Trying on an IDF Uniform

While my friends interned on Capitol Hill, I learned to shoot an M-16 and ate kosher Spam in the Israeli army

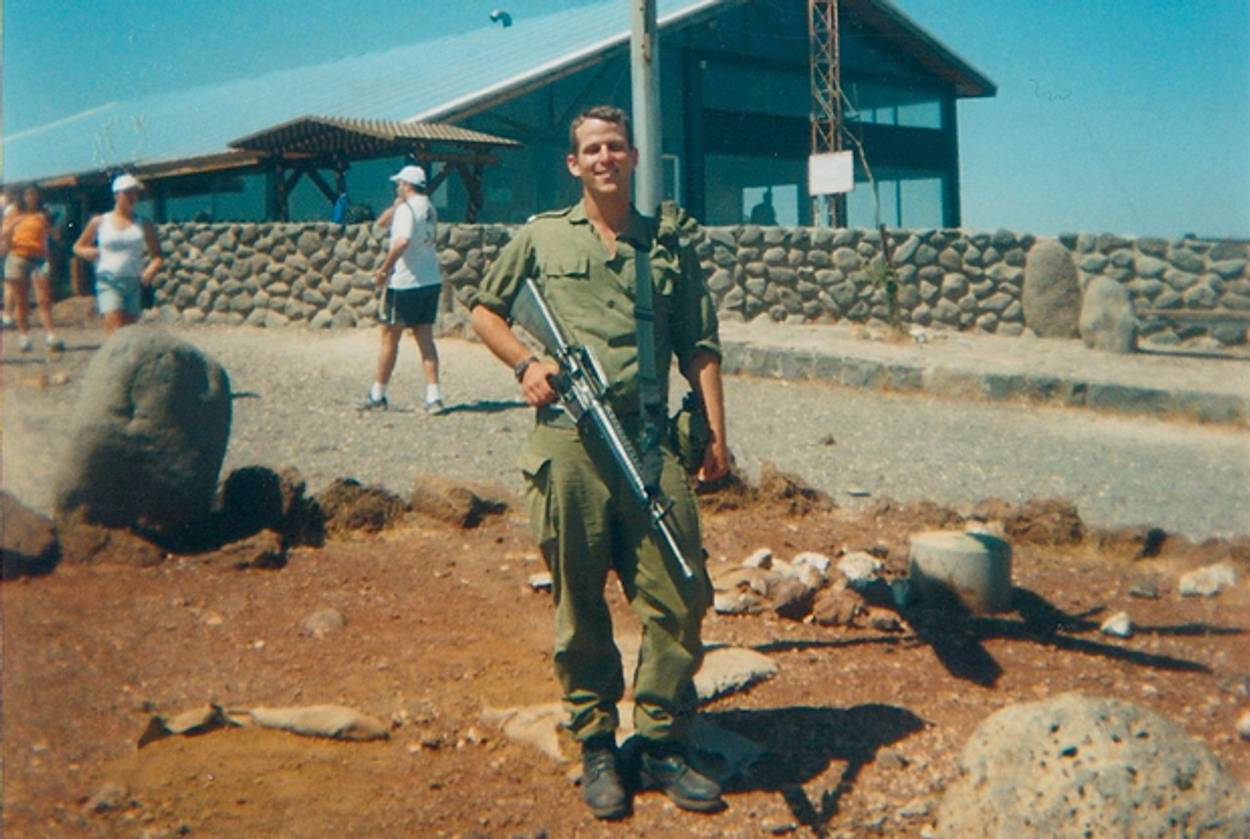

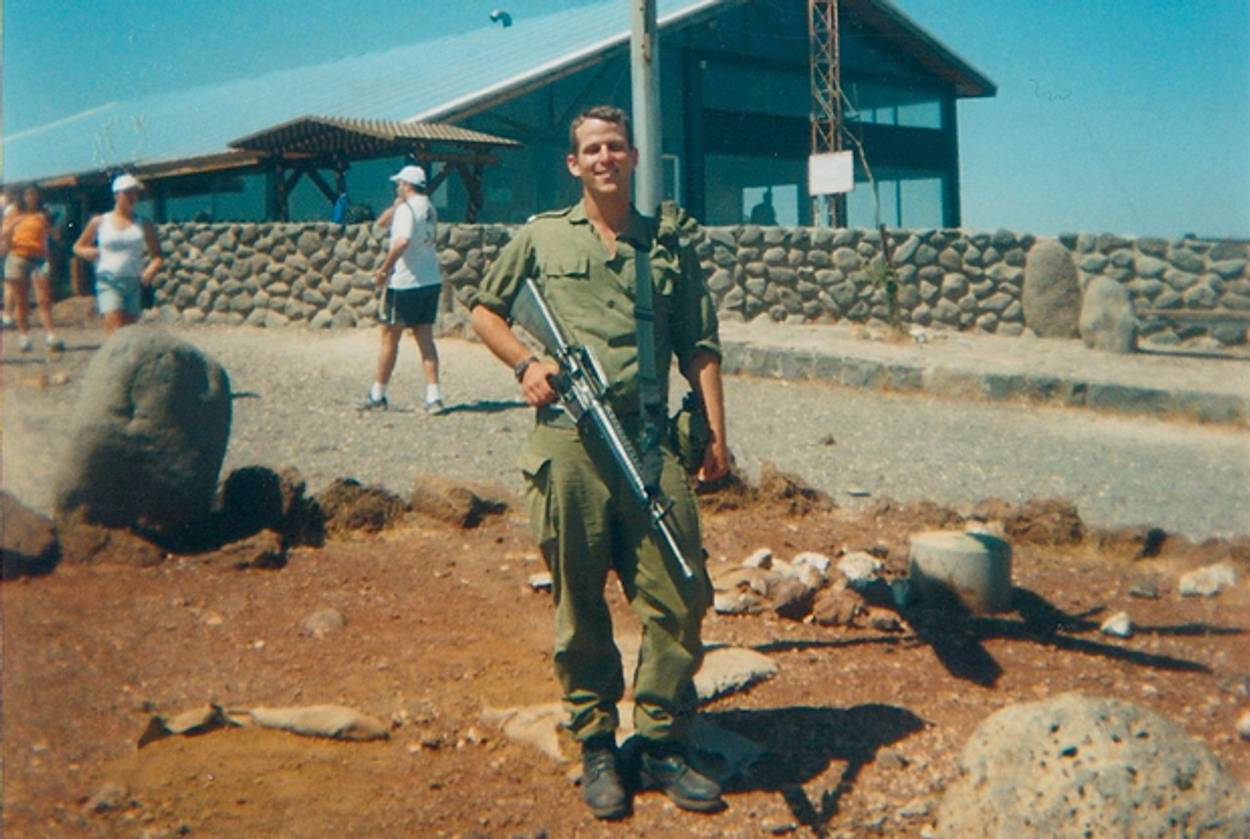

In June of 2003, the summer before my junior year of college, I entered Marva, a two-month program that simulates military service for young diaspora Jews who are curious about their mettle for life in the Israeli army. For eight blistering weeks, while my friends were scampering around Capitol Hill or staying overnight in newsrooms, I camped, crawled, and ran around the countless topographies of the land of Israel with an unloaded M-16 that I named Eve.

Despite our weapons, the musty uniforms, the boots, the tents, the bases, the food, and the unforgiving commanders, Marva still wasn’t the real army. Some had come as a masochistic form of tourism, while others, like me, felt it was the first step toward fulfilling an important duty. After all, we were cadets in the first Jewish army in 2,000 years; we were part of the body that answered for the Jewish people after centuries of silence.

I had had a difficult time explaining my decision to do Marva. Just three weeks into my freshman year, the horror of the attacks of Sept. 11, including a strike on the Pentagon just across the river from my college campus in Washington, D.C., had stunned the nation. But having spent the previous year in Israel just as the Second Intifada broke out, I had a feeling of distance and uselessness. In Israel, the threat of terror felt both immediate and existential; I’d been forbidden from taking public buses and visiting Jerusalem’s Old City because of the attacks. For a stretch near the end of the year, I wasn’t allowed to leave my dorm. As a Jewish kid raised in a very not-Jewish part of Houston, Texas, I’d never felt particularly American growing up. Israel was different; every day I seemed to be in the middle of another addictive Israeli moment. I knew Marva would only bring me more of them.

Early each morning, our unit would stand in formation in the shape of the Hebrew letter chet—the most defiant-sounding letter of the Hebrew alphabet—and together we would raise the flag. In our chet, I was flanked by Jews from Canada, France, Great Britain, Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, Morocco, Mexico, Curacao, and Columbia. We were Sephardic and Ashkenazic, secular and religious, left-wing, right-wing, gay, straight, male, and female. Jews from all over, our own mini-state.

Naturally, whenever we screwed up any order or protocol or left our sacred chet misshaped or incomplete, our commanders really gave it to us: vomit-inducing sprints through the heat, palm-gnarling push-ups on the scorching gravel, stripping us of precious weekend leave time.

While our base was in Sde Boker, mere dunams from the quiet desert grave of David Ben-Gurion, we spent weeks away in different parts of the country, studying the terrain, learning about the different units of the army. We went on marches through desert, mountain, and maktesh carrying stretchers, equipment, fellow cadets, and of course, our M-16s, as faux-guardians of our homeland. We spent a week in the field without showers and bathrooms, eating kosher Spam out of boxed rations and practicing camouflage tactics and nighttime raids. Our commanders taught us navigation skills and Krav Maga, we ran obstacle courses, sat through hours-long lectures, fired all kinds of guns, and staged fake ambushes. Our skin grew copper in hue, we began to walk with a shoulders-back swagger. We’d become Sabras.

One week we went through Jerusalem, marching in small lines through Yad Vashem and toeing around the plots at Har Herzl. At the Western Wall, tourists asked to take pictures with us. For the first time ever, cabbies and merchants didn’t hassle me. Israelis let us to the front of line at the shops and market stands, old women gave us cold grapes on the street. When we left for weekend leave, we’d hop on the buses for free and other riders would give up their seats. In other words, we had many of the perks of IDF service, but almost none of the dangers. But what kept us from feeling like we were in a militant form of Jewish summer camp was the heavy context of our experience.

***

A few days before the program began, I flew to Israel from Washington. From the airport, I made my way to Jerusalem to stay with an old youth group friend from the States who had made aliyah and was now serving in the army. Reorienting myself, I stopped for my first shawarma in years and wandered the spindly streets of the lush German Colony until I found her apartment building. I knocked on her door and she tried to welcome me, but seemed overcome. I asked her what was wrong.

While I had been in the air, she told me, a suicide bomber had struck a bus near the shuk in Jerusalem. “One of the 17 killed in the piguah,” she told me, transposing the Hebrew word for bombing, “was the mother of one of my girlfriends from the army.” Together we waited on her roommate—who also served in the army with the daughter of the victim—to come back to the apartment. Choking back her grief, she told me they have not seen each other since they heard the news.

In the weeks that followed, I would read about the bombing compulsively. It was 5:30 on a Wednesday afternoon near the sprawling market in Central Jerusalem, and the #14-Aleph Egged bus was packed with people. The suicide bomber, a 17-year-old boy who was the youngest of his siblings and the ninth recruited in a West Bank cell by Hamas, had dressed up as an ultra-Orthodox Jew, donning a heavy black coat in the middle of June to cover the device. He boarded the bus, which runs across Jerusalem, and then detonated himself a few blocks later on Jaffa Road, one of the city’s main thoroughfares.

While we waited, my friend showed me pictures of her life in the real army, the aggressive Israeli boys in pursuit of her, and she giggled at a few past conquests. She had fully acculturated to Israeli life. In that olive darkened way, she dressed and looked more Israeli than American, and her Hebrew was better than her English. She listened intently to stories about my fratty college endeavors in the country that she left behind.

We figured out that I would be on leave from Marva for her 21st birthday, something that cheered her up. In a country where the drinking age is 18, none of her Israeli counterparts understand the American tradition of excessive drinking that accompanies the 21st birthday. It’s a rite of passage she didn’t leave behind. We laughed about that. We almost forgot that something unspeakable has happened.

Such unspeakable things: After the Egged bus on the 14-Aleph route exploded on the middle of rush hour, the area was cleared because in the past, second and sometimes third explosions have followed the first, in attempts to maim ambulance workers and other first responders. Then the wounded were treated for burns, fragments of metal, which are packed into the device to cause maximum civilian fatalities, were removed from the bodies. The head of the bomber was found separated from his body. Sometimes, after bombings, cell phones ring in the pockets of the dead, panicked calls from friends and family fearing the worst. Then the bad news spreads.

As with any bombing, the bodies were identified, and the families were called. Statements were collected from witnesses and survivors. In this case, the surviving bus driver, an Arab man named Ibrahim, gave his account to authorities and Egged, the Israeli bus company.

All the scattered bits of skin were removed from the bus. They were identified so that the bodies could be buried, in accordance with Jewish ritual, as close to whole as possible. The bus was also cleansed of all evidence of the violence. The remains of the bus were transported to the bus depot in Jerusalem. Mechanics determined what could be salvaged from the wreckage. Any spare engine parts and other usable components were incorporated in the operation of other buses. Egged, in Hebrew, means linked together. All that survives is linked together.

Later, the bomber’s name was released by Hamas, which shocked and surprised his family and neighbors. His involvement in the cell was a secret. A video cassette of his last will and testament was played on Palestinian television. In the video, he was standing alone in an olive grove in front of two trees bearing the colors of Hamas, explaining his mission. He wore a green headband, his cheeks a decade away from being marked by age.

The roommate eventually arrived. In the doorway, each girl collapsed into the arms of the other and they began crying. I stayed in the other room for what seemed like hours, looking out onto Gaza Street and more or less coming to terms with the fact that on some future day I would probably decide against joining the army.

A few nights later, I was with my new unit standing in front of a bonfire overlooking a canyon in the Negev Desert. Under thousands of Jewish stars, we were called up one by one. We were told about the sanctity of our weapons. Though we will train, we were told, we hope to never use them. Our new commanders gave us each a Hebrew Bible and a gun. We were now cadets. Our commanders punched us each once—hard in the arm—to commend us on the milestone. Together, we sang the national anthem for the Jewish state, and our voices carried proudly through the canyon.

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Adam Chandler was previously a staff writer at Tablet. His work has appeared in the New York Times, the Wall Street Journal, the Atlantic, Slate, Esquire, New York, and elsewhere. He tweets @allmychandler.

Adam Chandler was previously a staff writer at Tablet. His work has appeared in the New York Times, the Wall Street Journal, the Atlantic, Slate, Esquire, New York, and elsewhere. He tweets @allmychandler.