Auction: Taft’s Anti-Semitic Letter Opposing Louis Brandeis’s SCOTUS Nomination

Bidding begins at $15,000, if you’re into that sort of thing

If you’re into collecting anti-Semitic relics, do I have a piece of history for you. That is, if you can afford it.

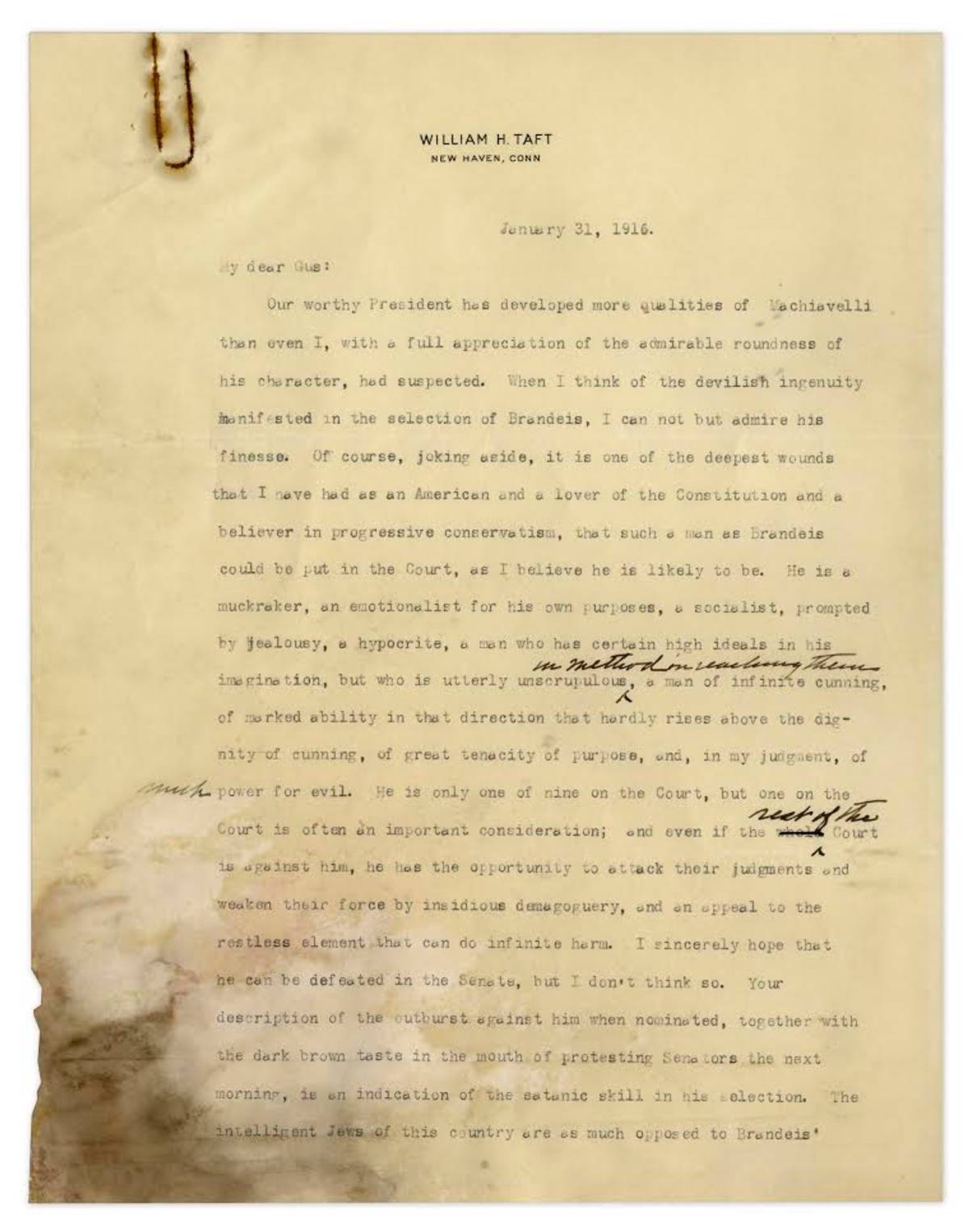

On Thursday, beginning with a minimum bid of $15,000, you can participate in an online auction for a chance to own a relatively anti-Semitic letter written by ex-President William Howard Taft to Washington-based Jewish journalist Gus J. Karger, in opposition to Louis Brandeis’s Supreme Court nomination by then-President Woodrow Wilson. Brandeis, of course, is the first Jew to have served on the Supreme Court, from 1916-1939.

Taft’s letter is dated January 31, 1916, just two days after Brandeis’s nomination. It should be noted that Taft, in a 1920 address, said that “anti-Semitism is a noxious weed that should be cut out. It has no place in free America.”

Well then, here are some of its low-lights of his letter, written just four years prior:

— “[Brandeis] is a muckraker, an emotionalist for his own purposes, a socialist, prompted by jealousy, a man who has certain ideals in his imagination, but who is utterly unscrupulous (illegible handwriting here), a man of infinite cunning, of marked ability in that direction that hardly rises above the dignity of cunning, of great tenacity of purpose, and, in my judgment, of much power for evil.”

— Taft described Brandeis’s nomination as has having come in some way by virtue of “satanic skill.”

— “The intelligent Jews in this country are as much opposed to Brandeis’ (sic) nomination as I am, but there are politics in the Jewish community, which with their clannishness embarrass leading and liberal and clear-sighted Jews.”

— “…Brandeis has adopted Zionism, favors the New Jerusalem, and has metaphorically been circumcised (sic). He has gone all over the country making speeches, arousing the Jewish spirit, even wearing a hat in the Synagogue while making a speech in order to attract those rabbis… If it were necessary, I’m sure he would have grown a beard to convince them that he was a Jew of Jews.”

In his review of Melvin Urofsky’s biography of Brandeis, Tablet columnist Adam Kirsch traced Brandeis’s political and idealistic paths, from growing up with parents who, as Kirsch writes, “were not so narrow as to allow their religious beliefs to overshadow their interest in the broader aspects of humanity,” to attending Harvard Law School, to becoming head of the American Zionist movement, from 1914-1921.

His major achievement, Urofsky convincingly argues, was to make Zionism acceptable to newly Americanized Jews, by showing that Zionism and American patriotism did not conflict. On the contrary, he always insisted that “the highest Jewish ideals are essentially American,” that “to be good Americans, we must be better Jews, and to be better Jews, we must become Zionists.” One reason Brandeis was so enthusiastic about Palestine, especially after he visited in 1919, was that he saw in it a blank slate for Jews to create the kind of democratic, egalitarian society he was working for in America.

It followed that American Jews did not have to make aliyah to be genuine Zionists. Rather, Brandeis laid out the terms of the compact that still governs American Jews’ relations with Israel: they would offer money and moral support, but not sacrifice their Americanness. When Brandeis was nominated to the Supreme Court, he took it as vindication: “in the opinion of the President,” he wrote, “there is no conflict between Zionism and loyalty to America.” This is what almost all American Jews still believe, despite increasingly vocal criticism of Israel and “the Israel lobby.” For this, as for so much else, Urofsky reminds us, we have Louis Brandeis to thank.

Brandeis was confirmed to the Supreme Court on June 1, 1916. Oh, and Taft joined him in 1921 until 1930, when he died.

Jonathan Zalman is a writer and teacher based in Brooklyn.