My Father and the Jews of Iraq

On the 79th anniversary of the Farhud, a look back to Yahya Qassim and his fight for Iraqi Jews

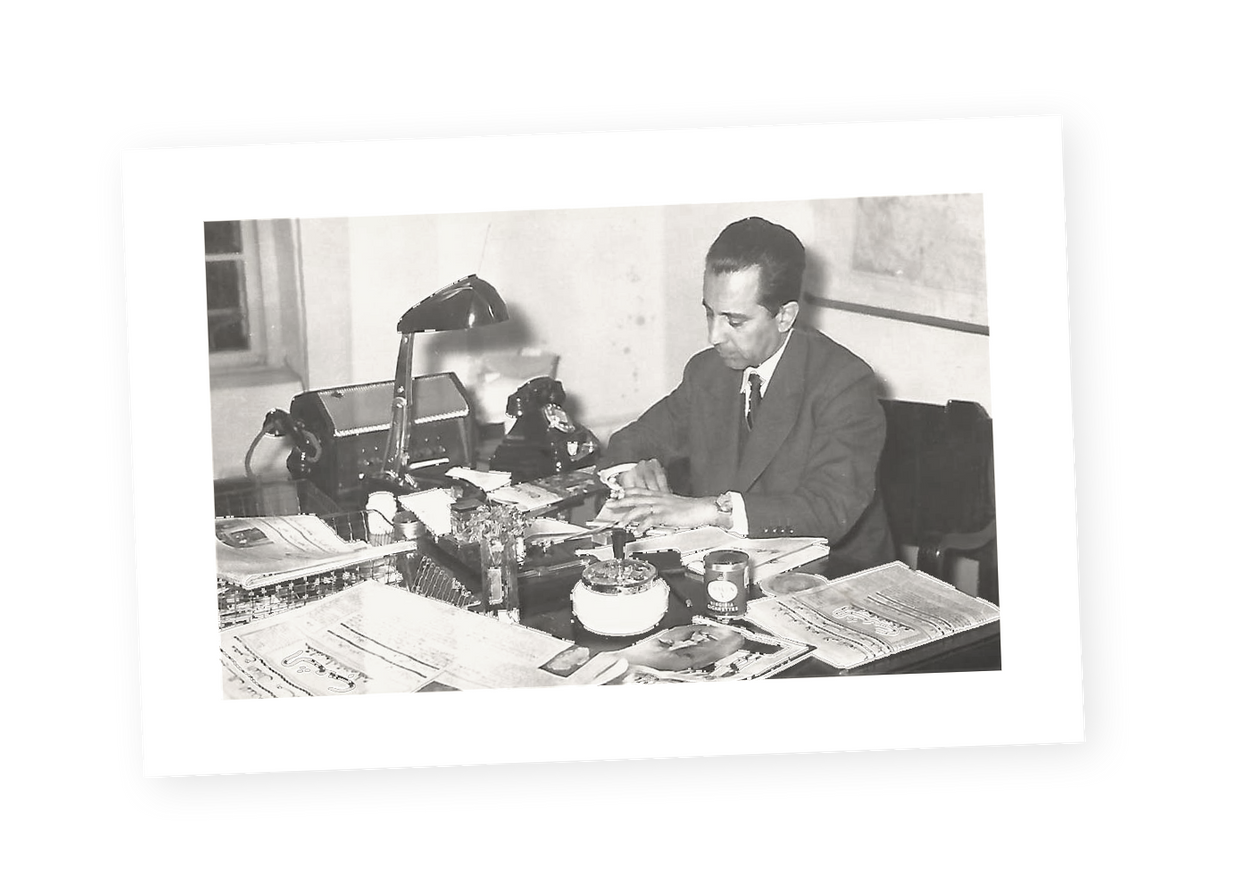

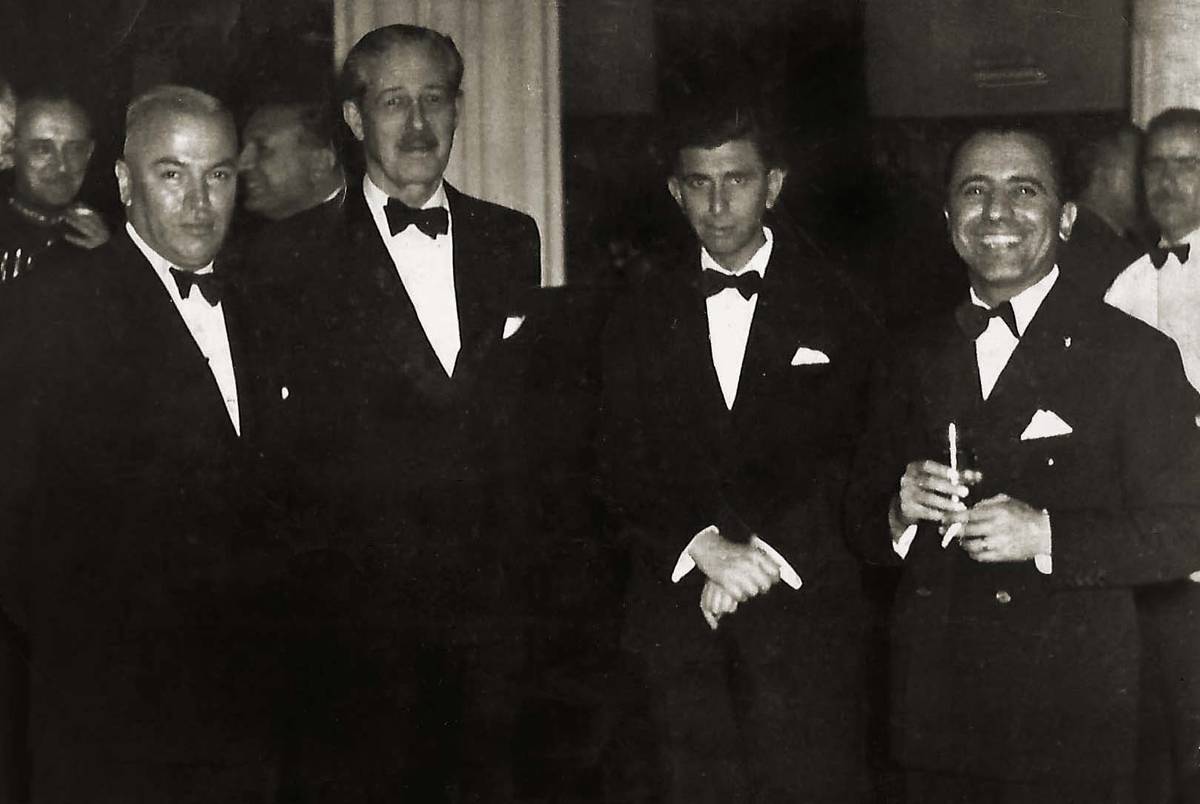

The story that I am about to tell is that of my late father, Yahya Qassim, the owner and editor of Al-Sha’b—a newspaper published from 1945 to 1958, when Iraq was under the rule of the Hashemite monarchy. The story is focused on Qassim’s defense of Iraqi Jewry in the tremendous ordeal that the Iraqi Jewish community faced immediately before and after the creation of the State of Israel in 1948. This story almost certainly would have been forgotten had it not been recounted by professor Orit Bashkin in her 2012 book New Babylonians: A History of Jews in Modern Iraq.

The Jews of Iraq occupy an important place in Judaism, as the country was home to the oldest and second-largest Jewish community in the Arab world. As with other Jewish communities in various parts of the world, Iraqi Jewry suffered from varying forms and different degrees of repression, persecution, and pogroms throughout history—spanning biblical Babylonia, the Islamic Caliphate, the Mongol invasion, the Ottoman Empire, and modern Iraq in the 20th century. Prior to discussing the events of 1947-1953 in relation to the ordeal faced by the Jewish community in Iraq at the time of the creation of the State of Israel, it is interesting to highlight the major phases of the history of the Iraqi Jewish community in the modern era.

What is known today as Iraq consisted under Ottoman rule (1533-1917) of three provinces (Wilayats in Turkish): Mosul, Baghdad, and Basra, corresponding to the northern, central, and southern regions of present day Iraq. During this period, the Jewish community in Iraq had been generally treated fairly. This was one more point in the similarity between the Ottoman and the Austrian empires: Both were multiethnic and relatively benign toward their constituent ethnicities; both entered WWI on the same (eventually) losing side along with the German Empire; and both met the same fate, namely collapse and dissolution at the end of the Great War.

The Iraqi Jewish community, along with the rest of the population in Iraq, suffered great hardships during WWI, but under the British occupation that followed, Iraqi Jews enjoyed greater security and prosperity. Then came the Hashemite Kingdom of Iraq (1921-1958). Under Hashemite rule, a pluralist Iraqi identity was created, forged, and nourished, and Jews were increasingly integrated into Iraqi society as a whole. However, this trend suffered a major interruption in April 1941, when an anti-British and pro-Nazi group of Iraqi army officers, supported by civilians, staged a coup d’etat and installed a short-lived dictatorship. Immediately after the dictatorship was ousted in late May, the Jewish communities in Baghdad and Basra suffered a pogrom at the hands of street mobs in an incident known as the Farhud (Arabic for pogrom). Rioters killed around 200 Jews and injured 1,000, raped an unknown number of Jewish women, and looted around 1,500 Jewish stores and homes. However, after the restoration of the Hashemite monarchy, the Iraqi Jewish community’s stability and prosperity not only began to recover, but also showed clear signs of growth.

Returning to the core of my story—Al-Sha’b (the people in Arabic) was launched in 1945 by Yahya Qassim with the aim of using the editorials he penned to advocate daily and emphatically for a pluralist, democratic Iraq, where citizens—whether Muslim, Christian, Jewish, or of any other set of personal faiths and beliefs—are considered fully equal under the rule of law. In less than a year, Al-Sha’b rose to become the leading newspaper in Iraq in terms of its circulation, its liberal editorial policy, and its independence from any political party or group. True to Qassim’s pluralist principles, there were several Jewish professionals working at Al-Sha’b alongside Muslims and Christians, both as journalists and in administrative positions.

In 1946, with Al-Sha’b in its second year of publication, the political atmosphere in Iraq started to grow increasingly tense in view of the expected creation of the State of Israel. Iraqi public opinion was roughly divided into three views on this matter: The first view was that of Iraqi political parties and newspapers pushing the Arab nationalist approach of considering Iraqi Jewry and Zionism as one and the same and exhibiting outright hostility toward the Jewish community in Iraq. The second view, predominant in the ruling establishment, looked at the question through a somewhat more moderate and pragmatic lens, taking into account the pressure exerted by some other Arab governments, particularly Syria’s, to follow a hard-line policy toward Zionism and the creation of the State of Israel. The third view was that of a minority, in which Yahya Qassim was a leading example. This view was embodied in Qassim’s daily editorials in Al-Sha’b, arguing that Iraqi Jews were—both de jure and de facto—fully equal to other Iraqi citizens, and that the creation of the State of Israel was a separate and distinct question of Iraqi governmental foreign policy. Furthermore, Qassim argued that sympathizing with the plight of the Palestinian Arabs in no way conflicted with the recognition of the full rights of Jews as Iraqi citizens.

In view of this division of public opinion in Iraq and the buildup to the imminent creation of the State of Israel, the position of Iraqi Jews became increasingly vulnerable to growing public pressure from Arab nationalist political forces and newspapers in Iraq, which in turn inflamed emotions and passions in various segments of society. At the same time, these Arab nationalist forces and newspapers also exerted intense pressure on the Iraqi government to adopt hostile positions toward Iraqi Jewry through the enactment of laws that were highly discriminatory, to say the least, and of questionable legality. Nor were such measures restricted to Iraqi Jews living in Iraq. For example, all Iraqi Jews living abroad were ordered to return to Iraq or risk confiscation of their property without compensation.

It is within this inflammatory atmosphere in Iraq that Yahya Qassim made his stand on a matter of principle—namely that Iraqi Jews are fully equal to Iraqis of other religions and beliefs and should be treated as such. Furthermore, Qassim argued forcefully, emphatically, and incessantly in his Al-Sha’b editorials that the questions of Zionism as a political movement along with the creation of the State of Israel, and the unquestionable full citizenship status and concomitant rights of Iraqi Jews, are separate and distinct. Qassim made these arguments daily in the pages of Al-Sha’b in direct opposition to Arab nationalist political groups and parties within Iraq, and to the chagrin of some in Iraqi governmental circles who were sympathetic to Arab nationalist views for a variety of reasons. Additionally, Qassim did not only expound his liberal views, but also acted upon them, hiring even more Iraqi Jews at Al-Sha’b for both journalistic and administative work. And last, but by no means least, Qassim took on the role of lawyer for hundreds of Iraqi Jews when the Jewish community was faced with a plethora of ad hoc governmental laws, acts, and regulations. For example, he negotiated many of the deals regarding the notorious Denationalization Law with the Iraqi government.

Alongside Qassim’s principled and successful fight for Iraqi Jewry, he continued to edit Al-Sha’b until the July 14, 1958, coup d’etat. The newly installed dictatorial regime put in place on that date banned Al-Sha’b—the only newspaper banned due to its independent editorial policy—and confiscated its presses and infrastructure. Qassim was imprisoned for several months, followed by a period of house arrest, after which he decided to leave Iraq with his family to settle in Britain (with frequent visits to the United States, and later on to Brazil). In the 1960s and ’70s, Qassim worked as a freelance writer and consultant at The Economist, The Economist Bulletin (published by the Economist Intelligence Unit), the Financial Times, the Christian Science Monitor, and the International Herald Tribune. In the 1980s, he started working on a book on the modern history of Iraq. He passed away in his sleep during a short visit to the city of Curitiba, Brazil, in 2004.

The role of Yahya Qassim in the successful and lawful emigration of Iraqi Jewry to Israel and other parts of the world, under extremely difficult circumstances, needs not to be forgotten. Therefore, it is certainly fitting that he be described posthumously by professor Orit Bashkin as “the lawyer of the community.”

Dr. Raad Yahya Qassim is a professor at the Department of Ocean Engineering at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.