The July 18, 1994 bombing of Israeli Mutual Association, known by its Spanish acronym AMIA, was the deadliest terror attack in Argentina’s history. It left 85 dead and injured hundreds in Buenos Aires, but its perpetrators, and their true motives, have never been fully revealed. The following are excerpts from Argentinian journalist Daniel Santoro’s book-length exposé, Nisman Must Die.

In 1989, soon after getting his law degree from the University of Buenos Aires and being a protégé of José Nicasio Dibur Natalio, Alberto Nisman was named assistant secretary of Provincial Court No. 7. Significantly, his immediate supervisor was Santiago Blanco Bermúdez, who subsequently became the lawyer for Argentina’s Secretariat of Intelligence (SIDE). From the Provincial Court, in 1988 Nisman rose to federal court, where the trial would be held for the 1994 bombing of the Israeli Mutual Association (AMIA) in Buenos Aires. In 1995, again with Dibur’s pull, Nisman was named federal prosecutor for the City of San Martín. A prosecutor who worked with him in those years described him as “a working machine, meticulous, intelligent and ambitious.” He also taught criminal procedural law and co-authored Manual de Derecho Procesal Penal (Handbook of Criminal Procedural Law). But his special qualification for a case in which the majority of the AMIA bombing victims were Jews was that “his surname was Jewish”—or “Russian,” as Jews in Argentina are often called because the first wave of Jewish immigrants spoke Russian.

In mid-1997, lead prosecutor Eamon Mullen bumped into Nisman at the Retiro courthouse and asked him, point blank: “Are you interested in taking on the AMIA bombing?”

Mullen suggested to Attorney General Nicolas Eduardo Becerra that he should beef up the prosecutorial team preparing the oral arguments with Nisman. Becerra answered: “I’m sold.”

The prosecutorial team complete, Nisman concentrated on what was called the AMIA bombing “brigade” file, which investigated Buenos Aires police accused of providing the terrorists with the Renault la Trafic used as a car bomb. [Prosecutor José] Barbaccia investigated the dis-assembler of stolen vehicles, Carlos Alberto Telleldín, and Mullen reconstructed the planning of the assault that left 85 dead and 300 wounded.

At first, Nisman worked out of an office at the headquarters of the anti-terrorist unit of the federal police (DUIA) on the part of the indictment he was assigned. The same intensity he invested in his work fueled in him, as in many men, a sexual addiction that the SIDE exploited to manipulate him. At the DUIA they also remember Nisman because beautiful women students would come around asking for him. The SIDE once “fabricated” an invitation to travel to a fictional anti-terrorist congress in Miami so he could travel with one of those girlfriends. He took that trip, even though he was warned that if he did “the SIDE will have you by the balls for life.”

His ambition and womanizing aside, the “Russian” was an evidence-extracting and loose-end-tying machine. By now it was 1999, and the principal prosecutors Mullen, Barbaccia, and [Miguel] Romero were on the verge of requesting the case be moved from the pretrial phase to an oral and public court, in which plaintiffs had to be revealed by their signature.

“I want to sign,” Nisman volunteered enthusiastically. “Sign away, Russian, sign away,” answered Mullen.

Meanwhile, the AMIA prosecutors learned that an attractive woman lawyer had filed a charge of sexual harassment against Nisman. His judicial colleagues were skeptical until they heard the voice recorded on the accusing lawyer’s phone; it was Nisman’s. Thanks to judicial bureaucracy and perhaps favors from cronies in the court system, the statute of limitations had lapsed, and the charge was filed away.

As a member of the congress’ Bilateral Commission on Monitoring the Attacks against the Israel Embassy (1992) and the AMIA (1994), Cristina Kirchner was a virtual nonpresence. But in 2001, after the testimony of Judge Galeano’s former secretary Claudio Lifschitz, she abruptly went from supporting the magistrate to demonizing him. After that, she arrogantly and vehemently rejected the “Iranian connection” and talked up the investigation of a “Syrian connection.”

Back then, Telleldín and the local police were thought to be the attacker’s “local connection” and the Iranians were thought to be the planners, known as the “international connection.” According to Galeano’s indictment, the attack with 300 kilos of ammonal was allegedly carried out by a commando of Lebanon’s Islamic Jihad under Hezbollah, which was financially and militarily backed by Iran in its war against Israel. Galeano saw the bombing as payback for Israel’s having killed a Hezbollah ayatollah and his son. According to Galeano, the order to attack in Buenos Aires and the necessary intelligence to mount the attack came from Iran.

In December 1997, congress approved its first report in which Cristina Kirchner defended Galeano’s work on the AMIA case. She also wrote her own, even more glowing, report calling for Galeano to also head the investigation of the 1992 Israeli Embassy bombing, which was moving nowhere. Cristina wrote that “if the results until now are not what were expected, the bombing not yet solved, recognition is due for the work carried out by Judge Juan José Galeano and the prosecutors Eamon Mullen and José Barbaccia in the investigation against the obstacles described in this report.” In 1998, in the investigatory commission’s second report, Cristina had no criticism to level at the judicial investigations and signed the majority opinion with the block of Peronist party liners who answered to Menem; her husband, Néstor Kirchner, as governor of Santa Cruz, was a Menem supporter. In 1999, the Judicialist Party promoted the presidential ticket of Duhalde and Palito Ortega and, on the provincial level, Néstor Kichner sought his third term as governor of Santa Cruz. Both Kirchners now backed Duhalde, who would be running against Menem. In 1999, a full session of congress approved that second report on the investigatory commission.

In contrast, congresswoman Elisa Carrió did raise questions: “My long judicial experience leads me to take a critical view of Judge Galeano’s performance,” she explained. Before being introduced to politics under the wing of Alfonsín in 1994, Carrió had been legal secretary of the federal court of Chaco. “I didn’t catch in the Bicameral Commission’s report an aforementioned examination of Judge Galeano’s performance, no better than the accomplishments of the supreme court on the bombing of the Israeli Embassy,” she added. “So that, without pretending to obstruct or question the Bicameral Commission’s work, I believe the omissions on Judge Galeano’s performance should be investigated.”

In 2001, the investigatory commission released its third report in which today’s Madam President concluded that Galeano’s investigation was “producing no satisfactory results” and raising “shades and doubts” about the intelligence agencies. She demanded a more thorough investigation of the “Syrian connection.” Strangely remarkable that no one followed up on this lead in which, viewed objectively, a suspect—Kanoore Edul—couldn’t explain the coincidence of his being in contact with Islamic fundamentalists, with the seller of the car bomb, and other highly suspect actors in this case. Cristina put all her money on the “Syrian connection,” not budging since then, and targeted Edul, a textile businessman with a history of alleged swindles, who before the bombing, in answering an ad published in Clarín, called Telleldín about a Renault la Trafic. Cristina referred to a “Syrian connection” because, like Menem’s, Edul’s family came from Yabrud, Syria, among other family ties.

Cristina Kirchner shifted to the theory that the masterminds of the AMIA bombing were not Iranian but Syrian after hearing testimony from Claudio Lifschitz, Galeano’s former clerk—a man who had other interesting secrets to hide. A former intelligence agent of the federal police, a “pluma [feather]” as they’re known in police slang, Claudio Lifschitz was the key witness who provided the first clues to SIDE’s 1966 secret payment of $400,000 to Carlos Telleldín, and reported on other alleged irregularities in Galeano’s investigation, a case that came to be called AMIA II.

Lifschitz had been recommended to Galeano in 1995 by the then director of the DUIA, Superintendent “Fino” Palacios. Galeano relied on the DUIA and the branch of the SIDE known as “Sala Patria [Fatherland Hall]” directed by Alejandro Brousson, which was pushing aside Sector 85 under Antonio “Jaime” Stiuso, in an episode of the Argentine intelligence community’s incessant internecine warfare. “Fatherland Hall” was in political ascent, having captured the former No. 2 of The People’s Revolutionary Army and the planner of Tablada regiment seizure. Stiuso’s group had lost influence after the 1994 AMIA bombing: his charge was to track the Iranian Embassy staff, who slipped through his hands. After that screw-up, Stiuso harbored an enormous resentment toward Galeano.

After advising Cristina, Lifschitz went on in 2007 to become attorney for the former SIDE agent Raúl Luis Martins, who ran VIP cabarets in Cancun, Mexico, and in Buenos Aires, which were accused of being fronts for prostitution. Lifschitz met his ex-wife, Beatriz Toribio Astorga, at the Intelligence Secretariat (SIDE). She later resigned, divorced her agent-lawyer and affirmed that her ex-husband “was a partner in some dealings with a member of the SIDE named Martins” who was “reputed in Cancun, Mexico, to traffic in white women destined for prostitution.” Lifschitz gave a counter version. “Martins asked me to change my testimony that (Menem’s former Minister of the Interior, Carlos) Corach was covering up the AMIA affair. Because I refused, they started to perform a human sacrifice.”

Months later, Lifschitz resigned his job with Martins, returned to Buenos Aires, and demanded a fee of ARS $1,200,000 for consulting between 1999 and 2006. In a labor lawsuit to which I gained access, he claimed that in Cancun Martins owned the cabarets The One and Maxim and a list of Buenos Aires clubs. Then he added that someone had planted “false accusations of prostitution against me.” In 2008 he made it to the front pages again, claiming to have survived a hail of bullets, allegedly from a band of agents led by “Lauchón Viale–a friend of Martins and a deputy of Stiuso,” and he showed where, after he went down, they carved on his back “AMIA.”

The bad news didn’t end there. On the one hand, the B.A. federal court prosecuted him for revealing state secrets in his book AMIA, por qué se hizo fallar la investigación (AMIA, Why the Investigation Was Allowed to Fail), which he wrote in 1997 after resigning from Galeano’s [office] during a six-month stay in New York, paid by “newspaper owners” never identified for “reasons of confidentiality.” He wrote the book after the allegations regarding Telleldín’s video, in which a payment of US$400,000 dollars was discussed, and that just happened to fall in the hands of Mariano Cúneo Libarona, attorney in the AMIA case for Police Superintendent Juan José Ribelli. On the other hand, Lifschitz’s ex-wife Beatriz Toribio Astorga affirmed in a sworn statement, that he received “a small fortune” for having stolen the video presumed to have recorded Galeano conversing with Telleldín about the payment of “400,000 dollars for author’s rights” for the writing of a book, which in reality was the secret payment from SIDE. Lifschitz denied both allegations.

The historic AMIA bombing trial began in federal oral court three on Sept. 23, 2001, with a request for a minute of silence from Pablo Jacoby, lawyer for Active Memory, an association of some of the relatives of the victims of the attack. “For those who died at the AMIA, at the Israeli Embassy, and the recent attacks in the United States.” Thus the homage included those who died in al-Qaeda’s attacks in the United States. The boring but obligatory readings of the evidence to the accused took up the hearing’s first day.

Some days later, with the support of an enthusiastic Nisman, Mullen and Barbaccia read the charges. They described the explosion as “a deafening sound, a hurricane wind, a terrifying bang and immediately a quake, a cloud of dirt … strewn corpses, an orange light, screams of pain and anguish, people wounded and human remains self-prioritizing before the stunned stares of observers, the intolerable concept of death.” Then they identified the 85 victims by their registry number at the judicial morgue and explained the cause of death of each. Family members reacted emotionally with every name called out that belonged to a relative. Luis Czyzewski, one the most determined and coherent members of the Association of the Families of the Victims, could not contain tears and later told the press: “For the first time I learned how my daughter Paula died.” According to the autopsy, his daughter suffered multiple traumatic blows resulting from the AMIA building’s collapse.

‘What’s at stake here is whether humans are no longer secure and fanatics will govern the world or if the law and the rule of law will prevail.’

Three months later, the Comodoro Py Court House hearing room was practically without journalists or audience. After attending the hearings, the president of the World Jewish Congress, the American rabbi Israel Singer, told the press, “It would appear that Argentine society is comfortable with indifference. This room should be full of people demanding justice because this is a test that is overdue yet historic. For what’s at stake here is whether humans are no longer secure and fanatics will govern the world or if the law and the rule of law will prevail.” Moreover, Singer assured: “In the United States, this case is being followed with great interest because the bombing of the AMIA wasn’t a crime perpetrated at the local level; rather, it was a preamble to the attacks on Sept. 11.”

Public attendance had declined by the end of 2001 because Argentines were steeped in political and economic crisis. The De la Rua administration had come undone. Five interim presidents had to be appointed until Duhalde managed to take the country’s reins and achieve enough stability to permit a call for elections in 2003. The presidential changes indirectly hurt the AMIA trial, owing to expected reappointments of SIDE heads and internal power struggles in that dark intelligence organization and among the security forces assigned to the judges of the investigation.

Meanwhile, the AMIA oral arguments proceeded slowly. In August 2003, in the Kirchner administration’s first months, the mysterious appearance of two café receipts became the evidence that proved the controversial payment. Agent Isaac García had turned them in to the SIDE administration office—after his taking part, in July 1996, in the secret handover of $400,000 to Carlos Telleldín’s wife, Ana María Boragni–so he could be reimbursed for his expenses. On the receipts appear García’s name, the day and hour, as well as the address of the café located near a bank in the Buenos Aires district Ramos Mejía, where the first secret payment was made to the wife of the man accused of preparing the used Renault la Trafic as a car bomb.

Who had kept those receipts for the past seven years? They showed up mysteriously in August 2003. On seeing them, the former head of SIDE and then Kirchner’s right-hand man, Sergio Acevedo, met with García, who revealed having taken part in a “special operation,” a component of which was making the payment. Intelligence law does not require him to account for or record payments “to informants” in special operations. That’s why there was no record, until that moment, in Medem’s bookkeeping on the SIDE. Moreover, following an intelligence rule of thumb, all the evidence not mentioned in the official report had to be destroyed because the payment was understood to be a state secret.

Having the receipts, Acevedo immediately put García on the stand to testify. The café receipts stayed in the case file submitted to the oral court trying Telleldín and ex-Police Superintendent Juan José Ribelli, among others. García’s testimony was made possible owing to the Kirchner decrees that lifted the secret that had protected Intelligence (SIDE) activities. Following García’s revelation before the oral court, other agents feared prosecution and added more details on the payment. Retired Major Alejando Brousoon, former No. 1 of “Fatherland Hall,” testified about that payment and elaborated on more intrigue, destroying the SIDE’s vaunted “code of silence.”

My sources from the intelligence world figure that those receipts were probably being kept apart from any official records, in some agent’s personal files. Their sudden appearance resulted from a fierce internal struggle in the organization, which was itself at odds with both the federal and Buenos Aires police. The retired army Major Brousson was director of the SIDE counterintelligence unit that oversaw Fatherland Hall, created in 1996 by the former SIDE director Hugo Anzorreguy and supervised by Patricio Finnen, who had won Galeano’s trust. His rival Stiuso had stayed away from the AMIA case until December 2001, when the head of SIDE, Carlos Becerra of the Radical Party, raided Fatherland Hall headquarters with armed retired police. Finnen was allowed to leave the premises with only what he was wearing.

Stiuso’s internal enemies in the SIDE had accused him of having made “excessive expenditures” in his secret operations and of allegedly having set off “a false alarm” about a terrorist attack against the American embassy in Asunción, prompting the landing in that capital of 70 CIA agents, who returned to Washington empty-handed. The preventive operation cost “$7 million,” affirmed an ex-SIDE agent to this author. Brousson, for his part, was accused of having made a newspaper publish the name of Stiuso’s daughter, who works for the federal judge María Servini de Cubría. When Duhalde became president, Attorney General Carlos Soria made it one of his first acts “to sack Finnen and Brousson” and shut down Fatherland Hall. The new government also opened a second inquiry into the filming of an interview between Galeano and Telleldín on April 10, 1996.

In that video Galeano, is seen speaking to Telleldín about the payment for the supposed rights to a book, to which Telleldin responds:

“If I testify, you, doctor, don’t dare investigate the Buenos Aires police.”

“Secretary, bring me the ‘Brigades’ case on Ribelli’s affairs,” Galeano answered to show that he had no fear of “the black boots.”

In the video, an employee brings in a very thick dossier, and the surprised Telleldin gets up, raises his arms, and says an expletive.

Brousson had filmed that scene at the request of Finnen, who always held that Ribelli’s people received the van from Telleldín—and, to make another sale, without knowing it, sold it to someone connected to the terrorists.

The head of the SIDE under Duhalde, Miguel Ángel Toma, had chosen Stiuso to produce the report that he submitted in January of 2013 to Galeano, which argues that the van (meaning the la Trafic) had been received by members of the local Muslim community and not Ribelli’s people. After the receipts suddenly appeared, President Kirchner signed a decree that lifted the restriction on questioning another 14 SIDE agents by the then director of counterintelligence, Stiuso. Before he did, one of his lawyers approached Marta Nercellas, an attorney for the Delegation of Israeli-Argentine Associations, and asked to speak to her alone in the corridor of the Comodoro Py Court House to extend a hushed threat:

“Are you thinking of cross-examining my client?”

“Yes, that’s my job,” answered Nercellas.

“Keep in mind that we know every detail about your personal life.”

“I’d be glad if you found something interesting,” answered the lawyer with a smile as she turned and walked away.

Stiuso said that according to his investigations, the “local connection” of the terrorists who blew up the AMIA in 1994 included the former cultural attaché of the Iranian embassy, Mohsen Rabbani, and the Argentine businessman of Syrian origin, Alberto Kanoore Edul. Before that testimony, Stiuso had spoken of an “agreement” between Judge Galeano and Intelligence’s “Fatherland Hall” to accuse the Ribelli-led Buenos Aires police.

Rabbani was a cleric to whom Iran had given diplomatic immunity six months before the bombing and who remained in Argentina until 1998. Later Galeano ordered his arrest as a key player in the international connection. “Galeano would hear nothing about a Lebanese Hezbollah connection. … He spoke of the Iranians and Lebanese as two when the whole world knows they’re one,” underscored Stiuso. He added that “when the FBI agents came to our offices, they were surprised by only one thing: that Edule was not in custody.”

Galeano’s other evidence was the phone calls made on the accused’s cellphones. “Every magnetic system can be tampered with,” said Stiuso, sowing doubt in any technician’s determination of the locations of the Buenos Aires police cellphones on the day that Telleldín gave them the van, which was later used as a car bomb. According to Stiuso the la Trafic was handed over on Sunday, July 10, 1994—eight days before the bombing—but sometime that afternoon, not in the morning. In other words, they had eight days to arm the bomb with 300 kilos of ammonal (a fertilizer commonly used in bomb-making), install a mechanism to control the explosion and new shock absorbers, among other modifications, not to mention gather the preliminary “intelligence” on the vicinity surrounding the AMIA. Stiuso’s account admits that once it became known that Telleldín had provided the van for the bombing, the Buenos Aires police kept their sights on him but mainly to see if he could serve the police by reselling confiscated stolen cars, not because of the bombing.

For his part, on Nov. 23 Alejandro Brousson, former director of Fatherland Hall, testified that Telleldín was paid in the Comodoro Py Federal Court House car park by Finnen after talking with Judge Galeano, and that Finnen was given the cash by Anzorreguy. “I have no doubts that this was the SIDE at work because that’s what I was told by my boss, Don Hugo,” said Brousson, referring to Anzorreguy. The payment is serious evidence because the first installment of $200,000 was put in the hands of Telleldín’s wife, Ana María Boragni, the same day her husband chose to testify against the ex-Buenos Aires police before Judge Galeano.

Brousson confirmed being present in chambers on the famous day of the judge’s meeting with Telleldín—which, for security reasons, was taped: “I heard about some business involving the purchase of a book. The judge comes over to me and asks, ‘What do you think?’ A secure payment is always possible, I answered.” Later he testified that the recording—made on a tiny spy camera in an attaché case–was later viewed at the SIDE by Galeano, Anzorreguy, Finnen, and Rodrígo Toranzo, former secretary of intelligence.

The receipts and the agents’ testimonies opened a silver path to the Syrian connection that the first lady was advancing. In her testimony in December 2003 at the AMIA trial, then-senator Cristina Kirchner had completed and amplified her turn toward the Syrian connection. Now she wasn’t just a senator but the wife of President Néstor Kirchner, and his likely heir apparent. In the 40-page transcript of her testimony, to which I had access in the court archives, she was insistent: on the bicameral commission, “I wasn’t the only one who believed in the Syrian connection,” adding that on the commission there “hovered an understanding” that ex-President Carlos Menem did not “encourage the clarification” of the bombing, in order to protect Kanoore Edul.

Cristina also commented that during the commission’s hearings, Anzorreguy asked her about the book El Peso de la Verdad (The Weight of the Truth) by Domingo Cavallo, which reports on a meeting between Menem allies and Lybian or Syrian authorities to discuss broken promises. The book refers to Menemist promises to Qaddafi who, in exchange for money to fund Menem’s 1989 run, was to be sold the intermediate-range Condor II missile, considered a weapon of mass destruction because of its capacity to deliver a 1,000-kilo payload. The suspicion regarding Syria was that the Menemists had offered to sell the Syrian regime the prototype of the Argentine nuclear reactor called Carem, but that after Menem’s aligning with Washington, the reactor was never sold.

Throughout her testimony, Cristina insisted several times that she assumed a “critical stance.” “For me, the fact that so many things have taken place as they have and that nobody has been punished cultivates an illusion of impunity among the very the intelligence and security agencies [who are responsible].”

Argentina’s secret diplomatic relations with Iran only became public with a pact signed in 2013. But there was already movement in the nation’s highest penal court that mirrored the 180-degree turn of Cristina’s foreign policy. Her supporter Judge Ana Figueroa requested in writing the AMIA and related cases, even though the law forbids magistrates from being able to choose their cases.

While the government secretly negotiated with Iran, Figueroa asked her judicial peers to hand over the 13 cases linked to AMIA. Among them were the cases of ex-judge Galeano and the Syrian-born businessman Edul, whom Cristina accuses of covering up ex-president Menem’s Syrian connection.

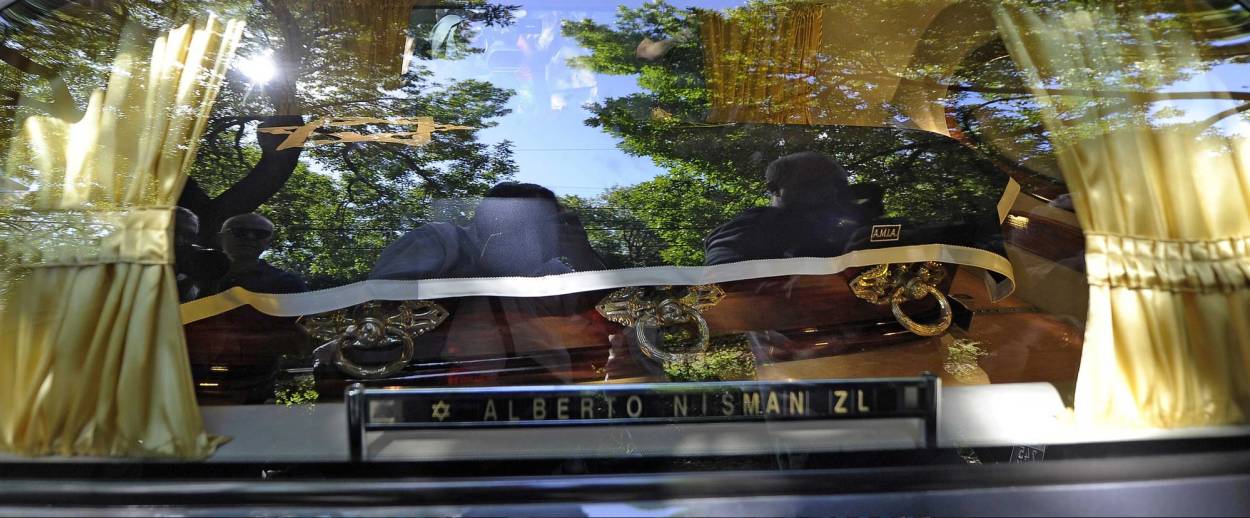

March of Silence called by Argentine prosecutors in memory of their late colleague Alberto Nisman in Buenos Aires on February 18, 2015. (Photo: Juan Mabromata/AFP/Getty Images)

The federal court is divided into two salas (courtrooms) that received cases by lottery. Historically the appeals part—the one hearing the AMIA bombing and related cases—is Courtroom II. Figueroa was appointed permanent chair of Courtroom I. Nevertheless, on Dec. 13, 2012—45 days before Ambassador Héctor Timerman would sign the pact with Iran in Ethiopia—Figueroa sent an internal memo to the then-court president Pedro David in which she requested that, to guarantee “an adequate service of justice,” she continue “to participate in every one” of the cases related to the AMIA bombing. A few days after the Iran pact was signed, Figueroa wrote a note, dated Feb. 18, 2013, asking the court president “not to act on her request” because she hadn’t attended the hearings and because her request could be misconstrued as a “possible presumptuousness against the right of the sitting judge.”

On April 4, 2013, lawyers for the AMIA and the DAIA, and eventually the prosecutor Nisman, moved to establish the Iran pact’s unconstitutionality, exasperating the government and affecting every branch of justice. First, the federal judge Rodolfo Canicoba Corral–then lobbying to get his son appointed federal judge–declared the pact constitutional. The AMIA/ DAIA and the prosecutor Nisman separately filed to overturn that decision. Courtroom I agreed that it did violate the constitution and thus stayed its implementation.

Then, in May 2014, the government appealed the decision, arguing that “procedural norms were violated,” that the case was not even “a judicial matter” being an Executive Order and even then the issue is moot because the pact was not yet in effect. The appeal went to Courtroom II, where every one of its judges recused or excused himself for different reasons. Three replacements were named: Figueroa, Luis Cabral, and Juan Carlos Gemignani.

In April 2015, Cabral and Figueroa, at the time candidates for the supreme court, voted for the pact’s being re-translated into English. Gemignani dissented, deeming it an unnecessary delay. The original memorandum signed by Argentina and Iran was already in three languages: Spanish, Farsi, and English. Then Ángela Ledesma, president of the entire court, ordered to inquire if the U.N. had registered the accord, entailing a long bureaucratic process. Ledesma then took a leave of absence. Gemignani immediately assumed the interim presidency and declined to act on Ledesma’s order—which favored the government—for its being “impertinent, unnecessary, and obstructive.”

Pope Francis, despite his doubtless monitoring of the world’s religious problems, wars, famines, migrations and other crises around the globe, is kept informed on the political, social, and economic situation of Argentina. His chief concern since becoming pope in March 2013 was that President Cristina Kirchner finish her term normally, that the social situation remain peaceful, and that she take measures to stop the rise of drug trafficking and police corruption. He received her for those reasons, to sway her—through her former chief of staff, Sergio Massa—despite Cristina’s having stood in the way of his chance of being elected the supreme pontiff after the death of John Paul II.

On June 7, 2015 Cristina had her fifth private audience with Francis. Only 15 people accompanied her but she met with the Pope alone, and afterward claimed that nothing was spoken about Argentine politics. But my sources close to the pope revealed that “Cristina spoke an hour and 15 minutes,” and revealed that, for the 2015 elections, she “planned to request the resignation of all the presidential candidates of the Frente Para La Victoria Party, with the exception of Scioli,” and then “proceeded to defend the Iran pact and give her theory that Nisman’s death” was an international conspiracy targeting her. In reply, the pope asked about her son Máximo and her expecting daughter Florencia, not a word on Iran nor Argentine politics. But he was put off that, among her reduced party, Cristina should bring to the Vatican the leader of the Maritime Worker’s Union, Omar “El Caballo” Suárez, who had been prosecuted for delaying the docking of ships that didn’t pay a “donation” to his foundation.

Cristina, claiming she had anticipated the U.S.-Iran nuclear deal, sent Ambassador Timerman to ask the U.S. State Department if the agreement helped the Iranians charged by Nisman. In a “nonpaper,” the State Department answered that “in no way does the accord … have an impact or nullify Interpol’s Red Alert against General Vahidi as involved in the 1994 bombing in Argentina,” referring to the order sent out in 2006 by federal judge Rodolfo Canicoba Corral and requested by Nisman.

Madam President’s interview with The New Yorker journalist Dexter Filkins became major news. Warned of the magazine’s critical angle, the administration published the entire interview in a special supplement of the daily Página 12, later distributed by every pro-government media outlet. But few caught that Cristina had again publicly expressed her wish that Justice rule that the Iran pact is constitutional. Most important of all, Cristina said she expected her successor, understood as Scioli, to press forward with the Iran deal. Scioli’s efforts to get the federal court to close the file on Nisman’s charges speaks to his having agreed to do this before Madam President politically anointed him as the candidate of the Frente. “I end my term on the 10th of December,” Cristina told the interviewer. “Surely whoever succeeds me will have the intelligence and sufficient clarity of mind to achieve, perhaps, what I couldn’t. But it won’t happen by taking a causus belli to the U.N. Security Council [author’s note: i.e. what Nisman planned to do].”

Asked who the AMIA assassins were, Cristina reiterated that Nisman’s charges were part of a U.S. right-wing and Israeli conspiracy opposed to Obama’s nuclear agreement with Iran. She volunteered that should the Iran pact be found constitutional, she—and eventually Scioli—will ask Iran to ratify it in its parliament so Judge Canicoba Corral could interview the five accused Iranians and carry out other matters agreed in the pact.

When she was asked about the marketing firm Ipsos’ poll in January 2015, that 70 percent of Argentines believed Nisman had been assassinated and 82 percent saw merit in his charges of her covering up, she responded: “I don’t believe in polls. Nobody knows who’s being polled and where they publish the results. … Sincerely, I’ve heard that some Iranian commandos did it, I’ve heard that it was angry criminals, but I’ve never heard anybody say to me or can believe that I really had absolutely anything to do with this.”

Cristina had already won the fight against the dead prosecutor, meaning that she beat the dead man in the media battle to destroy the image of her public and private life. The debate over the constitutionality of the Iran pact was, therefore, in political terms, the last “fight” between Nisman and Cristina. Until now, it has not reached its final round.

Adapted from Daniel Santoro’s Nisman Debe Morir (Nisman Must Die), translated from the Spanish for Tablet magazine by Julio Marzán. Reprinted with permission. Copyright © Ediciones B, 2015. All rights reserved.