Jews Gather at Sumud Freedom Camp to Support Palestinian Outpost in the West Bank

Confusion, shame, hope, eviction, love, ping-pong, and good posters in the Hebron hills

Eyal Shani arrived at Sumud Freedom Camp at midday, just as Fadhel Aamar was waking up, emerging from the shadowy cave he now inhabits. It was a hot and dusty Ramadan day, and Aamar had been up all night, chatting and eating with the Jewish American volunteers.

Two days earlier, the IDF raided the camp for the third time, confiscating five dozen mattresses, two tents, food, and water. They also slashed the camp’s banners with knives. Earlier raids ended with the detention of Mohammad Aamar, Fadhel’s son, and the confiscation of his car.

Aamar, a 55-year-old farmer, was born in the caves of Sarura, a depopulated Palestinian hamlet located 10 miles south of Hebron. But in 1997, he said, the violence of settlers from the nearby outpost of Havat Ma’on forced him and his family to relocate to the Palestinian village of Twaneh.

“They would burn our crops and our tents, and threw animal corpses and chemical substances into our wells to destroy them,” he said.

Sarura is one of 12 Palestinian communities in the South Hebron Hills evicted in late 1999 when the IDF declared the lands they sit on Firing Zone 918. Residents of the communities—estimated by the Association for Civil Rights in Israel to number 1,300—have been fighting the decision in court since 2000. Meanwhile, the army considers them seasonal farmers unworthy of compensation.

Six months ago, a coalition of Palestinian organizations and left-wing Jewish American groups decided to take up Aamar’s cause. On May 19, 300 activists arrived on the site and set up the “Sumud” Freedom Camp, Arabic for “steadfastness.” The group, which included 130 volunteers with the Center for Jewish Nonviolence, erected tents and began clearing rubble from the abandoned caves, preparing them for repopulation.

Organizers say about 200 international volunteers have worked in the camp, mostly from the United States, the United Kingdom, and Western Europe. Many of them are temporarily based in Israel as students, international aid-agency workers, or members of All That’s Left collective. Some 80 Israelis have also come to Sarura, representing groups like Combatants for Peace, Ta’ayoush, Haqel, and Free Jerusalem.

Shani, a tai chi teacher with bright blue eyes and a thin gray ponytail, had loaded his jeep with a slightly lopsided pingpong table and a rusting basketball hoop he found discarded in the dumpster of his Be’Sheva suburb. “I’m a kind of garbage collector, but one person’s garbage is another person’s treasure,” he said. Over the past four years, Shani’s visits to the Palestinian mountain community have been almost daily.

He cheered the camp dwellers up with a large box of vegetables, as well as rosemary and fig saplings, donations from the Bedouins of Laqiya.

***

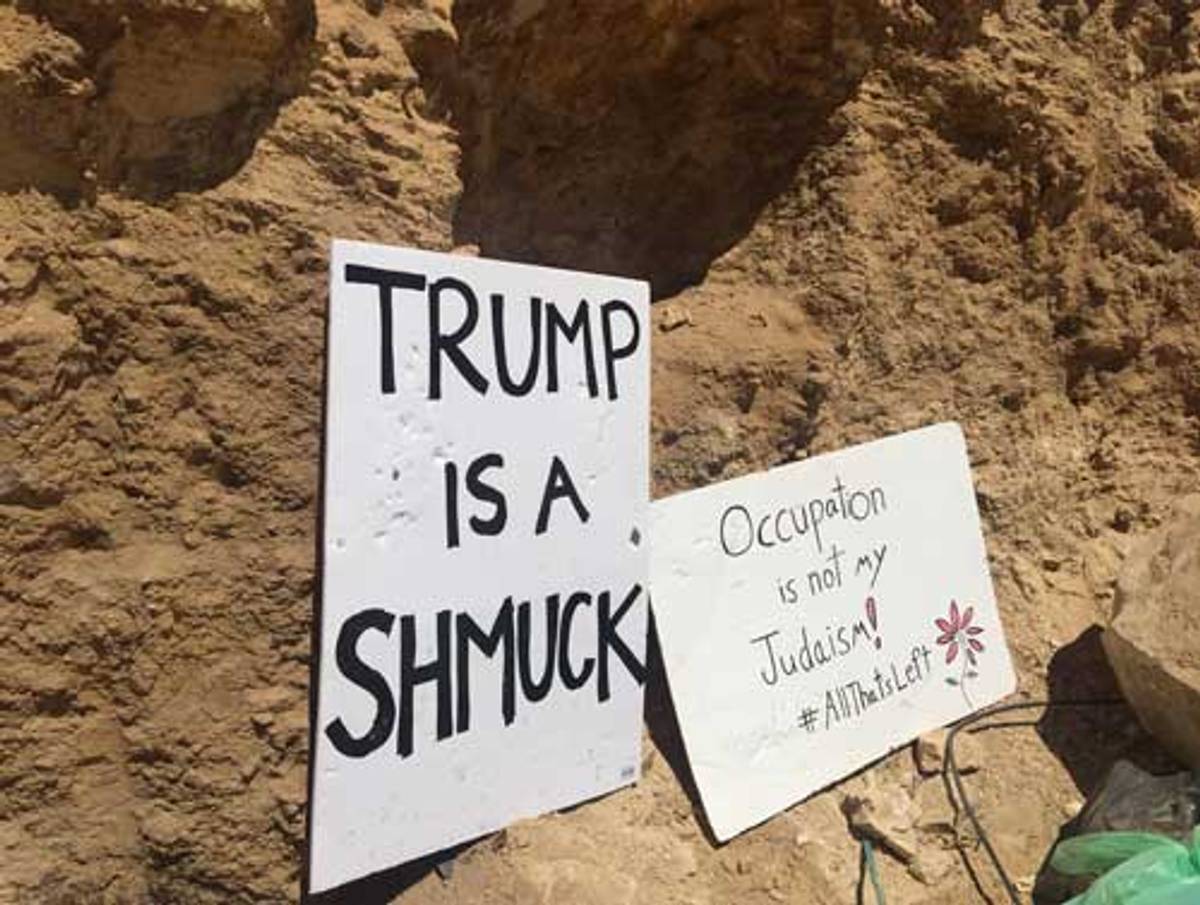

The Israeli 49-year-old was an odd man out in the camp. Its mostly English-speaking residents arrive regularly from Tel Aviv and Jerusalem for daytime and nighttime shifts, struggling at times to communicate with the local Palestinians. Three female volunteers, from the United States, Switzerland, and the U.K., began their day at Sarura cleaning up discarded water bottles and cigarette butts, trying to mend Sumud’s slashed paper banner. They lifted two handwritten placards reading “Occupation is not my Judaism” and “Trump is a Shmuck” off the ground, leaning them against the outer wall of one of the caves.

Tamar Lyssy of Basel, Switzerland, 23, helped set up the Sumud Camp on May 19 as part of the international delegation of the Center for Jewish Nonviolence. That night, a Friday, members held a traditional Kabalat Shabbat service at the site. Her parents, Jerusalem residents who sent her to Bnei Akiva as a child, supported her decision to lend a hand to the Palestinians. After graduating from sociology and Islamic studies at Brandeis University, she volunteered to help integrate Syrian and Eritrean refugees into Swiss society for a nonprofit based in Zurich. “It feels really nice to be part of this community of Palestinians, Jews, and Israelis together,” she said. “I was told this wasn’t possible, but it is, and it’s really meaningful for me to be here and see it happen.”

Natasha Westheimer was born in Melbourne, Australia, but educated in Maryland and Oxford, specializing in water management. A resident of Tel Aviv for the past three years, Westheimer came to Sarura as a member of All That’s Left. “I saw this sort of nonviolent resistance as a critical opportunity to uplift the Palestinian nonviolent movement,” she said. “As the granddaughter of Holocaust survivors, there’s no doubt in my mind that the Jewish values of justice, freedom, and equality are sacred.”

Asked why All That’s Left has to state that occupation does not reflect Judaism, Westheimer said that the State of Israel often speaks on behalf of the Jewish people and is perceived as their representative. “Living in Tel Aviv, you see the 18-year-olds getting on the train, eating McDonald’s hamburgers, changing into their bathing suits to go to the beach. These are the same people who are showing up here in uniform, destroying, demolishing, confiscating, and disrupting life,” she continued. “It’s critical for me to make the distinction between the individual soldiers and the system of military occupation.”

Dealing with Israeli soldiers as a left-wing activist has been a particularly difficult emotional process, Westheimer added. She said that acknowledging her privilege as an American Jew able to travel freely throughout the land—as opposed to the situation of the Palestinians she came to support—was a process wrought with “confusion, shame, and embarrassment.”

For Anna Roiser, who took a break from her career as a divorce lawyer in London to volunteer in Jerusalem for six months, meeting Israeli soldiers in conflictual situations has also caused some cognitive dissonance. Growing up in the Zionist religious youth movement Bnei Akiva, she never remembered discussing Israel’s policies in the West Bank and Gaza.

“Part of the problem with the discussion about Israel in the U.K. is that you’re not even supposed to talk about the occupation. The maps of Israel we had didn’t have any dotted lines; it was presented as a miracle God gave us the entire land,” she said.

“The idea of being a Zionist and supporting Israel is conflated with supporting the occupation. They’re not separable. I think that’s very problematic because then many people reject the occupation and reject Israel. It’s a great shame because I think there’s a great case to be made for Israel that is also honest.”

More worrying, perhaps, she said, was the growing detachment of Jewish students at Cambridge University, which she attended in the early 2000s, from Jewish organizations on campus. “Following the Second Intifada, there were Jewish people who didn’t like what was going on in Israel, and for that reason chose not to go to Jewish Society,” she noted. “Numbers of people attending Jewish Society would go up and down depending on what was happening in Israel.”

***

The distinction between Jews and Israelis seemed lost on Mahdi, Fadhel Aamar’s 15-year-old grandson, who was hammering away on a guitar one of the volunteers had lent him, and speaks only Arabic. “We want to get our land back from the Jews,” he said. “They move step by step to get us off the land.”

But Fadhel Aamar, who spent his entire life working as a home renovator for Jewish contractors, said his struggle to remain in the cave would surely fail without the support of the Jewish volunteers from abroad. “Netanyahu and the settlers lie to the media as though it’s a matter of Arabs attacking Jews, but God will show the truth,” he said. “These people showed my truth to the entire world. My endurance here is thanks to them.”

According to architect Alon Cohen-Lifshitz of Bimkom, an Israeli nonprofit specializing in planning rights, some 180 Bedouin and agricultural communities across the Israeli-controlled portions of the West Bank face a similar threat of eviction and relocation to Palestinian cities and suburbs.

“The shepherds of Sarura have no real alternative since this is the only land they have for sheep herding,” Cohen-Lifshitz said. “All of the state’s proposals to move shepherd communities to populated areas far from herding areas are not taken from the point of view of the shepherds but from the Israeli perspective, and are therefore doomed to fail.”

He noted that nearby Havat Ma’on, an illegal Israeli outpost supposedly dismantled by the government of Ehud Barak in 1999, continues to thrive untouched.

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Elhanan Miller (@ElhananMiller) is a Jerusalem-based reporter specializing in the Arab world.