At Sotheby’s, One Last Glimpse Of Jewish Treasures

There was plenty to be found at Sotheby’s “Important Judaica” auction, including the world’s oldest complete Ashkenazi siddur (price: $300,000)

Considering it’s a place where the world’s richest people gather to purchase the world’s most expensive things, Sotheby’s has a surprising populist streak. You or I or anyone can take the Second Avenue Subway to 72nd street, walk right into the auction house’s Yorkville high-rise—a glass-and-steel cube with feel of an art museum with an investment bank hidden somewhere in back—and catch one final glimpse of the world’s treasures before they vanish into the hallways, yachts, private train cars and safe-deposit boxes of the well-heeled. As a possible prospective buyer, you can even touch the treasures, or, at minimum, make someone else touch them: A couple weeks ago, at a public display of the lots on sale at a December 20th auction of Important Judaica, I watched in mild amazement as a curator opened a 14th-century illuminated Tanach to show off the trellises of micrography looping across its opening pages. Its projected sale price was somewhere between three and five million dollars, and at the auction on December 20th it was in its own case in the front of the hall, front-lit so that its pages emitted a heavenly and expensive glow. A Sotheby’s auction is a forum of pure exchange, where the prices are so astronomical, and spent with such astounding speed, that they stop corresponding to any conceivable earthly value. The difference between a $15,000 pair of 18th-century Torah finials and a $20,000 pair of 18th-century Torah finials, sold within minutes of each other, is hopelessly abstract, although obviously the difference is also pretty concrete, namely $5,000. Paying a quarter-million bucks for a single book, even a very beautiful or rare one, is an absurdity when you really get down to it, and yet at a Sotheby’s auction the coffee, and the drama, both come free of charge.

On December 20th, a small museum’s worth of Judaica changed hands. A copy of the original newspaper emblazoned with Emile Zola’s J’Accuse!, described in official materials as “the most famous front page in journalism history,” went for around $8,000. A 16th-century Tunisian yad fetched $12,000, although one assumes its pointing days ended a long time ago. The collection told strange and wonderful Jewish stories: There were Renaissance-era letters from Christian scholars written in perfect Hebrew, a 17th-century schita manual with bovine organs illustrated in varying shades of red, an early copy of Herzl’s Altneuland. My favorite: A wall-sized 17th century Dutch map of Eretz Yisrael, the cartographic dream-world of someone who had obviously never been to the place, with Biblical armies marching between endearingly mislocated cities, mountain ranges, forests, and deserts. The objects on offer were precious fragments of a vast and inexplicable history, each one a tiny universe of meaning—for $32,500, someone walked away with the only existing full run of Israel’s Messenger, the English-langauge newspaper of the Jewish community of early-to-mid 20th century Shanghai. As if by some hidden kabbalistic instrument, these fragments of light were being scattered to unknown corners of the cosmos—after all, most of the buyers, and all of the sellers, weren’t even in the room.

Still, enough collectors were there to keep things interesting for the interlopers. A bidding war erupted over a 20-odd thousand-dollar kiddush cup of some kind. A lightly bearded man in a black ascot leaning against the back wall spent $27,500 on a 19th-century hand-sewn Bavarian Torah mantle, edging out a smartly-suited fellow in a velvet kippah seated a few rows in front of me. The man in the suit would pace and stroke his chin, stoically raising an index finger when he wanted to up the bidding. I imagined suit guy and hat guy were rivals, until they spent most of the second half of the auction consorting in a far corner of the room. There were a pair of frock-coated Litvaks—“I bought a menorah,” one deflected when I asked what had brought him to the auction—elite-level college librarians (Mazal tov, Quakers: It was a big day for the University of Pennsylvania’s Judaica collection), and an older gentleman in a bolo tie, a self-described reform Jew with a seemingly bottomless appetite for Jewish ritual objects. Although he came away with enough loot to seed a small shul, after the auction bolo man talked the most about the one that slipped away: An exquisite centuries-old miniature torah with a silver crown and shield, which landed just out of his price range. Furtive whispers in French, Yiddish, and Hebrew would sometimes burble throughout the seventh-floor hall, which was lined with proxy buyers manning elevated phone banks, the representatives of people speaking unknowable languages from unknowable places. The hall had the order and solemnity of a courtroom, along with the excess and wild possibility of a casino.

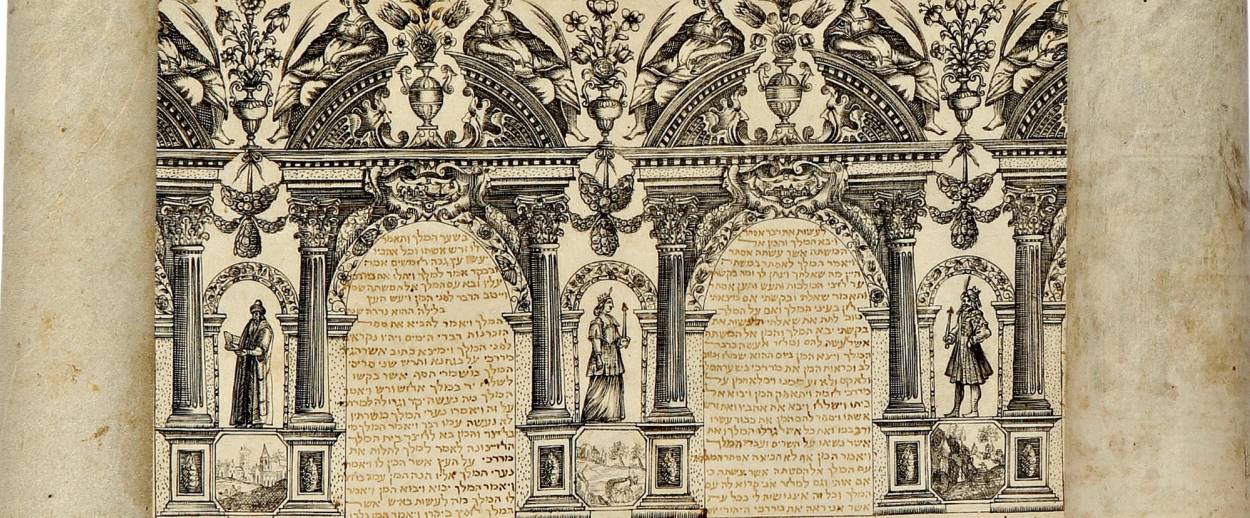

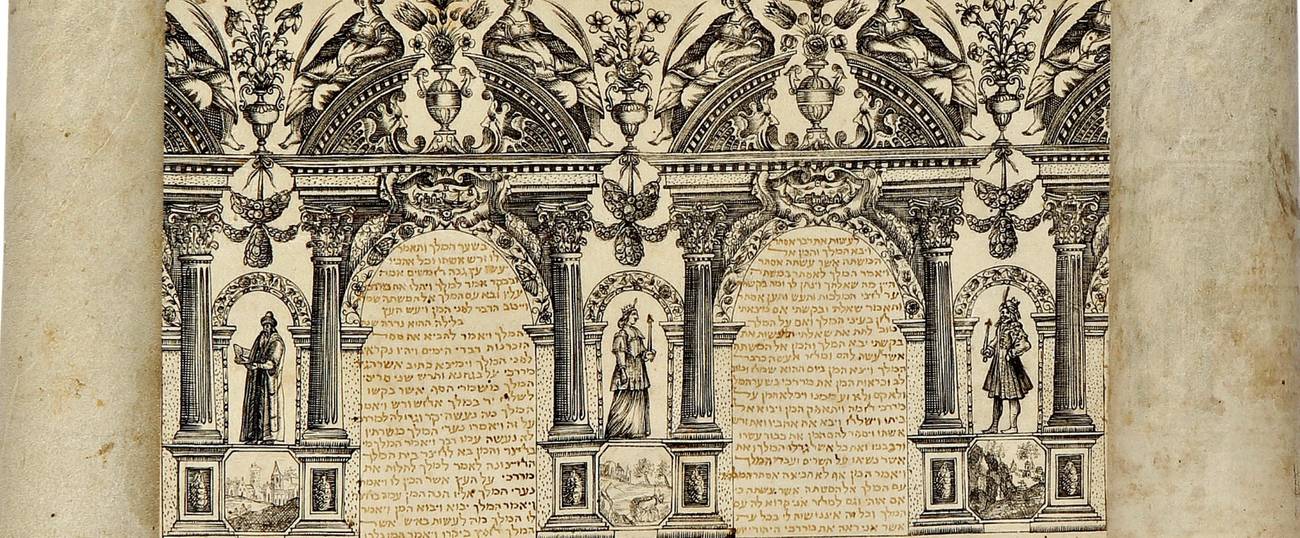

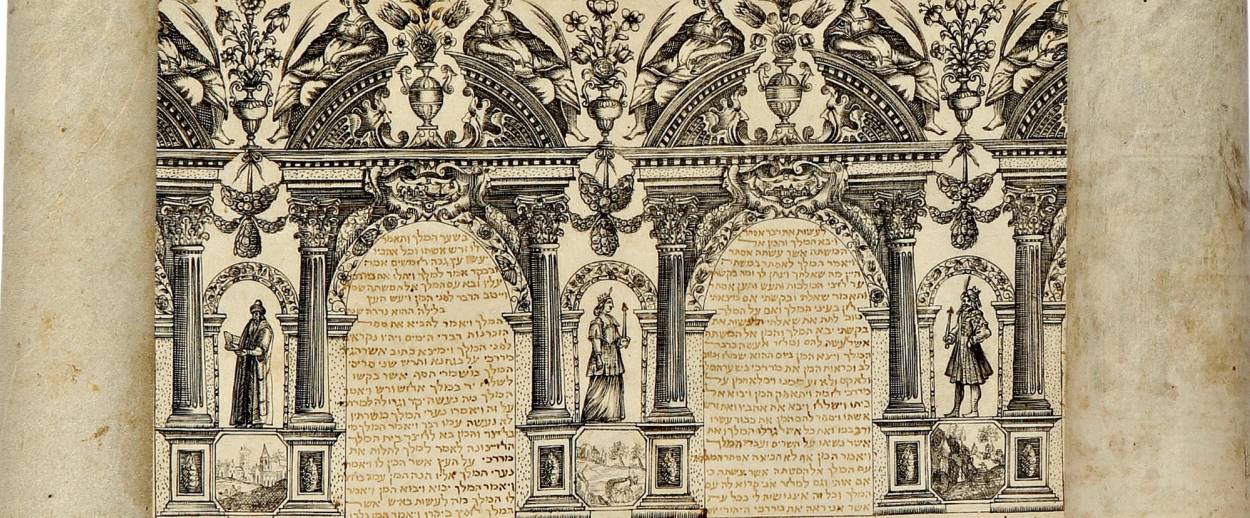

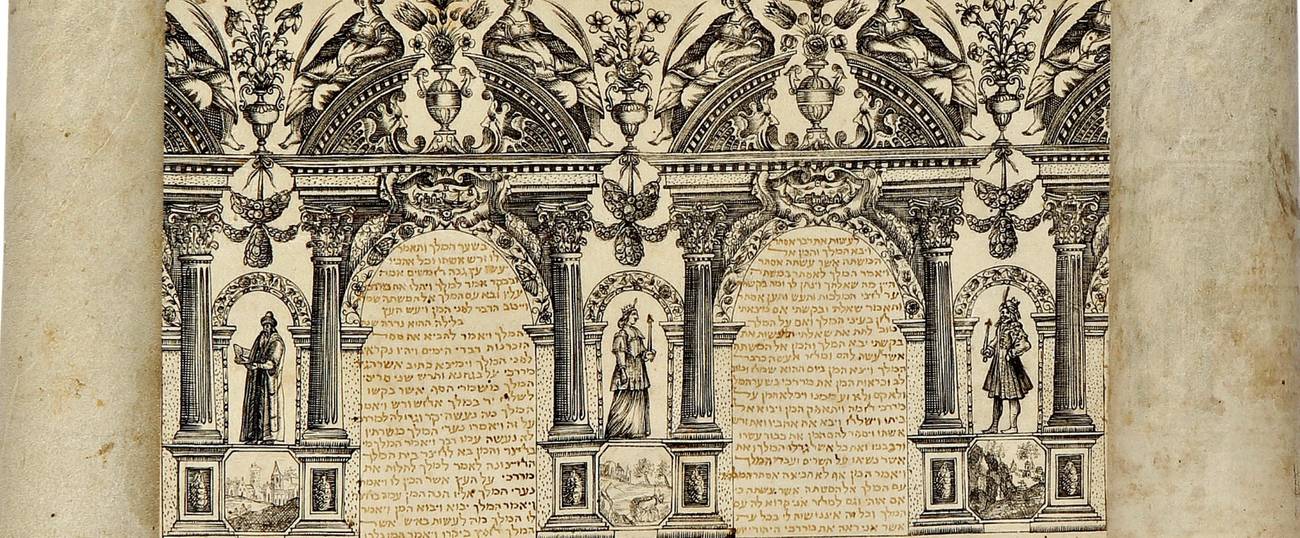

Auctions, like a blackjack table, proceed with ruthless efficiency. Every once in awhile, the auctioneer would deign to give a perfunctory and even slightly clinical description of what was being sold: Megillahs were “Esther scrolls,” menorahs were “Hanukkah lamps.” The auctioneer stood behind a podium positioned directly under lot 9, an ecstatic 1895 Jean-Leon Gerome painting of Mount Sinai where the ethereal horns blast from Moshe’s forehead like strobe lights at a rave, a set-up which ensconced a scene of searing spiritual intensity within the most secular proceedings imaginable. The auctioneers spoke just slowly enough to give bidders a moment to think about how much they’d really like to spend, but also quickly enough to create a sense of urgency, thus inducing them to spend even more. The tempo at a high-end auction is relentless: treasuries vanish in the space of minutes; libraries evaporate into cash. An auctioneer seldom goes off-script. They recite numbers—which, again, feel utterly meaningless—scan the hall, give fair warning, and then gavel objects into the ether. There’s no banter, no warming up the crowd for the showcase lots. Only subtleties in an auctioneer’s tone hint that something especially important is happening. During the sale of a spectacular 17th-century Dutch illustrated megillah, the auctioneer repeated the climbing going rate in a reverent whisper—an appropriate tribute to the item on offer, in which the Purim story unfolds within latticeworks of classical columns and arches, and Esther, Haman and Mordechai eye one another across courtyards of Hebrew text. (It didn’t hit its pre-auction guarantee, and therefore didn’t sell. If you are a museum, please consider buying it).

Morning turned into afternoon. For a shade over $300,000, off went the oldest known complete Ashkenazi siddur on earth, an early 16th-century marvel hidden away in a French monastery library for nearly its entire existence. The book went unused for centuries, and at the public exhibition I saw text blacker than the vacuum of space, screaming from pages that light had barely ever touched. Within the span of 15 minutes, a man on a cell phone spent about $700,000 bidding up a pair of medieval illuminated manuscripts, besting the ever-pacing suit guy for the more expensive of them. Later, there was informed speculation as to who the person on the other end of the line was, although it wasn’t a name that someone outside of the world of competitive high-end Judaica collecting would necessarily have recognized. Perhaps the mystery buyer was disappointed when lot 191 was withdrawn—at the close of the auction, it was announced that the Metropolitan Museum had purchased the 14th-century Tanach for an undisclosed amount.

“It’s not so good, the situation in the market,” a wiry Israeli man in a casual buttoned-up shirt told me as the crowd dispersed. He was an art dealer, and got to see how the next-lowest tier in the high-end Judica market operated on a day-to-day basis. “An auction doesn’t show what’s happening during the week,” he explained, before offering a sweeping socio-historical and perhaps even metaphysical theory on why the market had softened. “There’s no new generation of young people with Jewish soul, and it’s a problem. Rich people buy contemporary art. It’s hard to explain to them the rarity of a 17th-century menorah.” The anxieties that haunt seemingly every corner of Jewish existence apparently penetrated even this tiny and rarified precinct—add Sotheby’s to the long list of unexpected reminders that the Jewish soul is constantly threatening wild swings in direction.

Or maybe it isn’t really. As the crowd dispersed, handlers wheeled away the 14th-century Tanach, the first leg of a journey that will eventually end at the Cloisters sometime in 2018. Meanwhile, a small group of men, suit guy and phone guy, Litvaks and Jewish magazine contributors, faced east to daven mincha.

Armin Rosen is a staff writer for Tablet Magazine.