Why ‘the Jews’?

Understanding history’s most viral meme

There are “the Jews,” and then there are the Jews, and they are mostly not the same. The Jews live next door or in the next village over. Some are helpful and friendly, others are aloof and greedy. “The Jews,” however, live nowhere in particular. They are a creature of cultural and psychological myth, living in people’s individual and collective minds. “The Jews” of myth also carry a stigma: They excel at communal action, secretive projects, and serve their own interests at the expense of others. At their most dangerous, “the Jews” are a successful conspiracy. When Jews are persecuted, it is usually because the persecutors are aiming at those “Jews” of conspiratorial myth, even as the blows fall on the heads of the local Jews, the ones without quotation marks.

This conspiratorial justification for the persecution of Jews is an important part of the larger, more familiar species of “Jew hatred.” Here is a useful anecdote. Matt Collins, a British neo-Nazi turned informer, described his former buddies in a 2019 New Yorker profile as sitting in a pub in Northern England aiming to “Get pissed, make threats, blame the Jews and go home.” Blame which Jews? It must have been the mythic ones, because in Warrington, England, Jews are thin on the ground; the Collins group might not have even known any real ones. They were ready for action, though.

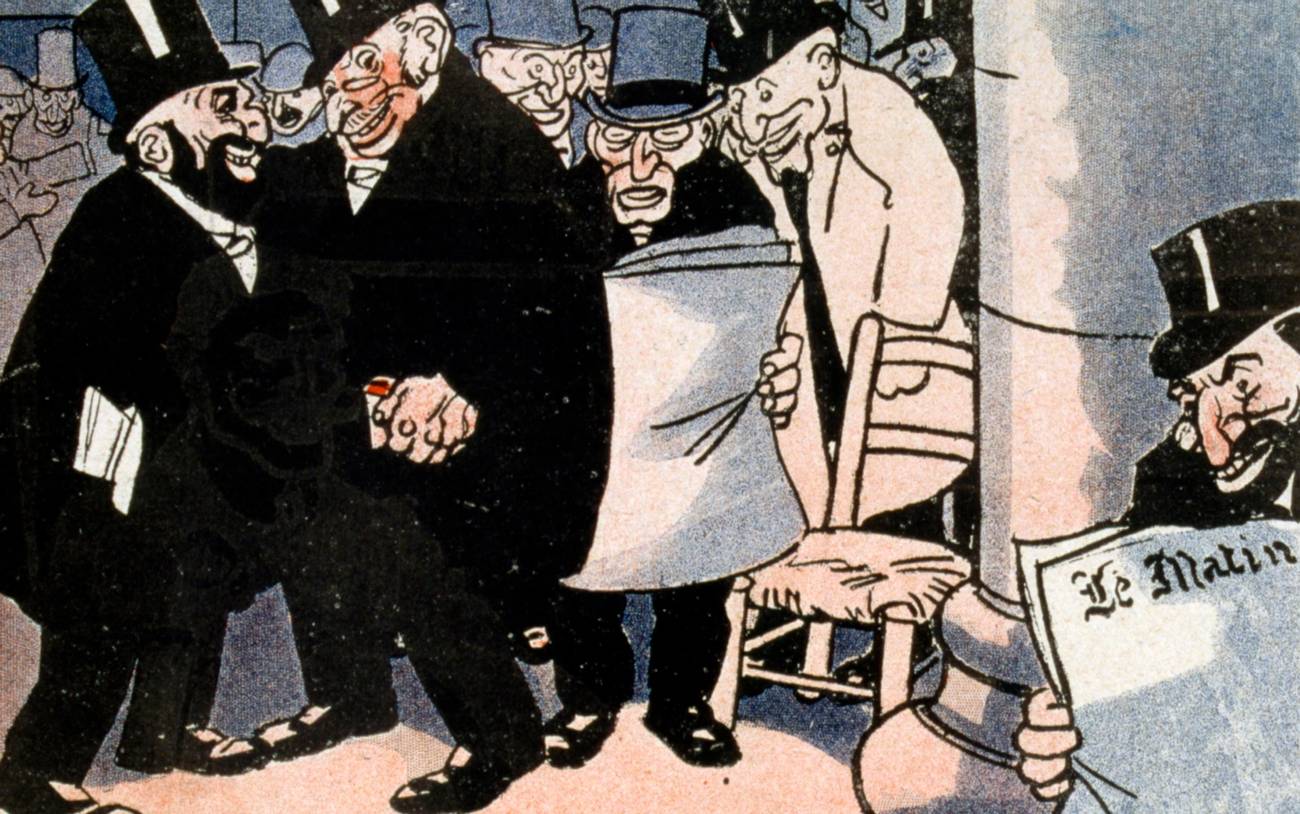

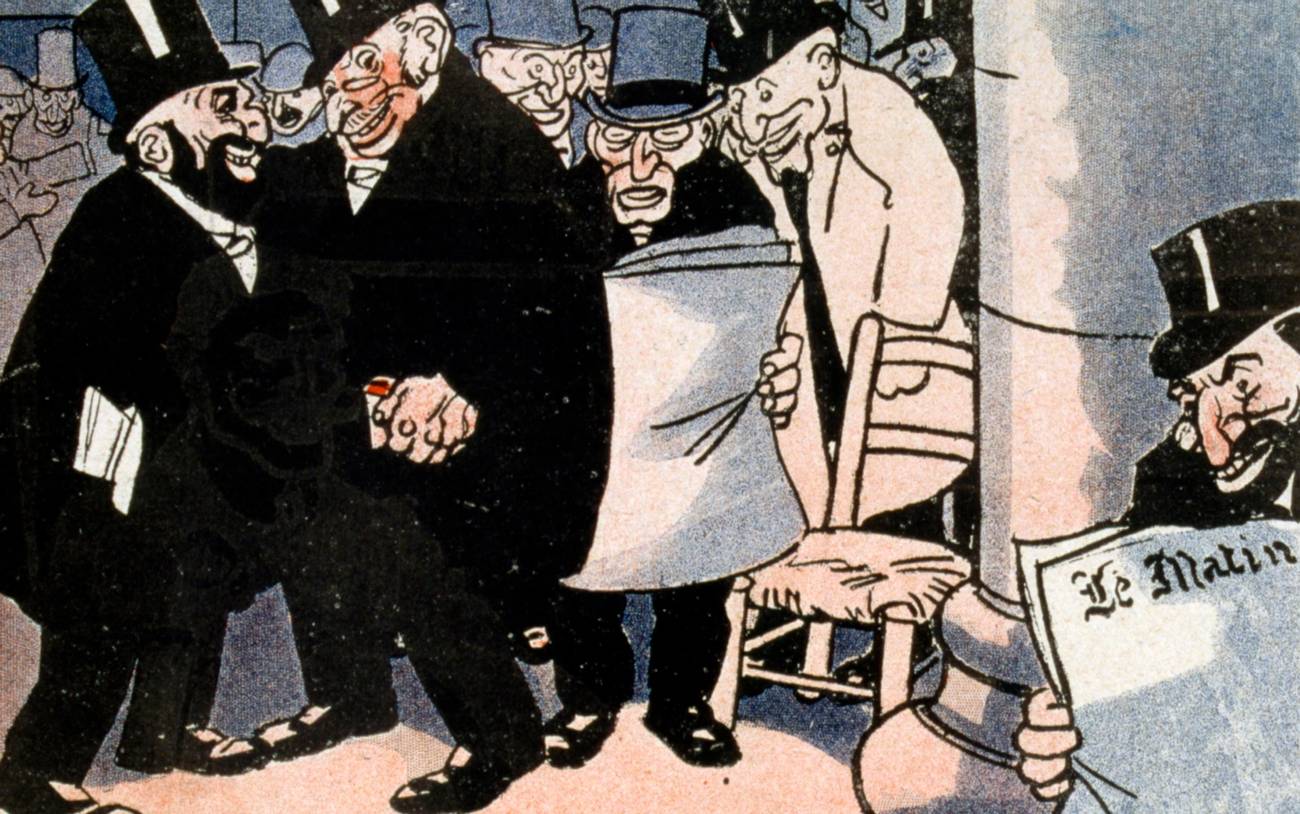

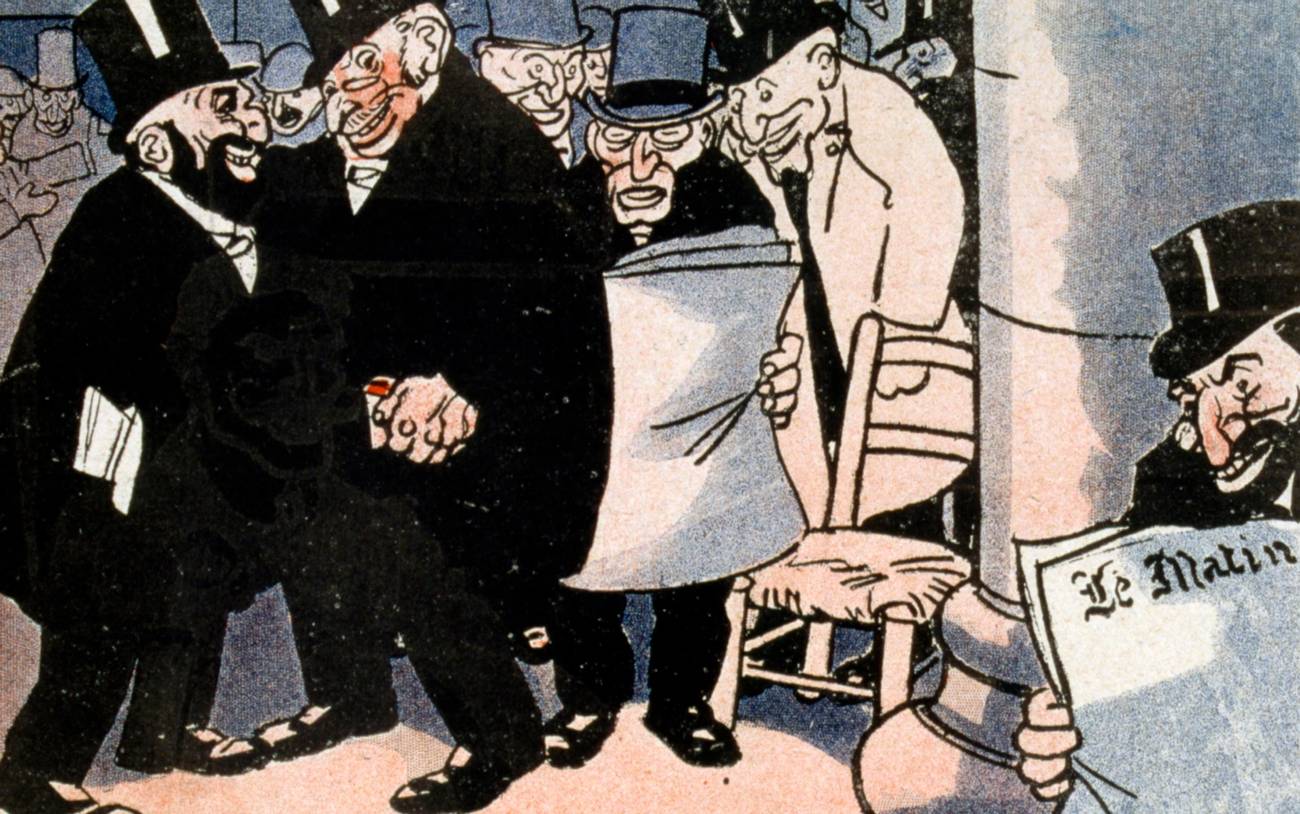

“The Jews” is also a meme, a bit of information that has the ability to spread like a virus among various populations, to become highly visible, and to serve as a target for a generalized mood of hostility and violence. The meme of “the Jews” is not encumbered by actual Jews, who are impeded by gravity, time, and traditional means of travel. Because it is a cultural phenomenon rather than a local reality, “the Jews” meme can leapfrog freely from one geographically disconnected but culturally networked community to another—from Christianity to Islam to communism—and hibernate for long periods.

It is an unusually adaptable meme, too, and finds a way to wiggle into every social, political, and cultural crevice. Its core message—that Jews have a unique capacity for collective agency—is the part that gives it such resilience across time and place. The varied, seemingly inconsistent charge sheet of offenses—from deicide and plague to racial pollution and financial manipulation—makes it adaptable in every temporal, social, or political context.

In its travels, the viral meme of “the Jews” has had lots of help. Person-to-person transmission is only one mechanism among many—and effective too, because it relies on human beings’ desire to carry and transmit the popular ideologies of their environment. Since the earliest days of the blood libel until the last decades of the 20th century, Christian doctrine was an effective carrier. Both left-wing and right-wing populism are ideal carriers, too, as are all varieties of demagoguery, and totalitarian movements like fascism and communism.

The broad reach of “the Jews”—alternately a myth, a meme, and a virus, with its powerful combination of ethnoreligious bigotry and conspiracy attribution—helps explain why Jews (no quotation marks) are disproportionately blamed when either a faith or secularism is considered to have gone astray. “The Jews” myth explains why, after so many centuries of evidently false and destructive accusations, something as new and specific as QAnon still immediately comes up with, of all things, charges of child trafficking against the Jews. While these misdirected attacks aim straight at “the Jews” of myth, they are of course absorbed by the real, local, proxy Jews. By understanding the nature of “the Jews” myth, it becomes a lot easier to answer the question, Why the Jews? Because with them, you are free to choose any accusation; as for the accused, any Jew will do.

In one respect, the conspiratorial persecution of Jews is welcome news: It suggests that what is abundant in the world is not a specific or personal hatred of Jews, but conspiracy-driven hatred in general, for which the Jews just happen to make a good target.

But the significant role of conspiracy in the persecution of Jews is not exactly good news: Regardless of how Jewish persecution begins, the results are often the same. Fear and hatred of “the Jews” may be even more resistant to countermeasures, and thus more resilient, than gut-level hatred of the actual Jews next door. With the latter, at least we can hold out hope for the positive impacts of education, familiarization, and facts. Conspiracy theories of any kind, however, are notoriously hard to combat. Facts and reasoning don’t get the job done, and proving a negative (“no, Virginia, there is no secret, invisible conspiracy”) is challenging.

Fighting antisemitism—that is, the conspiracy-driven kind of hatred—with communal organization or money or government power may make individual Jews and Jewish communities feel like they are “doing something.” There is some value to that; the feeling of agency or control can be enormously important to individual and communal health. But otherwise, it is often largely a waste of time.

A more effective counterstrategy to the viral meme of “the Jews” might target the carrier rather than the virus itself. As the linguist and evolutionary psychologist Steven Pinker has advocated, general enlightenment is the best antidote to a host of illiberal carrier ideologies, antisemitism and conspiracy theories among them. Conspiracy theories are dangerous for Jews no matter who the intended target is or how they start. Sooner or later, they all have a funny way of coming back to us.

The best way to fight antisemitism might be to just continue promoting liberal practices and thought. Achieving enlightenment rationalism on the scale of whole societies, alas, takes time and patience. It also runs against the grain of human nature, which is remarkably resistant to attempts by rationally minded people to stamp out its worst demons.

Eugene Bardach is Professor Emeritus of Public Policy at the University of California, Berkeley.