A Letter From Budapest

A personal quest becomes political, as Prime Minister Viktor Orbán transforms a once-flourishing democracy into the vanguard of new European authoritarian nationalism. A report for Hungary’s National Day.

I recently returned from a three-month stay in Budapest, where I was a fellow of the Institute for Advanced Study of the Central European University—a splendid graduate school of social sciences and philosophy founded by George Soros, which the government of Viktor Orbán has been trying to hound out of Hungary. My research is in literature and history, with occasional forays into film, but if you spend any time in Budapest or hang around the CEU these days, you cannot remain indifferent to the political climate. For one thing, the government’s steps against the university have been accompanied by a scurrilous ad-hominem campaign against Soros, whose anti-Semitic overtones are clear to all; for another, parliamentary elections are coming up in April.

Hungarian is my native language, but I left Budapest as a child with my parents when I was 10 years old, and for many years my knowledge of the language was rudimentary. That changed when, after the fall of Communism, in 1993, I spent six months in Budapest as a fellow of another Institute for Advanced Study, the now-defunct Collegium Budapest. It was then that I learned words like “concept” or “intellectual” in Hungarian, not my usual vocabulary when speaking with my mother or my aunt. In 1996, I published my book, Budapest Diary: In Search of the Motherbook, which was mainly the chronicle of a personal quest. I returned to Budapest for short visits after that, but my most recent visit dated from 10 years ago before the current Hungarian government was elected. I had been reading about Orbán’s evolution toward autocracy, and also followed from afar the government’s attempt to oust the CEU, part of a more general campaign in Eastern Europe and Russia to get rid of “foreign” entities with democratic ties. The university is a hub of intellectual activity in the center of Budapest, attracting students and visiting scholars from all over the world (including Hungary, of course) and providing employment to hundreds of Hungarians—as faculty, as administrators, librarians, computer support staff, receptionists, guards, maintenance crew, without forgetting the ladies who check your coat when you enter the building.

Last spring, the Hungarian Parliament enacted a law stating that any university incorporated abroad had to have a campus in its home country to operate in Hungary. The CEU, existing only in Budapest but incorporated in New York, is the only university that fits the description: The law was clearly targeting it and nothing else. Despite mass demonstrations in support of the university, the government stuck to its guns. After months of negotiation involving the CEU (whose rector, Michael Ignatieff, is an internationally respected scholar as well as a former politician, having led the Liberal Party in Canada for several years), the State of New York, and Bard College, a plan was drawn up that allied the CEU with Bard, thus satisfying the law’s stricture. The plan has been signed off on by all the officials on the American side and is awaiting the signature of Viktor Orbán and the approval of Parliament. But those won’t be forthcoming anytime soon—certainly not before the April elections, and maybe not afterward, either. If that’s the case, the university will have to move. Vienna is eager to receive it, and in fact, the rector has just announced (in a circular dated March 12) the planned opening of “satellite campus” in that city. But were the university as a whole to move, it would be a real loss for Hungary and one more sign of the erosion of democracy in the country. “They’re going after the CEU because they don’t want an independent, critically thinking population,” one friend (not connected to the CEU) told me. “Such people are harder to manipulate. They want to reduce everyone to dependence.”

During my months in Budapest, I spent many hours talking about politics with colleagues and friends, Jews and non-Jews, some of whom I’ve known for many years, while others I met for the first time; I also read a lot of Hungarian newspapers and magazines, and listened to radio (I’m not much of a TV watcher). While in 1993 my quest had been mainly personal, this time my obsession was political. The people I spoke with—academics at various universities, writers, journalists, as well as taxi drivers and the woman who cut my hair—were all critical of Orbán, but I forced myself to read the pro-government newspapers as well. I can’t pretend to be “neutral” in this report—I see nothing positive in the current evolution toward autocracy, but I have made an effort to be accurate, and to give an honest account of what I saw and read.

Viktor Orbán’s party, Fidesz, won the elections in 2010 by an overwhelming majority, ousting the Socialist Party which had been in power since 2002. Founded in 1991, Fidesz was originally part of a new wave of post-Communist, left-leaning parties, its name an acronym for “Young Democrats.” By 2010, however, the party and its leader were neither young nor left-leaning, nor very democratic. The party had had a brief stint in power from 1998 to 2002 and had been moving steadily rightward since then. In 2010, boosted by its two-thirds majority and the general turning of the political mood toward the right (2010 was also the year that saw the entry into Parliament of the extreme right-wing party Jobbik, notorious for its anti-Semitism and anti-Roma positions), Fidesz undertook a series of measures to consolidate its hold on the country: It changed the constitution to its own advantage, instituting new electoral rules in its favor, severely limited the number and broadcast range of independent TV and radio stations, and began systematically to take over provincial newspapers. Today, there is not a single independent newspaper in any Hungarian city outside Budapest, and even in the capital, their number is quickly dwindling. Independent TV and radio stations don’t reach beyond a 75-mile radius from the capital; to receive them, one has to subscribe to cable, and most people in the provinces don’t.

After winning again in 2014, Orbán advanced further toward authoritarianism, which he calls “illiberal democracy.” Since then, riding the wave of anti-immigrant sentiment that has also invaded Poland and gathered strength in Germany, Austria and Italy, among other Western European countries, Orbán has become more and more aggressive in attacking policies of the European Union concerning immigration, even while benefiting (both personally and politically) from huge subsidies provided to EU member states. Much of the money from the EU has gone into building and renovation projects in Budapest, which is good for tourism—central Budapest is looking gorgeous these days, and at night the Danube glows with illuminated bridges and monuments.

The building projects are lining the pockets of developers, most of whom are or have been personal friends of the prime minister. The previous Socialist government was also corrupt, people say—but one historian of contemporary Hungary told me when I met him last October that compared to the kleptocracy of today, the Socialists’ misdeeds were “child’s play.” According to the most cynical view, even the government’s campaign against the CEU has to do with real estate: The university occupies three large adjacent buildings, all beautifully renovated, on one of the most desirable streets in downtown Budapest, a stone’s throw from the Chain Bridge and other major tourist destinations; and it owns several other buildings nearby. “If the CEU is forced to move to Vienna, what do you think will happen to those buildings?” goes the cynical question.

In November I had lunch with a friend I first met more than 20 years ago, who is now a professor at the Hungarian university in Budapest, ELTE. He was very involved in politics back in the 1990s, harboring high hopes for post-Communist democracy in Hungary. Today, he told me, he has given up on politics—he just does his work and spends his free time with friends and family. “Just like under Communism”? I asked. “Not exactly, but yes—you could say I’m reliving my adolescence!” he replied with a laugh. In the waning years of the Kádár regime, in the late 1970s and 1980s, people in Hungary could lead fairly comfortable lives if they stayed out of politics. “Today, once again, the political situation is rotten, but living in Budapest is very pleasant!” my friend quipped. He is not Jewish, but Jews have told me more or less the same thing. “Yes, much of the official discourse is anti-Semitic,” one Jewish friend told me. “But there have been no physical attacks against Jews here, or against synagogues, which is more than one can say for France or Belgium.”

Life in Budapest can indeed be very pleasant if you are a relatively well-educated member of the middle class, Jewish or not. Globalization has brought giant malls with international stores that are crowded not only on weekends; one of these is the West End, a multistory extravaganza near the Western railroad station that’s bigger and more stuffed with luxury goods than many in the United States. Everyone seems to have a smartphone, and Hungary’s EU membership means they can call any other member country for no extra charge. The public transportation system is enviable, a network of subways, buses, tramways and commuter trains that seems to cover every inch of the city and its neighboring towns, and on which seniors ride for free. Budapest is a city of music, with world-class venues and artists; theaters are many and usually full. And of course, there are the pastry shop/cafes, where slices of Dobos Torta (a multi-layered cake with a hard caramel top) and Gerbeaud cake (multilayered, with dark chocolate and a hint of apricot jam) are lined up next to sour-cherry strudels and crescents filled with poppy seed or walnut paste. Several weeks before Christmas, the sidewalks and squares mushroom with illuminated open-air markets selling everything from mulled wine to leather gloves.

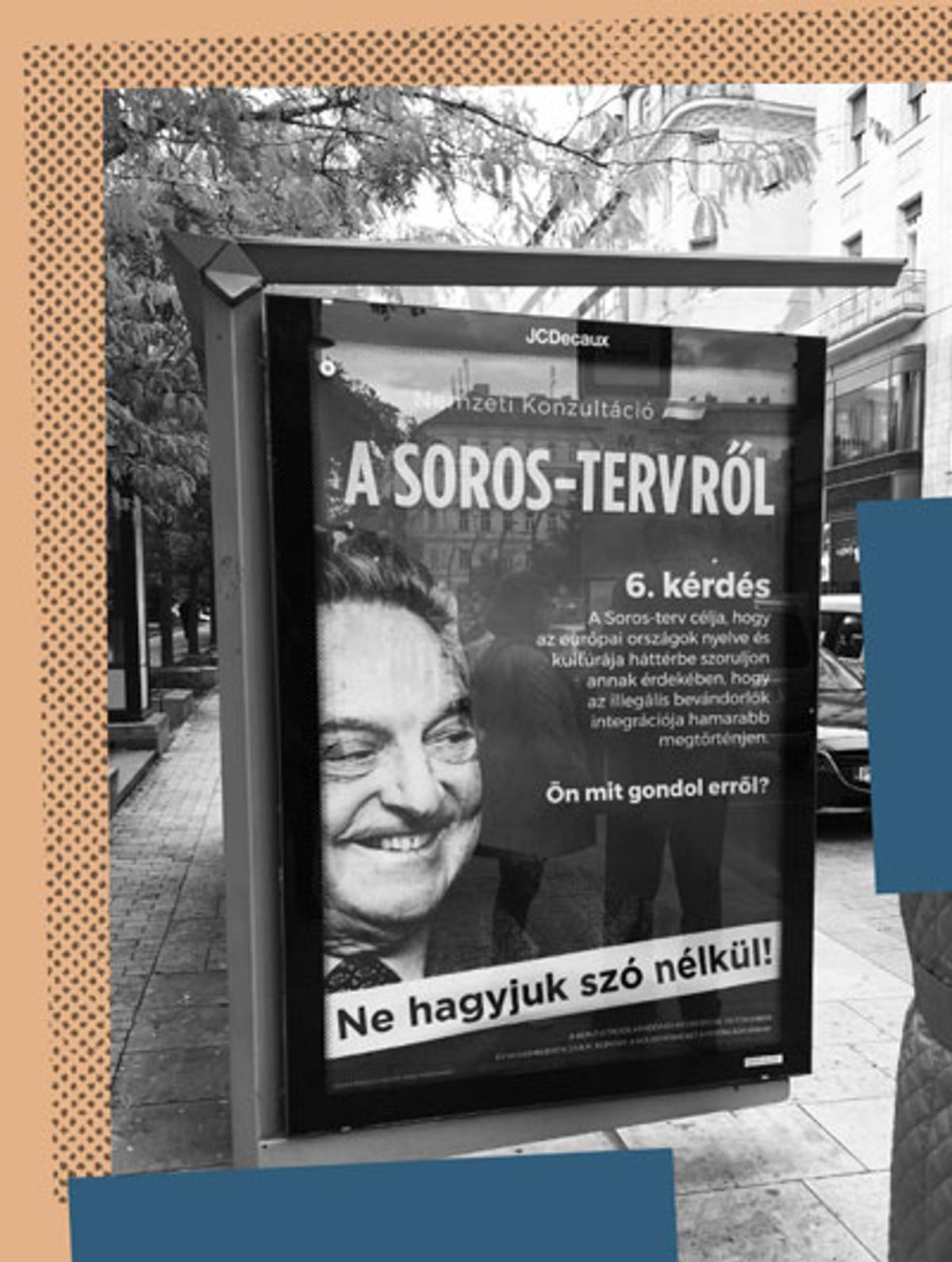

But how to describe the shock and revulsion I felt when I saw my first anti-Soros poster in the city? On a mild fall day in early October, a couple of blocks from the CEU in downtown Budapest, I glimpsed a photo of a laughing George Soros on the wall of a bus-stop shelter. It was part of a large poster, where paid advertising would normally go. Across the top of the poster, above Soros’s head, ran a line in large block letters: “A SOROS-TERVRŐL,” ABOUT THE SOROS-PLAN. And beneath that, “6th question. The aim of the Soros Plan is to squeeze the languages and cultures of European countries into the background, in order to facilitate the integration of illegal immigrants.” This is followed by a question in larger letters: “What do you think about this?” And on the bottom, running along the whole width of the poster, a banner headline: “Let’s not remain silent about it!”

I couldn’t believe my eyes. I had heard that already last summer, giant posters featuring the laughing face of George Soros had been plastered all over Hungary, carrying the admonition “Let’s Not Let Him Have the Last Laugh” (about what?), but I had been told they had been taken down after an international outcry. This was something new. Over the next few days, I saw several more posters at bus stops and street corners, each with a different “question”—or more exactly, with a different claim about the “Soros Plan”: No. 5 wanted to know what “you” thought about Soros’s idea that migrants should receive “lesser sentences” (lesser than what, it didn’t say) for crimes they committed; No. 3 claimed that the Soros Plan would allow “Brussels” (the EU) to forcibly relocate refugees who are currently in western Europe to eastern European countries, including Hungary; No. 4 spread the news that according to the Soros Plan, Brussels would force every country, including Hungary, to pay 9 million forints (about $35,000) to every immigrant; and so on, mind-numbingly, to No. 7, which announced that the Soros Plan proposed heavy fines and political measures against all countries that opposed immigration. “What do you think about this?” went the refrain.

I soon found out that these questions came from a flier the government called a “national consultation” (Nemzeti Konzultáció: Those words were also on the posters, way on top) and that had been mailed to Hungarian voters at the beginning of October. It was not a referendum, nor a binding vote of any kind, but an opinion survey, like a couple of others the government had floated since 2011. In fact, there is no such thing as a “Soros Plan.” While Soros published various opinion pieces and articles in 2015 and 2016, which the government claims together comprise a “plan” that in turn dominates the immigration policies of the EU, every proposal that the consultation attributed to the nonexistent Soros plan was false, and often explicitly contradicted by Soros’ own statements. Yet the fact that the plan does not exist did not prevent over 2 million Hungarians (out of a population of 10 million) from returning their surveys, according to a government announcement published in December. The announcement states this was “the most successful consultation of all time,” and the results prove that “Hungarians do not wish Hungary to receive any immigrants.”

It’s unlikely that many of the returned surveys were from Budapest: In Hungary, as in many other countries with a populist leader (not excepting the United States), there exists a clear division between the generally better-off and better-educated voters in big cities and those who live in depressed provincial areas. Hungary has over 3,000 localities, but only around 300 that qualify as cities or towns (as opposed to villages). The population of Budapest is around 2 million, while the other 8 million people are distributed among provinces where most localities have fewer than 15,000 inhabitants, and many have fewer than 5,000. The poverty rate in those localities is high, and the only source of information for most people is the government-controlled TV and radio. Orbán is popular there. He has obviously figured out a way to make the most of the nationalist, xenophobic wave—and to tap into an age-old anti-Semitism as well, by urging Hungarians to oppose the “plan” by a “billionaire speculator” (the tag that unfailingly accompanies Soros’s name in all the newspapers sympathetic to the government—no need to mention that he is Jewish, it goes without saying).

Not a day went by, from October to December, when I did not see Soros’s name, in huge letters, on the front page of one government-allied newspaper or another, two of which I bought compulsively: “Europe is caught in Soros’ net,” screamed the headline in Magyar Idők (Hungarian Times) on Oct. 7. “The Soros Fortune Is Starting to Work All Over Europe,” reported Magyar Hirlap (Hungarian Journal), quoting a government spokesman, on October 20; a few pages later, the paper printed a full-page color reproduction of an anti-Soros poster, the one about how Soros wanted every immigrant to receive 9 million forints from the government. According to these newspapers, Soros stands to make a lot of money with his nefarious “plan”—how exactly is not clear, but logic is not paramount here. What is clear is that the all-powerful Jewish speculator wants to ruin European culture by allowing undesirable aliens to invade Christian Europe.

How an 87-year-old Hungarian-American philanthropist (Soros left Hungary as a teenager, in 1947; over the past three decades he has funded hospitals, schools, and many other socially useful institutions all over eastern Europe) has become Public Enemy No. 1 in the minds of many Hungarians is a truly intriguing question. But although this kind of public campaign against a single individual is unique to Hungary, we know that Soros is a target of the alt-right in the U.S. as well—and he is a target even in Israel, at least among the supporters of Benjamin Netanyahu. In early December, the only remaining opposition daily, Népszava (People’s Word), headlined that “Orbán is running against Soros” in the upcoming elections.

The Jewish response to this campaign, and to the Orbán government in general, has been—well, mixed. Some Jewish liberals, like other opponents of the government, maintain that Orbán’s autocratic moves are so dangerous, he must be ousted at all costs in April. This argument can lead to unprecedented conclusions: in late November, all the newspapers reported the surprising news that the highly respected 88-year old philosopher Agnes Heller, a survivor of the Holocaust in Hungary, had attended a meeting at the Jewish cultural center Spinoza, where Gábor Vona, the leader of the extreme-right wing party Jobbik, announced that his party was reaching out to Jews—a “move to the center” that Jobbik had initiated some time before. And not only had Heller attended the meeting—she gave interviews in which she explained why all the opposition parties should unite against Fidesz in April, even if it meant an alliance between the left parties and Jobbik. When Jobbik first entered Parliament in 2010, it was outspokenly anti-Jewish and anti-Roma, leading skinhead-type marches; while not a formal ally of Fidesz, it was a kind of ally on the far right. Recently, however, Jobbik has not only toned down its racist rhetoric (at least in public), it has also become a vocal critic of government corruption—hence, an enemy of Fidesz.

According to Heller, who is known the world over for her philosophical writings, today it is Fidesz that has become the extreme right-wing party, not Jobbik. “Everyone says that we have to protect the country from the anti-Semites. But for God’s sake, I’m the Holocaust survivor! And with that experience behind me, I say that if there’s no collaboration with Jobbik, then Fidesz will remain in power. If Fidesz remains in power, it will be a tragedy for Hungary,” she stated in a long interview in the liberal weekly Magyar Narancs on Nov. 30. She is convinced that if Orbán retains power, he will destroy the last remnants of democracy in Hungary, starting with the free press. “We should pay attention not to what Jobbik said five years ago,” she says, but to what it says now. “Just hold your nose and do what’s necessary to oust Fidesz.”

Heller’s argument apparently hasn’t convinced many people. A number of rebuttals followed her Magyar Narancs interview, notably a long and highly documented one published in the weekly Élet és Irodalom (Life and Literature) on Dec. 8 by two political scientists, who argued that Jobbik’s newly moderate rhetoric couldn’t be trusted, since all it takes is a few clicks to move from Jobbik’s web site to others expressing the most hateful ideas. Furthermore, as others have pointed out, any tactical alliance between the small left-wing parties and Jobbik would fall apart the minute it came to governing. And besides, it would necessarily lead to Jobbik gaining power in at least some local governments. “What would happen if Jobbik became the party in power in some small town? How can we know what they would do? It’s a bad idea,” said Gábor T. Szánto, a writer (he wrote the short story on which the highly acclaimed film 1945 is based, and also collaborated on the scenario) whom I have known for a long time and whom I saw in December. Szánto, who is also editor-in-chief of the Jewish monthly Szombat (and a Tablet contributor), pointed out that the Left parties have been unable to get together to create a unified front: “They’re all too involved with themselves, they don’t think strategically,” he told me. Right now, in addition to the Socialists, who have lost strength dramatically over the past years, there are a couple of newer left-wing parties, including the LMP (“Lehet Más Politika,” Politics Can Be Different) and the recently formed Momentum party, which has no representatives in Parliament yet. But even if they all got together, it’s unlikely that they could beat Fidesz.

Meanwhile, some Jewish institutions are on quite good terms with the current government. Prime Minister Netanyahu paid a State visit to Hungary last summer. And Chabad, which runs several synagogues as well as a yeshiva in Budapest, is doing very well. On the first night of Hanukkah, I attended, along with hundreds of others, a celebration and candle-lighting ceremony on the boulevard in front of the Western train station. There was singing and dancing to klezmer music, and Orthodox rabbis gave speeches before the candles were lit by two people who were hoisted up to the giant menorah. When one speaker reminded the crowd that President Trump had just announced the United States would recognize Jerusalem as the capital of Israel, many people cheered. (Many did not). This Jewish crowd had no visible worries about anti-Semitism in Hungary, or at least in Budapest.

And there are many other manifestations of Jewish life in the city that point in the same direction: the Jewish Film Festival at the beginning of December attracted sold-out crowds over several days; the Jewish cultural centers Spinoza and Bálint Ház are thriving; many synagogues flourish, and Jewish schools are attracting students from all over the city; the Jewish bookstore, Láng Téka, near Margit Bridge, is often full (it’s true that it’s very small), and the Jewish publishing house Múlt és Jövő, which was started more than 20 years ago by János Kőbányai, continues to put out excellent books as well as a quarterly magazine by the same name. Hungary has a Jewish population of more than 100,000 (though far fewer declare any Jewish affiliation), which is larger than any other Eastern European country, and most of them live in Budapest. As my Jewish friend reminded me, there have been no physical attacks against Jews or vandalism against synagogues. A number of other Jewish friends have said that Orbán is personally not anti-Semitic, despite his shameless exploitation of anti-Semitic tropes in the anti-Soros campaign. (If this recalls our current American president, it should).

So, yes: Life in Budapest is quite pleasant, even if the politics is rotten. How long this will continue, however, is an open question. On my last day there, just before Christmas, I had coffee with a couple I had met two months earlier—they are both professors of literature teaching at Hungarian universities, he in Budapest, she in another city. Our conversation soon turned to the political climate. Last spring, they told me, when the government first sought to outlaw the Central European University, mass demonstrations were held in support of the university all over the city, and some professors in Hungarian institutions, both in Budapest and elsewhere, signed a petition of protest on Facebook. Very soon after that, the rector at one university in Budapest called together all those who had signed, wanting to know who had initiated the petition, on whose computer it was composed. The rector at a university in another city told one young woman professor who had signed, “You have two young children, think about them.” Such veiled threats of reprisal for speaking out are not new, my friends told me. It’s well-known nowadays that anyone who is considered a critic of the regime will not receive research or fellowship support from government-backed institutions if they apply for it. So people are becoming cautious. “’Don’t talk about this to your friends,’ that’s what I sometimes tell my son,” he said. Are people actually afraid? I asked. “Not afraid, exactly, but cautious. It’s a bit too reminiscent of the Kádár regime,” he answered.

Viktor Orbán’s party is expected to win the elections again on April 8, maintaining him in power for another four years. What will happen then is not at all clear. But it’s sobering to contemplate that Stephen K. Bannon considers him a “hero,” according to an article published this week in The New York Times. On a recent European lecture tour where he spoke to populist audiences in France, Italy, and Switzerland and met with leaders of the far-right Alternative for Germany party, Bannon declared that Orbán is “the most significant guy on the scene right now.” Could Agnes Heller have been right after all?

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Susan Rubin Suleiman is professor emerita at Harvard University and the author, most recently, of The Némirovsky Question: The Life, Death, and Legacy of a Jewish Writer in Twentieth-Century France.