It happens sometimes in journalism: that no matter how hard you try, how much you research, and how penetrating you think your questions are to your interview subject, you still miss the scoop. And this week, it happened to me.

I had, as many of you already know, the thrill of my journalistic life a few weeks ago interviewing Sheldon Harnick, the legendary lyricist of Fiddler on the Roof, Fiorello!, and She Loves Me in advance of his new Fiddler-related show at the Manhattan 92Y. But I somehow failed to excavate the important factoid that Rothschild & Sons, a new, one-act adaptation of The Rothschilds, Harnick’s 1970 musical about the famed Jewish banking family, will premiere Off-Broadway at the York Theater in October.

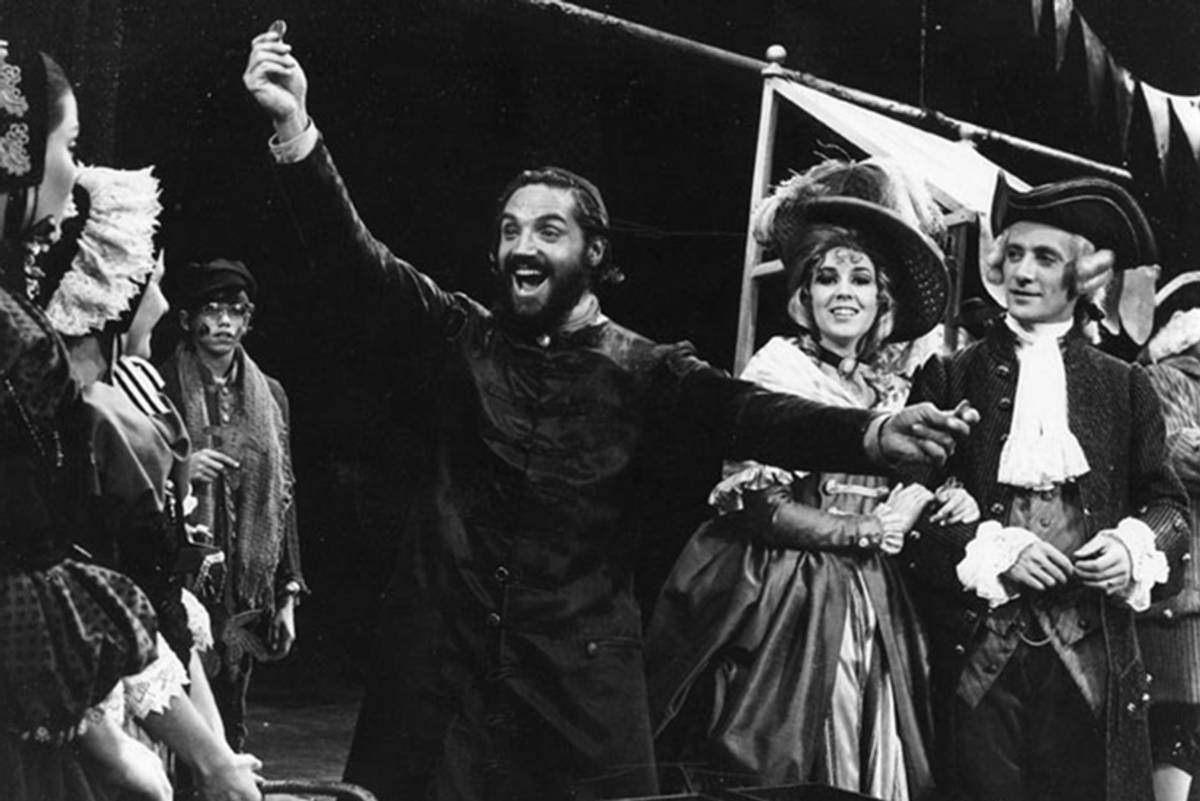

As the final collaboration between Harnick and his longtime partner, the composer Jerry Bock, and if not quite a flop, not quite a hit either, The Rothschilds in its original incarnation occupies an interesting place in Broadway history: everyone has heard of it, but nobody knows it. It’s not the kind of show you’ll hear someone singing a song from at even the most erudite piano bar, if you know what I mean. (And you do. We’ve probably been to that bar, together.) But I’ve always been most intrigued by the subject matter. Fiddler on the Roof, by far Harnick and Bock’s most successful show (or, arguably, anyone’s most successful show) was lightning in a bottle, a perfect distillation of the talents of the creative team and the richness of its subject matter in source material. The Rothschilds, staged as the Harnick/Bock collaboration was perhaps running out of steam—or at least, straining under the abundance of its success—has always seemed like an attempt to catch the lightning twice, with similar subject matter and dramatic conflict.

To wit: The Rothschilds opens in the Jewish ghetto of Frankfurt, where the illustrious banking family made its humble start. (Let us not forget, the Tevye of Sholem Aleichem’s original stories was always dreaming about all the things he could accomplish if he “were a Rothschild”—not the more translatable and more generally American “rich man.”) Much of the early plot revolves around Mayer Rothschild—the eventual paterfamilias of the dynasty, who took the first uncertain steps out of the ghetto and into the outside world—and his efforts to wed his beloved fiancé Gutele in a repressive system that allows only 12 legal Jewish marriages a year (all the better to keep the Jewish population low).

But there has always seemed to me something poignant in Harnick and Bock’s choice of material here; that the men who made their fortune writing about poor Jews finished off their partnership writing about rich ones. Fiddler is about the struggle; The Rothschilds, despite its Act One obeisance to the hardships of being Jewish in 18th century Germany, is about success. Perhaps that’s part of the reason for its relative lack thereof in the musical theater canon. The original audiences of Fiddler were able to look at the uncertain world of their grandparents and great-grandparents on the stage, knowing that one day, in America, things would turn out all right. The Rothschilds, which can be seen as both a prequel and a sequel to Fiddler, depending on how you look at it, portrayed dazzling success in a luxurious Jewish-European world that they knew would disappear—and that while it existed, looked down its nose at poor Ostjuden strivers like Tevye. It’s a truism that poor people dream of one day being rich, but comfortable people, especially of the American Jewish persuasion? It’s pretty clear from our culture—not to mention our voting records—that we don’t have to dig too deep to remember where we came from.

Which is certainly part of the insight behind The Rothschilds’ new adaptation, Rothschild & Sons, which reportedly concentrates more on the “love story” between the father and the sons who would conquer the world rather than the vagaries of high finance that made it possible. After all, when you get down to it, Mayer Rothschild was just a worried Old World Jewish proto-banker with a whole lot of rapidly modernizing children to feed. Let’s just hope he likes who they marry, no?

Previous: An Interview With the Man Who Made Tevye Sing

Rothschild and Hilton Dynasties to Merge

Related: Family Fortune

Rachel Shukert is the author of the memoirs Have You No Shame? and Everything Is Going To Be Great,and the novel Starstruck. She is the creator of the Netflix show The Baby-Sitters Club, and a writer on such series as GLOW and Supergirl. Her Twitter feed is @rachelshukert.