A Centuries-Old High Holiday Prayer About How Hard It Is To Pray

Making sense of a translation of Rabbi Yisrael ben Moshe Najara’s ‘Yanuv Pi,’ which proposes a solution

If you have trouble with the prayers recited on Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur, you’re not alone. Their own authors did too.

As dramatically captured in Hineni, the poignant meditation recited by the cantor before he begins to chant the High Holiday Musaf liturgy, one of the spiritual crises of the High Holidays is the overwhelming sense of awe and unworthiness when standing before the Creator. But Hineni addresses only the cantor’s anxiety in representing the congregation before God. For the deeply personal tensions which color the day, we must turn our attention to the words of other liturgical selections which acknowledge the individual’s attempts to offer meaningful words before the Creator.

One lesser-known High Holiday piyyut (devotional poem), which artfully engages in the theme of the individual’s spiritual strivings to “speak” to God on this day, is Yanuv Pi, commonly attributed to Rabbi Yisrael ben Moshe Najara, a mystic and poet who lived in the Ottoman Empire around the 16th and 17th centuries. Yanuv Pi portrays the eternal struggle—between the heart and soul, the body and the spirit—to muster up the courage and ability to pray before God. (The full text and translation of Yanuv Pi can be found at the bottom of this post.)

The opening words of the piyyut describe how every attempt to express an utterance to God is stifled by the heart’s resistance and an ensuing, overpowering fear:

My mouth expresses an utterance but my heart hardens and is overcome by great terror /

Who am I to proffer prayer before the One who gives voice to the voiceless?

The poet portrays himself as vastly inferior to even the lowest tier of angels who praise God. The tension the author feels with the angels throughout this composition is noteworthy, as Jews traditionally strive to become increasingly angel-like during the High Holiday period—through extensive praise of God, keeping our feet together during prayer (understood as an imitation of angelic appearance), and culminating on Yom Kippur, when white garments are donned and physical pleasure is eschewed.

Unlike the prayers of purely spiritual angels, however, the human soul’s strivings must contend with man’s nature as a corporeal being, a tension Najara consistently laments in this piece. To reconcile this seemingly unbridgeable divide between the soul, whose foundation is the heavens, and the physical, earth-bound body that houses it, Najara ultimately proposes a solution: The soul can intercede on behalf of the body, praying for its ability to rise up to the level of the heavens. Najara concludes his meditation by appealing to God for the resilience to overcome this spiritual crisis and the fortitude to pray to the Divine.

In terms of form, Yanuv Pi is comprised of five stanzas. The first letter of each spells out “Yisrael,” the author’s given name. In the tradition of most piyyutim, the piece draws upon a rich tapestry of biblical and rabbinic allusions with which its original audience was presumably well familiar. Today, this piyyut is used primarily in Turkish and Iraqi Jewish communities for High Holiday Musaf, a fitting bookend to the sobering Hineni reflection recited at the outset of Musaf.

As we enter the holiday season of introspection and personal growth, let’s hope we find within ourselves reservoirs of strength and focus to enable us to connect spiritually both with the Divine and with one another. And let’s hope that our prayers lead us to Najara’s sense of unity in body and soul so that we may achieve spiritual clarity and growth for ourselves, for our community, and for our world.

***

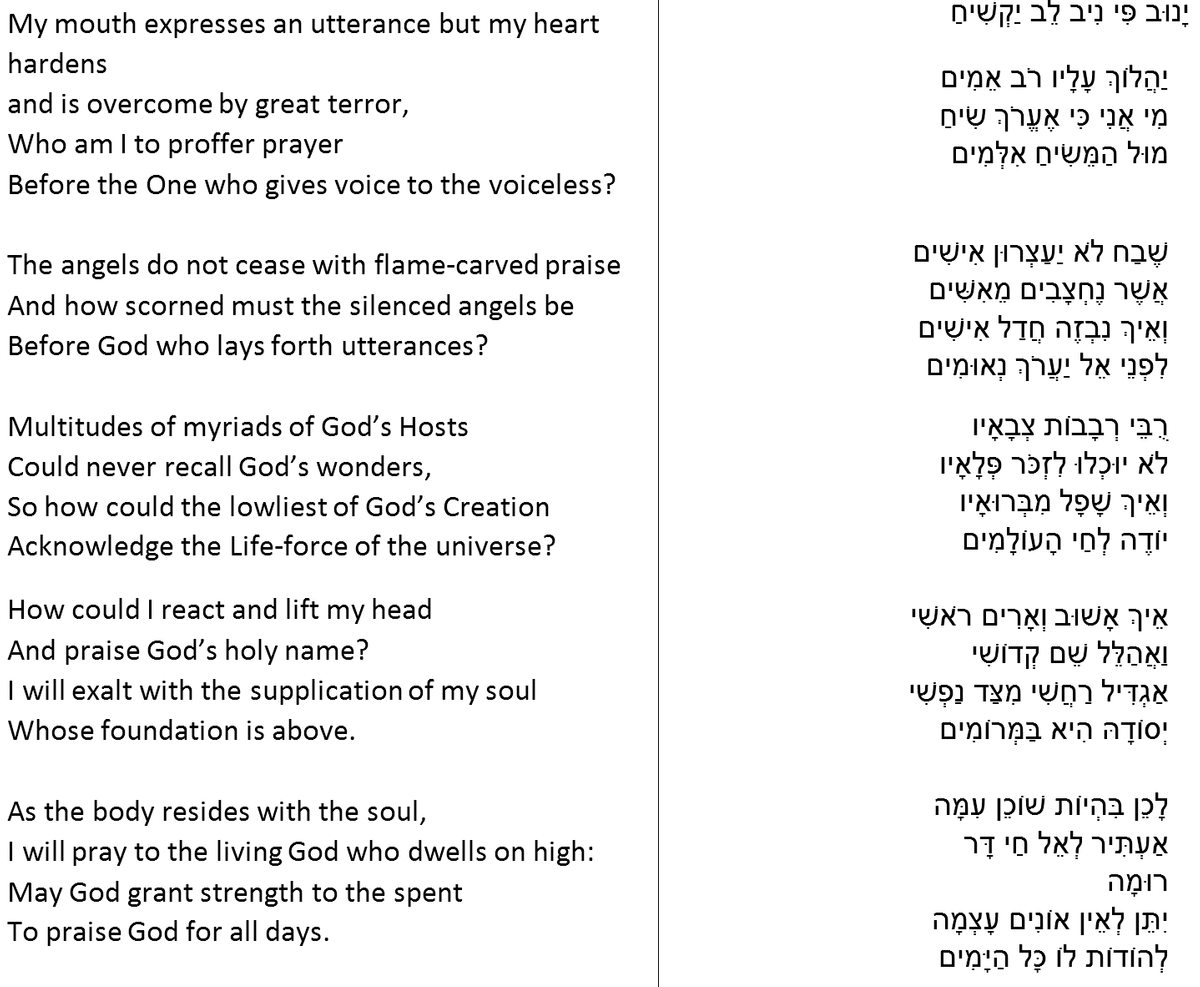

Yanuv Pi

Translation by Raysh Weiss

Rabbi Raysh Weiss is the spiritual leader of Shaar Shalom Congregation in Halifax, Nova Scotia. She holds a PhD in Cultural Studies and Comparative Literature from the University of Minnesota-Twin Cities.