A Yiddish-English Dictionary for the Ages

A new dictionary co-edited by Gitl Schaechter-Viswanath was created by the might of familial love and the need to keep Yiddish up-to-date

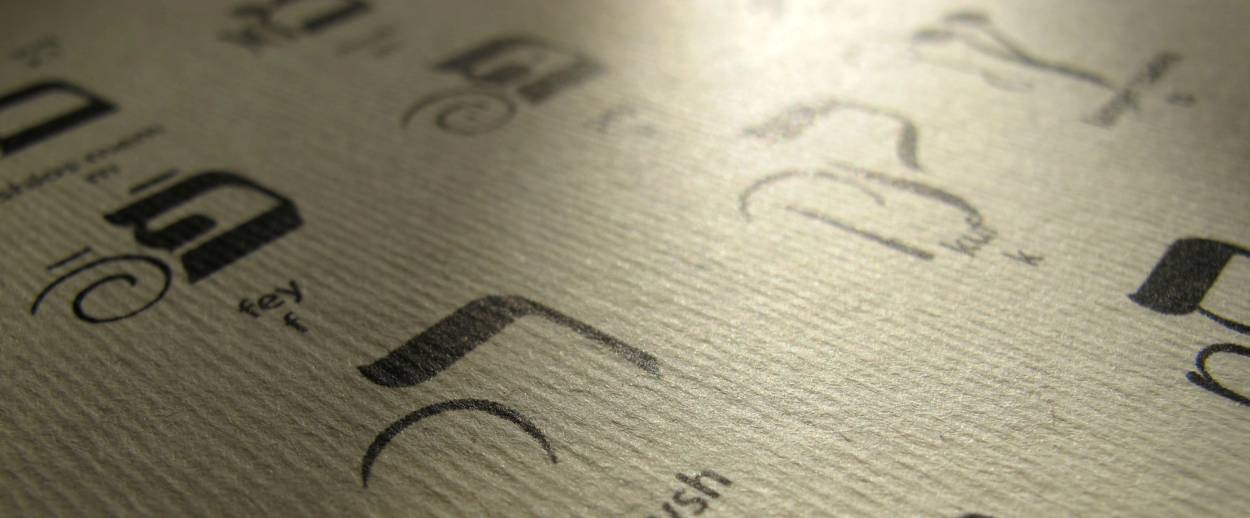

This summer, Yiddish-language poet Gitl Schaechter-Viswanath was watching a play at Yiddish Vokh, a week-long vacation spot near the Taconic Mountains for families where the only language spoken is Yiddish, the language of a majority of world Jewry before the Holocaust that is now spoken by around 150,000 people in the U.S. Her father, Mordkhe Schaechter, a leading Yiddish linguist who died in 2007 at the age of 79, created the event 41 years ago as an immersive language program for students. It’s since evolved into the world’s only opportunity for people from all walks of life to spend a week together interacting in Yiddish only. (Non-Yiddish speaking family members are not welcome as the goal is complete immersion.) People come from as far as Australia for the chance to be in this environment where they can experience lectures, classes, workshops, swimming, sports, campfires, talent and game shows, and klezmer dancing, entirely in Yiddish.

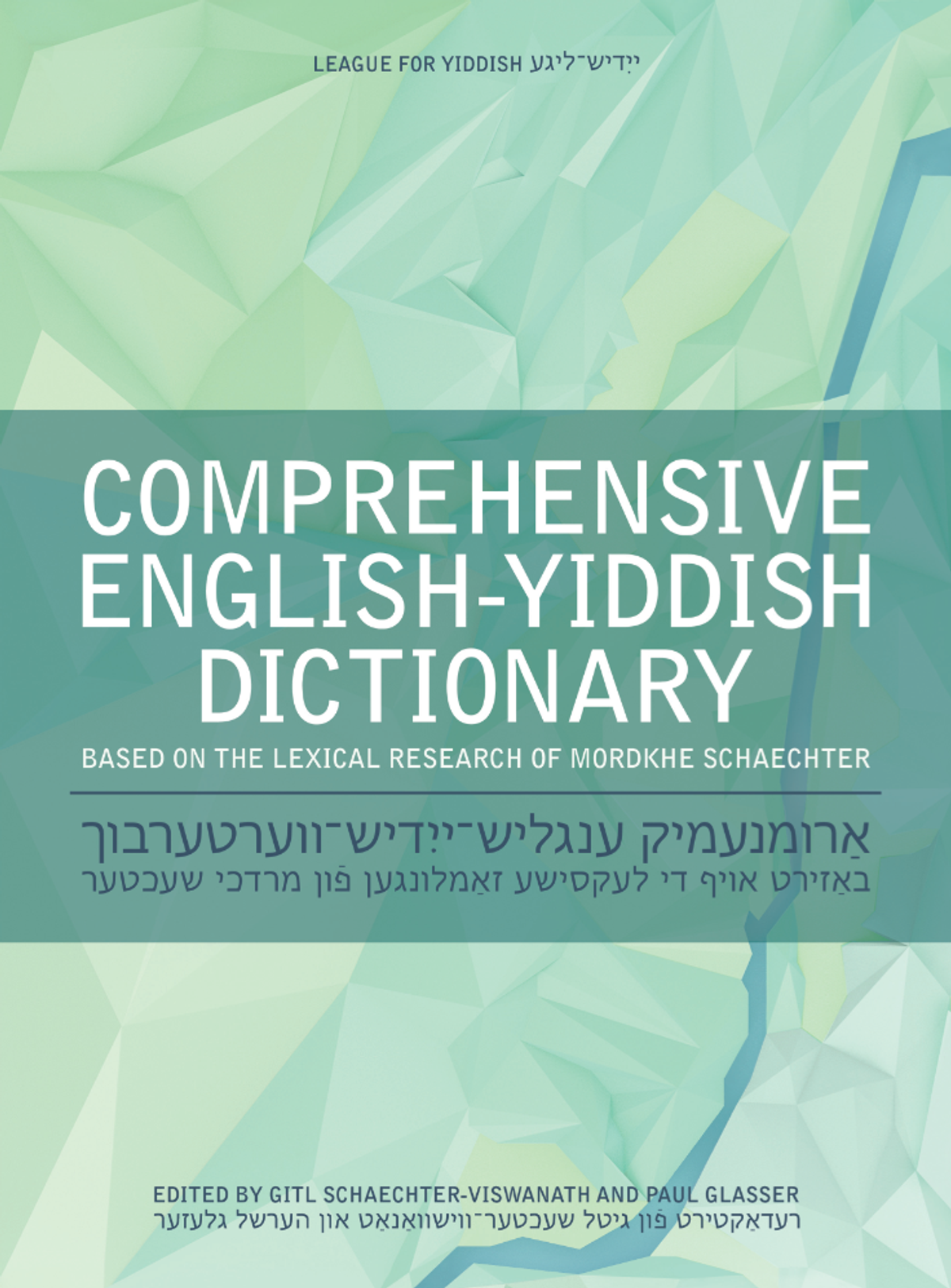

During one performance, a mother wanted to tell her child the Yiddish word for rock candy but she didn’t know how to say it. So, right then and there, onstage, she consulted the dictionary—Schaechter-Viswanath and Paul Glasser’s new Yiddish/English dictionary, a historic, comprehensive reference work with nearly 50,000 entries and 33,000 subentries that was released shortly before Yiddish Vokh—and found the correct word: kandl-tzuker. The audience laughed its approval along with the work’s pleased authors.

The Bronx-born Schaechter-Viswanath has been formally working on the dictionary for 16 years, but she essentially began preparing for it when she was just a child. At 12, her father, a linguist who taught at the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research, Columbia University, and the Jewish Theological Seminary, who was the editor of the YIVO’s Yiddishe Shprakhe journal and author of a number of books on the language, would pay her to act as her assistant, or his “right hand,” as he would say. She would sit at their dining room table and write English words on index cards for him that needed Yiddish equivalents. When her father was 70 he proposed creating a dictionary to modernize and update the existing Weinreich dictionary and include modern terms that were not found in it. She said she “wasn’t keen” on the idea since she had three young children and worked full time in nursing. However, the previous Yiddish dictionary had not been in print for 32 years and she acknowledged that a new one was “long overdue.”

When her father had a stroke in 2002, Schaechter-Viswanath vowed to continue their project. She said the dictionary became her “fourth child” and that she worked on it “obsessively.” She said she is “happy [to] have Shabbos in my life or I would have worked seven days a week.” She added, ruefully, “ It’s been a difficult year. I have to relearn how to relax, sit on the sofa, and read a novel.”

Though the preeminent Yiddish-English dictionary for those who speak the language was published by Uriel Weinreich in 1967, it contained only 20,000 words. By contrast Schaechter-Viswanath’s dictionary, published by Indiana University Press, has 83,000 entries in its 850 pages. Her dictionary is meant for those living modern lives in Yiddish and actively speaking the language for all their day to day activities.

As a starting point, Schaechter-Viswanath went through a modern Hebrew-English dictionary. She also looked at a Yiddish dictionary published in the 1920’s by Alexander Harkavy and a Russian-Yiddish one from 1984. She learned from what kinds of entries other comprehensive dictionaries had compiled, but still needed to be sure hers was up to date for physicians or social workers needing to communicate with Yiddish speaking clients. Schaechter-Viswanath’s dictionary is meant to help those who are speaking and using the language in 2016 as opposed to those translating written texts.

Schaechter-Viswanath’s three siblings are solidly involved in the Yiddish world too. Her oldest sister Rukhl is the first American-born editor of the Forverts, in its 119-year existence. Forverts publishes articles in the standardized Yiddish spellings her father cherished and believed in, a change from previous generations. (Rukhl has picked her top ten Yiddish words from her sister’s work such as flip flops (fingershikh) highlighter (der tekst-markirer) and post-traumatic stress disorder (di travme-krenk). Blitspost is Yiddish for email, in case you were wondering. Her sister, Eydl, is an artist and lives with her family of seven children in Tsfat where she teaches Yiddish to those women who are joining the community. Her brother, Binyumen, is an accomplished musician and composer who conducts the Jewish People’s Philharmonic Chorus.

Schaechter-Viswanath studied Russian at Barnard and Yiddish at the Jewish Teacher’s Seminary/Herzliyah, which existed to train teachers for secular Yiddish schools. Then, she went to nursing school. She met her husband who is from India and a native Tamil speaker when he was walking the streets of New York in 1985. He had seen the Workman’s Circle Building on East 33rd street and, curious about the language on the sign, walked in, and signed up on the spot for a Yiddish class. Soon, he was good enough to attend Yiddish Vokh. And when Gitl saw the Indian name on the registration form she thought, “I’ve got to meet this guy.”

The family love of the language has persisted as every one of Mordkhe Schaechter’s 16 grandchildren is a Yiddish speaker. Just as Schaechter-Viswanath helped her father as a child, her son-in-law helped her with his crucial computer acumen. Schaechter-Viswanath had started the project on a Macintosh in 2000, but at a certain point, all her data was orphaned without a way to access it. But her son-in-law James Conway was able recover the files. She said happily, “God sent me a son-in-law and he knew computers.”

More than that, though, her Boston-born son-in-law, who grew up in Belgium, had been planning to speak French to future grandchildren. But when her grandson Psakhye Eliezer was born, she heard Conway speaking Yiddish to the baby. She asked him why the shift in the plan, and he explained that to communicate with his son he “wanted a language that comes from the heart.” Schaechter-Viswanath added, “That is a reason in itself to write a dictionary for the coming generations.”

The manuscript was submitted on February 1, 2016 which happened to be the week of Mordkhe Schaechter’s ninth yarzheit. A bilingual program to celebrate the publication of the dictionary will occur at YIVO on Sunday, November 13.

Beth Kissileff is the editor of the anthology Reading Genesis (Continuum, 2016) and the author of the novelQuestioning Return (Mandel Vilar Press, 2016). Visit her online at www.bethkissileff.com.