A Chess Legend’s Barrier-Breaking Legacy

The chess world responds to Judit Polgar’s recently announced retirement

In 1992, after nearly two decades of living in solitude in California, former world chess champion Bobby Fischer traveled to Yugoslavia for a rematch against Boris Spassky, the Russian chess player he had defeated to win the 1972 championship. Though the match featured two all-time greats, and would be called—under Fischer’s orders—“The World Chess Championship,” it had no official bearing. The reclusive, cash-strapped Fischer would win the match (and with it $3.5 million) but he’d become a wanted man by the U.S. government by participating in an event that took place in a country against which commercial sanctions had been leveed (Fischer, who also owed 15 years of back taxes, had been forewarned but competed anyway.)

So Fischer, now a fugitive, fled to neighboring Hungary, partly to pursue 19-year-old Zita Rajcsanyi, who lived in Budapest. But he was also inspired by the advice of Susan Polgar, then a 23-year-old chess grandmaster, and the oldest of three chess-playing sisters from a Hungarian Jewish family, who suggested that Fischer come to Budapest and enjoy its wealth of culture and prodigious chess talent. Chief among them would be the Polgar sisters, Susan, Sofia, and Judit, described by Frank Brady, author of the Fischer biography Endgame, as “the royal chess family of Hungary.”

Their father, chess teacher Laszlo Polgar, managed his daughters’ careers, and had them training diligently from a young age. As chess journalist Howard Goldowsky explained via email, “Before there was Malcolm Gladwell and his promotion of the 10,000-hour “rule,” there was Lazlo Polgar and his geniuses-are-made-not-born “rule.””

While Fischer would spend the rest of his life spewing vitriol in exile, first in the Philippines and Japan, and finally in Iceland where he was granted asylum, the Polgar sisters have each enjoyed remarkable runs of success at the chessboard, breaking numerous professional records, and shattering gender norms along the way.

Susan, the eldest of the Polgar sisters, was introduced to chess at the age of three, published her first chess puzzle at four, and became an international grandmaster by the age of 15. She was ranked as one of the top female chess players in the world for 23 years, winning four consecutive Women’s World Championships and ten medals (five of them gold) as a member of the Hungarian Olympiad team. She’s now the coach of the No. 1-ranked Webster University chess team, and this year was awarded the Furman Symeon medal, a World Chess Federation (FIDE) accolade for the best chess coach who mentors both men and women players.

Sofia, the middle child, was also a chess prodigy, best known for her success as a 14-year-old at the 1989 Magistrali di Roma tournament, where she dominated an all-male field, including four grandmasters. “The Sack of Rome,” as her performance has been called, ranks as one of the strongest in history.

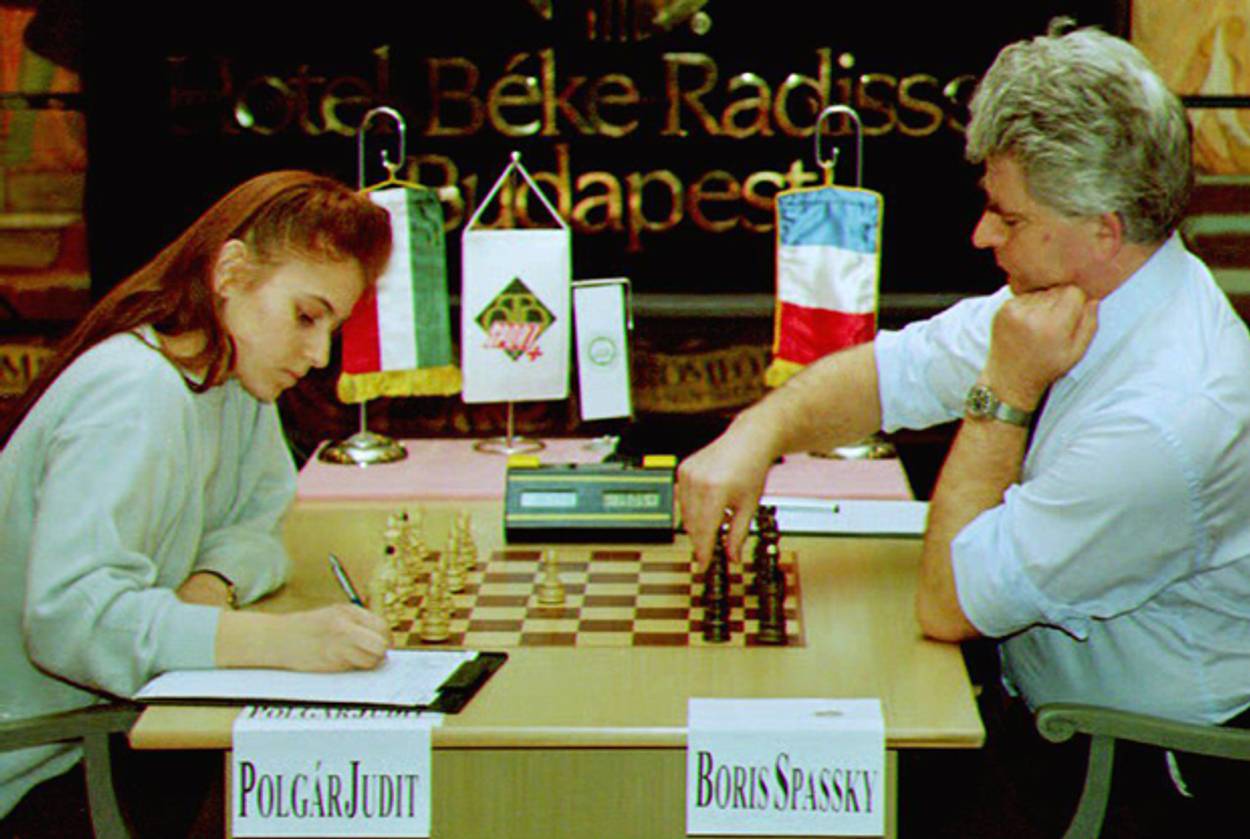

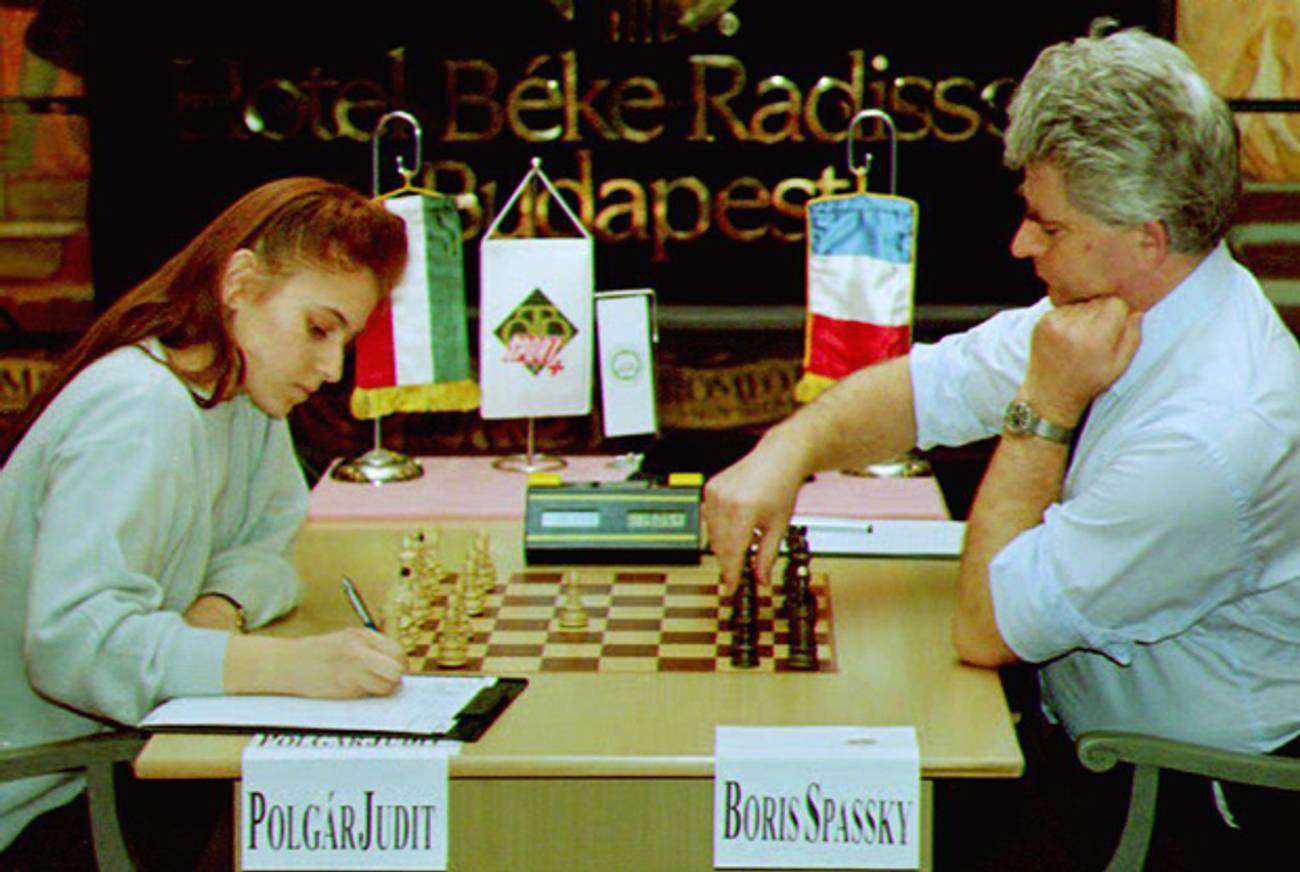

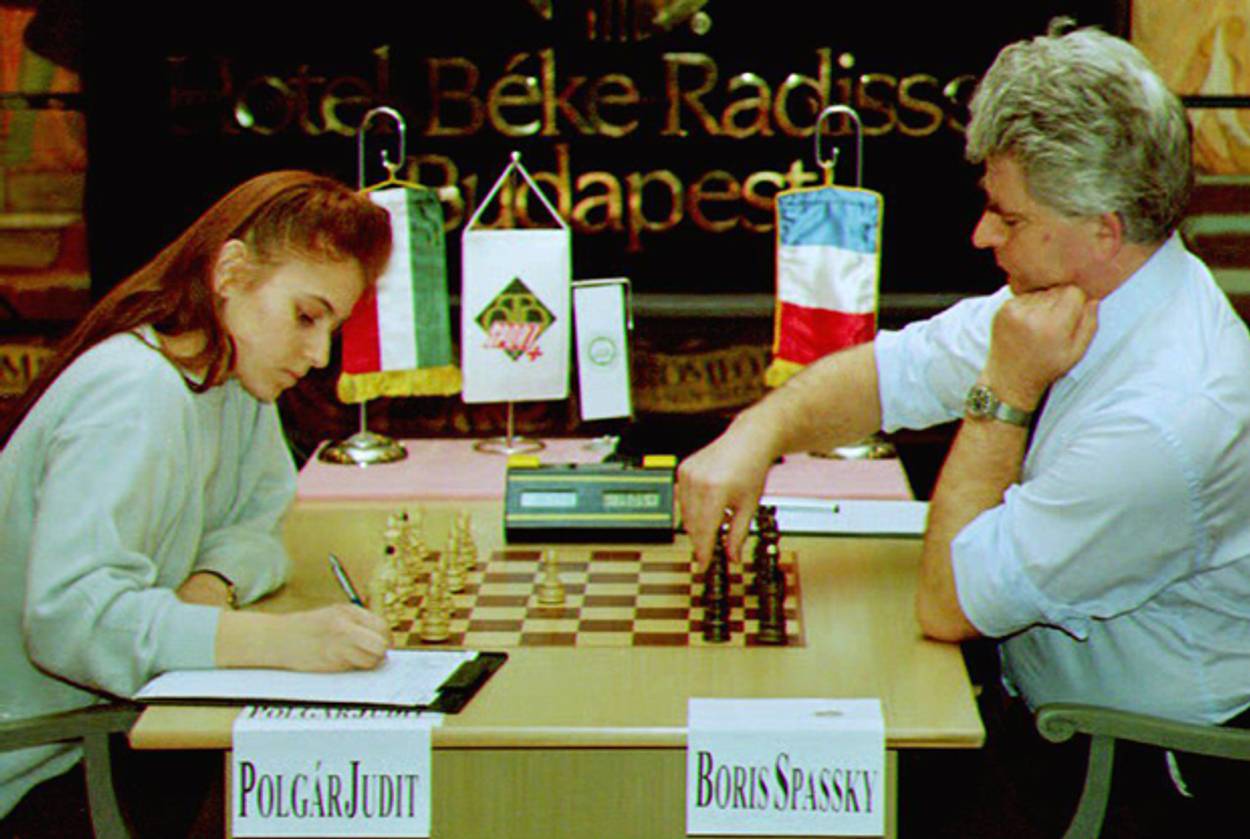

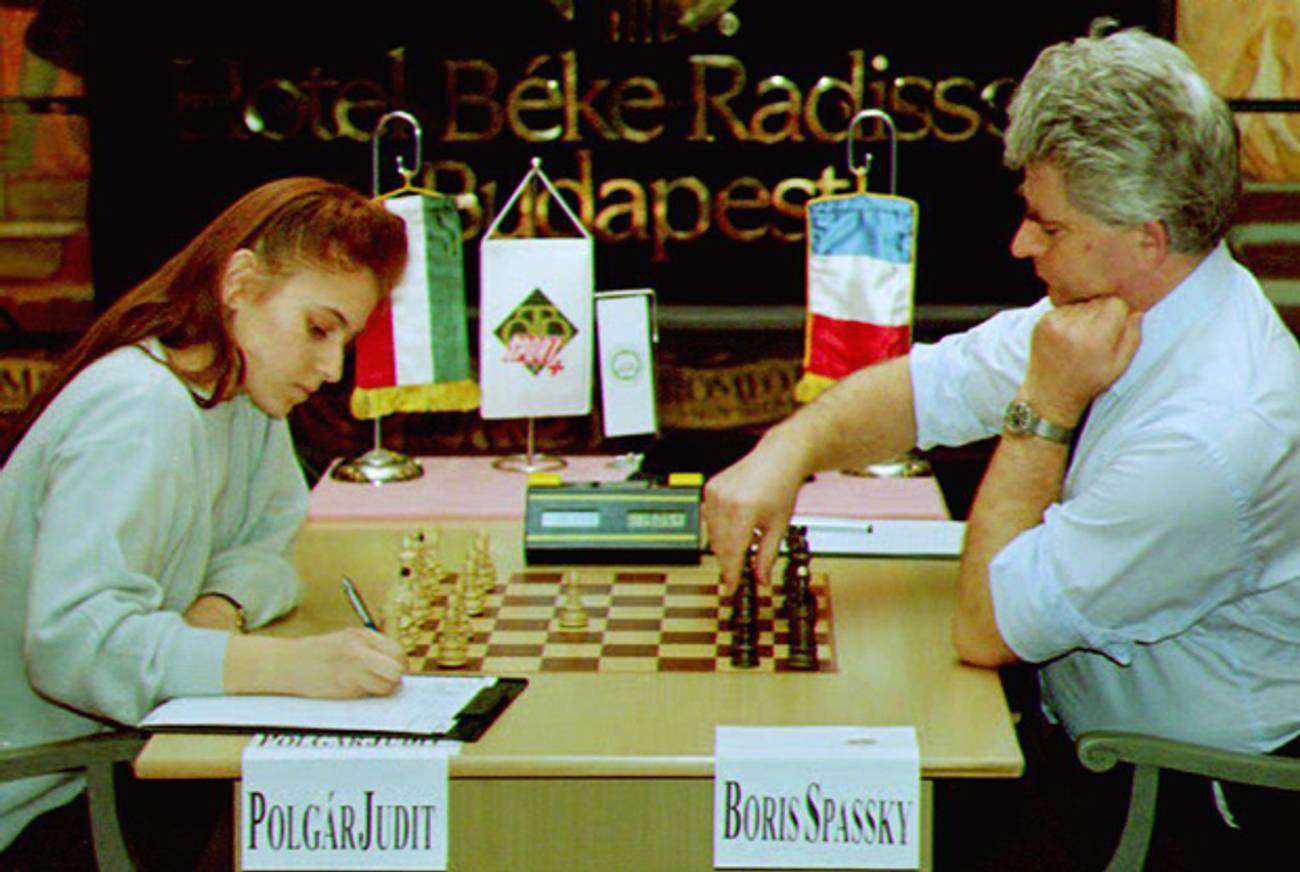

But it’s Judit, now 39 and the youngest of the Polgar sisters, who is widely considered to be the best female chess player ever. A grandmaster by the age of 15, she broke Fischer’s record as the youngest player to earn the esteemed title and has been the no. 1 ranked women’s chess player since age 12. Yet despite her ranking, Polgar has never competed in the Women’s World Championship. Polgar, who has defeated some of the strongest male players in the world—including current men’s champion Magnus Carlsen, former world champion Garry Kasparov, and Fischer nemeses Spassky and Karpov—objected to a tournament in which her competition was limited by gender.

“I have no problem with other women,” Polgar said in 2012, “but if I had played against ladies there would be a huge gap between the two of us.”

In August, Polgar announced her retirement from competitive chess, ending a several-decade run as the top-ranked female player. Members of the chess community were quick to praise the enormous significance of Polgar’s legacy.

“Judit Polgar obliterated the gender barrier in chess,” Hanon Russell, president of Russell Enterprises, a publisher of chess books, wrote via email. “She proved that women were able to play powerful, creative chess at the highest level. Judit has served as an inspiration not only for all chess players, but in particular to all the girls and women who have followed in her footsteps.”

“[Judit] has shown that there is no such thing as women’s chess or men’s chess: there is just chess,” wrote Kirsan Ilyumzhinov, president of FIDE.

Maurice Ashley, grandmaster and announcer for most major televised chess events, wrote, “I believe Judit’s biggest contribution to the game is that she destroyed the notion that women simply could not compete with the best chess players in the world. People really felt that a woman was simply incapable of challenging the players at the very top. She sent that idea to the graveyard.”

“By always competing in Open instead of Women’s events, Polgar effectively put to rest silly notions that women could not compete with men in chess, Chess Life editor Dan Lucas wrote. “Eventually, reporting of events in which she competed stopped referring to her as a woman player and simply referred to her as a player.”

“In the future, hopefully there will be more women in the game’s upper echelons and it will not be such a novelty, as it was with Polgar,” former New York Times chess columnist Dylan Loeb McClain wrote via email. “That would likely increase interest in the game. But even if that happens, it will not diminish Polgar’s accomplishment because she will always be the one who did it first.”

Chess.com’s Daniel Rensch pointed out that Polgar finished her career ranked as the no. 1 female player for 25 years straight. “As far as I know, not a single person or athlete can claim records of doing something for 25 years in any other sport.”

Related: Bobby Fischer vs. the Rebbe

Jonathan Zalman is a writer and teacher based in Brooklyn.