Are Educated People More Anti-Semitic?

A new survey shows that a remedy American Jews have put their faith in for the past century may now be spreading the disease

A foundational principle of the fight against hate in America is the belief that intolerance in general, and anti-Semitism in particular, are functions of ignorance that can be solved with education. We see evidence of this whenever concerns about intolerance or anti-Semitism become more salient. Proposed solutions frequently feature improved Holocaust education or expanded diversity, equity, and inclusion training. Profiles of anti-Semites tend to feature rural whites or urban minorities from low-educational backgrounds. Well-educated people tend to feel secure in their higher-class status and imagine that the dangers of intergroup hatred are concentrated elsewhere.

Indeed, widely cited studies of anti-Semitism support the conviction that it is associated with low levels of education. For example, the Anti-Defamation League’s Global 100 survey of anti-Semitism worldwide found that “among Christians and the non-observant, higher education levels lead to fewer anti-Semitic attitudes.” The survey, which included Iran and Turkey, found “the opposite is true among Muslim respondents …” Yet excluding school systems that may explicitly teach hatred toward Jews, education does appear to reduce anti-Semitism. After reviewing several studies, the sociologist Frederick Weil concluded that “the better educated are much less anti-Semitic than the worse educated in the U.S., and no other measure of social status (e.g., income, occupation) can account for this relationship.”

A large problem with this widely held belief—which has dominated the American Jewish community’s approach to combatting hatred since the days of Louis Brandeis—is that it depends on survey questions that probably fail to capture anti-Semitism among the well-educated. For the most part, these studies measure anti-Semitism simply by asking respondents how they feel about Jews, or by asking whether they agree with blatantly anti-Semitic stereotypes. But educated people, being experienced test takers, know these to be “wrong” answers.

For instance, a recent survey designed to gauge anti-Semitism on college campuses was based on respondents’ level of agreement with statements like “Jews have too much power in international financial markets” or “Jews don’t care what happens to anyone but their own kind.” Sophisticated respondents may be more likely to detect what they are being asked and give socially desirable answers that might fail to reveal a more nuanced degree of anti-Semitism. The belief that anti-Semitism is associated with lower levels of education may therefore be a function of who gets caught by surveys, rather than based on an accurate relationship between education and antipathy toward Jews.

We discovered that more-highly educated people in the United States tend to have greater antipathy toward Jews than less-educated people do.

To test this hypothesis, we developed a new survey measure based on what the human rights activist and former Soviet refusenik Natan Sharansky identifies as a defining feature of anti-Semitism: the double standard. We drafted two versions of the same question, one asking respondents to apply a principle to a Jewish example, and another to apply the same principle to a non-Jewish example. Subjects were randomly assigned to see one version or another so that no respondent would see both versions of the question. Since no one would see both versions of the question, sophisticated respondents would have no way of knowing that we were measuring their sentiment toward Jews, and no cue to game their answers.

When we administered these double-standard measures in a nationally representative survey of over 1,800 people, our results differed widely from the conventional view about the relationship between education and anti-Semitism. In fact, we found that more highly educated people were more likely to apply principles more harshly to Jewish examples. By preventing subjects from knowing that they were being asked about their feelings toward Jews, we discovered that more-highly educated people in the United States tend to have greater antipathy toward Jews than less-educated people do.

Contrary to previous claims, education appears to provide no protection against anti-Semitism, and may in fact serve to license it—in part by providing people with more sophisticated and socially acceptable ways to couch it.

Our survey consisted of 29 topics in which respondents were asked about a variety of political issues and controversies as well as demographic and background information. We oversampled K-12 teachers and higher education professors to provide additional statistical power to draw conclusions about people with higher education levels. Weights were used to ensure that the combined sample was representative of the United States. Embedded in the survey were seven pairs of items that asked respondents to apply a principle to either a Jewish or non-Jewish example.

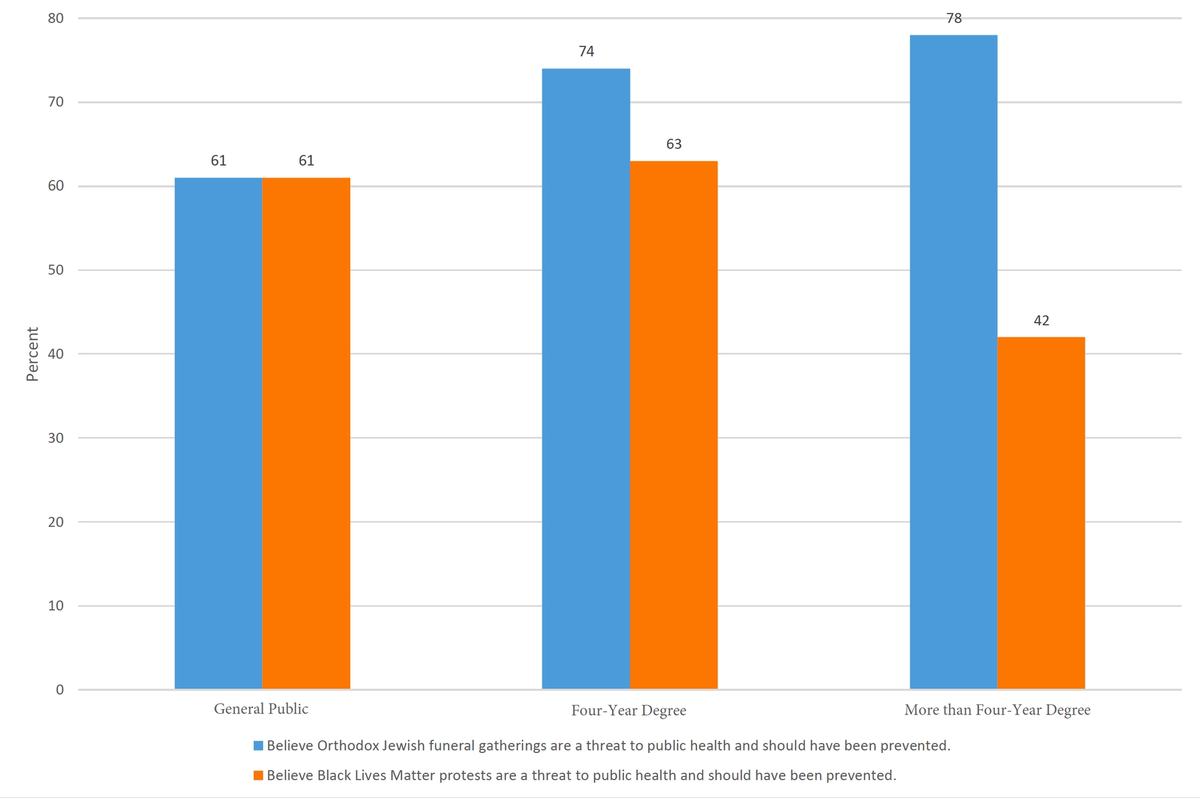

For reasons we explain below, we focused on four of the seven items to generate our measure of anti-Semitism. The first item asks whether “the government should set minimum requirements for what is taught in private schools,” with Orthodox Jewish or Montessori schools given as the illustrating example. The second item asks whether “a person’s attachment to another country creates a conflict of interest when advocating in support of certain U.S. foreign policy positions,” with Israel or Mexico offered as illustrating examples. The third item asks whether “the U.S. military should be allowed to forbid” the wearing of religious headgear as part of the uniform, with a Jewish yarmulke or Sikh turban offered as illustrating examples. And the fourth item asks whether public gatherings during the pandemic “posed a threat to public health and should have been prevented,” with Orthodox Jewish funerals or Black Lives Matter (BLM) protests offered as illustrating examples.

The logic of these double-standard items is that the situations are comparable enough in the Jewish and non-Jewish examples that respondents should answer them similarly on average. Some people may favor more or less regulation of what is taught in private schools, be more or less concerned about dual-loyalty issues, more or less deferential to military uniform rules, and believe that public gatherings posed more or less of a threat to public health. Regardless of how subjects feel about each of these substantive issues, they should not, in the aggregate, answer them differently if they are shown Jewish or non-Jewish examples.

For the remaining three items, the circumstances between the Jewish and non-Jewish items may have been different enough that a person could answer them differently without it reflecting antipathy or favoritism toward Jews. The first of these items asked whether Israel’s Basic Law is “discriminatory” when it says that “the state of Israel is the nation-state of the Jewish people.” The non-Jewish version of this item asked about the provision in the Danish constitution that says “The Evangelical Lutheran Church shall be the Established Church of Denmark, and, as such, it shall be supported by the State,” or the provision in the Jordanian constitution that says “Islam is the religion of the State and Arabic is its official language.” The second item asked about whether scholars from Israel or China should be subject to academic boycotts “to protest human rights violations by those countries’ governments.” And the third asked about whether professors should be fired for denying the Holocaust or for criticizing immigrants. For all three of these items, the situations might be considered dissimilar enough that the average respondent did not treat them similarly, and so we omitted them from our measure of anti-Semitism. Even so, the same patterns of results applied. Our measure of anti-Semitism for each of the two subgroups is the difference between how much the respective subgroups answered the Jewish and non-Jewish versions of each item.

We found that respondents with higher education levels are markedly more likely than those with lower education levels to apply a double standard unfavorable toward Jews. Across the four items in which the Jewish and non-Jewish versions of questions seemed the most similar, and which the overall sample answered roughly in the same way, subjects with college degrees were 5 percentage points more likely to apply a principle harshly to Jews than to non-Jews. Among those with advanced degrees, subjects were 15 percentage points more unfavorable toward Jewish than non-Jewish examples.

Looking at these four items separately, we observe respondents with higher education levels answer more unfavorably toward Jews for three questions and no difference for one. On the question of regulating the content of private schools, people with higher education levels favor more government regulation, but do not appear to apply that principle very differently if the illustrating example is an Orthodox Jewish or Montessori school.

When asked whether “attachment to another country creates a conflict of interest,” respondents with a four-year degree and those with advanced degrees were respectively 7 and 13 percentage points more likely to express this concern when the attachment in question was to Israel rather than Mexico. People with advanced degrees were 12 percentage points more likely to support the military in prohibiting a Jewish yarmulke than in prohibiting a Sikh turban as part of the uniform. Those with four-year college degrees answer this question the same whether the example is Jewish or Sikh.

The overall sample was fairly concerned about public gatherings during the pandemic, with 61% supporting the prohibition of public gatherings, whether for an Orthodox Jewish funeral or for BLM protests. Those with a four-year degree were 11 percentage points more likely to oppose these public gatherings for Jewish funerals than for BLM protests. People with advanced degrees were 36 percentage points more likely to want Orthodox Jewish funerals prohibited than BLM protests.

Our double-standard measure of anti-Semitism does not allow us to gauge the absolute level of anti-Semitism in the United States, since we focus on items where the average person finds the Jewish and non-Jewish version of items to be comparable. By design, the average person’s result will be close to zero. But this approach does allow us to break out the sample by education level to see where there is relatively more or less antipathy toward Jews. Contrary to conventional wisdom and past research, people with more education appear more unfavorable to Jews.

This greater antagonism toward Jews among the more educated is troubling for a number of reasons. First, Jews may be mistaken about where threats to their interests predominate. Jews may believe that dangers mostly come from distant and unfamiliar groups rather than from circles in which they tend to live. Second, well-educated people tend to have greater influence over the course of events, so it does not bode well for Jews to be disfavored by them. Third, our strategies for addressing intolerance in general, and anti-Semitism in particular, tend to revolve around the belief that group-hatred is caused by ignorance, and that the solution is more education. Yet if more-highly educated people are more hostile with respect to Jews, higher educational levels and more courses and training could increase prejudice, rather than diminish it.

At the very least, it seems that an education that simply provides information about historical events, civil liberties, and other cultural groups is insufficient. Addressing anti-Semitism and prejudice more generally may require the cultivation of virtue. Specifically, it requires the formation of a kind of character that is not only familiar with other outgroups and democratic norms, but also has the integrity to behave in ways that demonstrate consideration of their interests and restraint in the use of political power in the pursuit of personal interests.

As Harvard professor and Yiddish scholar Ruth Wisse has argued, anti-Semitism has not thrived because of ignorance, but because it “forms part of a political movement and serves a political purpose.” Those political causes making use of anti-Semitism are increasingly favored by the well-educated in this country. Countering the anti-Semitism of the well-educated will be a political and moral struggle, not one that can be addressed by conventional approaches and conceptions of education.

Jay P. Greene is a senior fellow at Do No Harm and a senior research fellow in the Center for Education Policy at the Heritage Foundation.

Albert Cheng is an Assistant Professor of Education Policy in the Department of Education Reform at the University of Arkansas.

Ian Kingsbury is Director of Research at Do No Harm, a health care advocacy group.