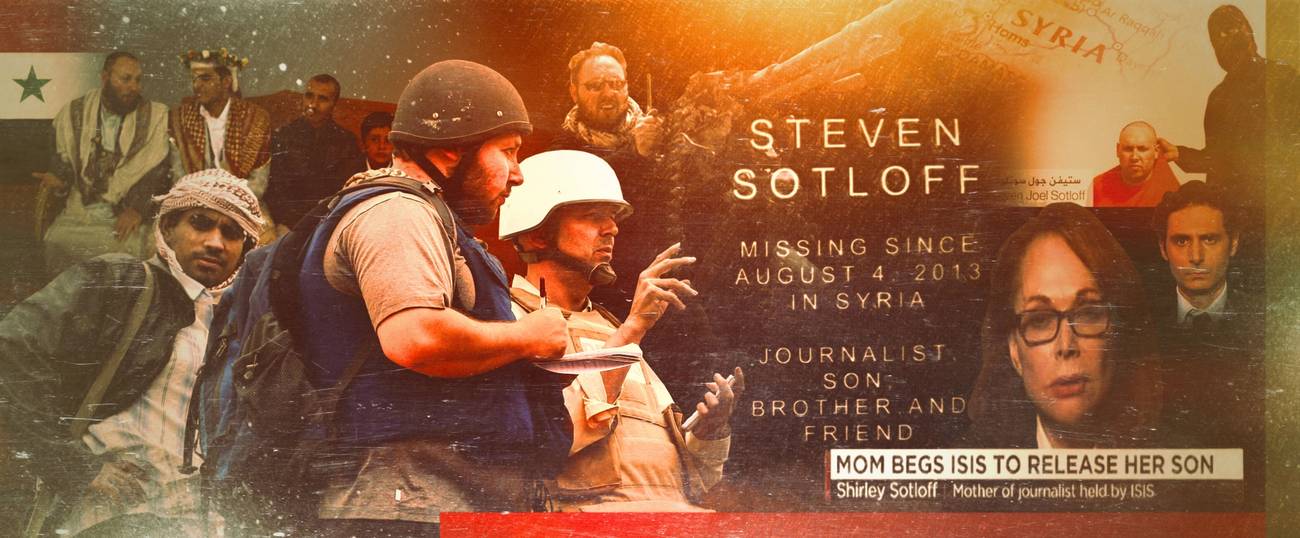

On Aug. 19, 2014, a little over a year after Sotloff’s capture, Mohammed Emwazi, known colloquially as “Jihadi John,” moved behind James Foley. As the camera rolled, Emwazi sliced Foley’s throat and killed him. In the next frame, viewers are introduced to Steven Joel Sotloff, who kneels next to Emwazi just like Foley had. Emwazi wrests the collar of Sotloff’s orange jumpsuit, similar to those worn by “non-compliant” prisoners at Guantanamo Bay. Emwazi speaks: “The life of this American citizen, Obama, depends on your next decision.”

For the Sotloff family—parents Arthur and Shirley, and younger sister Lauren—it was proof of life for their only son and brother.

It was also a game-changer. As a condition of their negotiations with the Islamic State, the Sotloffs were under direct orders not to speak to the press about information regarding their son’s kidnapping. If they did, any chance at negotiating Sotloff’s release would end. Art Sotloff told me that three months after Steven was taken, ISIS sent an email to five addresses stored on his son’s computer, which the jihadists had taken. Two of the addresses were simply inaccurate emails, and one was misspelled. The other two emails were addressed to Barfi and to Art. It’s Barfi who discovered their email, Art told me. In it, ISIS demanded 100M Euros and directed the family to stay silent during negotiations—which they had.

The Sotloffs had held up their end of the bargain, but with the release of the video of James Foley’s murder, which broadcast Sotloff’s identity to the world, ISIS had violated its own rules.

The video also activated the wide group of people whom Sotloff had met and affected throughout his young life.

His old rugby coach recalled watching CNN in his apartment and seeing Sotloff at the end of the Foley video. “I was like, ‘Oh my God, that’s Steve,’ ” McMahon told me. “You make the connection—I haven’t heard from him, he hasn’t surfaced. I thought, ‘How’s he going to get out of this?’ ”

When Roman saw the video of his imperiled friend, he said, “Holy shit.” He immediately looked on the Internet to see what information about Sotloff came up. On Sotloff’s Facebook page Roman came across pictures from his college graduation from the IDC Herzliya. Roman’s own Facebook feed was blowing up with posts from mutual friends from the school. Soon he received a phone call from a journalist who desired information about Sotloff. A bell went off in Roman’s head: If the international press starts reporting about his Israeli identity, they will kill him.

Roman called the FBI special agent in charge of Pittsburgh, who gave Roman’s number to a counter-terrorism agent. Roman said that when they spoke he got no information from the agent but revealed as much as he knew about Sotloff to the FBI.

Next he called Benny Scholder, Sotloff’s best friend and former roommate in Israel. He asked Scholder for a phone number to reach Steven’s parents, but Scholder didn’t have it. So Roman searched the White Pages online for “Arthur Sotloff.” He found a listing, called the number, and it rang until it reached the answering machine.

“Hi, my name is Gregg Roman,” he began. “I work at the Jewish Federation of Pittsburgh. I was a friend of Steven’s at the IDC in 2006 to 2008. We also worked together on Al-Jazeera”—someone on the other end picked up the phone. It was Arthur Sotloff.

“Do whatever you can to help save our son,” he said.

Arthur Sotloff gave Roman the phone number for Barak Barfi. When Roman called Barfi he was in Gaziantep, a large Turkish municipality about 35 miles north of Kilis, a town near the Syrian border where Sotloff spent his final days as a free man.

According to Roman, Barfi had set up an intelligence center in Turkey.

“I don’t work in the intelligence community,” Barfi told the BBC on Feb. 26, the day after “Jihadi John’s” identity was revealed. “I don’t have a view into that.”

Scholder added Roman to a Facebook group called “Bring Him Home,” which was started by Tanya Sklar, Sotloff’s classmate at the IDC. The group would serve as a private forum in which Sotloff’s friends from the IDC—by then located in Israel, the United States, Europe, Canada, and elsewhere around the world—could communicate. The Facebook group, which began as a place to emote, share news about their captive friend, and reconnect, grew into a grassroots media monitoring collective that worked for two weeks to censor, by subtraction, Sotloff’s Jewish and Israeli affiliations from the Internet—an integral part of a wider strategy to save Steven Sotloff.

Tablet has obtained a copy of the Facebook discussions that began on Wednesday, Aug. 20 at 4:29 a.m. EST, and concluded on Sept. 3 at 6:59 a.m. EST. Tablet has also obtained recordings of nine conference calls—beginning Aug. 25, and ending on Sept. 2, the day that Steven Sotloff was killed—that involve members of the media-monitoring group; Barak Barfi; Arthur Sotloff; William Daroff, the vice president for public policy and director at The Jewish Federations of North America (JFNA) in Washington D.C.; Steven Rabinowitz, a former staffer for Bill Clinton; and Moti Kahana, an Israeli-American entrepreneur with ties to Syria. Together, they provide evidence and insight into the Sotloffs’ overall strategy to save their son that involved the advisement and connections of members of the Foundation for the Defense of Democracies in Washington, D.C., as well as an effort to raise funds within the Jewish community at large, with the money going to support the expenses of the Sotloff family and Barak Barfi and to Control Risks, a consulting firm that specializes “in helping organizations manage political, integrity, and security risks in complex and hostile environments.”

While most of America was sleeping, Sotloff’s friend Oliver Charles Kent told the “Bring Him Home” group that the top brass at the IDC, including university president Uriel Reichman, were aware of Sotloff’s affiliation to the school, and that they were “weighing the risks of notifying people not to post on social media versus the danger of alerting more people.” Kent encouraged the group to keep quiet for as long as possible. Stevie Weinberg, the director of operations at the IDC’s Institute for Counterterrorism (ICT), confirmed for the group that Sotloff’s affiliations were being discussed “with various terrorism experts.” Weinberg confirmed that these discussions included Reichman and Boaz Ganor, Weinberg’s boss, who was also Sotloff’s instructor while he was an IDC student. Weinberg wrote that Ganor had said that keeping Sotloff’s Israel/IDC connection hidden could “make a huge difference.” Weinberg added that he had spoken with the former head of negotiation and kidnapping unit of the IDF, who said that “if a google search can link [Steven Sotloff] to Idc we should create fake website in various languages to confuse them if needed.” Later, Weinberg, who would help to monitor the Arabic press, told the group, “There is an online situation room in IDC with hundreds of volunteers that can help scan the Web or boost a fake website.”

Weinberg, who declined to comment for this article, advised the members of the Facebook group against mentioning Sotloff’s connections to Israel or the IDC, or to any information that linked their relationship to Sotloff (as classmates). “The Idc,” he continued, “will not confirm any links to Steven in the meanwhile.”

Members of the Facebook group began to take down their own posts about the situation, or refrained from posting, and encouraged others from their years of attendance at the IDC to do the same. A couple of Steven’s American classmates, for instance, had posted the news beginning with, “My college friend …”

Members of the group began to notice articles about Sotloff on Hebrew-language websites Ynet and Mako. Though they did not link him to Israel, it was being reported that Sotloff wrote for The Media Line. Another group member mentioned that i24, a Tel-Aviv-based news outlet, had posted an article the night before that mentioned Sotloff’s affiliation to the IDC, as well as the fact that he’d written for The Jerusalem Post and The Times of Israel, but that it had been changed by morning. “The Jewish press are already aware of it so it may be a hopeless cause now,” wrote Kent. “But we should try to keep it quiet for as long as possible.”

“Anyway, ISIS already know who is he,” wrote Noam Assouline, an IDC classmate, in the faulty English of Facebook chat. “Let’s all pray for him and try to think of a way so he will remain in our heart and soul no matter what happen.”

“I don’t know if that’s true Noam,” Kent replied. “They would have gloated they have a Jew who studyied in Israel.”

Scholder wrote, “Guys, honest question … do we really believe that [Steven’s] captors, who have had him for A YEAR already, and have been able to do god knows what to him, and who are known as being tech savy, aren’t aware of his Israel/Jewish connection?”

The group worried about Sotloff’s Facebook page, which contained posts from 2010 that were written in Hebrew and mentioned Israel: Sotloff, for example, had “liked” Hadag Nachash, a left-leaning Israeli hip-hop/funk band. Sklar pointed out that in one post, Sotloff had written, “ שנה טובה,” a greeting for Rosh Hashanah, the Jewish New Year.

“Luckily Steven scrubbed a lot of the online connections to Israel a couple years ago,” wrote Loren Baum. “I remember talking to him about this before he started traveling long-term.”

Baum, a New York-based PR professional, mentioned that CNN was looking for someone to speak on the issue and floated the idea that an increase in media attention might put pressure on the Israeli government “like Gilad Shalit,” who was held captive by Hamas for five years before the Israeli government negotiated his release in exchange for 1,027 prisoners. Avi Hyman, a PR professional for the IDF, disagreed, writing that the video the Islamic State released looked like it was pulled from the HBO show, Homeland. ISIS, he wrote, was creating a “theatre of terror.” “This is all part of their plan.”

The group understood that a CNN reporter would more than likely ask how any of them knew Sotloff, and that they’d be forced to divulge their IDC affiliation—which would be counter to their current efforts. Sky News (UK) and Arutz Sheva (Channel 10, Israel) also reached out to individuals in the group, as did New York Post reporter Danika Fears. “Everyone should remain silent and let his family’s rep coordinate,” wrote Roman who was in touch with Sotloff’s father the night before. “Everyone who needs to know, knows.” He told everyone that the family was aware that a group of Sotloff’s friends from the IDC were ready to help.

“I can confirm everything Gregg has said,” wrote Scholder. “I was just wanting for him to say it first.”

With the cat out of the bag, the Sotloffs created a petition on WhiteHouse.gov. It read, “We, the undersigned call upon you, President Obama, to take immediate action to save Steven’s life by any means necessary.”

Lauren Sotloff’s boyfriend posted a link onto his Facebook page accompanied by the following text:

THIS GOES OUT TO ANYONE & EVERYONE THAT HAS A HEART & SOUL….

MY GF Lauren Sotloff’s brother Steven Sotloff was taken hostage by ISIS on August 04 2013 & up to this point it has been all under wraps as due to a media blackout i or anyone else couldnt bring this to light,TIL NOW as it’s gone public that JAmes Foley was beheaded in social media & they claim that if BARAK OBAMA doesn’t stop the bombing ,Steven Sotloff is next. Listen i know im one to publicy things on the internet thru my many social media ,but this is problaly one of the most important post i will ever put up.

People please not only sign the following petition ,but PLEASE SHARE so the more the better. Thank You in advance & pray for his safe return home.

The “Bring Him Home” Facebook group agreed to privately circulate the petition as well, and by Saturday, Aug. 20, 2014, over 3,000 people had given their endorsement. Baum predicted that it would reach 10,000 signatures by the end of the weekend, a good sign if it were to reach the necessary 100,000 within 30 days. (It never did—the petition was made moot as Sotloff was killed less than two weeks later, peaking at just 11,566—and it has since been archived on the White House’s website.)

Around 5:00 p.m. that day in Israel, Channel 10 broadcast news of Sotloff, who was identified as an American journalist, and made no mention of his connections to Israel. CNN, the BBC and The Telegraph, too, reinforced that identity. It seemed, for now, that the information—a secret, so to speak—was safe.

When newcomers were added to the Facebook group they’d be updated as to the rules of privacy they were operating under—that they should not publicly link themselves to Sotloff, or link him to the IDC or Israel. “Or his being Jewish,” added Scholder. “We don’t want this going ‘Daniel Pearl.’ ”

Sotloff’s friend Nate Perski told the Facebook group that the cousin of Ronit Epstein, a “Bring Him Home” member, had received a message from Sotloff’s account on Aug. 20 at 4:24 p.m. Israeli time, a few minutes before Obama’s speech.

“I have been kidnapped by ISIS,” the message read, and included a link to an article on the New York Daily News website.

“This is insane,” wrote Assouline.

“I don’t understand,” replied Baum. “From Steve’s Facebook account?”

Sotloff hadn’t updated his Facebook page since August 2013, but his friends had noticed that Sotloff’s profile now showed his real name rather than “Stove Sotty,” a nickname he’d previously had listed. The group had deduced that ISIS was possibly behind it due to the fact that Sotloff’s full name, Steven Joel Sotloff, was posted in a graphic in the Foley video, which ISIS had gotten from Sotloff’s passport. They wondered if ISIS had gained access to Sotloff’s Facebook account password; IDC classmate Jonathan Jawitz had seen that Sotloff had rejoined on Aug. 20, 2014, and wondered if his account had been deactivated and reactivated again.

Larroche sent a private message to Lauren Sotloff to find out who had sent the message. She believed that the family was logged in to his account.

“I got a message from steve (sic) too,” wrote Nicole Jarmusz. She had read the message at 6 a.m. Israeli time, and, suspecting that ISIS had taken control of his account, unfriended Sotloff.

Another member of the group noticed that Sotloff’s Microsoft messenger was online, signed in through his Hotmail email address. Like Larroche, Roman suspected that the family was logged in. Still, they weren’t sure.

Roman suggested taking screenshots. “We would have sent them a message with a link to a website that I could record the IP address were they to click on that link,” said Roman. From the IP address, Roman believed that he could work to geolocate the user who had access to Sotloff’s account, then give that information to the FBI representatives who were working with the Sotloffs.

Roman said that he was never able to figure out who was sending messages from Sotloff’s Facebook account.

Sotloff’s Facebook account, which has been excised of sensitive posts, and even deactivated for a stretch, currently shows just one post, made on July 23, 2013, about a week before he was kidnapped.

Around 2 p.m., Roman had a conversation with the Sotloffs and reported the family’s message back to the group:

[We] ask that you pray for Steven. [We] appreciate all the warm thoughts on this conversation and thank you for your support. Please DO NOT speak to anyone about his connection to IDC or any ancillary body. This is being dealt with at the highest levels of government. DO NOT share this information with anyone. Please also do not contact press or private organizations and make note of his connection to how we all knew him. Do not speak to the press. If a member of the press approaches you, make sure we know about it so we can minimize exposure. Thank you for everything you are doing and continue to pray for Steven.

“That’s it,” Roman wrote.

“Any news about his situation?” asked one member of the group.

“Nothing,” Roman replied. He suggested that sharing pictures in which Sotloff could be seen with Israelis, or ones that included the word “Hebrew” in it, was not a good idea. “I’m sorry to be the downer,” he wrote.

“You can have his slate cleaned from google and erase any traces he may have left regarding his connection to Israel,” wrote Uri Goldflam, the former director of the Raphael Recananti International School at the IDC Herzliya. “Have them call Meir Brand, CEO of Google Israel (and other countries).” He provided Brand’s phone and email.

With the permission of the Sotloff family, Roman contacted Google Israel and asked that it remove the cache of anything referencing Sotloff’s Jewish history—“if there’s danger to life,” said Roman, recalling the “right to be forgotten” privacy ruling in Europe. “I don’t know if they did that though because I never got a response,” Roman later told me. “But whatever they did or didn’t do, it worked.”

Roman was also in contact with the office of the Israeli Military Censor, which issued a blackout order to the Israeli press barring them from publishing information that connected Sotloff to Israel or to the IDC.

“This is now an ISIS-AMERICAN narrative,” Roman wrote to the group. “To introduce Israel is NOT in steven’s interest.”

Around 1 p.m. on Aug. 21, Roman reported to the group that he had spoken with the family, who had confirmed that Steven was alive. “They’re not speaking with the media,” he wrote.

Many members of the Facebook group were monitoring the discussion round-the-clock, often from work or during mundane day-to-day tasks like shopping at Ikea, or when family was in town visiting. And as time went on, the emotional toll became worse. For instance, Sklar had to step away to take a walk on the beach to clear her head. “I’m just so upset about this,” she wrote when she came back. “Steven can’t go for a walk to breathe.” In time, members of the “Bring Him Home” group gathered in a separate forum dedicated to supporting each other emotionally. And a few days later they gathered in person in Petah Tikvah, a city just east of Tel Aviv, to “restore some balance.” At one point, one member of the group checked in from a delivery room in Jerusalem, where his wife was giving birth. “My thoughts have been dark of late bringing a new baby into this reality,” he wrote. “But the performance of this generation is giving me hope.”

Sotloff’s IDC friends received some insight when The Daily Beast published an article by Ben Taub, the photojournalist and writer who had had beers with their friend in Kilis on Aug. 1, three days before Sotloff was kidnapped. Taub’s account, which centered around Sotloff’s fixer, also relayed familiar and regrettable information to Sotloff’s friends—that Sotloff had told him “he had had enough. … But first he wanted one last Syria run. He said he was chasing a good story, but kept the specifics close to his chest.”

On the morning of Aug. 22, Roman communicated with the group the advice he had received from a kidnapping and ransom adviser as to the purpose of the “Bring Him Home” collective. Roman told the group that someone would soon be taking his place as the main point of contact between the media monitoring group and the family. It never happened.

Articles about Sotloff were being published at a rapid rate, and members of the “Bring Him Home” raced to keep up. At first, the operation was roughshod, even confused, and occurred on a case-by-case basis. But over the next few days, a system began to take shape. Roman communicated with the group its purpose, on the advice of experts with whom the family had agreed: “To reduce exposure in the public domain of the kidnap event circulated by individuals, media and other third parties. The working assumption should be that all the information is known to the kidnappers. This is the most likely scenario. However, it is important to reduce media coverage or details which will be then manipulated by the kidnappers. All activities should be set towards the defined objective.”

Red flags were raised early and often. For example, Emerson Lotzia, Sotloff’s roommate at the University of Central Florida, who now works for an ESPN affiliate in Florida, gave an on-camera interview with Fox 35 in Orlando. “He always talked about wanting to kind of retrace his Jewish roots,” he told the station. Lotzia also told the Miami Herald that he had spoken with Arthur Sotloff the day that the video was released. “He was in the best of spirits, then he was in the worst of spirits,” Lotzia told the reporter. “ ‘At last I know my son is alive,’ Arthur Sotloff had told Lotzia, “but look at the situation.” Roman contacted Lotzia, who agreed not to speak to the press any longer.

But the media kept digging. The Daily Mail (UK) reported that Sotloff’s grandparents were Holocaust survivors, citing Shirley Sotloff’s biography from the website of her employer, the preschool at Temple Beth Am in Pinecrest, Florida. A member of the group reached out to the newspaper and the information was removed from the article. Her bio was taken down from the temple’s website, and Roman worked to get the index deleted. (Shirley Sotloff’s biography, which mentioned that she is “passionate about preserving the memory of The Holocaust, as both her parents were survivors,” is now back on the synagogue’s website.)

On Aug. 21, just before 2 a.m. EST, Sklar asked Roman: “Shall we read all online papers around the world looking for any mention and let u know if there is? Would that help?”

He suggested beginning with a Google search for “Steven Sotloff” + “Jew” or “Israel”.

“يهاد is Jew, سثبي is Steven and سايلق is Sotloff,” Roman wrote.

Eventually, the group turned to DuckDuckGo, a search engine that does not track users. Sotloff’s friends network searched the media in various geographical markets—U.S., U.K., Australia, etc.—and languages, including Arabic, numerous Balkan and Slavic languages, French, Serbian, English, Bosnian, Croatian, Balkan, Italian, Swedish, Spanish, Portuguese, German, Russian, Polish, and Spanish. They also began to monitor social media, including Twitter and Facebook, for three pieces of sensitive information about Sotloff that was deemed to be potentially endangering: his Jewish roots; his life in Israel, including the fact that he had Israeli citizenship, and had attended and graduated from an Israel-based university (IDC); and finally, any insights into the negotiations the Sotloff family were engaging in.

Sotloff held numerous social media accounts, including Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and LinkedIn. At the time, Sotloff had just six connections on LinkedIn—his friend Nate Perski estimated that four of them had relations to Israel—and was following University of Central Florida, where he attended college for two years. Sotloff described himself as a “traveling man.” Roman recommended to those who were linked to Sotloff on LinkedIn that they should break the connection and reach out discreetly to others to do the same.

When a piece of sensitive information was found, the group would assess its risk and work to get it eradicated. At first, when a member of the group would find an article with sensitive information, they’d post it to the forum and it would typically be Roman who would get in touch with the author, or publication. He’d explain the situation and ask that the sensitive details be taken down. Soon, Baum created various ways to streamline the tracking processes. For example, when information written in an article about Sotloff caused an alert, a group member could submit a link, which would be centralized in a Google doc, along with the contact information for the author, which would be obtained either through Cision, a media contacts database, or likelier, via a simple Google search.

Sometimes, details of an article would be taken down on websites, but they would remain on Facebook. In this case, members of the media monitoring team were instructed to reach out to the publications with the following script: “I was asked to forward this by the Sotloff family (Arthur and Shirley) representative, Gregg Roman. He can be reached at XXX-XXX-XXXX. Your article removed all references to his being Jewish yet this summary still has it. We were in touch with the editorial staff this morning. Please take down this post and remove any reference to his being Jewish. This could jeopardize Steven’s life! Thank you for responding to this swiftly.”

Others publications, such as South Florida’s Sun Sentinel, did not immediately respond, as the New York Times did to one such request, but did eventually take down reference to the sensitive information. It was even covered by a blogger, Debbie Schlussel, whom the group called the “Jewish Ann Coulter.” She wrote: “Then there is Sotloff. He’s a Jew who was based in Yemen. Moron, or I guess, in his case, Moronowitz. What kind of Jew hangs out in Yemen and Syria? A dumbass and an apologist. And, most likely, a selfhater. Incredibly, this Sotloff dummy—who will be next to the slaughter (N O W A Y they will spare a Jew, no way—Daniel Pearl’s silly insistence that he was a Buddhist, or whatever, didn’t matter) wrote an article in 2010 warning that the Muslim Brotherhood was evil. Um, well, who did he think comprised the ISIS gang in Syria? The North Dakota Society of Wiccans?” Roman contacted Schlussel, who agreed to take the information down.

The list grew and grew and perhaps most of all on Twitter, where a group began to track two hashtags as: #StevensHeadinObamasHands, and #AmessagefromISIStoUS. Baum automated a number of these searches. Sometimes a Tweet might spark an alert but would soon be deemed benign. Such was the case with a random Tweet that read, “Beheading Steven Sotloff IDC IDC IDC.” The “IDC, it was determined, stood for “I Don’t Care” rather than the Inter-Disciplinary Center of Herzliya, hence connecting Sotloff to Israel.

Later Roman suggested that they monitor the hashtags: #Jew #Zionist #Israel and #Yehud. A problematic picture of Sotloff was also circulating on Twitter that the group deemed to be endangering. In it, Sotloff mans a machine gun—identical to the picture he submitted to his high school’s magazine update—cropped next to a picture of Sotloff in his orange prisoner garb, with Emwazi’s hand wresting his collar. A version of that picture still exists online that reads: “Beheaded Journalist Steven Sotloff Israeli Spy? Zionist Mole?”

With the amount of information swelling, and the stakes seemingly rising, Roman knew that the effort had to become professionalized. He brought on Brett Goldman, a political, business, and communications consultant based in Washington, D.C. He and Roman were classmates at the IDC (Goldman never met Sotloff), and he is currently a consultant at the Jewish Federation of Pittsburgh, Roman’s employer.

“What we were doing was monitoring the hashtags, and as things came up and as we found them, we passed them on to the security team on Twitter,” said Goldman.

On Aug. 24, he said, he was walking on the beach with his father when he received a call from Roman. The friends had been speaking since Sotloff appeared at the end of the Foley video and Roman asked Goldman for help. Goldman said, “As soon as Gregg said, ‘IDC grad, captured by ISIS, need your help,’ what am I going to say—No? Of course I’m in.” Roman also brought on Goldman’s friend Jarad Geldner, a registered lobbyist and PR specialist who cut his teeth during Toyota’s 2010 recalls and now runs the D.C. office of Red Banyan Group, a PR firm based in Florida. Both Geldner and Goldman, as with everybody else, helped out on a pro-bono basis, sometimes putting in 22- to 23-hour days. “My grandparents were Holocaust survivors,” said Geldner. “I don’t fancy myself any kind of superhero, but when you have the chance to work toward saving someone’s life. For me that was the motivation.”

Around this time, Peter Theo Curtis, an American journalist who had been held by Islamists for two years, was released and handed over to U.N. officials in the Golan Heights. On the morning of Aug. 25, the media monitoring group, including Roman and Goldman, held a conference call along with four of Sotloff’s close friends from the IDC Herzliya.

“Is it me or is this whole thing affecting anybody else’s sleep?” Roman asked the group. “You feel like you have to check your email for a Google alert or tweet every two minutes. If this thing goes on for a while it’s important to set shifts so we’re not going crazy. If our friends in Israel can put up with rocket attacks for 50 days, we can put up with interruptions in our sleep patterns.”

Around 8:40 a.m., Roman told the group that he had spoken with the family the previous day and that there were more people involved than he had previously been aware of. “We are one team among 10 different teams working on this,” Roman estimated. He informed the group of a political group operating in Washington, D.C.; the Jewish community in Florida that was involved in fundraising; a media team in Florida; the Sotloff family as a unit; and a psycho-social support team that was helping the Sotloffs with pastoral care. Roman’s wife was now six days overdue to give birth, and his older daughter could be heard crying in the background. He told the group that it might make sense for the media monitoring group to engage with a psychologist.

That same day at the Atlantic Media Group’s offices in Washington, D.C., Shirley Sotloff recorded a video in which she pleads for the life of her son to Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, ISIS’ leader, whom she refers to “the caliph of the Islamic State.” With the Sotloffs under orders from ISIS not to speak with the press, the Atlantic Media Group had been aiding in the effort to keep the news of Steven Sotloff’s kidnapping under wraps. But with their son symbolically inches—and for all they knew literally hours—from death, the Sotloffs planned to release Shirley Sotloff’s plea video onto major jihadi forums frequented by members of ISIS. It would then be published on the New York Times and to either al-Arabiya or Al Jazeera.

On Aug. 26, members of the media monitoring group held a conference call. On the call was Roman; Jarad Geldner, who was introduced as the day-to-day PR contact with the Sotloff family and who was handling the local Florida media; Brett Goldman, who monitored Twitter and the social media space at large; Michael Bassin, a former Arabic translator for a combat unit in the IDF, who had done “extensive security work;” Loren Baum, who was taking care of the technical aspects of the project; William Daroff, the senior VP for public policy and head of the Washington actions office of the North American Jewish Federations, who was also reaching out to Steven Rabinowitz; and Moti Kahana, the Israeli-American businessman who was raising money to provide aid to Syrian refugees in Northern Golan who had, he said, “people in the region involved in the opposition.”

Roman introduced each person and told the group that the video’s release had been delayed. He told them that the family was in Washington, D.C., working principally with Toby Dershowitz, Jonathan Schanzer, and Boris Zilberman of Foundation for Defense of Democracies, who had been providing the family with advice and assisting with liaising with the Florida Congressional delegation to the White House. Dershowitz was unable to join the call.

Baum updated the group, letting them know that all Facebook records connecting Sotloff to the IDC had been systematically erased, and that the forum had moved off of Facebook to ensure more security. Roman said that he had brought on Goldman and Geldner because they did not have a direct emotional connection to Sotloff. Soon a man named Gilad Wax, a kidnapping and ransom consultant with Control Risks, joined the call, followed by Barfi. Roman introduced Barfi as having been on the ground on the Turkish border for the last year. Barfi thanked everybody and said that the Sotloffs appreciated the group’s efforts.

“We changed the whole strategy,” said Barfi on the call. “Moving forward what we’re looking at is a video of an appeal from Steve’s mom to Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi addressing him as the caliph … and asking him to release Steve because as an act of mercy cause he has the ability to do so.”

After Roman told Barfi that they were monitoring both the English and the Arabic languages on Twitter, Barfi asked that someone get in touch with Aaron Zelin, a fellow at the Washington Institute, “the jihadist guy there … all he does is sit on social media and the forums.”

Barfi asked for more opinions.

Kahana chimed in. “It came to my attention yesterday that the wife and the son of the ISIS leader in Aleppo—my guys actually have them under our custody.”

“The head of ISIS in Aleppo?” Barfi asked.

“I don’t want to guess. I want to give you the exact name, copy the passport of his wife and his son. My guys have them under our control. Something to think about.”

Daroff, who had put Roman in contact with the Facebook security department, chimed in. He said that the family should do what they want, as it’s their right, then asked: “But why do we think that ISIS will act differently after seeing the mom in the video? Is there some inside scoop or intel that we have that makes us think this would be effective?”

“Basically we don’t have any options left,” said Barfi. “This is one of the few things that we have. They’re not reaching out to us anymore. We fear the worst and we’ve got to do something proactive. And we do not want to go public to the media, what-not, start giving interviews. They told all of us, ‘no media.’ They violated that when they put Steve on and they’ve been silent since then. We’re working with The Atlantic on this. Some of you read the Washington Post story, how Peter Theo Curtis was released—it was through The Atlantic. So we think this could be our best option at this point and time.”

“OK, basically there’s not much else to do so this is one option that tries to move the ball forward,” said Daroff. “That works for me—I guess. The idea is still to try to make that video viral so that the right people in ISIS see it, or for a greater plan than that—for publicity, for people to be engaged? Or basically there is an audience of one and this is a way to get to him.”

Barfi outlined three target audiences. “Your core audience is ISIS and the caliph. Secondary audience is the Arab world. And your third is American public opinion to move the administration to do something.”

Roman led the discussion to the strategy surrounding the video’s release. “I talked to Toby [Dershowitz] about this. They’re planning on putting it first on jihadi forums and then it’ll get picked up by the New York Times and Al Jazeera.”

Barfi chimed in. “It’s going to be released on the New York Times website, and on either Al Jazeera or al-Aribiya at the same time. And then it’ll go viral from there.”

“Do you have the expected release time yet?” asked Roman.

“No, we don’t,” replied Barfi.

“What we do have is a little bit of time to protect the infrastructure to protect the three things we’ve determined need to remain private: First, Jewish identity, second, the Israeli connection and third any detail or any behind the scenes activities, like ours, or other things that Moti [Kahana] may have brought up, or other things that need to be kept under the lid.”

Roman went over the processes that were already in place including the fact that they were monitoring news stories in 16 languages in Europe, not to mention the North American press.

The topic of discussion shifted to money. The group’s goal was to raise money for a three-month term for the Sotloff’s expenses, including Barfi’s, who was working to secure Steven Sotloff’s release.

“The target amount for the Federation that they were given was $15,000,” said Roman. An account was set up at the Miami Jewish Federation; the organization was acting as the fiduciary agent.

“That’s not going to cover three months, or six months even,” replied Kahana. “Not even close to three months.”

“That was just a short-term infusion,” said Barfi. “We’re spending like $1,000 a day.”

“Then you think $100,000 should be the number for the next 90 days?” asked Kahana.

“Yeah, that’s a reasonable number,” said Barfi.

“Very quick question, to you Barak,” said Kahana. “If I will get you the name of the wife and the kids, outside of putting a movie out there, something to ISIS, if I ask to go and open a channel—direct channel with ISIS—”

“Is it just the wife and kid or is it the Emir as well?” asked Barfi.

“The wife and the kids—one killed himself, the other kid is still alive,” said Kahana.

“He’s not gonna care about wife and kids. They’re not gonna care about wife and kids. If it was the Emir, that’s something else,” said Barfi. “They won’t negotiate for that. But what you could say is, ‘If you kill [Steve], we’ll kill them. That’s all we can use.”

“Is there any sense in trying to set up an alternative channel to Moti’s contacts to ISIS?”

“We have ways [of getting in contact with ISIS],” said Barfi. “We know who’s running the show there in the prison.”

“Then I will get you the name of the wife and the kids just for you to know it’s available,” said Kahana.

Before they hung up, Daroff added that a man named Jacob from the Miami Federation was going to call Ami Eden, the publisher of the JTA, to have a conversation with him about keeping the sensitive information under wraps.

“Are the political connections still being run by Toby?” Roman asked Barfi.

“Yes, Toby is looped in on all that stuff.”

Roman ended by saying that the group should begin to draft statements regarding all possible scenarios once the video dropped.

“I appreciate you carrying the banner, quietly,” Daroff told Barfi.

“No, it’s you guys that are amazing, coming together this quick,” Barfi said. “Art Sotloff is here, he’s sitting on the phone and we’re just looking at each other and saying, ‘Thank god we have you.’ ”

In a subsequent conference call, Rabinowitz shared with Daroff a dream he had the night before.

“You and I were at lunch and we were joined by a just-off-the-plane, unshaven, overweight Bibi Netanyahu. He was very heimishe … and not looking so great, and it was just weird.”

Roman said that Kahana was on vacation with his family and therefore wouldn’t be joining in on the call. In fact, the impending Labor Day weekend was beginning to rear its head as communications and the holiday weekend came at odds.

“We need a White House meeting,” Barfi told Geldner, “with [Homeland Security Adviser] Lisa Monaco where she can actually talk to me frankly to tell me the options we have, the government has, the intelligence they have, whether they’ve been split up, and whether Steve’s even alive—and will they negotiate, are they willing to talk?”

Barfi shared with the group that he was going to be traveling to Egypt in the next couple of days. “I need to travel, so I need some money,” said Barfi. “I need some money to move around myself. I’ve got my own expenses when I go to the region.” During the time of the call he said he was waiting to meet with Jonathan Schanzer at the office of the Foundation for Defense of Democracies.

“I’ll tell you what we need fund-wise,” said Barfi. “We need several funds. We’ve expensed about 15 grand so far in our effort—minimal expenses, taking buses and the cheapest flights and stuff. So, we need to cover that. Secondly I need to secure the guy working for me, I need to give the guy some money. Thirdly, we have been in touch in formal context with a K&R [kidnapping and ransom] firm, informally advised us. We probably need to bring them on professionally. I have to talk to them about what that would cost.”

Barfi would later mention that his “K&R” contact was Matt Boynton, a former CIA case officer who is the director of response at Control Risks. Roman estimated that hiring Control Risks would cost about $2,500 a day. Gilad Wax pointed out that it would likely be even more than that, and Barfi replied that he could negotiate the rate. In a subsequent conference call, Barfi outlined the costs he’d been provided with, mentioning that his contact was Boynton. “They charge a lot of money but if they get in on this case it’s probably the biggest K&R case ever,” said Barfi. “They’d get a lot of prestige with that, to say that, ‘We were involved in the ISIS case with the Americans.’”

“I’ve spoken with Boynton. This is what he told me a long time ago. They want, up-front escrow 50,000 Pounds; consultant rate 2,440 Pounds a day; research at 230 Pounds an hour; management 300 Pounds an hour—whatever. We’re not gonna give him $4,000 a day for a month, that’s insane. We’ll negotiate.”

With Barfi’s travel expenses, the Sotloffs’ expenses, and the K&R firm, Barfi and Roman estimated that costs would top US$100,000.

Roman and Daroff began to brainstorm potential donors to the cause, as the Miami Jewish Federation was looking to raise $15,000, a far cry from the $100,000 they had just outlined that they needed.

“Is this something that Jerry Silverman would take interest in?” asked Roman, referring to the group’s fundraising mission and Jewish Federations of North America head Jerry Silverman.

“I briefed him,” said Daroff. “It’s sort of a problem throwing not-for-profit dollars because we’re very transparent—”

“Let me rephrase the question,” said Roman. “If there would be people that Jerry, like, names, that he might be willing to give over that Barak or Jarad might be able to call.”

“Yeah, I can definitely have that conversation with him.”

“You guys know Sheldon Adelson, right?” asked Barfi. “His wife is an old friend of my parents, her ex-husband delivered me. We have not been able to get ahold of her because we’re blocked by her people in her office—we called her medical office. If anyone can get to her I can put my parents on the phone with her.”

“What about Matt Brooks, William?” asked Roman, referring to the director of the Republican Jewish Coalition.

“Who’s the president of the [Adelson] Family Foundation?” asked Roman.

“Michael Bohnen,” said a member of the call whose voice was undecipherable.

Conversation then shifted to media.

“The Atlantic has taken over the media, so all the media interfaces with them,” said Barfi. “Right now it looks like they’re working with the [New York] Times and the [Washington] Post on all kinds of stories. I’m sure the [Wall Street] Journal will get involved as well because I have a contact there and—this doesn’t leave this conversation—but Steve wrote us a letter—I don’t know if he smuggled the letter out or asked to write the letter—but he specifically asked for one correspondent from the Journal, so we’re going to work with her also.”

Roman asked, “Is there anything in Egypt or in Jordan or in Turkey that we can help you with?”

“In Jordan, we need to get to the Salafis. If we can get someone in the intelligence agencies that could help us map that out and who maybe the government can lean on to help. I don’t need anything in Egypt.”

Barfi said that he was planning to talk to Schanzer about it but wasn’t sure as to the contacts that he had. Roman said that he felt it was important for Barfi to stop in Jerusalem, to brief parties involved in tamping the Israeli press. “I can’t get in without … you know, the way you have to get in,” said Barfi.

“Do you have an Israeli passport?” asked Roman.

“I can’t get in, let’s put it that way,” said Barfi. “Bypass all that shit. I’ll come if they can bypass all that.”

“What if you were to go to the embassy in Amman?” asked Roman.

“Might not be a good idea at the embassy in Amman,” said Barfi. “I could go to Europe.” Roman suggested that he could talk to Daniel Taub, Israel’s ambassador to the U.K., or with Gideon Meir, the former deputy-director general for media and public affairs in the Israel Foreign Ministry.

Barfi said that that might work, considering that he might be going to London “if the Control Risks thing goes through … but I’m certainly going through Germany. If you have those contacts, they can move me in and out (of Israel) without a problem.”

“Gregg [Roman], you’re running the show, so whatever you think is best you do. I trust you and your team that you put together. Thank you guys so much. You save me a lot of hours of sleep so I can be more focused.”

On the morning of Aug. 27, a Wednesday, Shirley and Art Sotloff were waiting in the atrium of the Fairmont Hotel in Washington, D.C., where they’d been for most of the week. They had been meeting frequently with David Bradley, the owner of The Atlantic, who was trying to help save their son. In fact, Bradley has helped many of the families, including that of Peter Theo Curtis, whose release he brokered via Qatar. Art Sotloff said that when he met with Bradley at his offices, Bradley put a number of his employees on the case.

Two weeks earlier, the Washington Post reported that the release of Peter Theo Curtis had indeed come, at least in part, after an appeal made by Bradley, though the piece did not make clear how Bradley came to be involved in cases other than Curtis’. Before publication, I called Bradley’s office and asked to speak with him about his role in negotiating for Sotloff’s release.

A woman named Emily from The Atlantic Media Group called back and explained that she had worked closely with the Sotloff family.

“I assume you’ve spoken to Barak Barfi,” she asked me. I explained that I had. “And I assume he’s probably one of the people who told you of David’s involvement.” I told her I wasn’t at liberty to say who told me specifically. “Well, we worked very closely with Barak throughout the whole process,” Emily explained. “I’ve been working with David—I represent David and the company—I work also, I’ve been involved with these other efforts. I’ve worked very closely with Barak. I need to know your other questions or I’m not going to confirm anything on the record for you.”

I then read to her over the phone my four questions for Bradley:

1. The Sotloffs tell me you spearheaded parts of the effort to save their son. Is that true? What parts? How did they know to come to you? And most importantly: why?

2. Did you commission and pay for Shirley Sotloff’s video?

3. Arthur Sotloff says you enlisted the help of employees. Is this right? Can you tell me who they were please?

4. Someone told me the Atlantic was in charge of informing other media outlets about what they could and couldn’t say about [Sotloff]. Is this correct? Who was in charge of deciding and running this operation?

Emily never replied. Later that day, I heard through the Sotloffs that I wouldn’t be receiving comment from Bradley or The Atlantic.

Bradley is on the board of the New America Foundation, where Barfi is a fellow. Sotloff never worked for either The Atlantic or the New America Foundation, as far as my reporting had shown. In any case, what’s clear is that representatives of the Atlantic were involved with shepherding the Sotloffs through this time. They were also assisted by Toby Dershowitz, who shuttled them around, including attempting to get them a meeting at the White House, which didn’t transpire at the time.

It was just hours from the release of Mrs. Sotloff’s plea video to Abu Bakr Al-Baghdadi, in which she asked him to spare her son’s life.

“I was amazed at how composed they were,” said Geldner.

“I have an image in my head of Steven’s father kind of waiting for us in this hotel, kind of sitting there, and he was calm and [Shirley Sotloff] was very composed,” said Goldman. “This was new to the rest of the world at that point,” said Geldner, “but it was over a year old to them.”

Geldner and Goldman met them for breakfast; Lauren Sotloff was not there, and Barfi was. No government officials were there. Geldner said that he had some low-level discussions to set up a meeting with high-ranking officials in the White House but said that nothing ultimately came of his effort. “Steven’s family wanted a meeting at a very high level in the administration and I think that meeting would have put the White House in a very awkward position,” he said. “My contacts—ultimately nothing came of it.”

This statement is in line with those made by Barfi, who made of number of TV appearances after Sotloff was killed. “We never really believed that the administration was doing anything to help us,” Barfi said on CBS This Morning. “We had very, very limited contact with senior officials. It was basically limited to two FBI agents, and when I tried to ask for a senior point of contact, all the administration said is, ‘You can speak with to the consulate of bureau affairs at the State Department.’ ”

After breakfast, a conference call took place with friends from the Facebook group, and Geldner and Goldman, to give a pep talk and to make sure that everybody was on the same page and ready to take on their roles when the plea video would drop at 11 a.m., about 15 minutes from when the call started. Geldner told the group that he was particularly concerned with the Florida media markets of Miami, Ft. Lauderdale, West Palm, and Orlando. “We have reason to believe they are hot on the trail of this info, and reason to believe that lots of Steve’s captors, being British, look to those sources for information.”

“Brett and I just left breakfast with Steve’s parents,” said Geldner. “The video … will be dropped through the New York Times and through al-Aribiya. We expect that the Atlantic, the magazine, will pick it up very quickly—they’ve been instrumental in laying out the strategy and shaping it moving forward given their outsized role in their releases of captive journalists.”

“It’s on Twitter right now!” said Roman. “It’s live, let’s go, guys.”

“We’ve not seen Steven for over a year,” Mrs. Sotloff says in the video, in which she speaks carefully and blinks slowly. “And we miss him very much. We want to see him home safe and sound and to hug him. As a mother I ask your justice to be merciful and to not punish my son for matters he has no control over.”

Before she shot the video, Shirley Sotloff had her hair done at a Miami salon, which I visited. I saw her longtime hairdresser, a woman who asked not to be named. She told me that she had cut Steven’s hair since he was 12 years old, and that his mother had confided in her about her his captivity. They had cried together, and she welled up when talking to me.

On Sept. 2, 2014, the Islamic State released “A Second Message to America,” an execution video that again featured Emwazi but this time with Sotloff as his primary victim. The video begins like Foley’s had, with a stylized and edited speech from President Barack Obama. “When people harm Americans anywhere,” he said, “we do what’s necessary to see that justice …” Obama’s words now feel ironic, even hollow and untrue, as both Sotloff and Foley, along with Peter Kassig and Kayla Meuller—all Americans—are now dead, despite one failed (and apparently too-late) rescue attempt.

Under coercion, Sotloff speaks as a mouthpiece for his captors. He looks thinner than any picture I’ve seen of him as an adult, a byproduct of his more than year-long captivity during which he was sometimes given just a cup of tea a day.

Larroche also watched the video. “It was Steve, you know?” she told me over the phone. “He looked good. He looked strong. He had that way he talks with his lips—when he talks it goes to the side. That was the way he talks. His voice. He doesn’t have too many facial expressions. He didn’t break or anything like that. It was really weird to see him like that. That was really Steve. It’s heartbreaking.”

He begins, “I am Steven Joel Sotloff. I’m sure you know exactly who I am by now and why I am appearing before you. And now, it is time for my message: Obama … Why is it that I’m having to pay the price of your interference with my life?”

“I’m back, Obama,” says Emwazi. “So just as your missiles continues to strike our people, our knife will continue to strike the necks—”

Sotloff’s eyes close softly, as if to block out the sun.

Emwazi steps behind Sotloff, pivoting his right foot into the desert as his right hand grabs Sotloff’s jaw. He slices at Sotloff’s throat. Sotloff slides his left leg up from a knee as if to attempt to stand, but then falls onto his bottom as the wind continues to blow. In the next scene, the camera pans from left to right over Sotloff’s body.

At 4:30 p.m. U.S. time, 10:30 p.m. Israel time, Roman, Goldman, Daroff, Rabinowitz, Barfi, Steven Weinberg, the director of operations for counterterrorism for the IDC and liaison to Uriel Reichman, the president of the IDC, and Inbal Chen, introduced as the spokesperson for the IDC, joined a conference call.

Though it was late in Israel, Inbal told the group that a number of Israeli media had already begun to reach out to her and Weinberg to confirm whether or not Sotloff had been a student there. They expected the information to be published by the morning, even if the IDC did not confirm it. Roman told the group that Twitter was blowing up with information that Sotloff was Jewish, that he had lived in Israel and studied at the IDC, and that he had written for The Jerusalem Report. By morning, their efforts to quell the press would have imploded.

Roman said that he had tried to get the Israeli Military Censor to intervene, but they were uncooperative. “The amount of information in the foreign press right now prohibits them from issuing the censure order,” said Roman. “I tried up all the way to the prime minister’s office.”

Barfi, sounding exasperated and a bit tired, asked, “So, you’re telling me that there’s nothing we can do?”

“William, is there any way you can call Ron Dermer”—the Israeli Ambassador to the U.S.—“directly and get a bead on Bibi? Is there any way to do that?”

“Sure,” said Daroff. “But tell me why at this point we don’t want it out there that he was an Israeli?”

“Because first of all they will then suspect everyone they have [in ISIS captivity] of having some type of Jewish-Israeli link and they will start torturing those people again,” said Barfi. “And they will risk their lives now. We gotta—this isn’t a Daniel Pearl thing. When Daniel Pearl was executed everybody waited because he was being held alone. Steve is not being held—we do not believe that they even know he was Jewish. Steven was not tortured as badly as the other American and another Brit. They will start suspecting them of all kinds of plots and this is not what we need for the rest of the people in there. You need to think about—look. I want to go on TV and say my peace about what I know, but I can’t right now because there’s other Americans in there.”

Chen suggested that if they were going to get in touch with Netanyahu’s people, that they make a decision as soon as possible, as it was edging into the long nighttime in Israel.

Barfi guessed that Bibi was probably sleeping.

“No, I think he has a video conference with [John] Kerry that’s starting any minute now, so he’s awake, unless it just ended. So I can get to Dermer, but I need to convince him that a military censor needs to stop any information about Sotloff having been in Israel or being an Israeli because our CT experts believe that it’ll put everybody else in danger because they’ll think that they all might be Mossad agents.”

“Exactly,” said Barfi. “And then they’ll start torturing again. They didn’t do anything to Steve. He rarely got beaten, he did not get tortured. They will now become paranoid that everyone they have there is a bunch of Israeli spies. I debriefed many of the hostages, so I know who got tortured and who didn’t. Jim Foley saw the worst tortures. He was captured very early on and was brought in later into the bigger prison. He was tortured very badly. There are two other people who have gotten really bad torture. These two people are still alive, they have not appeared in any videos. We cannot allow them to start getting paranoid—all right, listen. They’ve got a former American Soldier in there.” Barfi was referring to Peter Kassig, a former Army ranger whom ISIS would behead on Nov. 16; his death is also captured in a gruesome video released to the Internet, in which 16 other prisoners’ throats are cut and completed to beheading. “They’ll start thinking that they’re all spies …”

“The information has been under censor for the last two weeks, said Roman. “It’s just a matter of extending the current order.”

“We don’t care if it comes out in a few weeks when nobody cares,” said Barfi. “But not right now—they’ve got six left, hostages left. You can’t endanger these hostages right now.”

“All right,” said Daroff. “I’ll see if I can get ahold of Ron [Dermer].”

They were successful in having the Israeli military censor order extended. When I visited the IDC, Jonathan Davis, the VP of external relations, said to me, “It’s as if he never studied here.” Later, Davis looked me hard in the eyes and said, “In no way does the IDC have a relationship with [Israeli] government affairs.”

One day in January of this year, I met Moti Kahana, the Israeli-American negotiator, at a café in Brooklyn. He had stood me up days before in Manhattan but was apologetic and kind enough to come to where I lived. I was eager to meet him since he claimed to know people who knew people who claimed that they had the bodies of both Sotloff and Foley. Before we met I was told that Kahana is a “Syria guy,” and also that I should double-check everything he says.

Kahana flashed me a Syrian passport, and then took the lid off my coffee and began to drink it. “I’ll buy you another one,” he said.

“Where do you hold a dead body?” I asked him. / “In a box,” he said. “Where do you hold a dead animal?”

With his glasses off, Kahana looks a little like Vladimir Putin. His activities, however, are entirely humanistic, he said. His English is excellent, but it’s sprinkled with ungrammatical nuggets and a somewhat standard Israeli accent. “I don’t work for the government,” he said. “Make it very, very clear. I will be at the Israeli prime minister office Sunday—this Sunday. I don’t work for them, but of course I talk to them ‘cause I don’t want my head to be chopped off.”

Kahana said that he works on getting Jews and Torahs out of Syria, and that he’s involved in the humanitarian effort to help Syrian refugees. “Everything I do,” he said, “I do it for Moti Kahana.”

Kahana grew up in a Druze community in Israel, as his stepfather and younger brother are both Druze. “It’s a very dangerous area the Middle East. It’s a swamp with a lot of crocodiles, and unless you grow up with those crocodiles … I don’t trust nobody. I don’t trust my wife. I don’t trust my oldest son. Welcome to the Middle East—nobody trusts nobody.”

I told Kahana that I was planning to travel to Israel in the next few days to continue reporting Sotloff’s story. “You want to talk to the person holding the body of Steven? Who claims to hold the body—Foley and Steven?”

“In Turkey,” said Kahana. “Foley is actually not that far.”

I asked him where they’d meet me. I said that I might be up to meet his people in Istanbul, but that I was nervous and likely unwilling to head anywhere near the Turkish-Syrian border. “In Istanbul it’s safer for you,” said Kahana. “They would love to pick you up. I don’t want to look for your body. I’ll make sure it’s 100 percent safe. I’m not going to lose a Jew, an American citizen.”

I asked Kahana if he had been the source for a BuzzFeed reporter who wrote in December 2014 from Antakya that middlemen in touch with ISIS had desired to sell Foley’s body for $1M. He said that he wasn’t. “I told those idiots not to get it to the media,” said Kahana. “They got it to the media. Stupid.”

“Who is this person, and what group are they in?” I asked. “ISIS? Jabhat al-Nusra?”

“He’s in between,” said Kahana. “The person holding the body. He’s very high-level opposition. Very high level. And he’s doing it for the money. They can’t kill the guy a second time.”

“Have you seen Foley’s body?”

“Where do you hold a dead body?” I asked him.

“In a box,” he said. “Where do you hold a dead animal?”

Kahana’s goal is to bring back Sotloff, because he’s Jewish; not Foley. He said that he told the men who claim to have their bodies: “I’m a Jew and Israeli and I can’t help you get a Christian-American guy. Let me give you a million dollars each—3 for Steven—and don’t charge me anything for Foley because I can’t legally do it.”

He said that he raised $5M in the Jewish Community “like that,” snapping his fingers, to get Steven’s body back.

“What’s in it for you?” I asked.

“No. I’m not looking for money. Glory—I’ll be the one to bring Steven back home. I’ll be the hero. I get the glory. I want to be a politician in Israel someday. I was in business for the last 25 years, and I sold my company and now I’m working on my name as the one who gets things done.”

Kahana said that he had told Shirley Sotloff that he would do everything he could to bring the body back. He told her, “I can’t promise you that I will be successful. I promise you the Jewish people and the Israelis will do whatever it takes to bring any Jew back to burial. I promised to bring Steven back to burial in Miami. Me and every Israeli and every Jewish person, ’cause that’s what we do.”

“The Israelis didn’t know Steven was Israeli,” said Kahana. “I told them.”

Who put Barak in charge? I reached out to Barfi numerous times, and each time he said that he had no desire to comment anymore. “It’s over,” he told me in December of last year. “We just need to rebuild and move forward.”

Yet he continued in his role as the Sotloffs’ mouthpiece, commonly using plural subjects for his comments, in phrases such as “It’s very difficult for us.” And during our phone call on Dec. 29, Barfi acknowledged that he made all the decisions for the Sotloffs and acted as their spokesperson, and opened up about his personal relationship with Steven Sotloff. “I think of Steve 10 times a day,” he said. “I’m in Wisconsin today, I went to the Packers game, and I wish he would’ve been with me. I went to all kinds of sporting events with him and at times like that I think about him.”

When pressed to comment, Barfi backed off. “I don’t really. I don’t really want to be part of it. This is not about me. I don’t need to be a part of any story.”

I told him that I was aware that Sotloff had stayed with him in Detroit before he went back to Kimball Union Academy, and I asked if they had ever gone to a Lions game. “Yeah. We went to a Monday Night Football—the Lions and the Packers; the Lions and the Bears—and in 2011, the ALDS and ALCS. Steve was a huge, huge sports fan and I am too. And as I get older I just don’t have the time to follow what’s going on. When we’re together, we always go to stuff.”

I told him that I was planning to go to Israel in the coming days. I told him that I had heard that Sotloff had loved a particular shawarma place there, called Jamil’s, and asked if he had any suggestions for a place that I could visit that Sotloff enjoyed, or places that perhaps they went to together. “I don’t want to talk about anything that Steven and I did in Israel,” he said.

I backtracked to sports. “He loved the Dolphins,” said Barfi. “Dan Marino was his hero. He’d stay up in Libya all night to watch the playoffs. He did that every year. In Israel he’d stay up all night to watch the playoff games. He was a massive sports fan. It was one of the things that brought us closer together. When I was growing up—anything that was Detroit, I loved. As I got older and I lived abroad, I couldn’t watch. When I was with Steven he would tell me about what’s going on ‘cause he followed all that stuff religiously.”

I asked again about Sotloff’s trip to KUA, and that when he arrived he was in really good spirits. I asked for insight into Sotloff’s positive attitude, as he had come from Detroit with Barfi.

I told Barfi that I had heard that Sotloff just struck a chord with people, connecting to them instantaneously. “He was very close to Joey and Benny. Joey always helped him out. They were always there for each other,” he said. Then he added, “You’re a Jewish magazine—write ‘Steve was a proud Jew.’ He might have not been observant but it was very important to him.”

Forty days after Sotloff was captured, he reportedly fasted on Yom Kippur, as is tradition, by telling guards that he was feeling ill. “Remember,” said Barfi. “The other two Americans converted. [Steve’s] the only American man who didn’t convert.” Barfi was referring to Peter Kassig’s December 2013 conversion, after which he prayed five times daily and went by Adbul-Rahman; and Foley, or Abu Hamza, who converted soon after he was detained. Sotloff had in fact converted to Islam prior to his current imprisonment.

‘You’re a Jewish magazine—write “Steve was a proud Jew.” ’

Barfi said that Sotloff’s captors gave him extra blankets and extra food. Some of the guards, he said, took kindly to the prisoners. “Not the important people who came in, like the Beatles”—the name given to the British-accented ISIS captors responsible for Foley and Sotloff’s beheadings—“but the guards—if you converted they treated you differently.”

“Treated you better?” I asked.

“Yeah. Steve wasn’t willing to give up his faith for worldly pleasures to improve his horrible lot. He had a deep belief in his people and his faith and he would’ve never have given that up. Sometimes we have to conceal our faith to avoid persecution but it doesn’t mean that we’re not proud of it. All those prisoners knew he was Jewish.”

“How do you know that?” I asked him.

“Because they all told me when they came out that he told them he was Jewish. I talked to all the prisoners. We know what happened in the prison. It’s not like it’s a secret and we’re making up stories. We know what happened all the time. We know why one person was tortured and why one person wasn’t tortured. Everything is known.”

I asked Barfi to elaborate on Sotloff’s Jewish background. He mentioned that Sotloff’s grandparents were Holocaust survivors. “It was a very important part of his identity,” he said. In Israel, he said, Sotloff celebrated all of the Jewish holidays, and not just the High Holidays and Passover. He also celebrated Shavuot. I asked Barfi if they ever celebrated Jewish holidays together. Barfi said he was “quasi-observant” and said that he goes to a synagogue in Detroit every Shabbos when he is in town. “I wish I had more time to study in the yeshiva,” he said.

“There was nobody who knew Steve better than I did,” he said. “More than his parents, and they know that. He knew the worst things about me and I knew the worst things about him, and we accepted each other.”

“We spent 13 months dealing with Barak,” Art Sotloff told Tablet. “I saw who that guy was. He did this only for us, and only for Steven. He lost a brother.”

“He knew more than anyone; he knew more than Washington knew,” Shirley Sotloff said. “And he loved Steven with all of his heart.”

Whose responsibility is it to protect American journalists in conflict zones, and whose responsibility is it to save them when they are endangered?

When James Foley disappeared, Nicole Tung went into Syria, where she eventually stayed with Sotloff in December. She had an assignment there but was also seeking information about her missing colleague and friend. In all, Tung spent the three weeks in the south of Turkey trying to coordinate any information regarding Foley’s whereabouts and to potentially identify who was responsible for his kidnapping. To help to cover expenses in Antakya, Tung received some financial help from the Rory Peck Trust, an organization dedicated to supporting freelancers around the world. She said she stayed covert, not telling anybody outright that she was looking for Foley, and by shooting photos “to keep things going.” She said that people were afraid to talk and that many leads went cold. And when people did talk, their information was not always solid; sometimes they’d even demand money from the Foley family through Tung. “It was really difficult,” she said.

Tung then handed over the information she had gathered to the Foley family and to the “relevant authorities,” including two FBI personnel who had been sent to Antakya. “They just seemed like low-level officers. I was really unimpressed with them. The Foleys were really frustrated with these officers as well being sent to their house.”

By that point, GlobalPost, Foley’s employer, had hired Kroll, a private security company, to look for their missing staffer. “I wasn’t the right person,” said Tung. “I’m a journalist, I’m not a security consultant. The whole time I felt so useless because I wanted to be in Syria to try to follow a lead or something but in the end, obviously when I looked at it, it seems more detrimental by putting myself there to try to get information—I might not get anything.”

“Obviously it’s a personal quest to find your friend,” Tung said of Barfi’s mission to locate Sotloff. “It was the same for me. There’s only so much you can do. It takes so much more than one person dealing with all these threads coming in.” I was later told (not from Tung) that Barfi was also with the family of ISIS hostage Kayla Mueller in Arizona after news broke of her death.

And for his disappearance, one can easily fault Sotloff himself for choosing to enter Syria despite having full knowledge of Foley’s kidnapping, against the advice of numerous journalists and friends who counseled him about the dangers of crossing the border near Kilis, and after being told that he was on a blacklist and was accused of being a spy. Sotloff’s choice to enter Syria was no doubt a poor one. But Sotloff, a freelance journalist, was also simply doing his job—one that can be dangerous, and one that can gradually normalize a person to the surrounding chaos.

“It’s the freelancer’s conundrum taking bigger risks to beat staffers,” Foley said in 2012, right before he was taken a second time, and the last time. “I think it’s just basic laws of competition; you need to have something the staffers don’t, but in a conflict zone that means you take bigger risks: Go in sooner, stay longer, go closer.”

For his talent and bottomless dedication, Sotloff was posthumously awarded a number of accolades, including one for cross-border investigative reporting, named for the Wall Street Journal reporter Daniel Pearl, who was killed in Pakistan. He won a Citation of Courage from the Radio Television Digital News Association. He was honored at a number of memorial ceremonies, from the Miami Dolphins, to public art dedicated in his honor. And at IDC, his alma mater, a monument to fallen Israeli soldiers bears Steven Sotloff’s Hebrew name.

In September 2014, I met Ben Taub at a café in New York, and we ordered lunch. Taub had taken a RISC course with Tung and he showed me—using a fork to represent a body, and a side-order of coleslaw to represent a grenade—the proper way to protect oneself from shrapnel. He shared with me other precautions that he takes, including a ready-pak he has on hand in order to leave whenever needed, but requested that I not publish any further details, out of fear for his own safety.

For the story he wrote for The Daily Beast from Kilis—one of the final accounts of Sotloff’s life ever published—Taub was paid $450, 45 days after it was published, for 2,500+ important words. After lunch, Taub told me that he was feeling a bit jaded by journalism, vexed by the inability to maintain a balanced budget. In fact, Taub was able to travel to Turkey at the end of last summer because of the money he earned from his participation on NBC’s The Voice, and he recently published his first feature, about Jihadis, in The New Yorker.

I saw Taub, now a graduate student at Columbia, at an event held by the school’s Dart Center for Journalism & Trauma last February. Tung was there as well, and so was James Foley’s mother, Diane. We had all gathered to learn about a document titled “A Call for Global Safety Principles and Practices,” an outline of “safety principles and practices for international news organizations and the freelancers who work with them,” that had been created as a “response to the growing wave of intimidation, abduction, and killing of journalists around the world.” The document was signed by some of the largest newsgathering organizations around the world, and it signifies a first step of sorts toward creating a more supportive professional ecosystem within which both freelancers and employers can operate. But it also seems clear to me that this document, though a superficial step in the right direction, could very well be where this conversation—about freelancer safety, about the beheadings of people who populate the webpages and inky newspaper edges in our homes—ends, and will therefore change nothing.

Our collective thirst for news—for content—from celebrity gossip to coups in the Arab world long ago rendered Sotloff’s job financially untenable, as the Internet-led democratization of newsgathering was conflated with a redefinition of what is considered news, and as the big news organizations have largely melted away. There was just enough money in it to keep Sotloff going, should he be willing to incur some debt (who isn’t?). Reporting gave Sotloff a sense of his own value. “I can only imagine that Steve knew that this was the only thing that he had ever done in his life that he was really successful with,” said Scholder. “And for somebody for so many years was not successful and was told by everybody, including his father, ‘Get your shit in gear,’ I’m sure it was validating for him.”

On a recent Saturday morning, Arthur Sotloff was waiting for me on a bench outside The Original Lots of Lox, a very New York take on a Floridian deli. I had previously visited the restaurant in October last year after I got word that the Sotloffs hung out there from time to time.

We recognized each another right away and shook hands. Art introduced me to a man who was waiting to be seated also, and we shook hands. Then a lively, kind woman came out of the restaurant and gave Art a kiss on the cheek, checked in to see how he was doing. It hurt him to face me on the bench. He had a crick in his neck.

“So, what’d you find out about Steven?” Art asked me as we walked inside. “That he was a slob?”

Art, like his wife, was tired of talking about the past. He wanted to move on. “We don’t speak with Barak anymore, as of two weeks ago,” he said.

Art told me that I was more or less the only journalist he had agreed to speak with. He had canceled on Barbara Walters already at the last minute and preferred to see the other families in the press, like the Foleys, rather than his own. After his son was killed, the media camped out on his front lawn for two weeks, tracking his every move.

We both ordered coffee. We discussed splitting a lox platter, and he asked me if I prefer nova or lox. His father preferred nova, but he prefers lox. We agree to get half and half. He asked if I like onions on my lox bagel because he can remember his father’s breath after he’d eat onions; it’s why he doesn’t put onion on his lox sandwiches. Steven’s middle name “Joel” comes from his father.

Art told me that he and Steven would smoke pot together, a fact he seemed proud of because it highlights their closeness. (Art needs to smoke for health reasons, as well, he told me.)

“[Steven] told me everything,” said Art. “I enabled him all the time. Maybe too much.”

Art told me that over the past year, he and Shirley have become less angry with Obama, and they finally met with the president in Miami in early June. Art told me he put Obama on the spot. “I was very respectful, but also, I need answers. I need to know why certain things didn’t happen,” he told me. Obama did not provide him much in the way of answers, he said, though he would not go into any more detail.

I looked at Arthur’s wrist. He wore two bracelets of the 2LivesFoundation, which is founded in memory of his son, next to his Movado watch. He took one of the bracelets off and handed it to me.

We looked at photos of Steven together. He had many of them on his iPhone and iPad. I showed him one that I had, of Steven’s time in high school, in which he’s wearing an earring. Art said that he used to wear one as well, until a few years ago.

Along with the photos, Art keeps his son’s letter, which was smuggled out during his captivity, safe in his house.