A Brother’s Death

Thirty years after they joined a mob baying for Jewish blood, Yankel Rosenbaum’s killers still walk among us. So does the spirit of his brother, who sought justice.

The ceremony was brief, over in under 10 minutes. Held under cloudy twilight skies, it commemorated an event so scorched into the consciousness of the community in which it took place, and into the collective memory of New Yorkers and of American Jews, that it felt unnecessary to dwell on the details for too long.

Wednesday night marked the 30th anniversary on the Hebrew calendar of the murder of Yankel Rosenbaum, a 29-year-old Australian Ph.D. student and Orthodox Jew assaulted and stabbed at the corner of President Street and Brooklyn Avenue in Crown Heights on the night of Aug. 19, 1991. A few hours before the attack, a 7-year-old child had died after a collision with a car belonging to the motorcade of Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson, leader of the Lubavitch Hasidic movement, an accident that unleashed anger and anarchy on Jewish Crown Heights.

The Crown Heights riots are one of the most controversial and formative events in the modern history of New York, an inter- and intra-communal outburst that altered the politics and psyche of the city, and a saga packed with contradictory messages about how and why and whether vastly different groups can live together in contemporary urban America.

Wednesday night’s memorial distilled this painful and sometimes ambiguous seeming history to its essence. “Thirty years ago, an antisemitic mob screaming ‘Kill the Jew’ chased Yankel Rosenbaum through the streets,” said Rabbi and community activist Yaacov Behrman, opening the commemoration. He stood before the steel black fence surrounding St. Mark’s Episcopal Day School, the eye-catching, Moorish-style building occupying the end of a block of stately free-standing houses, of a size and spacing unusual for such a dense section of Brooklyn. Until his death in 1994, one of them had been home to Schneerson.

Rosenbaum was shoved against the fencing, savagely beaten, and then fatally stabbed not far from where Behrman stood. “Everyone here believes in racial harmony and coming together in common cause, but it is equally important not to distort history or propagate a false narrative,” Behrman continued. “Yankel was killed for being a Jew.”

Next, Rabbi Shea Hecht, a Chabad community leader who co-chaired the cross-racial Crown Heights Coalition in the years after the riots, recited the 133rd Psalm, which, Hecht told the assembled (about 50 total, split between middle-age Orthodox Jews, red-bereted members of the Guardian Angels, including Republican mayoral candidate Curtis Sliwa; and a handful of local media) “speaks about the beauty of brotherly love and unity.” It is only three verses long, and was over in the space of a few seconds.

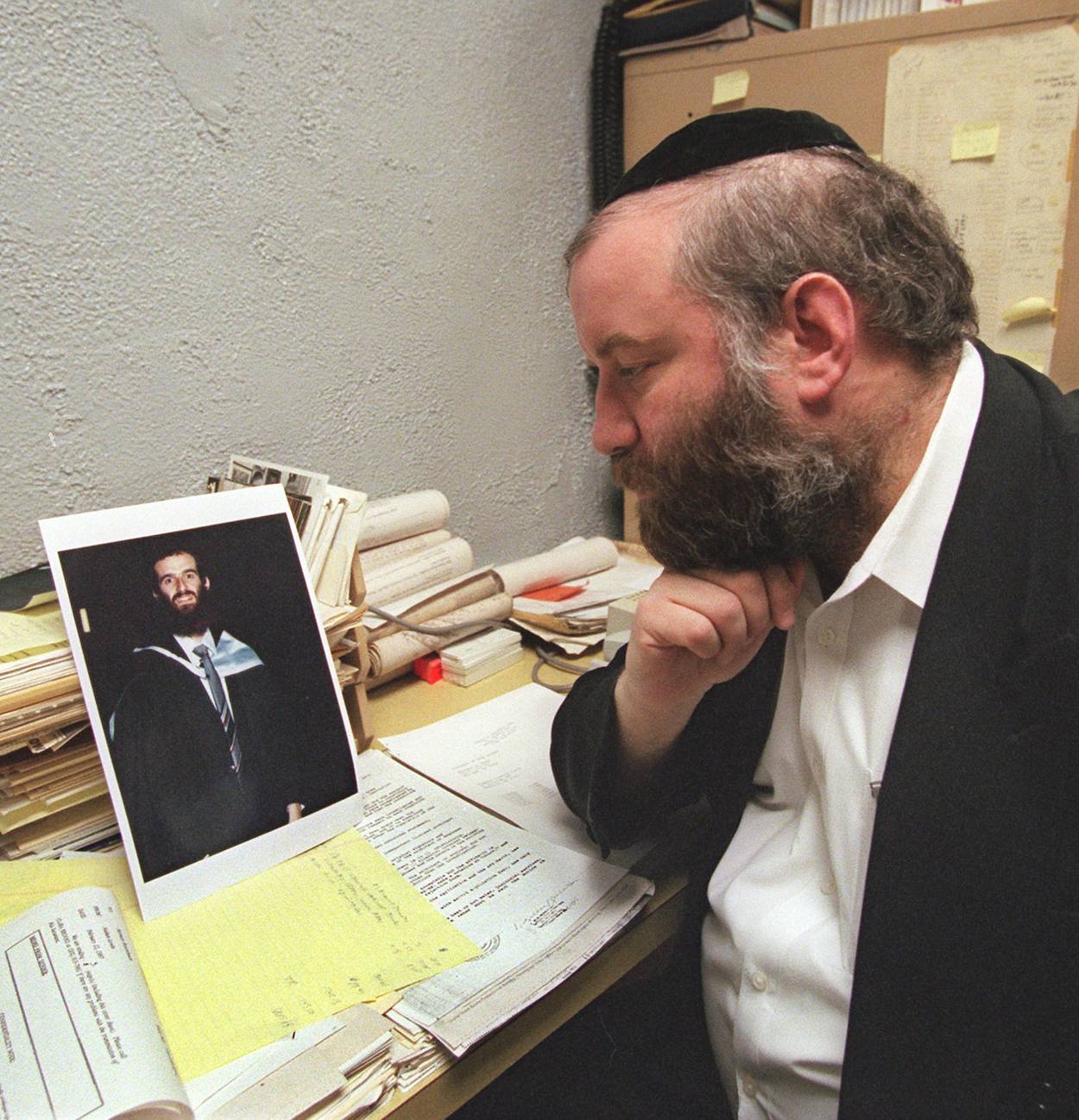

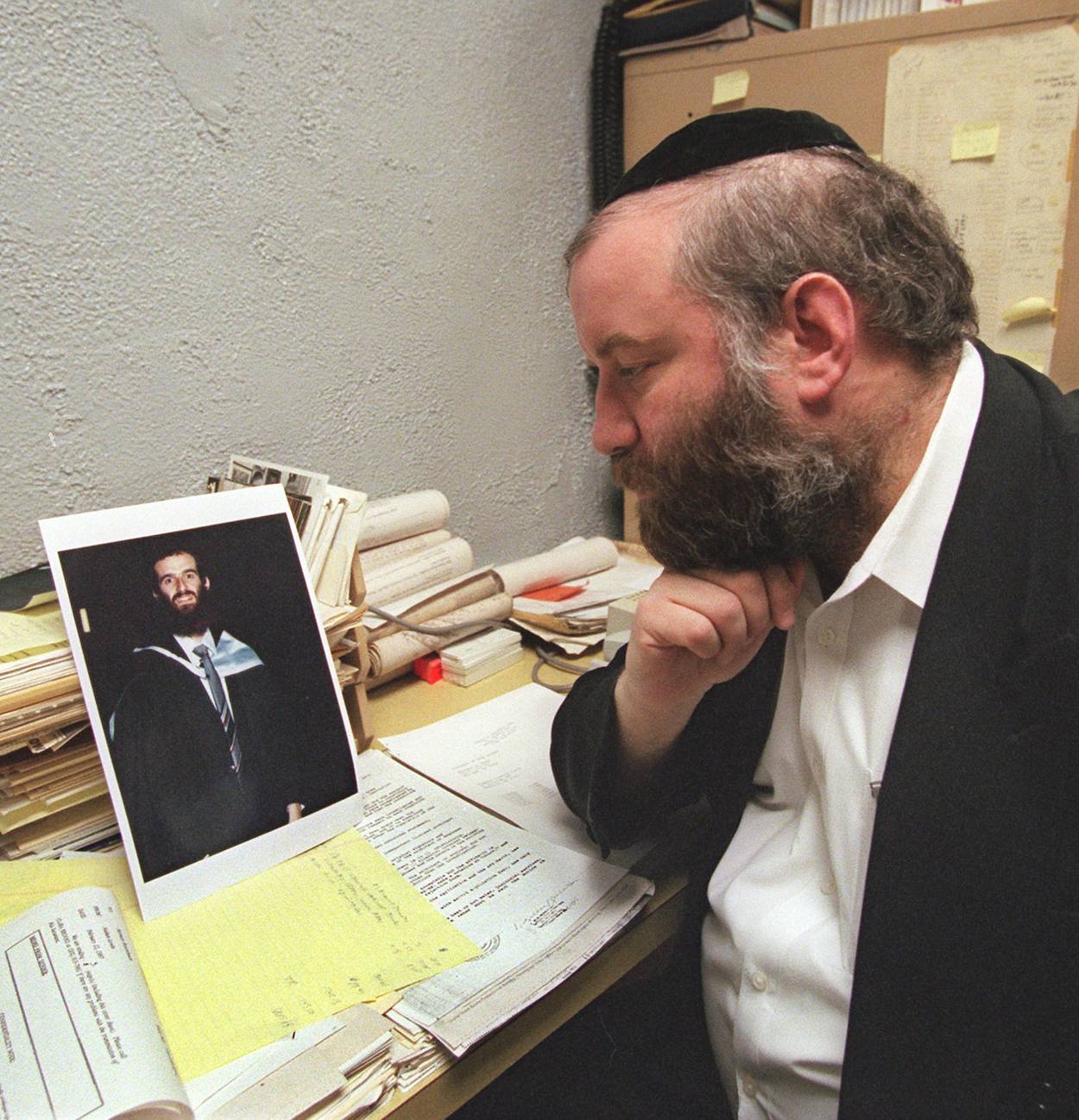

The last speaker, the person tasked with leading Kaddish, was a taller-than-average man with a short, black beard who looked to be in his late 20s. This was Yoni Rosenbaum, nephew of Yankel and son of Norman Rosenbaum, who died in his native Australia in July of 2020 at the age of 63. Norman was a lawyer who dedicated the second half of his life to insisting his brother’s murderers were brought to justice.

Yoni read a statement on behalf of his siblings, and assumedly the rest of the Rosenbaum family. “Many suggested,” Yoni began, that the Crown Heights riots “erupted” as the result of “underlying racial tensions” between Jews and the West Indian and African American community in the area. “As our father pointed out,” Yoni said, this narrative “is blatantly not true.” Instead, antisemites had used the accidental traffic death of 7-year-old Gavin Cato as an excuse for a rampage. Yankel hadn’t been caught in an intercommunal crossfire characterized by moral and factual claims of roughly equal validity. He’d been killed because of what religion and ethnicity he belonged to.

“Our father fought for justice for our uncle and Jews around the world,” Yoni said. “As our father declared so many years ago: Jewish blood is not cheap.” Moments later the ceremony concluded. Before I could even try to speak with him, Yoni was already half a block away, the site of his uncle’s murder hundreds of feet behind him. Reached by text message, Yoni directed me to a spokesperson who refused all media requests on his behalf.

Yankel Rosenbaum is, as an old friend of his put it to me, a tragically accidental part of history. At the time of his murder he did not live in Crown Heights, nor was he studying there. He did not even live in New York—he was in town to conduct research at the archive at YIVO as part of a Ph.D. thesis at the University of Melbourne about Polish Jews during the interwar period. He had been living with friends around Brooklyn, only staying in Crown Heights for at most a week or two. In one version of his killing, Rosenbaum left a barbershop just moments after a phone call came in from vigilant neighbors, advising all visible Jews that it was no longer safe for them to be out on the streets.

After Yankel’s murder, his brother Norman Rosenbaum did not live the rest of his life as if fate had selected him at random. He lived as if his purpose had always been to hold antisemites to account, and to hold to account the institutions that failed to hold antisemites to account. It was Norman who demanded that the events of 1991 didn’t fade from memory, and who worked hardest to ensure they couldn’t be distorted by politicians, radicals, communal leaders—including Jewish communal leaders eager to get past the riots as quickly as possible—or the criminal justice system. He gave fiery speeches on the steps of City Hall, and then backed up his rhetoric with years of painstaking work that often took place out of public view. “Norman was inconvenient for everybody,” as one person familiar with his work described him.

Armed with legal expertise, righteous indignation, and a growing network of political and law enforcement contacts, Norman almost single-handedly pushed for the successful federal prosecution of Lemrick Nelson, who had been acquitted of Rosenbaum’s murder after a botched state prosecution in 1992. “If it weren’t for him there wouldn’t have been a day of justice for Yankel,” said Devorah Halberstam, a prominent anti-hate crime activist whose son was murdered in a jihadist-linked shooting on the Brooklyn Bridge in 1994. “He wouldn’t let anybody shout him down. He was the person who pushed all the buttons and pulled all the plugs. He wouldn’t let this thing go away.”

As Behrman said during Wednesday’s ceremony, Norman traveled to New York from his native Australia some 250 times after his brother’s murder. “When he originally came to America his parents asked him not to sleep in Crown Heights,” Rabbi Hecht recalled to me. “Losing one son to the streets of Crown Heights, they were a little afraid.” Norman would stay with the Hechts, in Canarsie, during the first years of his campaign in New York. His specialty was in Australian tax law, but Norman did frequent pro bono consulting on a range of legal cases within the Hasidic community in New York over the years, according to Hecht, and was respected among the federal prosecutors handling his brother’s murder. “If you would tell my sons that he was a tax lawyer they would almost laugh at you,” Hecht said.

Norman was, as Hecht put it, “our spokesperson for our conscience for a period of roughly 20 years. 20 years!” A spokesperson for a community’s conscience could be described as someone with the ability to say and do things that fear or shame keeps buried within other people. That included actions that sought to reconcile the communities in Crown Heights—Norman held widely publicized meetings with members of the Cato family. His impact was measurable: He successfully pushed for new NYPD policies toward hate crimes. Nelson was sentenced to 10 years in prison in 2003, for violating Yankel Rosenbaum’s civil rights, a case that might never have been brought without Norman’s work.

But Nelson was one of perhaps as many as 20 people who attacked Yankel Rosenbaum in the moments before he was stabbed, meaning that potentially dozens responsible for his death were never charged or even arrested. Whether any amount of activism, no matter how effective, can fully restore any moral balance is a highly subjective question, one whose answer differs from person to person and from outrage to outrage, and I wondered if Norman himself had ever come to his own answer.

Was he satisfied, in the end? I asked Rabbi Hecht. Hecht says he was not—that Norman believed too many of his brother’s killers walked free for him to ever be satisfied. “This is something he said repeatedly.” But, Hecht added, “I think your question is very much on target. In the yeshiva we say, the good question is more important than the good answer. I hope you underline the question more than my answer.”

“I think he knew what he was accomplishing,” Hecht continued. “People asked him, ‘What are you coming back for?’ I heard people tell him, leave it alone. Go back to Australia. And he would say, ‘I’m fighting my battle, I’m fighting the Jewish battle, and more importantly, I’m fighting Yankel’s battle.’”

Armin Rosen is a staff writer for Tablet Magazine.