BDS: Russia vs. Israel

The two cases have little in common, other than a general lack of seriousness about U.S. foreign policy

Russia’s slow and grinding invasion of Ukraine has united much of the West in moral opposition that crosses party and national lines. It has resulted, moreover, in many Western governments imposing significant sanctions on Russia, including removing it from the SWIFT payment processing network and freezing its currency reserves. Even more remarkably, a wide range of private actors have joined in, going above and beyond what the law requires. Many Western businesses have closed their Russian operations or cut off services in the country. The Metropolitan Opera, FIFA, Wimbledon, and numerous film festivals have banned Russian artists and athletes, though some make exceptions for those who will take the personal risk of publicly denouncing their country’s government.

The imposition of sanctions on Russia, and the shunning of it by Western firms and cultural institutions, has whet the appetite of opponents of Israel. Those who have championed the Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions (BDS) movement against the Jewish state—a fabulously unsuccessful cause to date—see in Russia a kind of precedent, or at least a playbook for cutting Israel out of the Western economic and political order. Conversely, the sanctions against Russia have caused confusion for many supporters of Israel, who in recent decades have sought to portray broad-based economic sanctions and cultural and institutional boycotts as means of imposing discriminatory double standards, rather than expressions of political righteousness. So what exactly is the difference between BDS Russia and BDS Israel—other than the small matter that Russia, unlike Israel, has engaged in repeated acts of gross territorial aggression against neighbors that never attacked it?

To start, the Western sanctions regime against Russia does not, in fact, demonstrate some moral or legal measure in international affairs. Russian military operations in Chechnya, Georgia, Crimea, eastern Ukraine, and Syria between 2000 and 2015, for example, elicited no such response. When Vladimir Putin invaded Georgia in 2008 and conquered a fifth of the country, the international community barely shrugged; indeed, some criticized Tbilisi for its stubborn insistence on restoring the country’s pre-invasion borders. Just a few years later, when Russia hosted the Winter Olympics, it housed workers in Olympic village barracks built in the newly occupied territory; there were no cries of “illegal settlement construction.”

A few days after the final Olympic event, Putin invaded Ukraine, annexing Crimea and installing puppet governments in eastern Ukrainian regions. This time, the European Union and United States did respond with narrow sanctions on certain Russian businesses and individuals, but the effect was minimal. Western companies, including American ones, continued to be deeply involved in the Russian economy. Moscow remained in good standing in most international organizations, and was welcomed by the United States, Germany, France, and the U.K. as the linchpin in negotiations over Iran’s nuclear program. In perhaps the clearest indication of Western acceptance of Russian aggression, it continues to this day to sit alongside the United States, United Nations, and European Union as one of the members of the “Middle East Quartet,” a diplomatic effort designed to create a Palestinian state in the West Bank and Gaza—akin to appointing Bernie Madoff to the board of the Federal Reserve. Indeed, only a few weeks before Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February, President Joe Biden made clear that the United States would not hold Russia accountable if it confined itself to a “minor incursion” against its neighbor.

The current sanctions regime, then, is more a function of the timing and aesthetics of Russia’s most recent war than it is of any firm Western stance on the immorality or illegality of invading a sovereign state. Rather than continue shaving off pieces of its neighbors here and there, this time Moscow openly sought total conquest, backed by genocidal language about how the Ukrainian people themselves don’t or shouldn’t exist. When the Russian armies failed to achieve these goals quickly and demonstrated a shocking lack of competence, a traditional ground war ensued, complete with indirect fire, aerial bombardment, infantry maneuvers, shelling, and evacuations, all fought in full public view. The unexpectedly large gap between Russia’s war aims and its military performance created a space for the United States and the European Union to hit back with a sanctions regime that would have been unimaginable if Ukrainian forces and cities had fallen as quickly as Russian (and U.S.) intelligence had predicted they would.

It is common for individual countries to impose economic restrictions on hostile states, such as the U.S. embargo against Cuba, the longest trade embargo in modern history. But such national sanctions regimes typically stand alone, and are thus much less effective. One of the original ideas behind the United Nations Security Council was that it would have the power to authorize, and indeed require, collective sanctions by all U.N. members as a measure short of war to punish breaches of international peace.

Given the council’s well-known and congenital dysfunction, U.N.-imposed sanctions are quite rare, limited to rogue states like Libya and North Korea and focused narrowly on key industries like weapons manufacturing. Because sanctions also carry a significant cost for the countries implementing them, there has been a growing trend in recent years to make Western-imposed sanctions quite specific, singling out particular firms and individuals. The phrase “targeted sanctions” carries a connotation of efficiency and lethality, like “targeted strikes.” But in practice, the purpose of “targeted sanctions” is to provide the optics and political benefits of “doing something” at relatively low cost.

Even the word “sanctions” says little about the justice or legality of the relevant measures. The Arab League boycott of Israel, for example, was a collective sanctions regime designed to destroy the Jewish state. On the other hand, the famous international sanctions against South Arica in the 1980s were designed to end the practice of apartheid. One cause was hateful, and the other righteous; but as far as the economic sanctions themselves went, the only difference between them was the eventual outcome. (It is even disputed how much of a role sanctions actually played in ending apartheid; another plausible explanation is the collapse of the Soviet Union.)

Economic sanctions are merely a tool, like bullets—a continuation of politics with other means, always linked to the strategic goals of the countries imposing them. Sanctions themselves are morally neutral—it all depends on the circumstances in which they are imposed. It is not “hypocritical” or “inconsistent” for the United States to support sanctions on Russia while opposing them against Israel, any more than it is to support sanctions against Venezuela while opposing them against Mexico.

There has never been any U.S. popular majority for BDS against Israel, which is why the movement has been so shambolic.

Cultural boycotts are a different matter. Economic sanctions are imposed by the state, and have been a tool of warfare and diplomacy for centuries; in the United States, they require significant actions by Congress and the White House to ban or restrict trade, meaning they derive their legitimacy from the consent of voters, and depend on the continuation of democratic support. Sometimes there is enough public pressure driven by democratic majorities to also include certain kinds of cultural boycotts, as in the case of South Africa. But there has never been any such U.S. popular majority for BDS against Israel, which is why the movement has been so shambolic.

The case of Russia is more complicated. It is unclear at this point how much of U.S. policy is being driven by bottom-up public outrage, and how much by top-down U.S. geopolitical strategy. That lack of clarity has resulted in a sanctions regime that does not seem to be deterring Russian military action or changing the minds of decision-makers in Moscow, but which does appear to be deliberately penalizing private Russian citizens. It’s not surprising that Western companies serving Russian customers have decided to leave Russia, given the sanctions climate and general economic turmoil. Some are motivated, no doubt, by pandering to what they perceive as the prevailing public mood, with echoes of “freedom fries” and “liberty cabbage.” But it’s not clear what is being achieved by intentionally harming private Russian entities and individuals, or by banning the participation of Russian artists and athletes in cultural events abroad.

Some have justified these penalties as a means to encourage ordinary Russians to overthrow Putin or force him to stop the war—actions that would of course be either futile or suicidal for people who have no choice but to live at the mercy of the Russian security services. Sanctions and boycotts designed to magnify civilian suffering also go against the international humanitarian goal of limiting the spillover effects from conflicts between armies.

What’s more, sanctions and boycotts untethered to any specific strategy or policy outcome, but merely designed to express disapproval or to punish people for where they live, only serve to further reduce trust in U.S. foreign policy more generally.

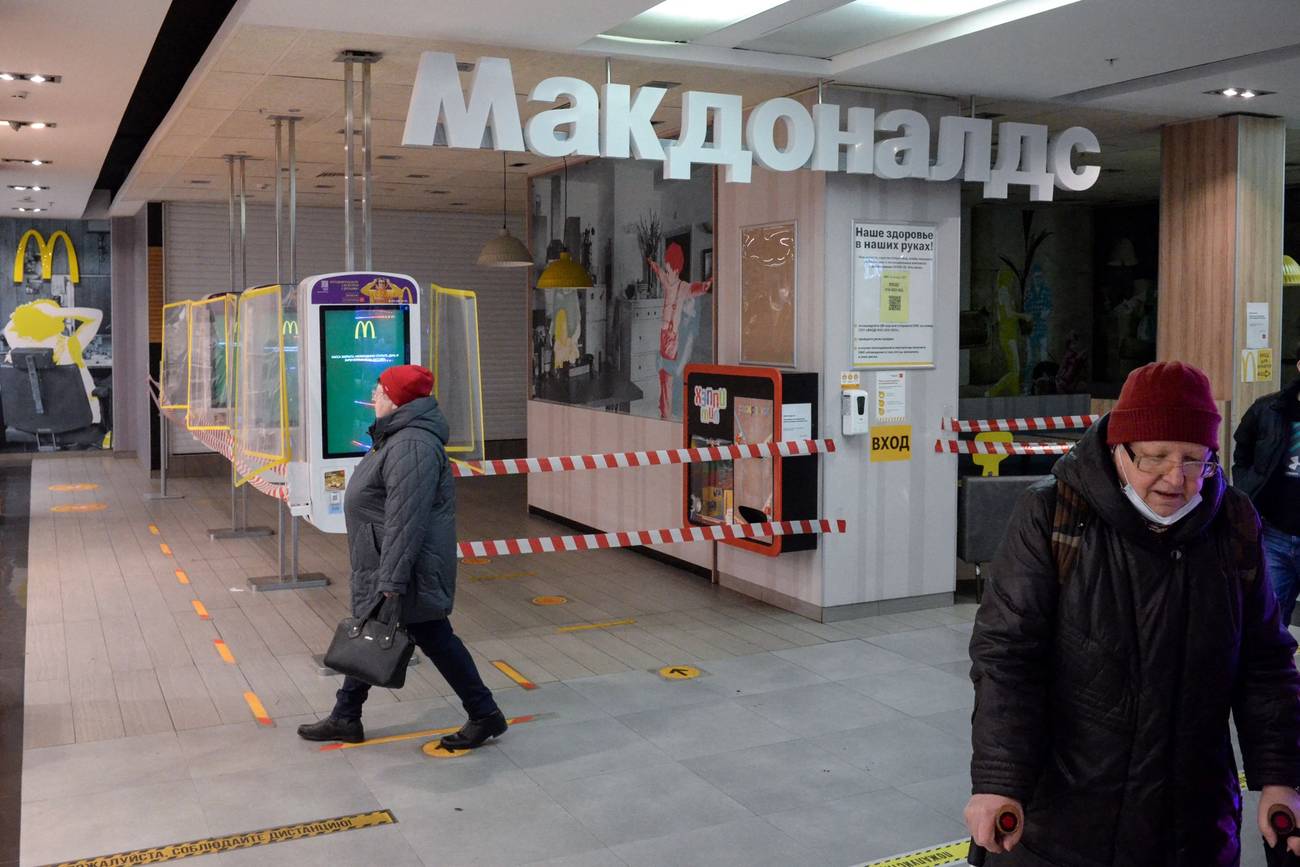

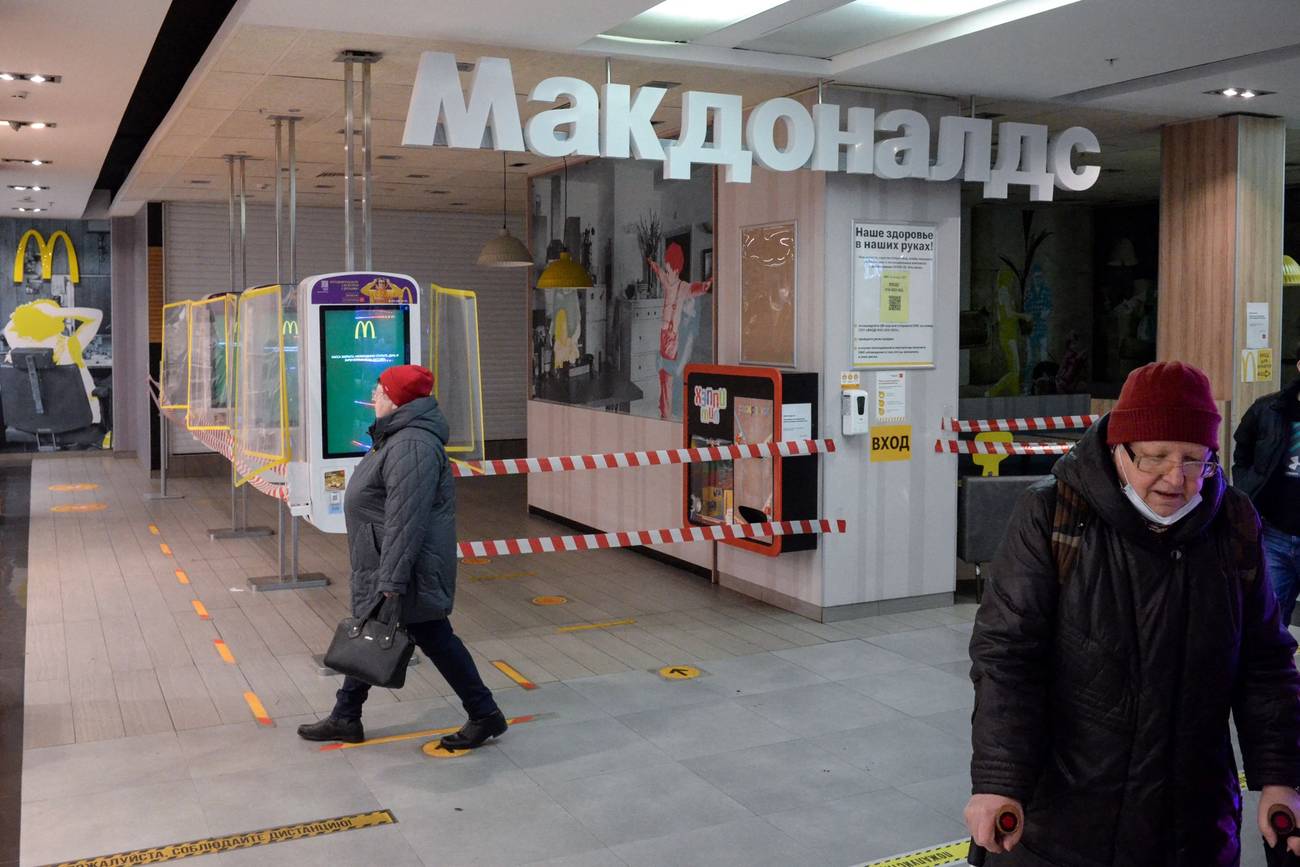

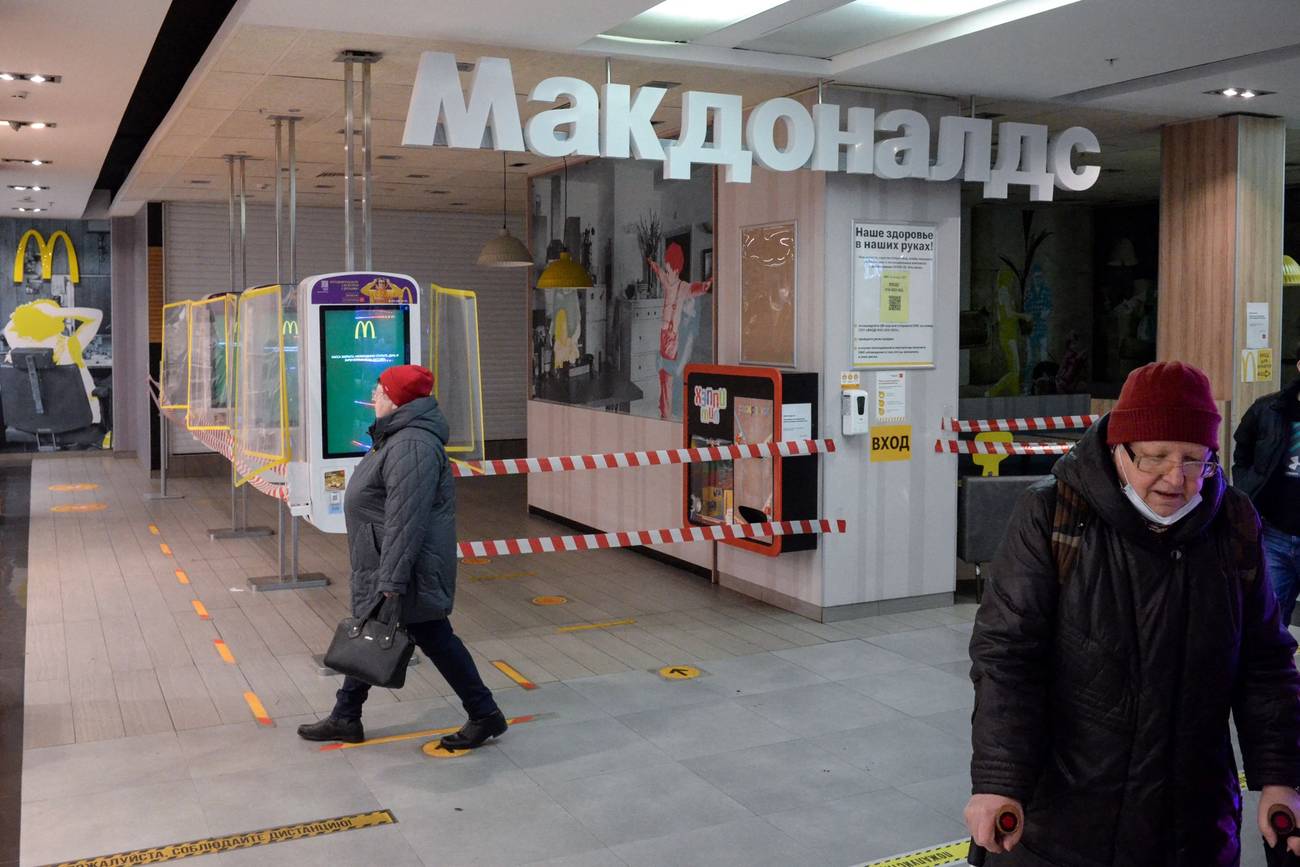

It was around the same time that apartheid ended in South Africa that the United States convinced Ukraine to agree to the 1994 Budapest Memorandum, in which Kyiv pledged to decommission its nuclear arsenal in exchange for Western security guarantees and Russian recognition of its sovereign borders. At the same time, Israel was committing to the Oslo Accords. Two decades later, it turned out not only that Russian promises amounted to nothing, but that Western promises were worthless, too. As soon as Putin started biting off pieces of Ukraine in 2014, we were repeatedly reminded that Ukraine is not a NATO ally, and thus we have no obligation to defend it against aggression. It is clear now that if Ukraine had retained even part of its inherited nuclear deterrent, Putin would have had to pick on someone else. Instead, in the first phase of the war, it mostly had to make do with the symbolism of McDonald’s withdrawing from Russia and Russian singers being kicked out of American opera productions.

In Israel, all of this sounds familiar. The stated basis of the “two-state solution” still favored by the Biden administration would require Israel to yield its major strategic asset: control of the Judea and Samaria highlands, which directly overlook the entire coastal plain. In exchange, Israel would get “recognition” from the Palestinians, solemn promises of nonaggression, and security assurances from the West. Let’s say Israel agreed. Is there any question that when war broke out again, those guarantees would be quickly forgotten, and we’d all be reminded that the United States has no mutual defense treaty with Israel? And what difference would cultural boycotts make in a time of war—either U.S. government boycotts of Palestinian institutions or U.S. private institutions boycotting Israel?

Perhaps the only lesson we can draw from the last few months is that while the United States, and the West more broadly, do not base foreign policy on any kind of consistent moral or legal principles, they do occasionally enjoy sanctions and boycotts as one-off ritualistic indulgences.

Eugene Kontorovich is a professor at the George Mason University Scalia Law School and the director of its Center on the Middle East and International Law. He is also the head of the international law department at the Kohelet Policy Forum, a think tank in Jerusalem.