An Online Universe Without the Holocaust

Illustrated series ‘Radzyn’ reimagines shtetl life in a mysterious Polish town

I, like many who are the grandchildren of Holocaust survivors, grew up within my own personal Yad Vashem. I dreamt of concentration camps, my head forever full of stories of death and courage. But unlike the children of Holocaust survivors, the so-called second generation, who seem more viscerally linked to the trauma of the Holocaust, the third generation comes at it differently. To us, it can be approached more fluidly, with greater creativity, playfully even, if such a word can even be used in this context. To an outsider, such an approach may sound weirdly morbid, but how else is one to handle the strange tension that comes from living memories of a tragedy not one’s own?

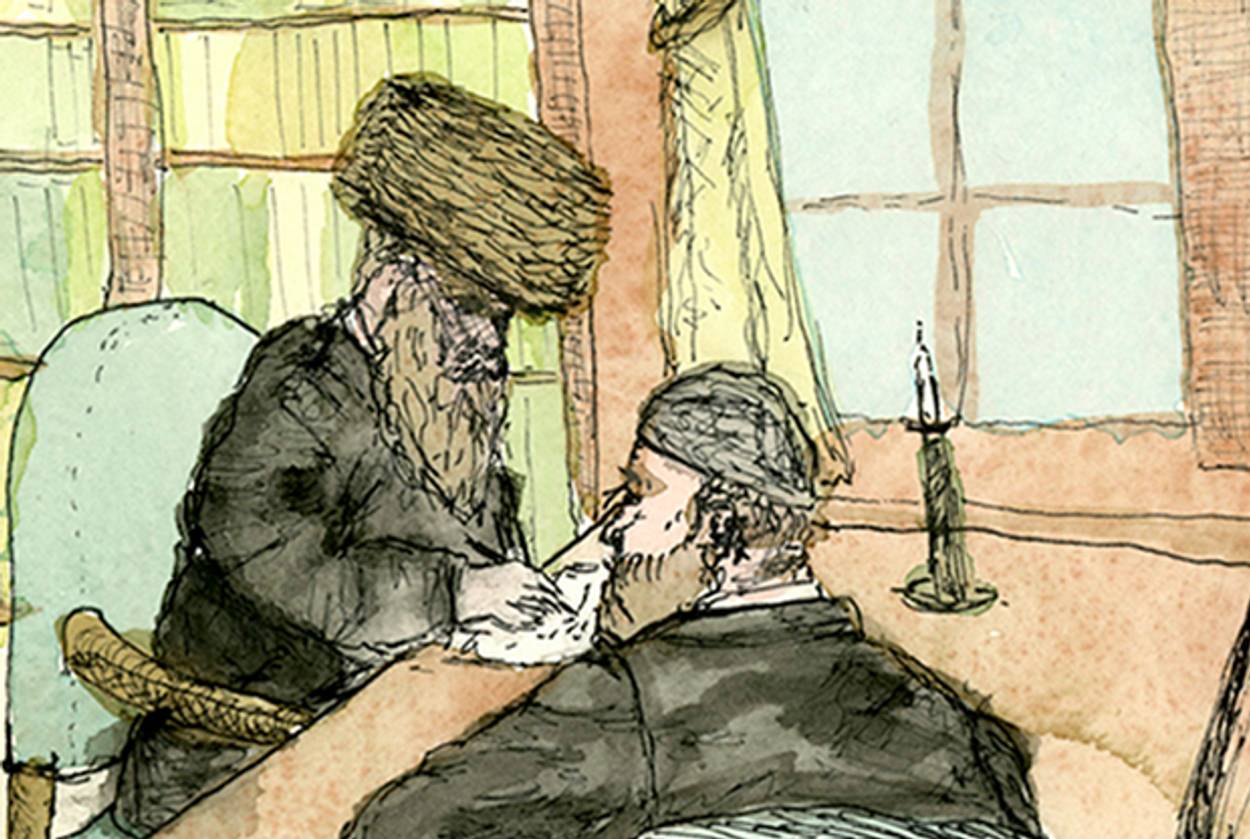

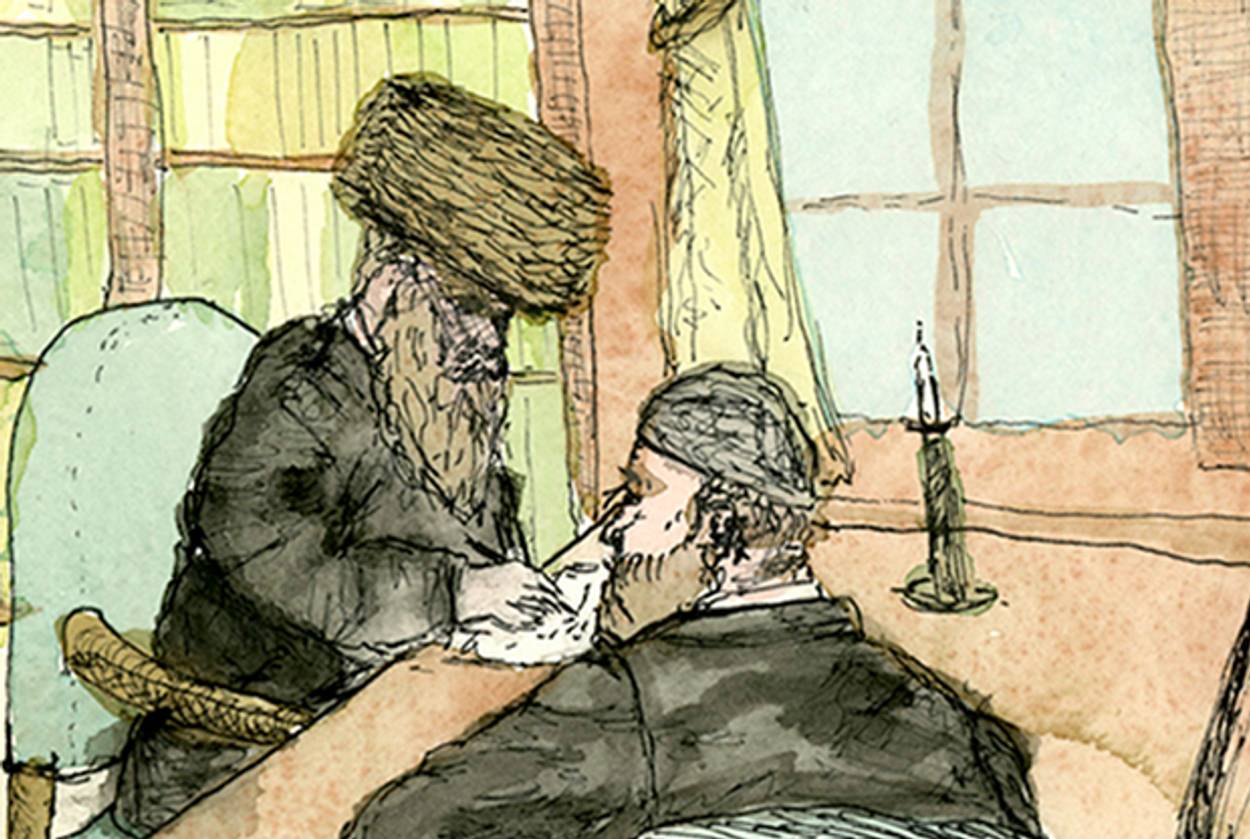

A wonderfully (perhaps blasphemously) imaginative answer to this question comes from the new illustrated online story series Radzyn by writer Michael Weber and illustrator Joel Golombeck. The story begins in 1933, as the Rebbe, the Holy Master of Radzyn, offers an ominous Sabbath day sermon. From there, the story moves back to 1889, where it explores the tensions and challenges of shtetl life. The central question of the story is this: What would a shtetl look like, if somehow, miraculously, it made it through the Holocaust wholly unscathed?

In that sense, the story dares to ask the question, what might Judaism have looked like had the Holocaust never happened? Or as Golombeck puts it, “We wanted to tell a story for the grandchildren and great grandchildren of survivors with a perspective defined by internal identity and character, as opposed to the one defined externally by Nazis…the driving force behind Radzyn is exploring the kinds of spiritual, national, and personal identities created outside the confines of being discriminated against.”

Told solely on the Internet, the story is a blend of midrashic and modern styles enlivened by Golombeck’s evocative images of shtetl life. As a whole, it signifies a step forward, not only for good Jewish art using new mediums to tell new stories, but also as an exploration into how the past persists and how we can create within this persistence. It is steeped in Hasidic tales, and yet it feels different enough to push the tradition forward. It helps wonder how we can integrate the Holocaust into a larger Jewish identity and not see it solely as a point of destruction.

That Weber and Golombeck choose to depict and tell the story solely through the Internet is not simply a convenient method of distribution, but an integral aspect of the storytelling. It not only immerses the reader in the story—and allows the reader to click on foreign words—but reinforces the fact that the project is not merely a re-capturing of a lost world, but the creation of a new one.

Joseph Winkler, a freelance writer living in New York, is a contributor to vol1brooklyn and The Rumpus.