The Israeli-American Divide

Israel fears a crisis in Egypt, but the U.S. remains calm. How did these allies come to see things so differently?

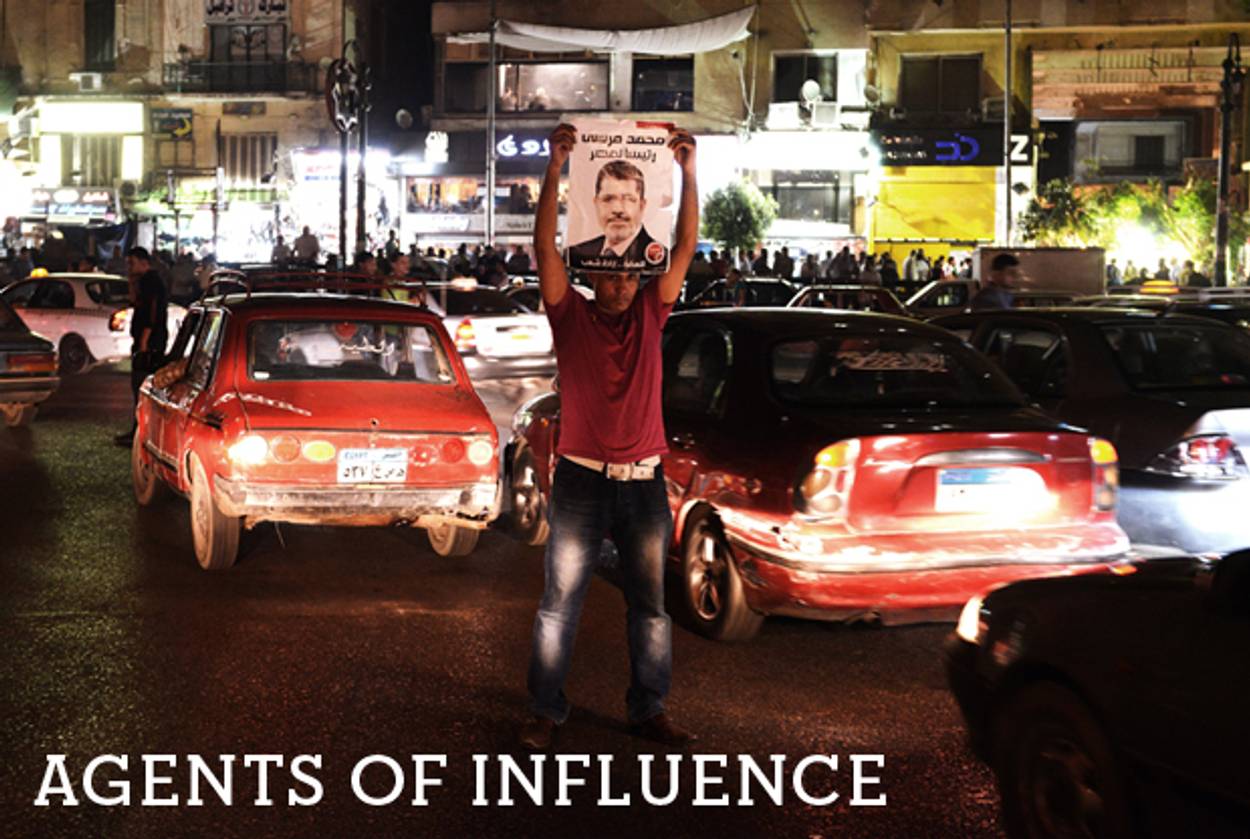

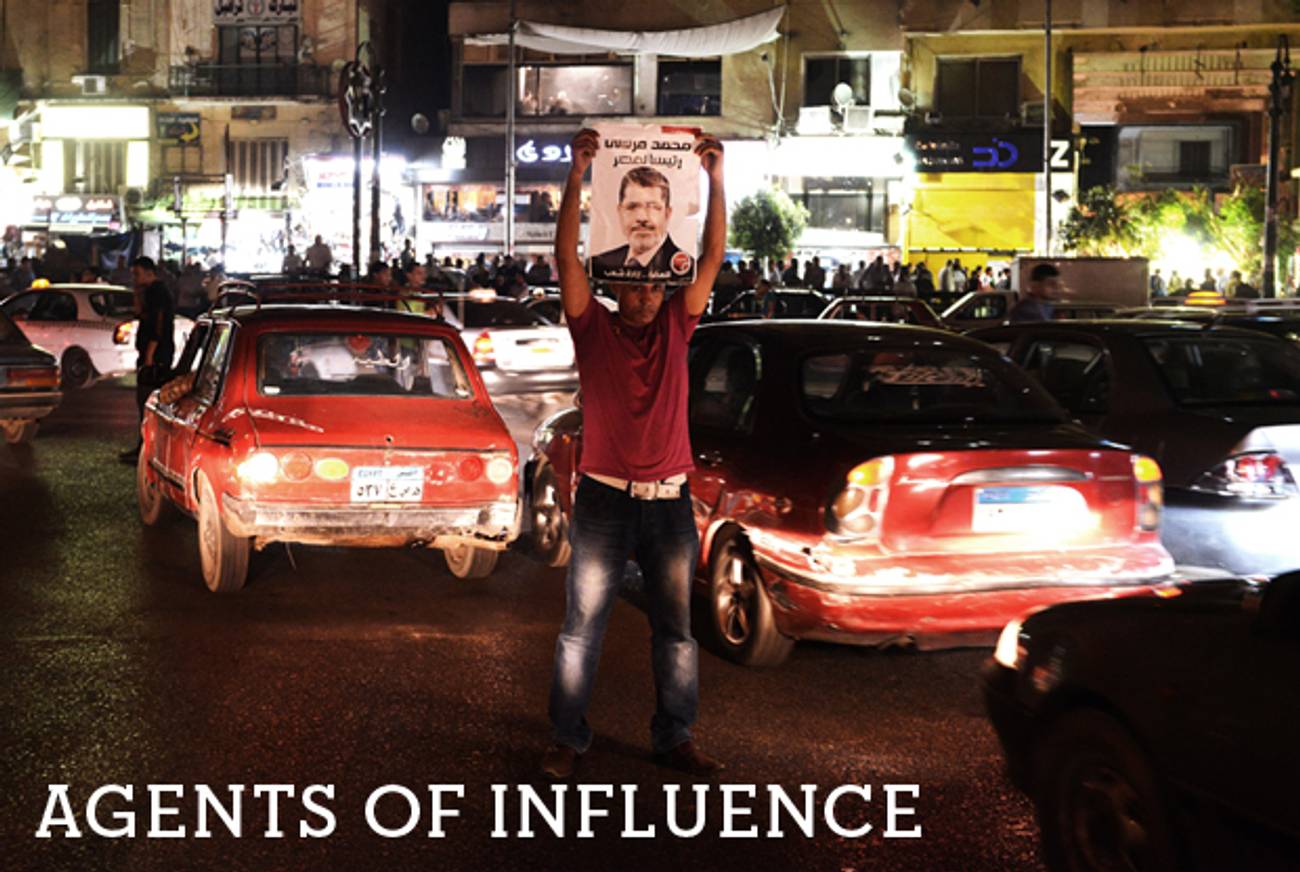

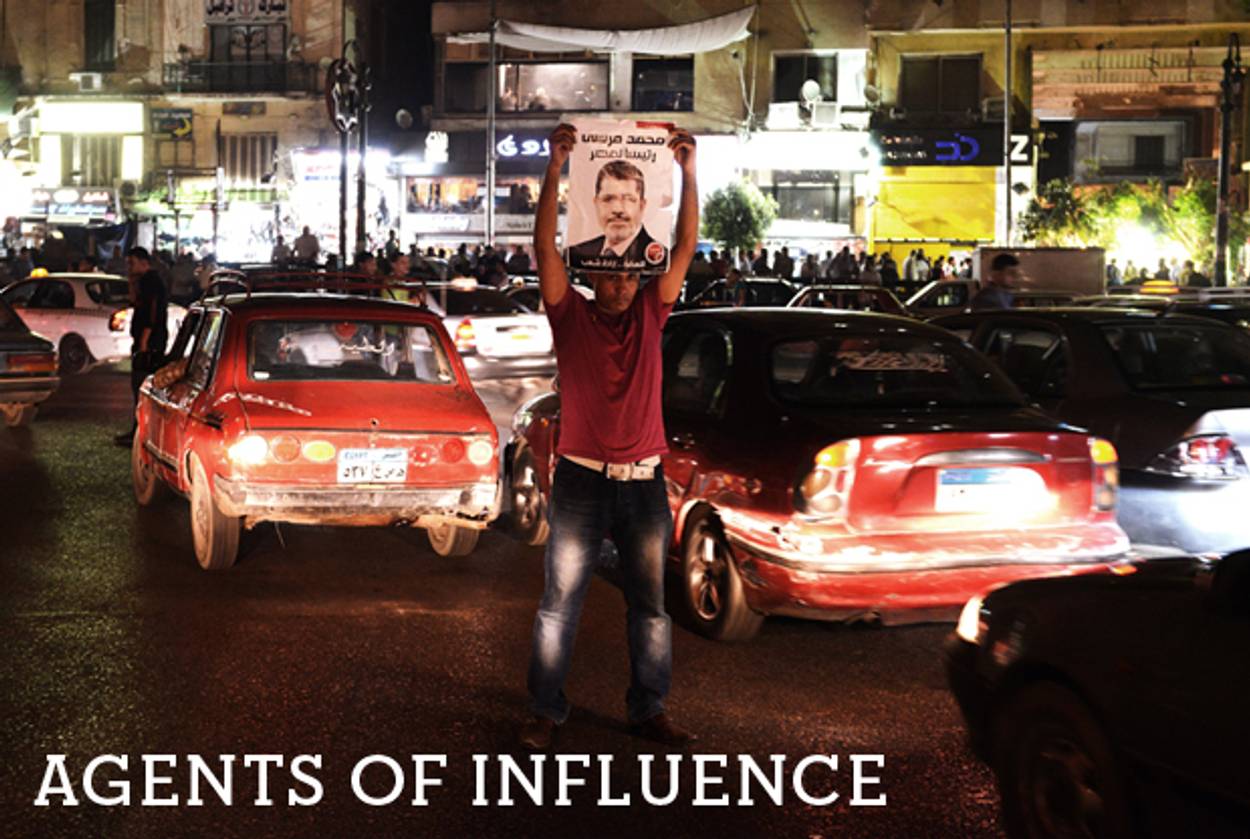

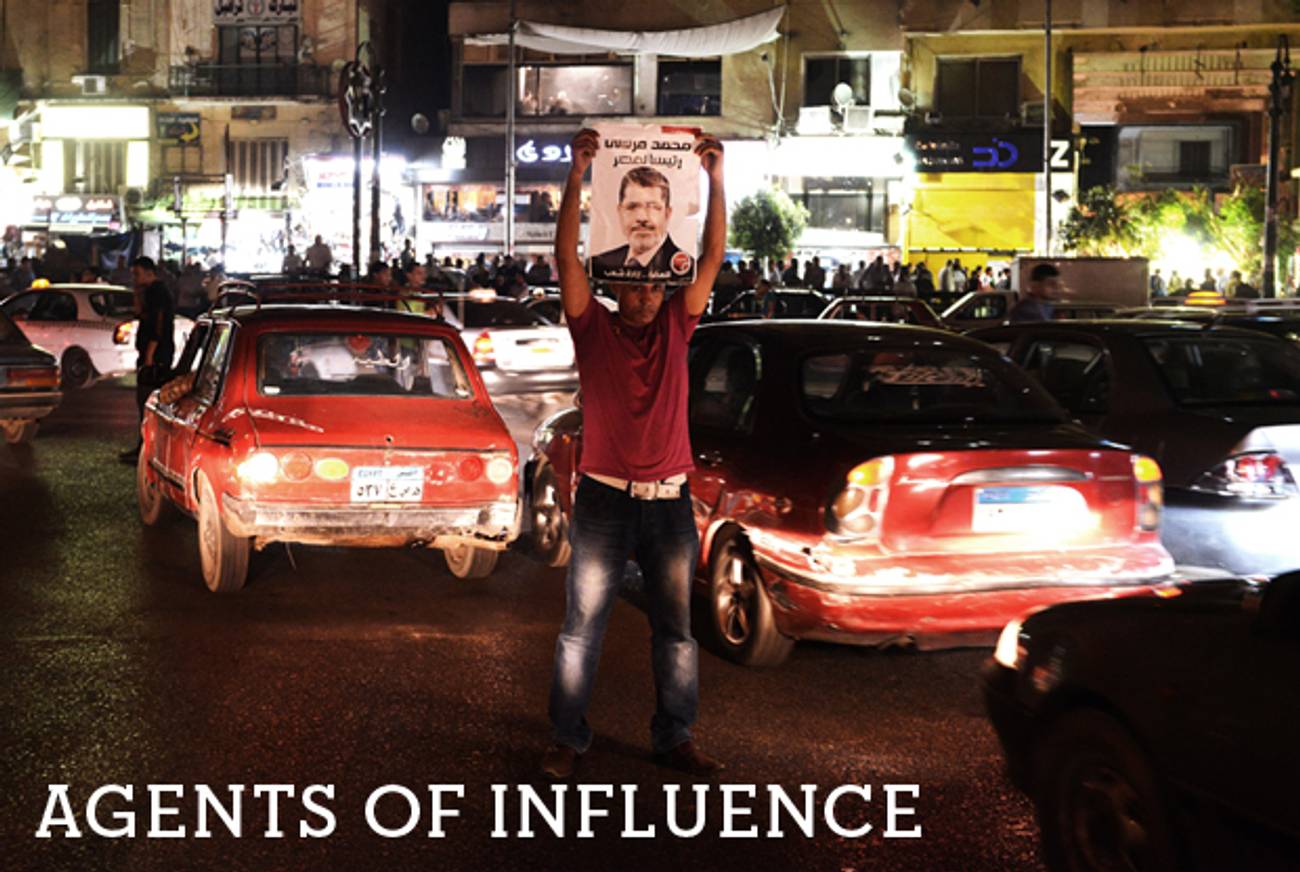

Last weekend, in the most dramatic shakeup of Egypt’s political system since Hosni Mubarak was toppled from his presidency, President Muhammad Morsi sacked Defense Minister Mohamed Hussein Tantawi, forced out Army Chief of Staff Sami Enan and other top military officials, and scrapped amendments to the constitution that limit presidential power. What a way we’ve come since 2011, when the Muslim Brotherhood promised that they weren’t even going to put forward a presidential candidate. It should come as little surprise that the founding movement of political Islam is eager to wield actual political power.

But as Cairo marches toward what seems to be a Muslim Brotherhood monopoly, the real significance of Morsi’s latest move lies elsewhere, in Washington and Jerusalem, where differing perceptions of Egypt’s political crisis have made plain that the United States and Israel are not united on matters of the Middle East. Their different interpretations of regional developments—particularly how they perceive various threats—are forcing the longtime allies apart.

Over the last six decades, the U.S.-Israel relationship has had less to do with the personal inclinations of American and Israeli leaders than with the particular events that have cemented the alliance. From the Cold War and the need to protect the vast energy resources flowing through the Persian Gulf, culminating with the attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, the strategic realities of the Middle East have kept Israel and the United States tied at the hip. That’s changing.

For Israel, everything looks like a runaway trailer truck in the rear-view mirror. From the loss of Turkey as an ally, to the prospect of chemical weapons getting loose in the middle of Syria’s civil war, to say nothing of the Iranian nuclear weapons program, Israel sees nothing but one potential crisis after another.

That’s not so for the United States. From the point of view of the Obama Administration, the Middle East is much calmer than it has been in at least a decade. American troops are out of Iraq and on their way out of Afghanistan. What has Jerusalem on edge is, from Washington’s perspective, perfectly manageable. Syrian President Bashar al-Assad is destined to be ousted without any U.S. investment; Turkey, though difficult to manage, is still a NATO ally; and it is going to be easier to deter and contain the Iranians than it was the Soviet Union. The current situation in Egypt is only the most striking illustration of the growing Israeli-American divide.

***

What Washington and Jerusalem both liked about former Egyptian president Hosni Mubarak is that he kept the most populous Arab nation from spinning out of control for a relatively cheap price and at a very important time. His predecessor, Anwar Sadat, moved Egypt out the Soviet column and into that of the United States, representing a significant Cold War win for Washington that Mubarak never tampered with.

For Jerusalem, Mubarak’s adherence to the peace treaty meant that Israel didn’t have to worry about war with its most formidable neighbor. The current Egyptian crisis, manifested less by Tantawi’s dismissal than by the growing chaos in the Sinai means that Jerusalem’s resources will be stretched thinner and thinner. Even the prospect that Egypt’s leadership may consider trying to remilitarize the Sinai is going to force Israeli strategists to reorder priorities. One immediate shift is that the Jewish state can no longer afford the luxury of devoting as much attention, manpower, and money to fighting a clandestine war with Iran and its allies as it is has for the last decade.

With Egypt much less certain to keep the peace, the equation has changed radically for Israel, but much less so for a much larger and richer United States that is no longer squared off against the Soviets. For the Obama Administration, Egypt’s hard-charging Muslim Brotherhood leadership is simply another problem to be managed in a region that is perpetually posing challenges—and this particular challenge falls somewhere in the middle range. It’s a bigger concern than, say, the political upheavals in Yemen. But it’s less of a worry than the civil war in Syria that may lead to a fragmented or even failed state, which will require the attention and resources of the international order, with Washington invariably bearing much of the burden. It’s also nowhere near as a big a deal as Iran’s drive for a nuclear weapons program. Yet neither Syria nor Iran seem to keep Obama officials up at night, so don’t expect the White House to get too worked up over Egypt.

***

If the notion that American and Israeli officials don’t see the Middle East similarly right now seems surprising, that’s in part because it follows a period during which relations between the two countries were arguably closer than they’d ever been. That mutual perspective was less a function of natural emotional attachment than the fact that in the wake of Sept. 11, 2001, George W. Bush believed that the United States and Israel faced the same, perhaps existential, threat.

It’s true that al-Qaida is a central part of President Obama’s foreign policy: His re-election campaign ranks killing Osama Bin Laden as the president’s chief foreign-policy achievement, and the White House says that empowering al-Qaida in Syria is one reason not to support the armed rebels taking on Assad. But al-Qaida isn’t justification for treating the Middle East as a No.1 priority—or for leaving no daylight between the United States and Israel.

Then there’s the issue that American policymakers have historically believed is the most important reason for U.S. involvement in the Middle East: to protect the free flow of oil through the Persian Gulf. That energy equation could be on the verge of changing. If all those estimates of North Dakota shale are right, we may soon replace Saudi Arabia as home of the world’s largest known reserves of oil. For more than 60 years we’ve been the guarantor of Saudi Arabia’s stability, protecting the House of Saud from the Soviets, Saddam Hussein, and Iran. If U.S. policymakers come to believe that the Persian Gulf is no longer a vital American interest, then it makes sense to draw down our presence in the Gulf and throughout the region. Israel does not enjoy that luxury. The Israelis are there to stay.

The reality is that contrary to what many pro-Israel advocates and those opposed to America’s special relationship with the Jewish state argue, protecting Israel has never been a vital U.S. interest. Israel, rather, is a U.S. ally, and one whose worth is valued according to how Jerusalem can best serve American interests. This point goes right to heart of what Israeli leaders are considering right now as they are deciding whether to attack the Iranian nuclear program. Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu doesn’t want to get on the wrong side of the American president, who does not want him to attack Iran.

Indeed, with all the turmoil that Israel has undergone over the past two years, the major strategic issue is not a changing Turkey, or Syria, or Egypt, or the prospect of an Iranian nuclear weapons program. Rather it is the evident and growing divide between Israel and its superpower ally.

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Lee Smith is the author of The Consequences of Syria.

Lee Smith is the author of The Permanent Coup: How Enemies Foreign and Domestic Targeted the American President (2020).