Advocate

Norman Eisen, an old friend of Obama’s from Harvard Law School, is bolstering the forces of liberalism as ambassador to the Czech Republic

One day last August, a mid-level bureaucrat in the Education Ministry of the Czech Republic hand-delivered a complaint to the American Embassy in Prague. Ladislav Bátora styled himself a latter-day Martin Luther, but the target of his anger wasn’t the Catholic hierarchy but a Jewish American named Norman Eisen. Eisen, the U.S. ambassador, had signed an open letter supporting the first-ever gay pride parade to be held in the Czech capital—and Bátora was angry.

Bátora’s letter, signed by members of a far-right organization that goes by the acronym D.O.S.T., (meaning “enough” in Czech, and whose symbol is a clenched fist hitting a table), claimed that the festival was “organized by groups of homosexuals and lesbians whose demands against the Czech public significantly exceed the framework of mere tolerance.” Citing Ronald Reagan, whose anti-Communism has made him an enduringly popular figure in the Czech Republic, Bátora wrote that Eisen had betrayed the former president’s legacy and threatened to rupture the “good relations between our nations.”

American ambassadors, particularly those in small European countries, aren’t supposed to be in the business of stoking controversy. Not so for President Barack Obama’s appointees. Early last year, a State Department investigation revealed that the former ambassador to Luxembourg, a major Democratic Party fundraiser named Cynthia Stroum, had so demoralized her staff that some career foreign-service officers working under her fled for posts in Afghanistan and Iraq. Last month in Belgium, Ambassador Howard Gutman provoked a firestorm in the United States when he intimated that Muslim anti-Semitism in Europe was largely a response to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. On the surface, Eisen and Gutman have much in common: Both are prominent Democratic Party fundraisers, lawyers, and the children of Jewish Holocaust survivors. But their respective controversies could not have been more different: Whereas Gutman’s remarks provided fodder for those who seek to blame Jews for the hatred directed at them, Eisen’s intervention bolstered liberalism in a country that, still seeking its place in the post-Communist era, badly needs it.

The Czech Republic is known for its carefree attitude toward sex and sexuality: It has the highest divorce rate on the continent; it’s a popular destination for British stag parties; nearly half the population identifies as atheist; and it’s a major hub for the production of gay pornography. But these ostensible signifiers of social tolerance belie what is in fact a deeply conservative society.

Czech President Vaclav Klaus, for one, took umbrage at the fact that Eisen, along with 12 other Western ambassadors, voiced support for Prague Pride. The same day that Bátora marched on the U.S. Embassy, Klaus, a founder of the country’s biggest right-of-center political party, issued his own statement, declaring: “I can’t imagine any Czech ambassador daring to interfere by a petition with the internal political discussion in any democratic country in the world.” (Klaus had made his own views on the parade well known the previous week by defending an aide who had referred to gays as “deviant fellow citizens.”)

Eisen, 51, whose mother is a Czechoslovak Holocaust survivor, was now thrust into the center of a political controversy that had been roiling the country for months. Bátora had already been fingered as a man with unpalatable views: A group of Czech senators called for his dismissal from the Education Ministry a week before he delivered his missive to Eisen. The senators had raised concerns about Bátora’s involvement with a now-defunct far-right political party that promoted the expulsion of Czech Roma citizens. Bátora had also praised as “brilliant” a 1925 anti-Semitic book called The Adulteration of the Slavs, which approvingly cites The Protocols of the Elders of Zion, Henry Ford’s The International Jew, and the works of German writers who would later go on to become leading figures in the Nazi Party.

Bátora’s presence in the Education Ministry threatened the country’s fragile center-right coalition government. (The most admired Czech in the world, Vaclav Havel, denounced Bátora from his sickbed.) Foreign Minister Karel Schwarzenberg, a distinguished Czech political figure and founder of the center-right TOP ’09 party, reportedly called him an “old fascist.” But it was Ambassador Eisen’s provocation that ultimately led to Bátora’s downfall.

On Aug. 11, just a few days after receiving Bátora’s letter and in the midst of the weeklong pride festival, Eisen delivered a speech at a workshop on hate-crimes prevention in Prague. Praising New York’s recent legalization of gay marriage and the fifth anniversary of the Czech government granting same-sex civil partnerships, Eisen took a not-so-subtle shot at Bátora. Lauding the Czech Republic for being “in many ways more progressive on the issue of LGBT rights than my own,” he noted that, unfortunately, “there are still those in this country that express intolerant views.”

A few days after the parade, emboldened by picking a fight with the American ambassador, Bátora wrote on his Facebook page that Schwarzenberg, the foreign minister, was a “sorry little old man.” The website Czech Position reported that, “The war of words might have simmered on a slower boil had Bátora … not made headlines last week for condemning US Ambassador Norman Eisen and other ambassadors’ support for Prague Pride.” In October, after ministers from Schwarzenberg’s party threatened to bolt the government, Bátora resigned. Robert Basch, of the Open Society Fund-Prague, told me that the fact that Eisen threw his weight as American ambassador into the dispute over Bátora was crucial in helping the Czechs sort out the problem of creeping extremism. “The open letter was really for us very important for supporting Prague Pride as such,” he says. “Especially now when a conservative elite is in power, especially President Klaus, there really was a strong influence to stop this kind of event in the Czech Republic.”

***

When Eisen arrived in Prague last January, American-Czech relations were at their lowest point since the end of the Cold War. The embassy had been vacant for 18 months since the resignation of the previous ambassador, a George W. Bush political appointee who left at the start of the Obama Administration. In July of 2009, a group of distinguished Central and Eastern European leaders, including former Czech President Havel and former Polish President Lech Walesa, signed an open letter to Obama expressing fear that “Central and Eastern European countries are no longer at the heart of American foreign policy” and that “Russia’s creeping intimidation and influence-peddling in the region could over time lead to a de facto neutralization of the region.” The administration’s much-publicized reset with Russia alarmed Czech leaders, who feared that their interests and those of the other nations in the post-Soviet space would be demoted in pursuit of an entente cordial with Moscow.

Two months later, in September 2009, as if to confirm these fears, the Obama Administration abruptly announced that it would cancel the placement of anti-ballistic missile sites in Poland and the Czech Republic. Though the Czech government did not publicly decry the move, (unlike the Poles, whose country had been invaded by the Soviet Union 70 years earlier to the day), the view of Czech officialdom was encapsulated in the remarks of former Defense Minister and Ambassador to the U.S. Alexandr Vondra, who called it “a U-turn in U.S. policy.”

The ambassadorship to the Czech Republic, (a small country that, due to its size and the fact that it’s not in the Eurozone, does not play a leadership role in Europe), is a plum assignment generally filled by political appointees—not career diplomats. Since the rebirth of independent Czechoslovakia in 1989, the country has been one of the United States’ most steadfast allies, so the ambassadorship is a relatively easy posting. But as the Obama Administration has emphasized repairing relations with Russia, the job has come to carry new burdens. Consider the way in which much of the Czech political establishment viewed the Obama Administration at the time of Eisen’s appointment. In a May 2010 speech at the Atlantic Council, a Washington-based think tank, just months before he would re-enter government as defense minister, Vondra slammed Obama’s foreign policy as “enemy-centric,” alleging that it gives “carrots” to adversaries like Russia and China while failing to stand by allies.

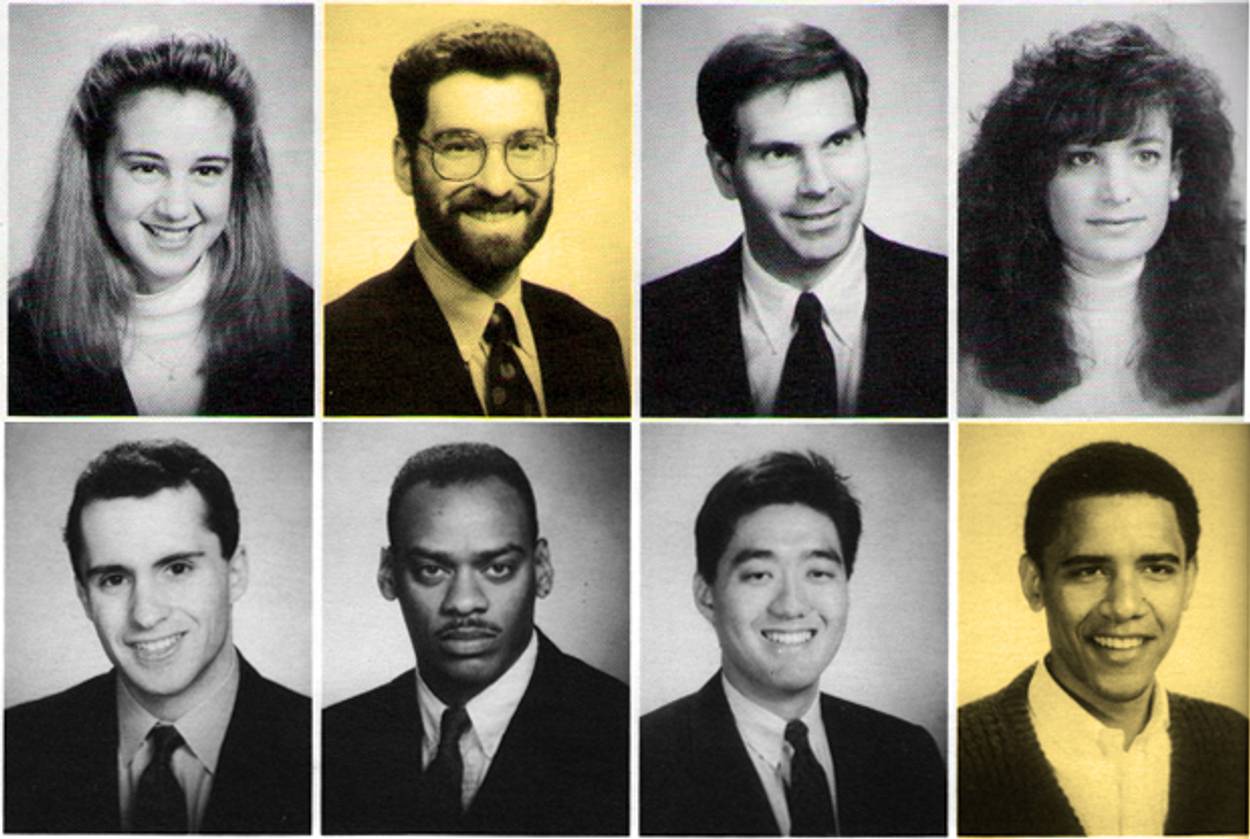

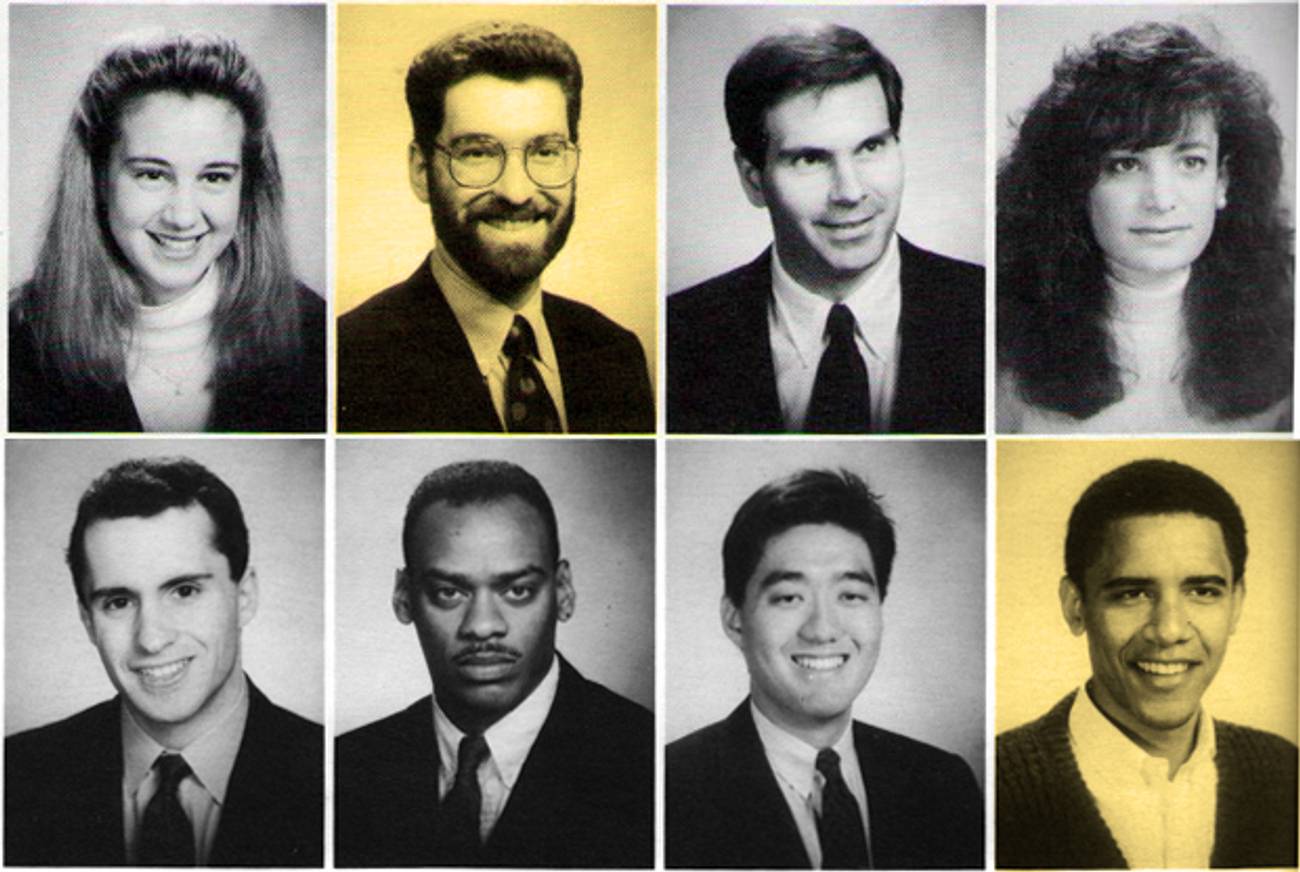

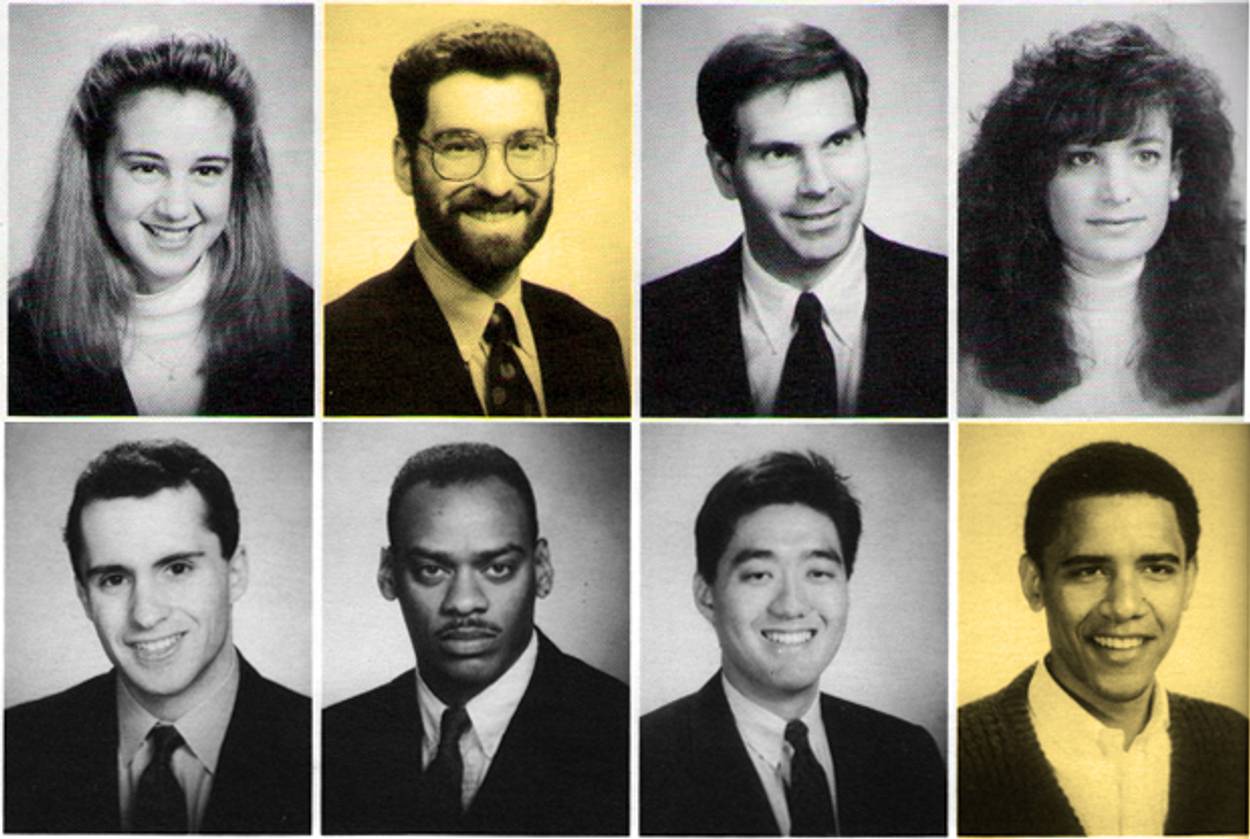

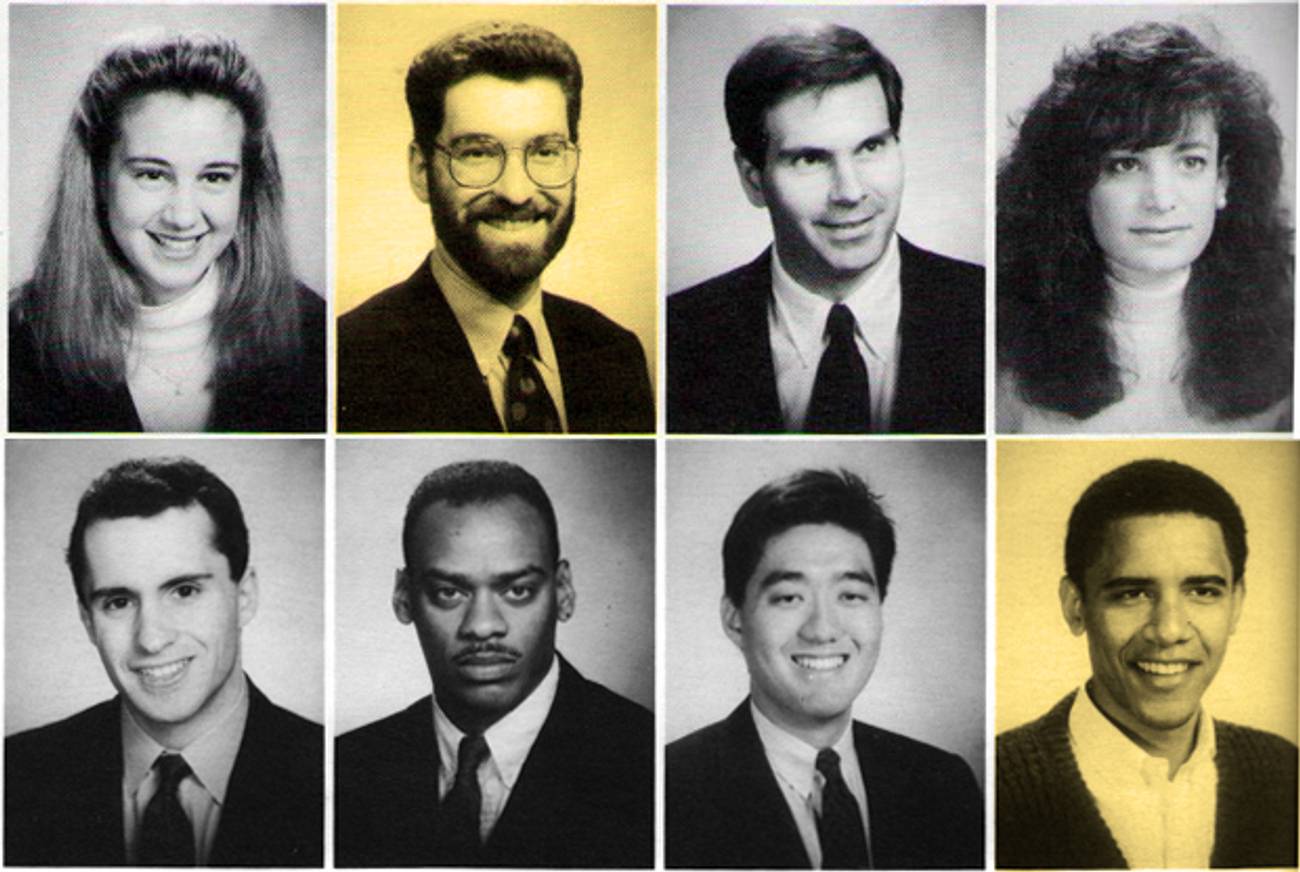

Eisen, who befriended Obama at Harvard Law School, says that the job was never on his radar. “I thought of that as something that people did when they were further along in their careers and their lives generally,” he says. After two years serving as the president’s Special Counsel for Ethics and Government Reform, or ethics czar—his nickname was “Mr. No”—Eisen’s plan was to return to Zuckerman Spaeder, the Washington law firm where he had practiced for nearly two decades. (Over the past decade, Eisen has donated some $60,000 to the Democratic Party and its candidates, and in the 2008 election cycle, he raised over $200,000 for Obama’s presidential campaign as a bundler.) Eisen was concerned not just with the strain that being ambassador might place on his family—he is married to Georgetown University Professor Lindsay Kaplan and has a young daughter—but on his own ability to deal with the horrors his parents experienced in Europe.

The president had other ideas. Obama knew Eisen’s family history—and his connections to the Czech Republic—intimately. The two had become fast friends at Harvard, where they were older than the majority of their classmates. “We had both done public interest work after college and before law school, I for the Anti-Defamation League in Los Angeles, he as a community organizer in Chicago, and we were both 28 when we arrived in Cambridge,” Eisen recalls. They remained close after graduation.

“The president thought it would be a remarkable thing for the son of a Czechoslovak Holocaust survivor to return and represent the U.S. here,” Eisen says. “No one from my immediate family had returned since my mother fled Communism in 1949 and the symbolism of coming back here was just too unique an opportunity to pass up.” So, in January of last year, the Eisens packed their bags.

The Czech Republic is one of the most politically corrupt countries in Europe, and it has proven to be a challenging laboratory for Eisen’s knowledge. (Prior to joining the Obama Administration, he helped found Citizens for Responsibility and Ethics in Washington, a liberal answer to right-wing legal watchdog groups like Judicial Watch, which spent the 1990s hounding the Clinton Administration with lawsuits.) “Doing [private] business in the Czech Republic is very similar to doing business in the U.S.,” says Weston Stacy, the executive director of the American Chamber of Commerce in the Czech Republic. “But then if you’re talking about public procurement, doing business with the state is still a very non-transparent process.”

Early in his term, Eisen hosted a workshop on whistleblowing, inviting members of non-governmental organizations as well as representatives from the state, and he has followed that up with a series of seminars, bringing together anti-corruption experts from around the world to meet with Czech politicians and anti-corruption activists. “The Czechs have made confronting corruption a priority,” Eisen says. In November, Eisen hosted the World Forum on Governance, co-chaired by the American Enterprise Institute and Brookings Institution, which brought together about 100 representatives from around the world in the fields of finance, transparency, and anti-corruption to discuss best practices.

Transparency has proven crucial with one public tender in particular: the completion of the Temelín Nuclear Power Plant Station, a contract worth some $30 billion. The Czech government is entertaining bids from the United States (Westinghouse), France (Areva), and Russia (a state-owned conglomerate called Atomstroyexport), and the competition is widely viewed as a battle between those who want to keep the country oriented toward the West and those, like President Klaus, who are looking east toward Moscow. While French President Nicolas Sarkozy and Russian Prime Minister Dmtiri Medvedev have aggressively lobbied Prague, the job of representing Westinghouse has been left to Eisen. “Before, what you saw was a lot of lobbying by the Russians and some degree of lobbying by the French but almost a complete absence of lobbying by Westinghouse or the U.S. government on behalf of Westinghouse,” Stacey told me. “Since Ambassador Eisen’s arrival, the U.S. part of the bid has been substantially improved.”

***

The first member of his immediate family to attend high school, never mind university, Eisen was raised in southern California. After graduating from Brown, he worked for the regional office of the ADL before heading east for law school at Harvard. His father, who left Poland in 1929 and who passed away when Eisen was a teenager, ran a hamburger stand in Los Angeles and struggled to make a living. It was a very typical first-generation immigrant story; he has often said that his parents worked like the “Israelites in Egypt.”

Eisen shares that work ethic. Yes, he attends galas and cocktail parties, enjoying the role of an American emissary in an enchanting European capital, but he also keeps a frenetic schedule of public appearances, meetings with government officials, and has started his own blog on the embassy’s website and for leading Czech newspaper DNES. (He says the president reads it.) Last year, he visited the Czech contingent of the NATO mission in Afghanistan, for instance, and he’s taken a keen interest combating extremism, as demonstrated by his involvement in the Bátora affair. David Ondracka, the head of Transparency International’s office in Prague, says that Eisen is “the most visible figure among the diplomatic corps.”

Up until last month, however, it was unclear if Eisen would return to the job. In the fall of 2010, soon after Obama announced his choice of Eisen to be ambassador, Republican Sen. Chuck Grassley of Iowa placed a “hold” on the nomination. Grassley’s opposition stemmed not from any lack of qualification on Eisen’s part or his policy views, but rather his role, when serving as White House ethics watchdog, in the firing of Gerald Walpin, for his role overseeing volunteer programs like AmeriCorps. Grassley alleged that the White House and, by extension, Eisen, attempted to obscure their political motivations for firing Walpin, who had initiated an investigation of Sacramento, Calif., Mayor Kevin Johnson, an Obama ally, over accusations that he misused federal funds while heading a California charter school.

In a letter to Congress, Eisen explained that the decision to fire Walpin was due to his behavior at a corporation board meeting, in which he appeared “confused, disoriented, unable to answer questions and exhibited other behavior that led the Board to question his capacity to serve.” Yet Walpin’s defenders insisted that he was fired for political reasons—and Walpin was happy to oblige. Immediately after losing his job he appeared with Glenn Beck, who compared Walpin’s treatment at the hands of the Obama Administration to that of blacks in the segregated American south, claiming that Walpin had been fired because “he wouldn’t sit in the last row of seats; he wouldn’t get up from the counter.” Rather than continue without an ambassador to the Czech Republic, Obama sent Eisen to Prague via a recess appointment in December 2010. A year later, as Eisen’s term was approaching its end and Grassley showed no signs of lifting his hold, Eisen wrote a letter of apology, and Grassley allowed the nomination to proceed. On Dec. 12, Eisen was confirmed by the Senate, 70-16.

***

Two days after the death of Vaclav Havel on Dec. 18, Eisen hosted a Hanukkah party in his official residence. Among those in the crowd were David Cerny, a Czech of Jewish descent and the country’s most famous living artist, and Alan Dershowitz, whom Eisen worked for as a research assistant while at Harvard and who was visiting Prague with his granddaughter. “Our union was made in heaven,” Dershowitz told me. “He was a natural guy for me to hire because he was brilliant and shared many of the same liberal democratic, pro-Israel values that I did and that he still represents.”

Eisen’s palatial home once belonged to Otto Petschek, a German-speaking Jew and one of the wealthiest men in inter-war Czechoslovakia. Petschek died in 1934, and his family fled the country in 1938, right before the Nazi invasion. After the war, the U.S. government purchased the estate, and during the Cold War it became an important meeting place for dissidents, Havel included. Eisen arranged for one of Petschek’s daughters, now living in New York City, to address the crowd via webcam. As waitresses passed out potato latkes on silver platters (an observant Jew, Eisen had the residence kitchen kashered), he took the microphone to welcome his guests. Pointing to the large, decorated tree across the room, he remarked that it was “my first Christmas tree.”

Living in the building that once hosted the Nazi occupation forces has a special resonance for Eisen. He is the only member of his family to return to the Czech Republic since World War II. “Returning to a place where my family, and so many other Czechs and Slovaks, were oppressed by the Nazis and the Communists, was not without its challenges. Particularly the first weeks of living in my residence,” he told me. Not long after moving into the house, he found a swastika and a Nazi inventory number attached to an antique table in the foyer; seeing it was “a stab in the heart.”

He attributes his ability to overcome the initial trauma to his Jewish upbringing and religious observance. “Intellectually I recognized that my return represented a triumph over evil, but it took a little while to experience that triumph emotionally as well,” he said. In a speech last summer renaming the street outside his residence after Ronald Reagan, Eisen wowed (and surprised) the audience of conservative heavyweights with his praise for the 40th president. It was a genuine reflection of his centrist political sensibility and a worldview that was formed by two parents who experienced the worst horrors of the 20th century, only to discover the promise of freedom and acceptance in the United States. “As a child, my mother told me about growing up in the newly independent Czechoslovakia led by President Masaryk, about the horror of the Nazi occupation, and about the brief flowering of freedom after the war, only to have the Communists take over,” he says. “So, I experienced that history vicariously, and it’s fundamental to who I am and to everything I have ever done.”

Every Shabbat evening when he’s in Prague, Eisen worships at the city’s Altneu Synagogue, one of the oldest operating synagogues in the world and a place where Jews have been praying since the late 13th century. “My ancestors certainly prayed here when traveling through Prague—although as far as I know I am the first one in the family to earn an assigned seat,” he says. “After the pogroms of 1389, the walls were splashed in blood, which was left untouched for about two centuries. It was finally painted over in the 16th century, but I sometimes debate with other worshipers whether traces can still be seen. In any event, it seeps through in memory and consciousness, and yet here we still are.”

James Kirchick, a visiting fellow at the Brookings Institution, is a columnist at Tablet magazine and the author of The End of Europe: Dictators, Demagogues and the Coming Dark Age. He is writing a history of gay Washington, D.C. His Twitter feed is @jkirchick.

James Kirchick is a Tablet columnist and the author of Secret City: The Hidden History of Gay Washington (Henry Holt, 2022). He tweets @jkirchick.