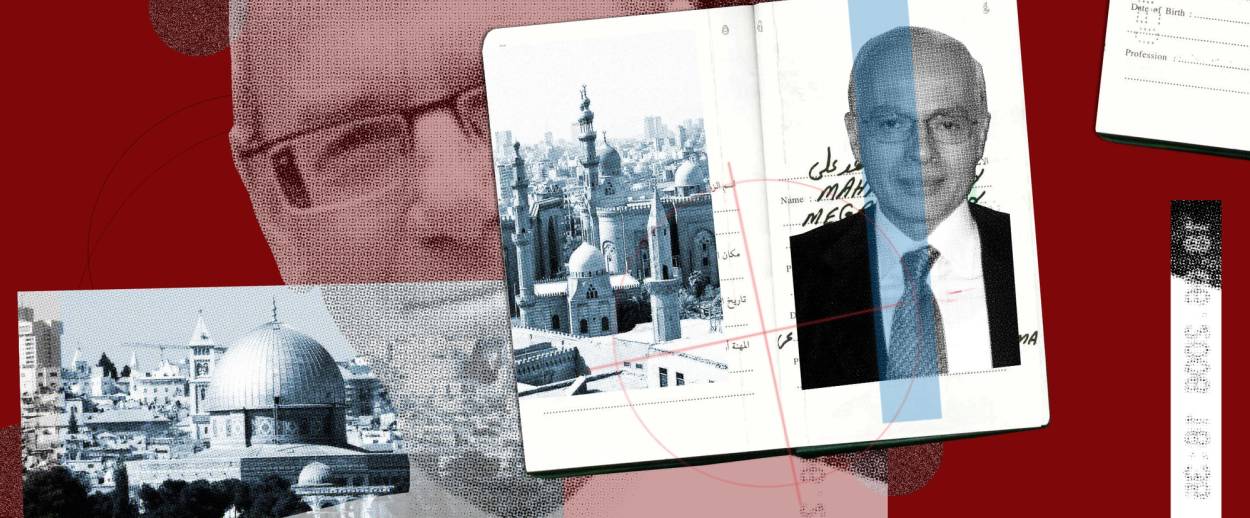

The Professor and the Spy

Ahron Bregman’s research uncovered Ashraf Marwan as an Egyptian mole and Israeli agent, which led to his apparent suicide. Now in a new book, the historian writes of his regret.

Ahron Bregman was taking a shortcut through a field on his way home from work when the shocking phone call arrived. Ashraf Marwan was dead; fallen or pushed from his London balcony.

Four and a half years earlier, Bregman, an Israeli lecturer at King’s College London and an expert on the Palestinian-Israeli conflict, had publicly exposed Marwan as Israel’s most valuable spy at the top of Egypt’s political hierarchy. It was Marwan who at the last minute tipped off Mossad, Israel’s foreign intelligence agency, on the looming Egyptian attack of Yom Kippur 1973. For Israel, that was too late.

Murder or suicide, Bregman—who was first introduced to Tablet magazine’s readers in this 2013 article about Marwan—still can’t say for sure. But his conscience will give him no rest. In a bid to “get this out of his system,” he has now published the account of his odd relationship with the man whose death he inadvertently hastened. The Spy Who Fell to Earth is dedicated to “Ashraf Marwan, who deserved a better end.”

“What at first seemed to be a moment of glory and the pinnacle of my professional career,” he writes of Marwan’s exposure, “turned out to be a sheer nightmare.”

Born in 1944, Marwan, a self-confident and extravagant chemist, was the son-in-law of Egyptian President Gamal Abdul Nasser. When his relations with Nasser soured following Egypt’s humiliating defeat to Israel in 1967, Marwan and his wife Mona relocated to London, where the young Egyptian studied for his masters degree and worked at the embassy. When Nasser died in September 1970, his son-in-law was close enough to his country’s political elite to become the confidante and special emissary of his successor, Anwar Sadat. By the end of the year he had reached out twice to the Mossad office in the British capital and was recruited as an Israeli agent, his handling overseen by Mossad Director Zvi Zamir.

In the following years Marwan would feed the Israelis invaluable information on the Egyptian army and its military strategy. He also provided details of a planned terror attack in Rome devised by Libyan dictator Muammar Qaddafi, revenge for Israel’s downing of a Libyan passenger jet that mistakenly entered Israeli airspace in February 1973. But the ultimate test of Marwan’s loyalty, that which is still debated today, would be Yom Kippur.

Bregman became obsessed with the identity of the mysterious Egyptian mole in the late 1990s, as the ugly fallout of that traumatic war continued to reverberate in Israeli public discourse. The Agranat Commission, which investigated Israel’s failure to preempt the coordinated Egyptian-Syrian strike, had placed most of the blame on military intelligence, faulting it for ignoring the many overt and covert signs of Egypt’s military buildup.

In his defense, head of military intelligence Eli Zeira deflected the blame to Mossad, claiming director Zamir had been deceived by a highly sophisticated Egyptian double agent. Why else, Zeira argued, would the spy have informed the Israelis—at the start of the holiest of days—that the Egyptian attack was to commence at 4:00 p.m. when in fact it began at 2:00? Besides, he had previously given Israel two false alarms for Egyptian assaults that never occurred.

The enmity between the two retired intelligence chiefs, now both octogenarians, continued well into the 2000s through public debates and libel accusations that were settled outside court. After all, it was their reputations and the reputations of their respective organizations that were at stake. Marwan’s name was never revealed by either man, however. That’s where Ahron Bregman came into the picture.

Bregman bought Zeira’s double-agent theory and began propagating it in his books Israel’s Wars, published in 2000, and A History of Israel, published in 2002. Lacking a “smoking gun” proving the identity of the spy as Marwan, Bregman was hoping to provoke the Egyptian to come forward.

“My plan was to raise the bar gradually, notch by notch, to try and elicit a response from him,” Bregman writes. “Should his reaction be too strong I would then have made a quick retreat and have forgotten about the business altogether.”

But Marwan’s reaction was not too strong. In fact, he didn’t respond at all. So, Bregman mailed autographed copies of his books to Marwan’s London address with the dedication “to Ashraf Marwan, Hero of Egypt.” But again, nothing.

The breakthrough came from Egypt, when in December 2002 a local reporter confronted Marwan with Bregman’s claims. Marwan responded by saying that the theory put forward by the Israeli was a “a stupid detective story.” Bregman notes the he was, “in a childish sort of way,” offended by Marwan’s out of hand dismissal of years of painstaking research. At the same time, he interpreted Marwan’s reluctance to sue him for libel as admission that he was in fact correct; Marwan was indeed the famed Egyptian spy. So, in an interview with Egyptian daily al-Ahram soon after, Bregman went all the way and asserted that Marwan was the spy previously referred to in his books simply as “the Son-in-Law.”

Bregman “felt a shiver” when he saw the interview in print, realizing there was no going back in this incredible game of chicken. But the most frightening moment came on Dec. 30, 2002, when he received a phone call at home while sweeping leaves in his garden. “I am the man you’ve written about,” said the voice on the other end, in a heavy Arabic accent.

“That’s when I realized the magnitude of what I’d done. That there was a real person there. I understood I had made a mistake.”

***

Marwan’s decision to make contact with the man who’d exposed him turned Bregman from “merely a historian whose task is to record events” to “an active participant in them,” he writes in his book. But it also had a profound psychological effect.

“Until the exposure he was in my hands. But after the exposure I was entirely in his, because I was afraid something would happen to him and he knew it,” Bregman said. “It turned me into a very fearful man.”

Marwan asked Bregman to become his adviser on the memoirs he was writing, memoirs Bregman never saw. The Israeli professor realized the book was simply a pretext to co-opt him as a source of information on developments in his story in Israel. Bregman meticulously collected Hebrew news articles on Marwan, translating them and reporting back to him on a regular basis.

On the day he died, June 27, 2007, Marwan was meant to meet Bregman in downtown London to learn about Zeira’s libel suit against Zamir, in which his name was publicly cited for the first time by an Israeli official. But the Egyptian never showed up, and Bregman headed home, to receive that devastating call.

Today Bregman believes that Marwan—who was depressed and in failing health—meticulously planned the meeting, leaving numerous messages on Bregman’s answering machine in order to mask his suicide as murder. For a Muslim, murder is more honorable than suicide and could safeguard his legacy as a double agent taken out by one of his disgruntled handlers.

“We used each other all the time, but at the end he had the final word,” Bregman said.

***

When people think of double agents they often imagine died-in-the-wool ideologues like the protagonists of Cold War-era spy novels. But in reality, spies like Ashraf Marwan are usually motivated by more mundane urges, like greed or a sense of adventure, Bregman says.

“Ashraf Marwan worked with everyone and played everyone,” he notes.

The epigraph of his book is taken from John le Carré’s 1963 novel The Spy Who Came in From the Cold:

“What do you think spies are, priests, saints, martyrs? They’re a squalid procession of vain fools, traitors, too … people who play cowboys and Indians to brighten their rotten lives.”

Bregman may identify the trait of “vain fool” in himself as well. He says that Marwan and he both shared “a reckless streak”: In Marwan’s case, it led the spy to nonchalantly arrive at meetings with his Mossad handler in London in a diplomatic car bearing Egyptian plates. In his, it caused the researcher to accuse another man of espionage without a shred of hard evidence.

“It was a game of poker and he couldn’t see my cards. It’s terrible,” Bregman says.

Nowhere in the book, though, does Bregman conclusively determine whether or not Marwan was a genuine agent for Israel. He believes that Marwan himself was undecided on the matter.

“I think we’ll never know whether Ashraf Marwan worked [only] for Israel or whether he was a double [agent]. I think he was neither here nor there. That’s the real answer. Marwan worked for everyone: The Israelis, the Egyptians, the Italians, the British. But—and this is the interesting part—when, a second before the war, the moment of truth came when he needed to decide whether he is an Egyptian or a Zionist-Israeli, he decided he’s Egyptian. That was his deception.”

Bregman will not shirk his responsibility for Marwan’s downfall but is nevertheless critical of Mossad’s mishandling of the entire case. Not only was the Israeli intelligence negligent in adequately masking Marwan’s identity from individuals within the organization, but it fell short in later safeguarding him from “predatory” researchers like Bregman who would stop at nothing to expose him.

“Once you’re in the game, you fail to see things you’re supposed to see,” he admits. “[Mossad] messed up by not coming to me, or sending a friend, to tell me I’m playing with fire. They should have informed me that while nothing will happen to me, someone else could die. That would have shaken me.”

Rather than ignore his findings, Bregman adds, Mossad should have publicly endorsed the double agent theory in order to protect Marwan from potential Egyptian assassins seeking revenge.

“They should have waited for the man to pass away and then come out and say he was a genuine Israeli spy, but we didn’t admit so earlier because we protect our people. Instead, they allowed researchers to doubt Marwan.”

Today, when Bregman discusses his tragic brush with espionage, he normally gives two pieces of advice.

“I tell people: ‘Don’t be a spy because there will always be a Bregman who tries to expose you. But if you’re a Bregman, don’t expose. The end is usually bad.’”

***

You can help support Tablet’s unique brand of Jewish journalism. Click here to donate today.

Elhanan Miller (@ElhananMiller) is a Jerusalem-based reporter specializing in the Arab world.