The Foreign Policy of the American Left

Second in a series on the American left: Michael Walzer and Bernie Sanders

This is the second part of an extended commentary on the American left. Read parts one and three.

I.

What does the American left believe about world affairs? Everyone knows what the American left believes about domestic affairs. The left believes that social conscience ought to be elevated into policy; extreme inequalities of wealth and social advantages ought to be narrowed; trade unions ought to be encouraged; idiotic bigotries ought to be combated; the rights of women, promoted; the rivers and forests, protected—and thusly, across a liberal and social-democratic terrain. Who opens a school, closes a prison, said Victor Hugo; and the American left agrees. But foreign policy is another matter.

It is difficult even to describe the texture of left-wing thinking on the topic. Michael Walzer has brought out a book called A Foreign Policy for the Left, in which he argues that, when people on the American left contemplate domestic affairs, they do so in a thoughtful, sober, and serious manner—or, at least, they make what Walzer considers to be an honest effort. But when those same people turn to world affairs, they slip into a different habit of mind, as if sliding from one lobe of the brain to another. The intellectual discipline loosens. The spirit of thoughtfulness fades, the information thins out. And downward plunge the well-meaning and otherwise upright leftists into the cups of faraway fantasy and political inebriation.

Naturally these habits and traits do not adhere to every last person with a left-wing orientation. The American left has its learned specialists on world affairs, who maintain their political commitments and, even so, remain sober, studious, lucid, grave, and admirable. But the broad left-wing public, as Walzer pictures it, attaches no particular importance to the upright specialists and their teetotaling expertise. The left-wing public prefers, instead, to adopt foreign-policy opinions merely by invoking a tiny cluster of assumptions or beliefs, amounting to slogans or prejudices, which are deemed to be true, and therefore stand in no need of specialists and analysis.

Walzer pictures the cluster of assumptions and beliefs as a default setting on a computer, which goes automatically into operation as soon as the machine is booted up. The question of world affairs arises, and the left-wing public responds by thinking: “Everything that goes wrong in the world is America’s fault.” No elaboration seems required. From that one assumption follow all the others. The assumption about everything being America’s fault carries the implication that American power, in addition to being sinister, is limitless; and the further implication that everyone else’s power adds up to naught. Alternatively, the assumption carries the implication that, even if American power does have limits, America’s arrogance does not. And, by failing to recognize the limits of its capabilities, arrogant America wreaks its damage by clumsily staggering from blunder to blunder. Less power for the superpower should be the left-wing goal, and more power for powerless international institutions. Whenever a terrible emergency becomes visible somewhere around the world, the responsibility for dealing with it should fall to the international institutions, and not to the unilateral, uncontrolled, piratical, and imperialistic United States.

It may be that, as Walzer observes, no one on the American left actually puts any faith in the abilities of the United Nations or the International Criminal Court or any other international institution. Yet the American left, in its default mode, looks to the U.N. and the ICC anyway, and this is odd. Walzer detects a touch of make-believe in the left-wing enthusiasm for those particular institutions, which he describes as a “politics of pretending.” A politics of pretending implies a dishonesty. In Walzer’s analysis, a streak of dishonesty, too, figures in the left-wing default.

Sometimes a broad public on the American left gazes upon authoritarian political movements and dreadful dictators in distant corners of the universe and likes to imagine that, far from being authoritarian or dictatorial, the movements and the dictators are boldly progressive, superior perhaps even to the U.N. and the ICC—though Walzer suggests that, in their inner thoughts, a great many people do know better. But they go on proclaiming their political fantasy, anyway, which amounts to an additional twist on the “politics of pretending.”

There is the spectacular instance of left-wing delusion about the Islamist political movement—the left-wing supposition that something has got to be progressive about the Islamists, even if the Islamists appear to be medieval reactionaries; and the further supposition that Islamism’s enemies among Muslims and non-Muslims alike must surely be the actual reactionaries, even when the enemies appear to be liberals and progressives. Here is a “politics of pretending” in a double-twist pretzel version. Walzer’s chapter on this theme, “Islamism and the Left,” brings him to the edge of his patience, though not beyond (given that inexhaustible patience appears to be a philosophical principle, for him).

Only, why would large numbers of idealistic-minded people on the American left want to engage in this sort of foreign-affairs make-believe? What is the appeal in it? The appeal is to avoid thinking about the world beyond the United States. The same American left that puts serious thought into social and economic conditions at home cannot be bothered to put any thought at all into problems and conditions abroad. “Leftist inwardness” is the spirit. It is a provincialism that calls itself idealism.

II.

Or so argues Michael Walzer in A Foreign Policy for the American Left. I can imagine that some of his left-wing readers will shake their heads in disbelief, or, at least, will pretend to do so. They will complain that he has drawn a cartoon, and not a very friendly one at that, and he has been unfair to people who do think about the wider world. Or they will complain that, in drawing his cartoon, Walzer has relied all too cavalierly on his vague impressions of the left-wing scene. Is there anything to that complaint?

It is true that Walzer’s research technique consists of talking to friends and attending meetings and reading magazines and surfing left-wing sites—though I cannot really imagine a better method. The method, as it happens, rests on a lifetime of left-wing experience. The general accuracy of his impressions ought to be, in any case, obvious at a glance. Some things are obvious, even if no one has pointed them out. Besides, Walzer allows an occasional confirming factoid to intrude upon his analysis. One of those factoids turns up, as if by coincidence, on the first page of his book. He pretends to make very little fuss about it. The factoid is immense, though. It is irrefutable. It is Bernie Sanders’ 2016 primary campaign for the Democratic Party nomination.

The Bernie campaign was a momentous event in the long history of the American left. It marked a turning away from the principal tactical idea of the radical left during the last half century and more—a turning away from protest politics in favor of electoral politics, where power is to be found. It marked a turning away from a main way of picturing life, which is through a mix of identity-politics grievances and fantasies about distant events, in favor of a classic leftism of economic grievances and working-class solidarities.

The question of world affairs arises, and the left-wing public responds by thinking: ‘Everything that goes wrong in the world is America’s fault.’

And yet, in regard to foreign policy, Bernie’s campaign conformed almost obsessively to the foreign-policy default position that Walzer has identified. Especially it conformed to the default’s most important aspect, which is a determined avoidance of foreign policy. Bernie’s opponent in the primaries ran on her foreign-policy credentials and achievements, which were, respectively, vast and middling. Bernie responded by offering a few bitter condemnations of the Iraq War, and by shuddering in horror at Henry Kissinger, and by criticizing his opponent for barely mentioning the Palestinians in her speech to AIPAC. But mostly he kept his mouth shut.

The political journalists expected Bernie to deliver a full-scale speech on world affairs, which they would have reported in detail. They insisted on it, after a while. Their insistence became news, for a moment or two. Or, if there was not going to be a speech, they wanted to know, at least, who were his foreign-policy advisers. Hillary’s foreign-policy advisers were said to number in the hundreds. Nobody knew who were Bernie’s, nor was his staff keen on revealing the names, which led to the supposition that maybe Bernie’s team did not exist.

Eventually his staff came up with a number of names, which made for a comic moment because one person after another who was said to be on the team denied being any kind of adviser at all. The distinguished name of Michael Walzer appeared on the list. But Walzer, as he has told me, had never been an adviser, except in the sense that one day, a couple of years previously, the senator called the philosopher, and they discussed Syria on the phone.

From Bernie’s standpoint, though, none of this mattered, and there was no reason to worry about the journalists and their demands. Crowds larger than anyone has ever seen in the modern American history of left-wing politics kept on sending in $27 contributions to his campaign. They did so because they wanted their candidate to go on banging his drum on matters of economics and corruption here at home. They wanted to hear about the possibility of radical reform. Everyone loved free college tuition. And, among his cheering supporters, there appeared to be not the slightest demand for Bernie to say anything at all about the world beyond America’s borders. Such was the historic campaign. Absolutely it was the proof that Walzer’s cartoon portrait of the climate of opinion on the American left is, in fact, accurately drawn—“a near-perfect illustration,” as Walzer puts it, of the American left and its position on foreign affairs.

Only, that was before the fateful day of Nov. 9, 2016.

III.

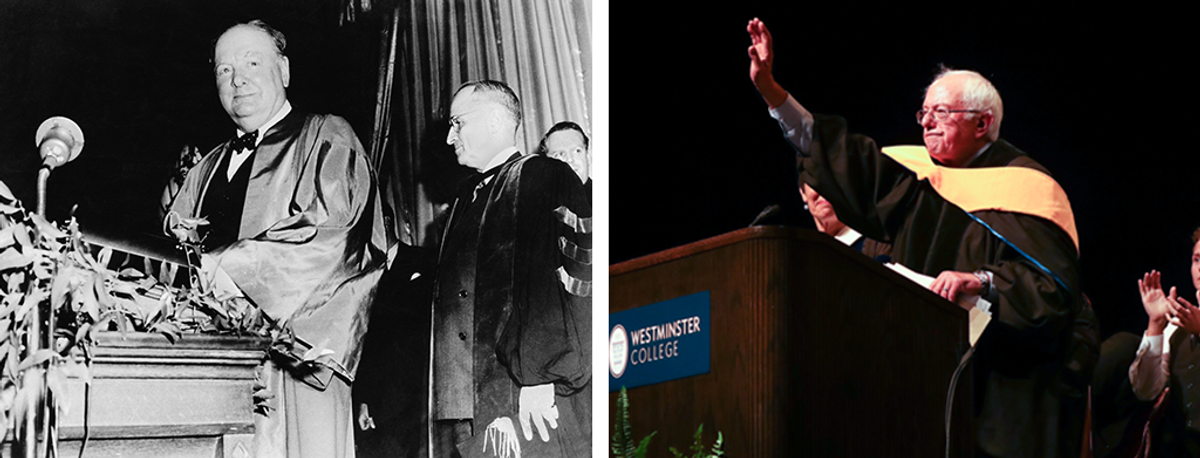

Afterward, the lights dimmed a little in America, and many things underwent a transformation, and among them was Michael Walzer’s prime example of the default position of the American left: Bernie Sanders, the “near-perfect illustration.” Bernie’s transformation was a matter of thought and reflection. He ruminated at length over his foreign-policy silence, or so we may gather. And, in time, he brought the silence to an end. He was voluble about it, too, and he did it twice: at Westminster College in Fulton, Missouri, in September 2017, which was the foreign-policy speech that everybody in the press had demanded in 2016; and again at Johns Hopkins, on Oct. 9 of this year, where the same ideas reemerged with greater simplicity. And in neither version did his views turn out to be what anyone would have predicted.

The appeal of the default position has always rested on a look of profundity—on a supposition that somewhere beneath the slogans and assumptions lies a bedrock of serious thought, a foundation of classical Marxism, perhaps, or a sober influence from the anti-colonialist theoreticians of long ago, or a layer of Christian reform from the social-gospel school. The supposition lends solidity to the slogans and assumptions. Only, the solidity does not exist, and neither does the bedrock—not for the broad left-wing public. There is no deeper philosophy. There is only the tiny set of unexamined default-position beliefs, afloat like dust motes.

And yet, the airiness of those beliefs turns out to have an unexpected virtue, which is flexibility. Someone who clings to the default position may declaim the slogans six days a week. But, come the seventh day, that same person, exhausted by his own dogmatism, may decide to entertain a further thought or two, oblivious or indifferent to the dangers of ideological inconsistency. And so it was with Bernie Sanders, in the course of the first of his foreign-policy addresses.

Dutifully in that speech he deployed the concepts and slogans of the default position. He rehearsed the miserable consequences of American military power, as shown by the Iraq War, to which he attributed the problems of the Middle East as a whole. He recounted the American arrogance in Iran, Guatemala, and Vietnam in decades gone by. He invoked the virtues of the United Nations and international organizations. He worked in a few calls for economic equality and a climate policy. But then, having demonstrated his left-wing orthodoxy, Bernie evidently felt that he was entitled to turn on his heel and append an additional reflection.

Westminster College in Fulton, Missouri, is the place where, in 1946, Winston Churchill announced the arrival of the Cold War by declaring, in a major address, that an “Iron Curtain” had fallen across Europe, separating the tyranny of the Soviet Union from the freedom of the West. Churchill was no longer prime minister, for the moment, but he was adored by the American public. And he was admired in the eyes of President Harry Truman, who accompanied him to the college auditorium and sat on stage throughout the oration. Churchill’s purpose at Fulton was to drag America out of its national “inwardness” into the larger struggle for a democratic civilization. He looked back upon World War II, and he pictured it (in this speech, at least) as an ideological struggle for democracy and human rights against the fascists. He wanted Americans to understand that, as of 1946, Stalin and the Soviets posed an equivalent challenge. He wanted the United States to resist. And, at Westminster College in September 2017, on that same auditorium stage, Bernie Sanders, having said all the right things to demonstrate his default-position bona fides, offered an extended salute to the internationalist and anti-totalitarian arguments of Winston Churchill.

This was not the default position of the American left. Not even historically was admiration for Churchill a left-wing sentiment. The American Socialist Party had shriveled into a wisp of a thing by 1946 or thereabouts, but out of the old party had emerged a scattering of individuals and political circles who added up to a faction or tendency, with institutional strength and a budget from the garment workers union and a few other corners of the labor movement. This was a social-democratic faction. The people in it regarded themselves as harder-nosed and better-informed on world affairs than the conventional liberals. And never would those people, the American social democrats, have chosen Winston Churchill as their hero. Churchill was a conservative. He was the enemy of totalitarianism, but he was the friend of British imperialism. If the social democrats had wanted to celebrate a hero or two, they might have looked to their own doughty selves, or to certain of their comrades in the British Labour Party or the Trades Union Congress. They might have settled for Harry Truman, who was, at least, a liberal.

Bernie Sanders in 2017 nonetheless applauded Churchill. Maybe it was the effect of standing on the historic stage. Still, he also ascribed to the United States a vocation to promote democracy around the world, and this was a point that, in 1946, the American social democrats, a good many of them, might have approved. His concept of democracy promotion was not a military one, but he did want to be serious about it. At the United Nations in September 2017, Donald Trump had delivered one of his many world-affairs speeches that failed even to allude to Russia’s intervention in the election of 2016. And in Fulton, Missouri, the leader of the American left said:

I found it incredible, by the way, that when the President of the United States spoke before the United Nations on Monday, he did not even mention that outrage.

Well, I will. Today I say to Mr. Putin: we will not allow you to undermine American democracy or democracies around the world. In fact, our goal is to not only strengthen American democracy, but to work in solidarity with supporters of democracy around the globe, including in Russia. In the struggle of democracy versus authoritarianism, we intend to win.

IV.

A year later, in October 2018, in his second foreign-policy address, the one at Johns Hopkins, the homages to Winston Churchill were gone. But something of the global sweep of Churchill’s instinct lingered behind, together with the impulse to see in the war against fascism a model for later challenges. In Bernie’s interpretation:

There is currently a struggle of enormous consequence taking place in the United States and throughout the world. In it we see two competing visions. On one hand, we see a growing worldwide movement toward authoritarianism, oligarchy, and kleptocracy.

He attached the word “axis” to the growing movement:

I think it is important that we understand that what we are seeing now in the world is the rise of a new authoritarian axis. While the leaders who make up this axis may differ in some respects, they share key attributes: intolerance toward ethnic and religious minorities, hostility toward democratic norms, antagonism toward a free press, constant paranoia about foreign plots, and a belief that the leaders of government should be able to use their positions of power to serve their own selfish financial interests.

He attributed global aspirations to the authoritarians, oligarchs, and kleptocrats. “The authoritarian axis,” he said, “is committed to tearing down a post-World War II global order that they see as limiting their access to power and wealth.” He took note of “a network of multi-billionaire oligarchs who see the world as their economic plaything.” He noted the role played by the American president:

While this authoritarian trend certainly did not begin with Donald Trump, there’s no question that other authoritarian leaders around the world have drawn inspiration from the fact that the president of the world’s oldest and most powerful democracy is shattering democratic norms, is viciously attacking an independent media and an independent judiciary, and is scapegoating the weakest and most vulnerable members of our society.

He saw a solution:

We need to counter oligarchic authoritarianism with a strong global progressive movement that speaks to the needs of working people, that recognizes that many of the problems we are faced with are the product of a failed status quo. We need a movement that unites people all over the world who don’t just seek to return to a romanticized past, a past that did not work for so many, but who strive for something better.

The speech adds up to a thumbnail sketch of world events, drawn with a black pencil and a sense of drama. I blink in admiration at the phrase “oligarchic authoritarianism.” It is a phrase out of Orwell’s character in 1984, Emmanuel Goldstein, who is the author of an anti-Big Brother tract called The Theory and Practice of Oligarchical Collectivism. But, really, isn’t “oligarchic authoritarianism” a pretty good description of Putin’s political system? Naturally the thumbnail sketch omits a few particulars, namely, the specific realities in each new troubled corner of the world. It says nothing about mad ideologies (apart from a passing observation that Saudi Arabia, “a despotic dictatorship,” “clearly inspired by Trump” in the current moment, has spent the last several decades subsidizing a “very extreme form of Islam around the world”). It offers not too much in the way of actual policies, apart from withdrawing America’s support for the war in Yemen and reducing the defense budget, which are conventional views right now in the Democratic Party. What would Bernie have us do, positively speaking? He does not say. I wonder how much work he has put into the programmatic details. But the speech is interesting not because of the details.

Everybody understands Trump’s “America First” slogan. It is an old slogan. He borrowed it from the isolationists of the America First Committee in the early 1940s, for whom “America First” meant an America that renounced the principles of democratic solidarity and therefore had very little reason to get involved in foreign conflicts—an America that exuded sympathy for the fascist regimes of Europe, and was none too keen on the Jews: an America that calculated its own interests narrowly. Trump’s version of the slogan in our own moment means pretty much the same thing, minus the special aversion for the Jews, except sometimes.

“America First” means an America that feels no obligation to defend democracy or democracy’s institutions around the world—an America that feels, instead, a sympathy for oligarchical authoritarianism, and upholds a cash-register view of world affairs: an America that regards idealism as deception. The slogan could not be simpler, and yet it expresses a larger philosophy, or something of one, anyway—a parched philosophy, selfish, unimaginative, and sulfuric with anger, but, still, a philosophy. And the philosophy allows Trump to ask the largest of foreign-policy questions. E.g., why should America stand up for its allies? Wouldn’t America be smarter to treat its allies as commercial partners, to be rejected or abandoned as soon as the cash flow goes the wrong way? NATO—isn’t it an anti-American scam? And all of this raises a question of a different sort, which is: What is the right way to answer those several points?

Hillary Clinton spelled out one way of doing so in her campaign book, with Tim Kaine, Stronger Together, in the section on foreign policy. America, in Hillary’s eyes, ought to stand by its allies. And America ought to be thoughtful and active and generous on climate, on trade, on women’s rights, and human rights. She laid out the positions in the Clinton style, which meant a laundry list of items, every one of them well-conceived, at least in my eyes. And yet, a laundry list may not be the ideal platform for addressing big questions such as: Why not adhere to a cash-register view of life? Or, in the degree to which Hillary did address the big questions, she did so mostly by invoking the major theme of her campaign, which was a cult of strength.

Only, what is the purpose of strength? In Stronger Together, she told us that safety was the purpose—quite as if the minimum goal of the world’s superpower (which is not to get attacked) should also be its maximum goal. “Safer Together” was the name of the foreign-policy portion of her book. “Security” was the running head at the top of each new page. She never quite explained why her version of safety was preferable to Trump’s.

The superiority of Bernie’s thumbnail sketch lies, I think, in his ability to point to things that are larger than a laundry list, and grander than strength and safety. The worldwide struggle for democracy and justice is his cause, and solidarity is his principle. His evocation of these things is not especially sophisticated, in an international-relations kind of way. The diplomats in his audience at Johns Hopkins (he spoke at a center for international studies) must have muttered to themselves, as he went on speaking, “This man could benefit from professional advice.” But there is something to live by, in Bernie’s cause and his principle. And the global grandeur is to the point. Precisely it addresses Donald Trump.

“America First,” in Trump’s version, sounds like a call for an American withdrawal from strife and conflict around the world, but everybody understands that, even so, something in the call is radical in the extreme, which means that, in its fashion, it commands a grandeur of its own. The call is for a return to the 1940s, this time in order to follow the advice of the America First Committee of those days. It is a call for America to dismantle everything that came out of the American victory in the world war, the advance for democracy, the international institutions, the notion of a democratic civilization.

And something in Bernie’s thumbnail sketch of world affairs likewise hearkens back to the ’40s—in Bernie’s case, to some of those same American social democrats whose example failed to stir him when he contemplated Winston Churchill, but who do seem to linger ancestrally in his universe. The people who came out of the old American Socialist Party, Reinhold Niebuhr and a few others, were the very people who led the battle of opinion against the America First Committee. Niebuhr and his comrades organized a committee of their own, the Union for Democratic Action, which was left wing and internationalist at the same time, in favor of “a two-front fight for democracy—at home and abroad.”

Their committee evolved into a larger organization called Americans for Democratic Action, with funding and political support from the social democrat unions, which meant David Dubinsky and the garment workers. And, in the Truman years, Americans for Democratic Action played a main role in generating the post-WWII concept, not entirely false or dishonest (even if sometimes false and dishonest), of an American commitment to freedom at home and around the world. The social democrats and their liberal friends in those organizations saw the world in ruin from the world war, and they saw America’s strength and the ideals that could be America’s, and they looked for a foreign policy that might accord with social-democratic or New Deal principles, an internationalist policy, democratic, pro-labor, anti-totalitarian, and broadly in favor of dismantling the European empires.

Is that what Bernie has in mind for our own era—a progressive internationalism, seen from a working-class standpoint that, in olden times, the social democrats would have heartily approved, with American power as its tool? No, that would be too much. In neither of his speeches has Bernie contemplated the uses of American power. Nor does he seem to have contemplated the sort of independent or nongovernmental foreign policy that, in times gone by, the social-democratic trade unions used to conduct.

Still, from one speech to the next, something in Bernie’s language does seem to be drifting in those directions, and the drift raises a possibility. In the 1940s, the moment had come for America to adopt a dramatically new foreign policy, and the political force that stepped in to propose a policy and promote it was the social-democratic wing of the American left—an aspect of American history that hardly anyone remembers. Why shouldn’t someone from the American left of our own time, a freethinker, propose a foreign policy for our own moment, as well? If somebody from the progressive wing of the Democratic Party wanted to break abruptly with the default-mode foreign-policy thinking of the modern left, if somebody wanted to revive a few of the instincts of the 1940s social-democratic left, updated and corrected for our own entirely different era, wouldn’t the door be open?

But I have allowed my thoughts to wander out of the zone of the realistic.

V.

In reality, there are many obstacles to any such development, and one of those obstacles is the pesky little question of an obsessive anti-Zionism in some pockets of the left. And Bernie Sanders’ career shows just how pesky the anti-Zionist obstacle can be.

Winston Churchill was known for his Zionist advocacy. But, in 1946, in his own speech at Fulton, he said nothing at all about the Jews and their national aspirations. And when Bernie Sanders stood at that same podium in 2017, he, too, said nothing, not one word, on those particular themes. This was strange, given that his purpose at Fulton was to break his own silence on foreign-policy themes. Nor did he do much to make up for the omission at Johns Hopkins, in his speech of last month. He devoted to Israel a single sentence, blaming Trump for encouraging the illiberal impulses of the Netanyahu government—which was a reasonable observation, but revealed nothing about his larger view. Only, how can this be? How can Bernie have said so little, when so many people have inquired into his opinion?

He alone could tell us. Still, I can guess at the developments that may have brought him to this point, beginning at the beginning. People from backgrounds like his in the Jewish immigrant working class tend to start out, on the simplest and most natural of grounds, as instinctive sympathizers with the Zionist project; and instinctive sympathy has been his own starting position. In one of his debates in 2016 with Hillary, he described himself as “somebody who is 100 percent pro-Israel, in the long run.” He relishes the memory of his student socialist idyll in 1963, toiling for the brotherhood of man as a guest of Hashomer Hatzair at the kibbutz Sha’ar Ha’amakim, near Haifa.

He appears to have paid not too much attention to Israel in the years that followed. And whenever he has glanced at it more recently, the spectacle has taken him aback. Every new violent incident between Israelis and Palestinians leads him to suppose that, given how the balance of power has tilted over the decades, the conflict must surely be, at bottom, a battle between Israeli cruelty and righteous Palestinian protest. He rebukes the Israelis. He recoils at the poverty in Gaza. He applauds any champion of the Palestinian cause who speaks a language of peace and reasonableness.

And then, having rebuked and recoiled and applauded, he repeatedly has the experience—or so I picture him—of stumbling across additional and complicating details, which lead him to wonder if he hasn’t been a little hasty in expressing a sympathy for this or that Palestinian protest. He condemned the Israelis for their repression of the Palestinian Great March of Return during the last several months, which seemed to him an act of excessive violence against a fundamentally nonviolent protest. Then he went on, after a while, to issue a second, solemn, newer, dismayed condemnation, this time of Israel and Hamas alike, the two of them together, as if he had lately begun to reflect on Hamas’ role in the protest and the violent implications.

Repeatedly he has welcomed onto his staff or into the inner circle of his political campaign people who share his sincere indignation at the plight of the Palestinians but who, after a while, turn out not to share his sympathy for the Israelis, too. Linda Sarsour cut a prominent figure in his 2016 campaign, and, then again, became prominent, as well, for her remark about nothing being creepier than Zionism. This cannot have pleased the old kibbutznik. The organization Our Revolution emerged from his 2016 campaign, and, earlier this year, Our Revolution endorsed the candidacy for governor of Ohio of Dennis Kucinich, who has aligned himself with Bashar al-Assad in the Syrian war. Bernie cannot have been happy about that, either. He declined to bestow his own, personal endorsement on Kucinich (who lost the primary). And yet he was stuck with the reality that, because Our Revolution is thought to represent his own movement, Bashar al-Assad’s name and his own were inevitably yoked together in press accounts of Ohio politics.

The authentic enemies of Israel in the American public do seem to notice the anti-Zionist buzz around him, and they are bound to wonder if, regardless of his Jewish roots, Bernie isn’t someone like themselves, a serious proponent of “From the river to the sea!” They hope he is. And continually he is obliged to explain that it is all a mistake, and Israel is not, in fact, creepy in his own eyes. The single most striking statement he has ever made on the Middle East came during a town hall meeting with his own constituents in Vermont in 2012, some of whom expected him to denounce Israel forcefully in regard to the Gaza War of that year. He observed, instead, that Israel had come under missile attack and did have to defend itself. He got a little heated in making the point, and when the constituents insisted on their denunciation, and went on insisting, he shouted, “Excuse me, shut up!”—which suggested that his sympathy for certain kinds of anti-Israel outrage has its limits.

Wouldn’t he be smart to straighten out these confusions? And wouldn’t a foreign-policy address be the place to do it, especially in a setting like Johns Hopkins last month, where no one was going to object to nuance and complication? I can only imagine that, whenever he thinks about doing anything of the sort, his politician’s instincts wave him away. The default position of the modern American left, as Walzer describes it, does not necessarily approve of being, as Bernie says, “100 percent pro-Israel, in the long run.” At Bernie’s rallies, the ebullient crowds are bound to contain a small number of single-issue social-justice warriors eager to wave their imaginary scimitars and chant, “From the river to the sea!” together with a far larger number of people who, in the face of a grisly chant, can be counted on to bite their tongues—which suggests that, among his public, there is a serious need for political education. Bernie loves to educate, as it happens. Didactic oratory is his greatest gift. He loves to educate, however, only on themes that are domestic, economic, and working-class, with occasional detours into global warming. And his public cheers the lectures. But that is because he sticks to his themes.

The man is in a fix. It is his own doing, too. He and nobody else is the leader who has ushered the marginalized and protest-oriented radical left with its many wacky university ideas into the American political mainstream; but, over the course of the 2016 campaign, he abstained from telling his admirers where they should stand on foreign policy. Even now, after he has begun to lay out a foreign policy for the left, he has offered no guidance at all on Israel-and-Palestine in particular, except by making a few staff appointments that open the sluice to the tide of anti-Zionism. And in comes the tide, filled with voices clamoring to erase Israel from the map.

Some of the anti-Zionists whom he has helped to define as admirably progressive are going to end up with a measure of national glamour, too. This may have already happened in Michigan with the election to Congress of Rashida Tlaib, who displays an inspiring vigor on behalf of workers’ rights but also turns out to be a champion of Israel’s demise. Tlaib is one more member of the newly BDS-ified Democratic Socialists of America. And, with a few more victories by otherwise appealing people like her, aren’t we going to discover that Europe’s crisis of the radical left has crossed the ocean?

I have fretted over this possibility in a previous essay—the possibility that, under an anti-Zionist pressure, the culture of the liberal left in America may begin to buckle and collapse, as has already happened in large parts of the socialist or social-democratic left in the United Kingdom and France and other places, too. It is the possibility that “From the river to the sea!,” which is a call for a pogrom, will begin to be heard in the Democratic Party itself, and Farrakhan will become an honored figure, and the spirit of anti-racism and tolerance and universal rights will undergo a few defeats. No one who contemplates the American scene has failed to see the possibility, though it may be that, in the Democratic Party, no one has wanted to recognize just how far these developments can go, or how quickly the developments can take place.

Something like that could happen, yes. It is imaginable. If it happened to the British Labour Party, why not to the Democrats?

VI.

And yet, and yet—when I tally up the left-wing similarities on one side of the Atlantic and the other, I keep stumbling on a difference. It is visible in the biographies of the top leaders. The British, French, and American leaders of the radical left of our moment, all of them, come from classic backgrounds in one corner or another of the pure and authentic left of the 1960s; but the corners are not identical. Jeremy Corbyn comes out of the radical Third Worldism of the British New Left in the 1960s, and Jean-Luc Mélenchon comes out of a sectarian French Trotskyism of those same years (namely, Pierre Lambert’s Internationalist Communist Organization, a moderately influential semiclandestine faction within the French Socialist Party, for a while). Each of those currents was Marxist. And both of those men have maintained a Marxist habit of systematic thought on anti-capitalist themes and world affairs.

Systematic thinking leads them to gaze with hostility upon the European Union and the Western alliance as a whole (because the Western alliance is the power structure of capitalism and imperialism). And systematic thinking leads them to gaze with a degree of sympathy upon Vladimir Putin (because, even if Putin’s right-wing style is not their own, his rejection of Western power represents an anti-capitalist resistance of sorts, therefore is to be applauded, and wasn’t the Ukrainian revolution of 2014 an anti-democratic putsch?—which is Mélenchon’s view especially). A decided proclivity for nonsensical fantasies about distant zones of the globe has dominated the Marxist imagination for the last 100 years, and the proclivity systematically induces Corbyn and Mélenchon, both of them, to cultivate a European fantasy of the exotic Third World—a romance of the nobly savage Arab resistance to the detested Zionist colonialists, in Corbyn’s case (though he also admires the Latin American Marxists), and a romance of the Latin American demagogues and dictators, in Mélenchon’s case.

Bernie Sanders went through his own phase of sectarian socialism at the University of Chicago in the early 1960s, which brought him into the ranks of the Young People’s Socialist League, or YPSL. This was the youth affiliate of the old Socialist Party, or what remained of it, in hyphenated merger with the grizzled trade union social democrats from the 1930s, the Social Democratic Federation. The combined organization, the SP-SDF, was not very large in the early 1960s, but neither was it insignificant. Its members counted for something in the leadership of the AFL-CIO. People from the SP-SDF were central to the civil rights movement in those years, beginning with A. Philip Randolph, no less, and his assistant, Bayard Rustin. And, in matters of world affairs, the SP-SDF was rigorously anti-fantasist.

Possibly Bernie wasn’t much of a YPSL. Some 20 years later, when he was mayor of Burlington, Vermont, he gave his municipal approval to the solidarity movement with the Sandinista National Liberation Front in Nicaragua, which some of the hardline anti-Communists in the SP-SDF of the 1960s would have advised him against—though some of the others would have approved, given that, in the beginning, the Sandinistas promised to be democrats. Sandinista solidarity appears to have been, in any case, strictly a minor episode in Bernie’s career. Mostly his foreign-policy thinking has conformed to the default mode that Walzer has described, with his new phase emerging only now, with its hint of something resembling a social-democratic internationalism. And all of this gives him a different quality than anything that can be seen in his European counterparts. In the European sympathizers with Putin there is a chilly spot for the Jews and the Jewish state—icy, in Corbyn’s case. But in the American enemy of oligarchical authoritarianism there is a warm spot.

The anti-Zionists and authoritarian fantasists among Bernie’s supporters find him endlessly frustrating for these reasons. You can read about Bernie’s shortcomings in Truthdig, where he turns out to be a major sellout, a non-socialist because a non-anti-imperialist, and a tool of the sinister Democratic Party. The anti-Zionists and the fantasists yearn for an American Corbyn. They want a national leader who will denote as realistic their own fictions and dreams about faraway dictators; and will usher the fictions and dreams into the American mainstream; and will say nice things about Hamas and bad things about Israel; and will offer an appalling speech to the Democratic National Convention; and will stand shoulder to shoulder with the outright bigots; and will drive everyone with a Jewish soul out of the left, except for a pitiful handful.

But America has produced no such leader. America has produced Bernie Sanders. America is different. Not different at every moment, but, even so, different.

Only, why is America different? I will return to this question next week.

***

This is the second of a three-part commentary on the American left. Read part one here.

Paul Berman is Tablet’s critic-at-large. He is the author of A Tale of Two Utopias, Terror and Liberalism, Power and the Idealists, and The Flight of the Intellectuals.