Becoming Moses

Michael Freund is on a mission to lead millions of self-declared Jews home to Israel. What happens if he succeeds?

In the spring of 1997, shortly after Israel pulled out of its settlements in Hebron, Michael Freund was working at the communications bureau of Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, who was then serving his first stint in that office. The Diaspora Affairs adviser at the time worked across the hall, where mail to the cabinet was handled. The adviser and Freund kept what they jokingly referred to as “The Crazy File”: letters from across the globe from people who believed that they were the Messiah or who made oddball requests of the government. These were sometimes illegible, sometimes threatening, sometimes naïve and amusing.

One day, a secretary handed Freund a beat-up orange envelope, addressed to the Prime Minster of Israel. Freund opened it. The letter inside had been sent by the leadership of a community in Manipur, in Northeast India, which claimed to be a lost tribe of the biblical people of Israel. The rest of the letter was a simply worded plea to be allowed to come back to the land of their ancestors after 2,700 years in exile. They had written to Golda Meir and every prime minister since then but had never gotten an answer. Why not?

“I read it,” Freund says, “and I thought it was completely nuts.” Then, without really knowing why, he did something crazier. He answered the letter. What follows is the story of what he became, as a result.

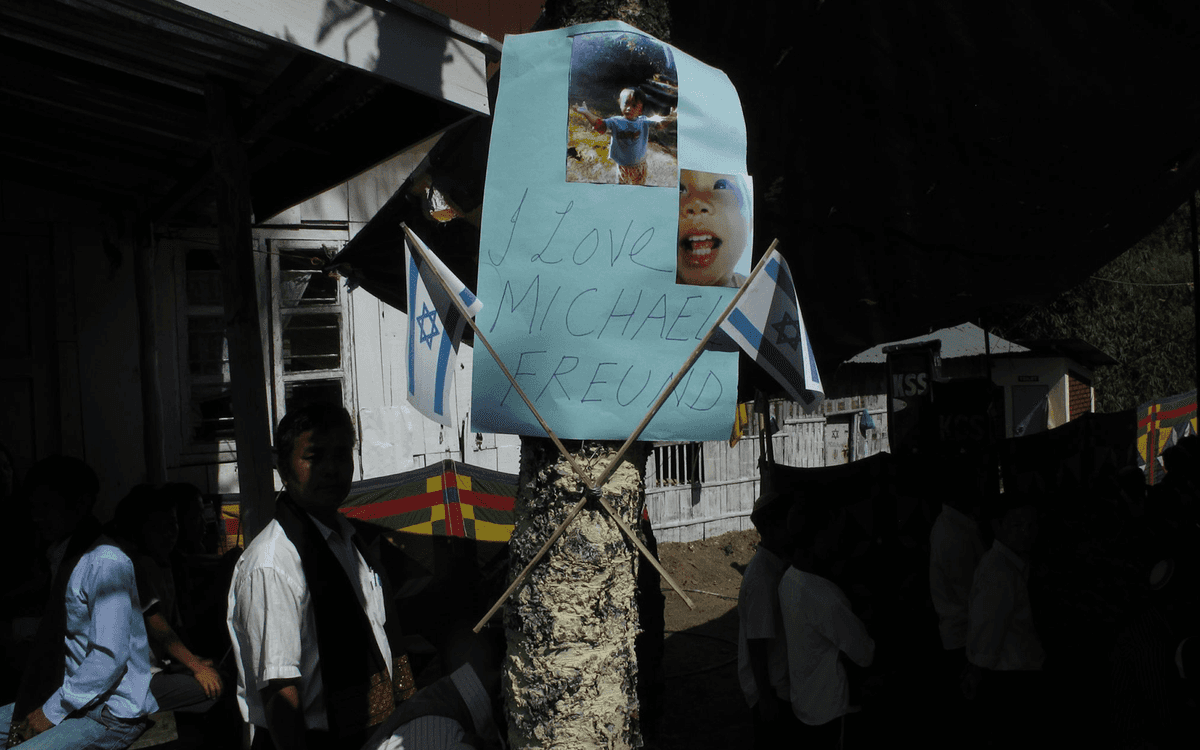

The palanquin on which Michael Freund will be lifted this November morning has been assembled from a cushioned tropical hardwood lounger, covered in tribal cloth and bunting, and lashed to a pair of stout bamboo poles painted silver. His porters sport dark turbans adorned with eagle feathers and a white sash across their brown torsos. Each carries a single chromatic grass pan-whistle, which they blow in time with the marching, boo-bee-boo-baaaa, as they hoist him shoulder-high above the crowd of several hundred Kuki, Paithe, and Thado men, women, and children waving small paper Israeli flags on sticks. A barefoot drummer leads the procession, and gong players trail. Freund’s legs dangle. The look on his face is a mix of mortification, embarrassment, and deeply satisfied delight: He wishes to honor the tradition that honors him, but he seems to realize that this whole scene is ridiculous, like something Werner Herzog if not Joseph Conrad might have dreamed up: the great white redeemer arriving to gather a remote tribal people, who shout, I low Michaew! I low Michaew!

Freund and his people are in the yard of Beith Shalom synagogue, in a town called Kangpokpi, across from the bazaar, in Sadar Hills, Manipur state, 30 miles from the Myanmar border. A faint smell of burnt rice fields, in full harvest, wafts in from the floodplains and terraces. The antlered, mounted head of a sakhi deer looks down from the pediment of a thatched proscenium, wreathed in a Star of David made of tied rice stalks. Along the short parade route, women hold handmade posters adorned with Israeli flags and scrawled with messages such as: “MAY HASHEM BLESS MICHAEL AND HIS FRIENDS FOR THEIR GOOD DEEDS AND MAKE THEM STRONGER.”

Freund is the guest of honor at a ceremony to celebrate Operation Menashe, through which, largely due to Freund’s efforts, 900 local hill people will make aliyah, or immigration to Israel, this year. Hebrew for “ascent,” aliyah represents both the ingathering of the Diaspora and the national aspirations of the Jewish State as embodied in the founding tenets of the Zionist movement.

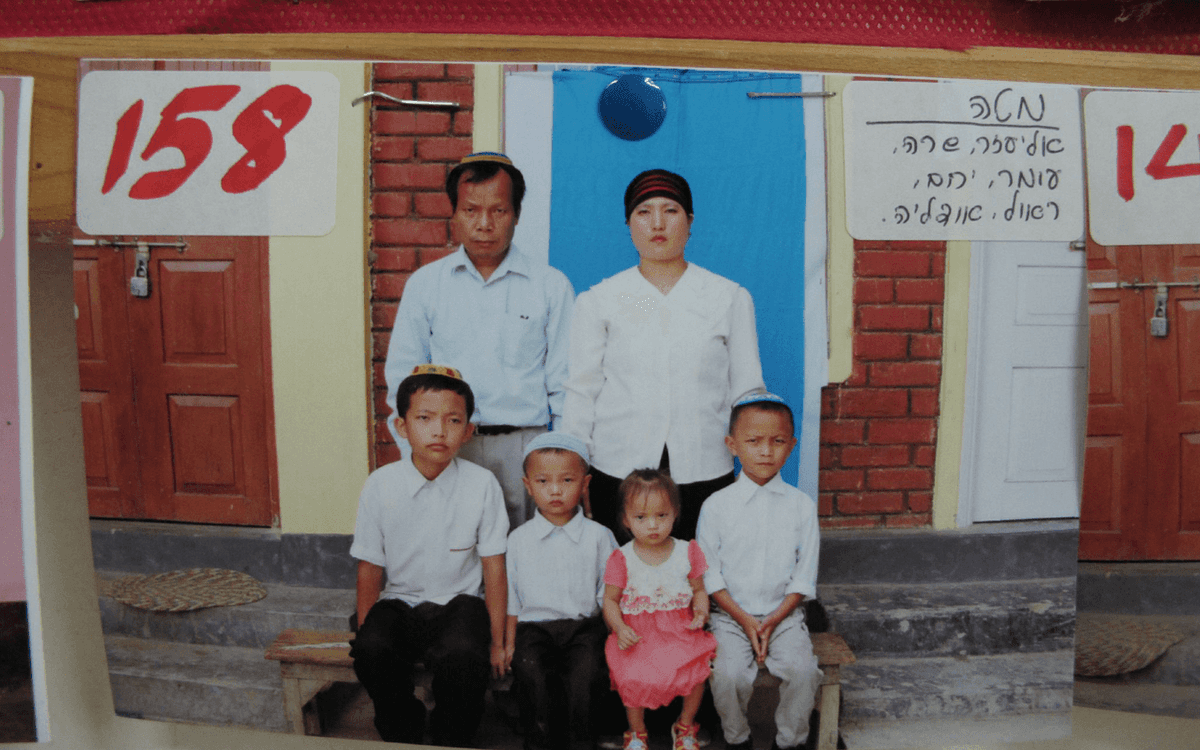

Freund alights and takes his place on stage along with tribal elders and envoys from neighboring villages. The crowd sits on benches in the yard, skirted women to the left, their heads covered; men to the right, most wearing hand-crocheted kippot. In the audience, a shirtless porter with an eagle feather snaps a pic on his smartphone, while a white woman, part of Freund’s delegation, aims a zoom lens at him. Bnei Menashe Council Chairman Avihu Singsit makes a welcome speech, calling Freund by his honorific, “Pu Michael.” The teens of the Kids’ Folk Action Songs and Dance Cultural Troupe of Beth Shalom Community Kangpokpi perform the Eagle Dance, with its barefoot agricultural gestures of digging, sowing, reaping, and gathering, boys and girls aligned, lightly coquettish. The girls’ forearms are wrapped in gold. A black vest handwoven in ethnic patterns is ceremoniously bestowed on Pu Michael, who before donning it sheepishly had only a silver Rolex to decorate his uniform of pleated black slacks, white Oxford shirt, and sensible black shoes. Looking mildly pasty and baggy from travel, he steps up to the microphone, flanked by a pair of tribal sentinels brandishing a sickle and a wooden sabre.

“We are living in the days of aliyah,” he says, staring into a sea of beseeching faces, as he delivers his words with the measured pace of a practiced speechmaker. “We are witnessing the return of the Bnei Menashe after 2,700 years of exile.” He pauses to allow a translation to Kuki-Thado, a lingua franca for the hundreds of dialects spoken by the many tribes of the Kuki, Chin, Mizo, and Lushai people of Assam, Bengal, Nagaland, Manipur, Mizoram, Kachin, and Chittagong. Applause, laughter, and cheering echo off the hills, after a short delay. “Abraham was the first immigrant to Israel, and you now are following in his footsteps. For 27 centuries your ancestors dreamed of the day when you would return to Zion,” he says. “You and I may not look alike, but we both share a Jewish soul, and that is what unites us. You are my family, I am your family, and together, with God’s help, soon we will march back to Zion.”

Shavei, which Freund founded in 2002 and which employs a dozen people full time and operates on a seven-figure budget, is dedicated to the discovery and recognition of “lost Jews” or “newly found Jews,” which include alleged descendants of the lost tribes of Israel, crypto-Jews, hidden Jews, and self-proclaimants. The non-profit works to reverse the 2,000-year-old inward turn of the Jewish people, who have historically thought of themselves as separate and insular. Shavei has “emissaries,” paid or partially paid employees, in India, China, Russia, Poland, Spain, Portugal, Sicily, Colombia, El Salvador, and Chile. From the central office in Jerusalem, Shavei is “actively in touch with” two dozen other communities around the world, from Ecuador to Zimbabwe to Kyrgyzstan to Indonesia to Japan to Suriname to Lithuania. Freund’s organization insists that there are Jews everywhere: You just need to know how to find them.

One of Shavei’s many ambitious goals is to put this global diversity, and the potential demographic explosion it represents, “higher on the agenda of world Jewry,” in Freund’s words. This is challenging precisely for the nebulous and heterodox nature of Judaism, which unlike other Abrahamic monotheisms has no patriarchate. Because the people Freund is interested in are at best no longer Jewish according to the more Orthodox of the interpretations of written and oral Jewish law, the idea of their return to the fold touches on a range of sensitive issues: Who should be allowed to join, or rejoin, a “chosen” people, and by what methods, and under whose authority? Underneath it all, there is a foundational angst: Who is a Jew?

As the Nazis and countless other persecutors in times past and present have made clear, the question of who is a Jew is not simply theoretical or theological. Being a Jew—not just identifying as one, but being recognized and perceived as one by others—has meant everything from insider privilege to the petty humiliations of country-club discrimination, from being a target for terror to being gassed. By finding living peoples with claims to Jewish lineage or identification, Freund is taking what could be a Talmudic parlor game and trying to force a nation to refine its boundaries: in or out, with or separate, diverse or homogeneous, growing or shrinking. Freund holds that contemporary Jews have a historical, moral, and religious responsibility toward their brothers and sisters, “lost to our people for so long.”

Freund’s reach is global, and he is a tireless peripatetic. In 2014 alone, he visited northern Portugal, parts of Spain, southern Italy, and Sicily, where he is working with descendants of anusim, who were forced to abandon Judaism against their will during periods such as the Inquisition. He prospected in Belgrade, Serbia, and the Republika Srpska of the former Yugoslavia (now part of Bosnia and Herzegovina). In Moscow, Russia, Freund met with representatives of communities of formerly Judaizing Christian sects known as Subbotniks (who also live in Ukraine, Armenia, and Azerbaijan, as well as Siberia). In Warsaw, he caught up with so-called Hidden Jews, descendants of Polish Jews who survived World War II by burying their identity in sheltering families or adoption schemes. He traveled to Kaifeng, in northern China, to check up on the small group of Chinese Jews there, some of whom have made aliyah to Israel and who trace their roots to Silk Road traders. Freund twice visited Manipur state, India, stopping off in Delhi to help with the continuing mass aliyah of the Bnei Menashe. He made a research trip to Frankfurt, Germany, and to nearby Mainz, Speyer, and Worms, home to many prominent rabbis in the period of the Crusades, when Ashkenazi Jews were unsettled—“and of course for the whole connection with the Holocaust, too,” he adds. Further afield, he was in Bogotá, Colombia, helping a new Shavei emissary trace what many believe to be widespread crypto-Judaism in the Americas, a legacy of the Spanish expulsions of 1492. And having seen a recent documentary about the Igbo people of Nigeria and their assertion of a possible Israelite ancestry—they are said to have migrated from Syria, Portugal, and Libya into West Africa around 740 C.E.—Freund decided he should go to Abuja and the southern Anambra State, to see for himself.

Between fundraising tours of the United States (and a vacation in the mountains of Switzerland, “just to breathe the crisp air and hike”), Freund also found time last year for classified visits to other places that may or may not seed future Shavei programs, where threats, or sensitivities, from host governments or neighboring religions make it prudent, he says, to do clandestine work. “I saw these communities out there,” Freund says, “and I also saw that no one was doing anything to reach out to them. I believed this to be a strategic mistake.”

That Freund sees millions of future Jews—fashioned out of past Jews—as a “strategic asset” is a reflection of a current of right-leaning political thinking in Israel that is both expansionist and optimistic. Though he states firmly that he does not believe in religious coercion, or trying to convince non-Jews to become Jewish, Freund cultivates ties with anyone who can claim verifiable historical connections to the Jewish people. “The more affinity that they have for Israel and the Jewish people,” Freund explains, “the more likely they are to sympathize with Israel and Jewish causes.” Bringing these exotics into the fold carries potential benefits in the fight against anti-Semitism in Europe, in positive propaganda for a modern state that welcomes and rewards dedicated immigrants, in the development of an Israeli workforce, and in tourism, once millions of people realize they have a more personal connection to the Holy Land than they knew. “And at the end of the day,” he adds, “a certain percentage of them will choose to come back and rejoin the Jewish people, so it will strengthen us demographically.”

The foundation on which the demographic-strengthening part of Freund’s plan rests is Israel’s Law of Return. Passed by the Knesset in 1950, not long after the founding of the State of Israel and in the wake of the Holocaust, the law states: “Every Jew has the right to immigrate to this country.” The Law of Return defines anyone with one Jewish grandparent as Jewish, a description that privileges the ethno-national component of “Jewishness” for immigration purposes; at the time the law was written, no major Jewish religious denomination accepted the “one grandparent” rule. While several dozen modern states have enacted rights of return to encourage far-flung diasporas to return to the homeland—including China, Finland, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Ireland, the Philippines, Poland, and Russia—Israel’s right of return has been controversial in part because of the widespread confusion, among Jews, anti-Semites, and ordinary folks alike, about whether Judaism is a religion, an ethnicity, or a nationality, or some uniquely Jewish combination thereof. Only late-18th-century French Huguenots once benefited from a religious right of return, and this was revoked after World War II when France feared that German descendants of French Protestants had become assimilated in Nazi Germany. Conversely, both Portugal and Spain have recently enacted laws allowing the descendants of Jews expelled during the persecutions of the 15th and 16th centuries to “return” to those countries as dual citizens.

Israel’s Law of Return shone as a beacon of hope to a persecuted people—and a promise of refuge. Ironically, over time, “every Jew” was found to be too restrictive a definition, if Israel was to fulfill its role as a sanctuary for all who were victimized on account of their Jewishness. In the 1960s, the Soviet Union and its allies in Poland singled out relatives of Jews for oppression and expulsion, as had the Nazis before them. So, in 1970 Golda Meir amended the Law of Return to include spouses, children, grandchildren, children’s spouses, and grandchildren’s spouses of Jews, which eventually opened the gates of Israel to 1.8 million Russians, Poles, and Romanians—hundreds of thousands of whom were not Jewish.

Meir’s amendments attempted to provide further legal precision to the thorny question of which “Jews” could make aliyah. How much of a Jew did you have to be, exactly? Section 4B states: “For the purposes of this Law, ‘Jew’ means a person who was born of a Jewish mother or has become converted to Judaism and who is not a member of another religion.” No one seemed to mind the tautology: A Jew is someone who comes from a Jew, or becomes a Jew. As Hillel Halkin—a journalist and writer whose 2002 book Across the Sabbath River tells the full history of the Bnei Menashe and their recent rediscovery before the arrival of Freund—points out, the question of who is Jewish is not one that often occurred to Jews in a political way until the 20th century. After Zionism, the horror of the Holocaust, the resulting Diaspora, and the rise of the Israeli state: Suddenly, strangely, after millennia of disadvantages, there could be advantages to being Jewish.

Freund, meanwhile, is not willing, he says, to put people’s dreams on hold while the Jewish world debates these points. By applying his fervent spiritual drive—and considerable earthly fortune—to answering the fundamental questions of Jewishness in challengingly concrete terms, Freund is pushing the modern Jewish state, and by extension the Jewish people, to shatter their self-identity. “Maybe he’s too young now,” his sister Rebecca Sugar says, “but in a couple of decades, people may judge him as one of the great leaders of the Jewish people of our generation.” The implications of his work—to Israel, to international relations, to modern Jewry—are enormous, and for some, terrifying and convulsive. If he succeeds, the face of the Jewish people will be transformed forever.

In talking about his work, Freund, who is 46, likes to credit his father’s mother, Miriam Freund-Rosenthal, who served for years as president of the American women’s Zionist organization Hadassah. Among other achievements, Freund-Rosenthal convinced Marc Chagall to create at Hadassah Medical Center’s synagogue what are now known as “The Jerusalem Windows”: brilliant stained-glass depictions of the Twelve Tribes, considered one of the artist’s late masterpieces. Freund remembers his grandmother’s stories about her work in youth aliyah, her trips to Morocco, Tunisia, and elsewhere in North Africa to bring young migrants to Israel. In the 1940s, she had helped raise money for the founding of Brandeis University and over her life endowed dozens of parks and clinics across the Jewish state. Whenever he gets the chance, Freund tells interviewers that his grandmother, holder of a doctorate in history from NYU, used to challenge him to wake up every morning, look in the mirror, and ask himself, “What am I going to do for the Jewish people today?”

In 1975, Freund’s father Harry founded the merchant-banking firm Balfour Investors, now headquartered at Rockefeller Center. Today, Harry and his partner Jay Goldsmith still specialize in “distressed investing and reorganization,” understated terms for what is referred to as “vulture investing”: buying up enough debt on bankrupt private mid-level companies to wrest control of them from unwilling owners in fierce negotiations and then turning the company around—often slashing jobs and overhead—and cashing out. (Harry Freund describes his work as: “Investing in companies that were troubled and trying to improve them.”) In the 1980s, the few players with the stomach for this kind of investing made fortunes under Reagan-era deregulation, both causing and profiting from economic volatility, including the market crash of 1987. In 1988, the New York Times dubbed Freund and Goldsmith “the bankruptcy boys,” practitioners of a “none-too-gentle art,” and admired their “New York brashness.” The pair told the Times that they were “reviving fallen angels.”

In a way, Freund does something similar—a kind of charitable inverse—but with human capital. Religious Zionism profits from Freund’s efforts, and more so now that the market definition of “Jew” is being exploded. And when Freund gets most animated—as when he says of his work that he’s “taking back what’s ours, reclaiming the people whose ancestors were taken from us, or left us, or were forced to leave us”—there is an echo of an uncompromising man. Rebecca Sugar says their father would have been a writer if her grandfather hadn’t been a demanding Depression-era financier. Later in life, Harry Freund wrote a novel, Love With Noodles, about an affluent Jewish widower on the Upper East Side he knew well—part Nora Roberts, part Bellow/Roth-pastiche. It might be ventured that while Harry created fiction loosely based on fact, Michael creates fact based on loose fictions.

Like his father and his younger sister, Rebecca, and their younger brother, John, Freund attended Ramaz, the Modern Orthodox prep school on New York’s Upper East Side. (Its Wikipedia page, below the section for “Notable Alumni,” includes the names of Isaac Herzog, head of Israel’s Labor Party and Bibi Netanyahu’s leading rival in Israel’s upcoming elections, as well as the actress Natasha Lyonne, along with a link to “List of investors in Bernard L. Madoff Securities.”) As a kid, Freund played the board game Risk and obsessed over baseball stats, especially those of his beloved Mets. Rebecca remembers her brother in high school as a “committed Reagan Republican and right-wing Israeli political thinker before it was in fashion”—something like Michael J. Fox’s character Alex on the TV sit-com Family Ties, minus the briefcase and the confused liberal hippie parents. Conversation at the Freunds’ dinner table often revolved around Israel, its politics, and Zionism.

Freund’s father says he remembers Michael as a young teenager standing on Mt. Carmel overlooking Haifa—on a father-son trip to Israel and Paris after Michael’s bar mitzvah—announcing his intent to become Sabbath-observant. But Freund traces instead the deepening of his faith to an influential rabbi at Ramaz, Yossi Weiser—who was “normal, in that you could talk to him about the Knicks and professional wrestling,” and a visit to the Western Wall, on a Jewish-group trip during high school. One Thursday not long after, at age 16, Freund took the train home to Westchester from Ramaz and told his mother that he had decided to keep the Sabbath. In reflecting on this decision in a column for the Jerusalem Post in 2010, Freund tells of lamenting his Saturday street-hockey games and missing Victoria Principal on Dallas.

By coincidence, the Torah portion the week of his decision was a famous one from Genesis, Lech-lecha, an exhortation to departure that can be translated literally as “go to yourself.” In it God tells Abraham to begin a great journey to an unknown destination. Freund realized, “I wasn’t really giving up a part of who I was, but instead recovering my true inner self.” That same impulse would later come to drive his work with lost Jews, whose “true inner self” may be buried by hundreds of generations of deceit, falsehood, or compromise.

Freund went on to Princeton, where he studied international relations and started an AIPAC affiliate called PIPAC (Princeton Israel Public Affairs Committee). After graduation, he spent a year in Israel, reading at a yeshiva in the mornings, and working in the afternoons at The Jerusalem Post for David Bar-Ilan, the illustrious concert pianist and Zionist icon who was then editorial-page editor and would go on to be the chief spokesman for Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu in his first term.

The following year, through a Princeton contact, Freund returned to New York as a speechwriter and aide at the Israeli Mission to the United Nations, under Prime Ministers Yitzhak Shamir and Yitzhak Rabin. These were heady times to be crafting speeches about Israel: Rabin signed the Oslo Accords with PLO leader Yasser Arafat in September of 1993. But a month before, in August, Freund had left his position to pursue a business degree at Columbia.

The year before, he had married Sarah Green, the Swiss-born, Brooklyn-raised daughter of Pincus “Pinky” Green—lieutenant to Marc Rich, the once-fugitive capitalist who was pardoned, along with Green, by President Bill Clinton in 2001—after taking her on a blind date to a Kosher Chinese restaurant. (Freund’s sister said, “That’s Michael: It didn’t dawn on him to try to impress the girl.”) Sarah Green was a Yeshiva University grad who was getting a Master’s at Columbia, and together they worked to finish up their degrees quickly, so that in 1995 they could move to Israel, with their firstborn son.

The young couple arrived at the Jerusalem home Sarah Green’s parents kept, and, with the orientation of established aliyah organizations that benefit U.S. citizens, lived there for a year. Freund took a job at Peace Watch, a right-wing monitoring group formed after the Oslo Accords by a pair of committed annexationists, including a former spokesman for the “Council of Jewish Settlements in Judea, Samaria, and Gaza.” Peace Watch’s reports helped factions of the Israeli right thwart Oslo as a political partnership; they were a favorite campaign tool of Netanyahu, who was elected in June of 1996.

When Peace Watch shut down, Freund moved to the foreign-currency trading room of the Sapanut Bank in Tel Aviv, and he hated every minute of it. “It afforded me no sense of meaning or purpose,” he says. But seeing a future in Tel Aviv, the Freunds decided to live in Ra’anana, a prosperous suburb with a large religious Anglo immigrant community. Two weeks later, Bar-Ilan called Freund and asked him to join the government of the newly elected prime minister as deputy at the communications office.

Freund had met Netanyahu before, while at Columbia, where after Oslo Freund had on his own initiative put together PLO quote sheets and sent them out by fax or dial-up Internet to whoever would read them. Some of these pamphlets made their way to Netanyahu, which led to a call and a meeting in a hotel room in New York, where the rising Likud star dazzled the Princeton grad with his grasp of political theory. So, when the chance came to work for Bibi, Freund jumped.

This was “right after the tunnel riots of October 1996,” sparked by one of the prime minister’s early anti-Oslo gambits: opening an archeological underground passage by the Temple Mount onto the Via Dolorosa in Jerusalem, an act that Arafat claimed was a “big crime against our religious and holy places.” From Peace Watch, Freund had a leg up on the legalistic language that was central to Netanyahu’s playbook for rolling back Oslo, which he openly despised and had campaigned against. Freund says that being in the corridors of power in the second half of the 1990s was a rare chance to see how governments function—“and don’t function sometimes.” As his term progressed, Netanyahu was besieged by marriage scandals and corruption charges, and his party lost both the pro-peace secular left, who clung to Oslo, and the hardline right, who saw the prime minister capitulate on borders and settlements.

When Netanyahu lost the 1999 election to Ehud Barak, Freund moved to the PR firm Ruder Finn in Jerusalem. It had none of the luster, let alone the “meaning and purpose,” he craved. His attention drifted to the stray seeds of the Jewish people: Freund had met with some members of the Bnei Menashe community, a small number of whom had been living in Israel since the 1980s, and then began looking into their claims more seriously and working on their requests. Eventually, he quit the PR agency, after asking himself, “Why don’t I just do what I love?”

“Bnei Menashe”—the name given in the 1980s to disparate groups of indigenous people, mostly in the Indian states of Mizoram and Manipur—derives from the belief that their legendary ancestor Manmási was the Hebrew Menasseh, first son of Joseph, born in Egypt, patriarch of half of one of the Ten Tribes exiled from the Kingdom of Israel in the 8th century B.C.E., at the time of the Assyrian conquest. How the children of Menasseh made their way through Persia, Afghanistan, and Tibet to these lush, hilly, rice-growing regions, over the Himalaya and across the Brahmaputra river, or down from northern Cochin China, is mostly lost to time, save for what ethnographers who have studied them describe as a deeply held belief in an ancestral homeland they were forced to leave. What is known is that these animists were converted to Christianity in 19th- and early-20th-century missionary revivals. The Bnei Menashe maintain that many of their traditional rites and rituals coincide with traditions of the Jewish people, and the lyrics of some of their songs refer to things that are mentioned in the Hebrew Bible.

In 1951, a tribal leader had a dream that his people would return to Israel. Studying books, some people there began to behave as they thought Jews should, adopting beliefs and rituals that they claim are more in tune with what they believed before Christian missionaries altered their culture. And then, through the interventions of intrepid rabbis and through their own resourcefulness, the Bnei Menashe became known to the wider world.

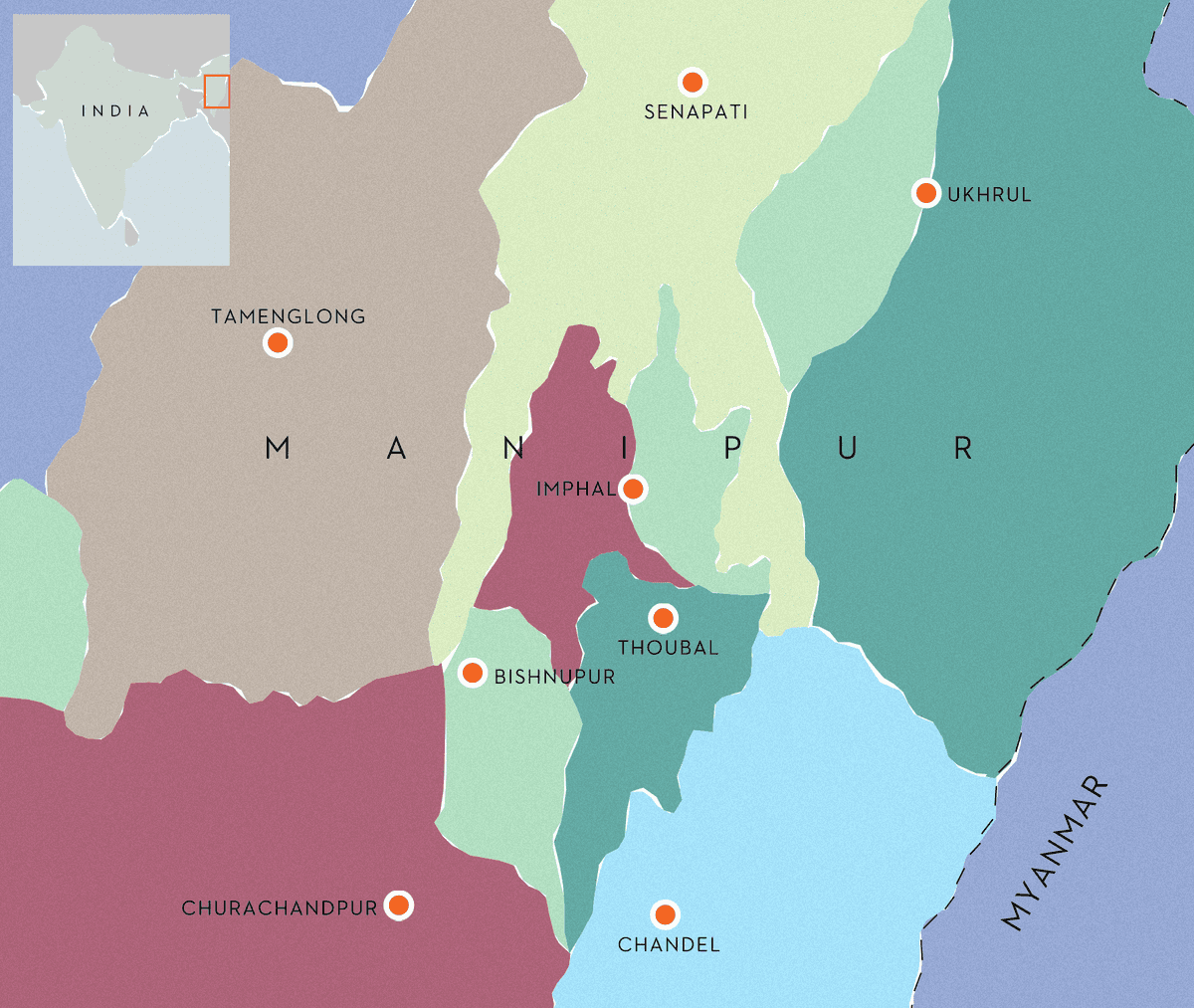

Today, some 9,000 Indians from Manipur and Mizoram describe themselves as Jews. Nearly 2,000 of them have moved to Israel, and most of the remaining 7,000 say they wish to. In the last three decades, they have built modest synagogues in dozens of villages and neighborhoods like Sijang, New Bazar, Matiyang, Gamgiphai, Zohar, and Old Lambulane, across the districts of Imphal, Chandel, and Tamenglong. They are subsistence rice farmers and low-level government employees, teachers, clerks, artisans, and owners of “tea hotels” and village food shacks. A few of the younger generation have local university degrees, but most have limited education. Many of the men have been circumcised as adults. They live in tight nuclear families in small houses and huts, and they walk to Shabbat services. Much of the Manipuri Jewish activity is concentrated around Churachandpur, a city of a quarter-million people. Not far from the central bazaar, down unpaved B. Vengnuom street, past the cane-sugar juice vendor and the outdoor meat stand, sits the Shavei Israel Hebrew Center, which has a well, no running water, a few classrooms, a pair of kitchens, and a second-floor sanctuary, where locals pray morning, evening, Shabbat, and holidays. Over the entrance, in a metal arch, are the words GATEWAY TO ZION.

Since the advent of Freund and his organization, Shavei, which has facilitated and encouraged their mass migration, the Bnei Menashe have been in upheaval. For years now they have been packing down their lives as Indian villagers and settling in Israel, 3,600 miles away. They describe Israel as God’s promised land, and for many that’s about all they know of it. The Tungnung family, for example—60-year-old Nianghat “Amalia,” 61-year-old Phangzalal “Daniel,” and their four children Lalminlian “Tzvi,” 27, Nemhoikim “Miriam,” 26, Lamneithang “Yosef,” 24, and Paulianthang “Benyamin,” 22—will be leaving their one-room shack in Songil village in two days, though the furthest any of them has traveled is Miriam for her studies in New Delhi. Elsewhere, others await their turn. “Israel” Hangsi is 45 years old, born in Kangpokpi on land his family has owned since 1924, around the time British missionaries built the still-functioning hospital in the teak forest above town. He reads the news at the radio station, translating English reports into a local dialect, for around 500 rupees, or $8, a day. “As long as I live here,” he says, “I have not fulfilled the 613 mitzvot,” or religious commandments. “Even if I wipe the floor there I don’t care. I’m an alien out here. I’m not treated badly, but I feel like an alien. Israel is the place where I belong.”

Back in Churachandpur, not long after his welcome ceremony, Freund’s 24-year-old driver, Paokhogin “Avihu” Haokip, takes out his Indian driver’s license and asks, “Will it work in Israel?” A pair of Israeli TV reporters, on hand to film the return of the Bnei Menashe, deliver the bad news that driving in Israel, though sometimes appearing to be chaotic, is regulated by rules, unlike in rural India, where there are no lines on the road—when there is a road—and where oxcarts, jeeps, bejeweled trucks, amblers, tuk-tuks, and sacred cows weave around potholes and bumps and occasionally land in ditches against trees. Haokip explains that his village chief wrote a letter attesting to his preparedness to pilot automobiles, and that the voucher was presented at the provincial licensing office, which emits the certificate without any sort of test, written or practical. Hearing this, and watching in terror as Haokip swerves out of the way of an oncoming truck, Freund says, “I’m thinking about how I’ve lived my life.”

Freund is on his way to Songil village, where his local field general, 28-year-old “Meital” Singson, has helped organize a reenactment of the traditional Kuki chicken-sacrifice ceremony for the benefit of Israel’s Channel 10. In a dusty courtyard, a dozen women and men, decked out in tribal formalwear of beads and wraps, are seated on woven stools around a ceremonial stick. The altar is rammed into the ground and adorned with a small basket, white chicken feathers, dried leaves, and curls of reed. Rice wine is sipped out of a gourd and passed around in cups freshly wacked from a thick stalk of bamboo.

The priest, an older man, speaks some words in Kuki-Thado and then uses his hand knife in a sawing motion to cut off the clucking fowl’s head. He smears some of its vital fluid on the stick. His assistant digs up some dirt and sprinkles it over the blood on the ground. Freund leans over to explain that what is on display is a relic of thousands of years of biblical continuance. There is great appeal—especially in a post-Holocaust world—in the idea that Jewish life and culture has persisted through the ages in muted or hidden forms, such as this, in far reaches of the globe. If an ember can be carried here in Songil village, an echo of a biblical sacrifice—through hardship and oppression, through concealment and confusion, through exile and migration—and is not extinguished, then with finding and fanning, the light of Judaism will never go out. The Jews of the First Temple followed a commandment to spread blood on the altar, and the Menashe have retained the rare biblical mitzvah of covering the blood of the slaughtered bird, now more commonly associated with the kaparot ceremony in preparation for Yom Kippur. No other local hill tribes spread dirt on the blood.

The ritual concluded, Freund bows before the dark-skinned priest with an eagle feather in his head-wrap. The man holds his palms open, like a surgeon after scrubbing, to retain whatever holiness is in them from their bloodletting. Then he gathers his hands on Freund’s nape, to bless him in a series of half-chanted syllables punctuated by eehhhhh.

Are the Bnei Menashe real? Or more precisely: Is their story true? In Holland a few years ago on a speaking tour, Freund was approached by some Dutch people who said they were descendants of the seafaring merchant tribe of Zebulon. Their evidence was that the Dutch are seafaring merchants, and that they knew in their heart of hearts that they were Jews. Identity, Freund answered, is not the same as status. The former is a matter of individual choice; the latter is dependent on others’ acceptance of that choice. U.S. census responders may list their race as Vulcan, but they aren’t counted as such. While Zebulons, and Vulcans for that matter, are free to define themselves as they wish—“Jews come in all shapes, colors, and sizes,” he says—they should not expect recognition from the State of Israel. For that, they’d need to provide “some serious evidence.” How else is he to know whether theirs is a struggle for authenticity or an act of desperation by economic migrants, or misinformed conjecture—or, worse, a ruse?

After the sacrifice, an apologetic Indian health official arrives and aims an infrared body-temperature gun at every foreigner’s neck, including Freund’s, to check for invasive fevers, insisting that it has nothing to do with the recent Ebola outbreak in Africa. The beautiful young women of the house serve Coca-Cola to the tribesmen and offer bead necklaces to the guests. A hand-painted sign above the door reads “Residence of Mr. T. Jebulun Jangkholun Haokip, Member Beith Shalom B. Vengnum, Judaism.” Jebulun Haokip, the day’s host, is 52. He has lived in this house, which he built of teak, for nearly 20 years. He dreams of moving to Israel. What will happen to it after aliyah? “I don’t mind,” he says, in the generous shade of a mango tree. “I love my home because it belongs to me. After, I will sell it. Then it belongs to another.” When his turn comes, he will leave the education department where he teaches language for 4500 Rupees, or about $70, a month. His sons are in Israel, he says, so they will work, while he will retire. For now he must await Freund’s call.

Freund is hardly the swashbuckling adventurer that his passion might suggest. Though his travels take him to corners where few tourists go, he can appear to be incurious, showing little taste for the perks of exoticism. His wife likes to joke that even on vacation in Europe, Freund will stand in the Piazza San Marco and, instead of admiring the pigeons and gothic architecture, he will point out that the Talmud was burnt there. In Churachandpur’s old bazaar, Freund stands horrified before a sack of farmed leaf snails and refuses every offer for a spicy snack.

And yet, to make good footage for the Israeli news camera crew, Freund has his driver pull over near Loktak Lake so he can help thresh rice in a field. On another occasion, he half accosts a woman returning from a well balancing a water pot on her head, to ask if he might try carrying it himself. On his way to a demonstration of Kuki traditional farming techniques, he stops the jeep to enter the open door of a woman’s one-room workshop and observe her at her seated loom as she shuttles the weft of a bright pink skirt. At Churachandpur’s Zo-Gam Art & Cultural Development Association Tribal Museum, with its dioramas, typewriter, Apple MacIntosh SE (“Showcasing the First Laptop & Computer used in Churachandpur,” reads the wall text), and replica Torah scrolls, Freund looks understandably flummoxed.

The ladies of the temple center—25-year-old Efrat Touthang, 21-year-old Karen Vaiphei, “General” Meital Singson—are accomplished cooks of a specialized hill-tribe regional cuisine: roasted black sesame seeds and ginger, foraged tangy greens, spiced stews, fragrant tree mushrooms, all served with tender local white rice. Touthang’s culinary sophistication extends to noting that the rice from the low paddies is softer and sweeter than the rice from dry terraces. In the kitchen of the Hebrew Center one day, seeing puri unleavened deep-fried bread being worked on a little Formica-topped puri-rolling stand, Freund thinks of when he was a kid, watching pizza dough being spun out: “The sweat gave it flavor,” he says. At dinner that night, Freund eats only a scoop of rice with water. When asked if he’s feeling OK, he says, “I feel fine, I’m just not feeling very adventurous.” Then he confesses that he packed Skippy peanut butter in his suitcase and has been eating it in his room all week.

In India, Freund appears most comfortable, and lively, in the confines of his faith: when he is in the sanctuary on the second floor, where he leads prayers and gives exegesis in a language and mode that is both didactic and familiar. Out among the tribe, in their homes, at their ceremonies, he becomes more nervous, picking at a side of his cheek, finding refuge in his cell phone. Though he’s always invited and expected on stage, in seats of honor, he likes to jump down and join the youngest children, gathering them in his lap and singing with them, playing games of disappearing or levitating kippot, and other language-less sight gags.

To achieve his goals, Freund spends a considerable amount of his own money. In both India and Israel, Freund declined to provide the specifics of his budgeting, but he admits he is the single largest funder of Shavei’s operations. He receives no salary and pays for all of his travel out of pocket. (“I’m blessed to be able to do it,” he says.) The most recent nonprofit filings for Shavei are from 2012, the first year of the renewed campaign to bring Bnei Menashe to Israel after a 5-year hiatus on aliyot. Some major donors are redacted, but the file specifies that 70 percent of 2011 donations, and 42 percent of those from 2012, are from a single board member—presumably Freund. The largest donation to the 2012 budget is in the amount of NIS 2.1 million, or roughly $550,000, which is close to 42 percent of the total income. It’s not unlikely this was Freund’s contribution that year—and that now that the Menashe aliyah is in full swing, his current charity could be double that.

In the case of the Menashe, Shavei covers the full cost of travel from Manipur to Israel, which comes out to about $1,200 per person, including airfare, ground travel, luggage, insurance, and paperwork. (Menashe are responsible for acquiring their own Indian passport.) For several years, until this year, Shavei alone had covered housing, food, clothing, Hebrew classes, “Jewish enrichment classes,” and incidentals during the migrants’ first three months at an absorption center in northern Israel, at about $3,000 per person. Recently Freund has negotiated a NIS 7 million ($1.8 million) shekel-for-shekel matching commitment from the Interior Ministry, which through petitioning has recognized that they should pay some of the absorption costs—despite the fact that the Bnei Menashe can only be Israeli citizens after their conversion—given that the ministry approved the migration to begin with.

Money aside, Freund is committed to the goals of Shavei and pragmatic about it, willing to work with whoever can help his charges find the Jewish fulfillment they seek. There is a selflessness in his actions, as if he were just the mouthpiece for some higher authority. He admires Menachem Begin as a militant who learned to compromise, citing Begin’s short book about his time in Russia—and his discussion of the KGB and Communism’s effect on Zionism—as an example of the broadest kind of geopolitics. Zionism’s goals are never achieved in a straight line, he notes. He understands that at this moment in Israeli statehood, the Orthodox rabbinate is the only authority with the power to sanction conversions, which means that it determines Israel’s immigration policy. That means that to get the Menashe into Israel, Freund needs to comply with whatever the Orthodox rabbinate requires of him. “I work within the system,” he says. “I don’t fight it. If I have to hold my nose in order to do good, then I do.”

In doing so, he shows a mix of his MBA, his experience in government bureaucracy and communications, the negotiating skills of a foreign policy maven, the can-do of the independently wealthy, and the fervor of Nathan of Gaza, the 17th-century Messianic theologian often depicted leading the Tribes of Israel out of exile. Freund practices “message discipline,” avoiding polemics whenever he can. On funding tours, he speaks to as many audiences as will have him. He appeared once via video, for example, for a full hour on Building Bridges, the talk show of Turkish Islamic creationist Oktar Babuna, to discuss the history of the Menashe, and other biblical topics. And if a prophecy floating around the Menashe holds that the Archangel Michael would appear as a redeemer, Freund is not averse to letting it ride. “I don’t like to talk of myself like that,” he says. “But if I arrived on time …”

The same principle seems to be behind his embrace of the support of Christian Zionists, many of whom have been active in the field of aliyah for years, in a dubious confluence of spiritual and political matters. Christian Zionists watch Freund’s progress with interest as he blazes a path to Israeli citizenship for people for whom the Law of Return is not an immediately apparent gateway to Zion. Shavei’s latest nonprofit filing in Israel lists significant donations from a number of prominent Christian Zionist groups, including Netherlands-based Christians Voor Israel; BFP International, a nonprofit partner of Bridge for Peace (described on their website as “Christians supporting Israel and building relationships between Christians and Jews in Israel and around the world”); and UK-based Ebenezer Operation Exodus, which sees itself as an “instrument of the Lord” for helping Jewish people make aliyah. More recently, Freund participated in a rally at Teddy Stadium in Jerusalem—organized by a Christian leader from Singapore, a hub of Asia-Pacific missionary work—that included 500 Bnei Menashe and also featured impoverished Holocaust survivors.

Not all of Shavei’s donations come from Christian Zionists: Last year, Freund convinced Keren HaYesod, the Jewish Israeli fundraiser, to tap its global donor base to assist with the immigration and absorption of the Bnei Menashe, a move that Freund describes as “a sign of growing acceptance of the Bnei Menashe among world Jewry.” By contrast, the Jewish Federations of North America and the United Jewish Appeal have so far declined to join the effort.

And there is cross-pollination, as Freund’s approach to the communities he works with can take on the cast of evangelical fervor. He is not a missionary—in Judaism, there is no biblical commandment or Talmudic law to turn non-Jews into Jews—but he is easily mistaken for one. “I wouldn’t plop myself down in Copenhagen or Oslo and start roaming the streets and convincing Danes or Norwegians to come convert to Judaism,” he says—Scandinavians being the least Jewish peoples he can think of on the spot. He’s ambivalent about the broader question of whether the Jewish people should try to convert non-Jews, though he recognizes the political and religious advantages to doing so. Unless the communities ask for it themselves, Freund does not believe in imposing his point of view that Israel is the place for all Jews to live. But when members of a community he works with express a desire to uproot, Freund has in the Law of Return an offer that is perhaps better than any missionary’s promise of salvation in the afterlife. He can offer the Holy Land—in this life.

When Freund first started working on behalf of the Bnei Menashe, he was surprised to find that there was not much enthusiasm in the Israeli bureaucracy for the ingathering of lost tribes. From 1997, when he made contact with the Menashe, to June 2003, he worked to get permission to bring a small number of migrants. But by the time a group arrived from Mizoram that year, Freund found that he had no allies in government. Ehud Barak’s new interior minister was Romanian-born Avraham Poraz, a member of Shinui: a Zionist, but liberal, secular, and anti-clerical party. As soon as Poraz got wind of the Menashe, he shut down the migration. Reflecting on the move recently, a decade after the fact, Poraz does not mince words: “It’s a bluff, a fiction. I do not know what their religion is. What I do know is that someone sold [the Menashe] an idea, a dream.” Poraz couldn’t see past the idea that they were economic migrants, using Judaism as “their chance to live a different life.” Why did Freund rely on Orthodox conversion only, instead of Reform or Conservative? And why were the Menashe being settled in the West Bank and Gaza?

Freund had no preference for Orthodox conversion under the Chief Rabbinate, except that it is and was at the time the only path to citizenship under the Law of Return: He’d be happy to allow the Bnei Menashe and other supplicants to convert halachically under other Jewish authorities, he says, so long as the government could provide some other path to their ultimate goal of residing in Israel as citizens. The second point was equally Kafkaesque: It took the Bnei Menashe the better part of a year to complete their conversions in Israel, during which time they were not Israeli citizens. Because they received no government support, the only places Freund could place them, he says, were communities in Judea and Samaria and Gaza, where religious settlers of the Gush Emunim school were willing to take on the burden of absorption out of ideological conviction.

Poraz was unmoved. “If you call them ‘Jews,’ ” he says, “you might as well say that half of the people in Africa are Jews. I’m not saying they are not nice, I’m just saying they have nothing to do with Israel, and they have nothing to do with Judaism. Therefore I decided to end this story. If we want to open the gates of Israel to anyone, fine. But why should we convert them?”

Frustrated, and with thousands of Bnei Menashe in India hoping to fulfill their dream of aliyah, Freund turned away from politicians like Poraz and toward the Israeli rabbinate. In 2004, he approached Sephardic Chief Rabbi Shlomo Amar, who had a history of favorable dealings with the kinds of populations Freund was engaged with, including rulings in support of the anusim of Portugal, and the Falash Mura, Ethiopian Christians who claimed their ancestors had been forcibly converted from Judaism by 19th- and 20th-century missionaries. In August of that year, Amar sent rabbinical emissaries to accompany Freund on a two-and-a-half-week research trip to Mizoram and Manipur. There, they met with Menashe, local Christians, historians, and Indian government officials before returning to make their reports.

A year later, Shavei was invited to meet with Amar, who formally recognized the Bnei Menashe as descendants of Israel and set down his decree in writing. But because of intermingling, assimilation, and isolation over the centuries, Amar required each Menashe to go through an individual conversion: He asked for a mikvah, or ritual cleansing bath, to be built in Manipur and Mizoram. And he agreed to send official rabbinical judges, or dayanim, to India, to carry out these conversions. “I decided to give them a clear Jewish right to convert and to make aliyah,” Amar says today, recalling his interventions at the time. “The people of Bnei Menashe are an integral part of the Jewish people.”

By then, Ariel Sharon, a figure much more sympathetic to Shavei’s cause, had taken over as Israel’s prime minister. In keeping with his idea of Zionism, Sharon took steps to formalize the conversion authority of the Orthodox rabbinate for all aspiring Jews, not just the Bnei Menashe, by bringing it into the portfolio of the executive. In August 2005, a rabbinical delegation flew to Mizoram with the plan to start conducting conversions on site. They had completed 218 of them before a local reporter, intrigued by the sight of bearded rabbinical judges in this far-flung corner of India, published an account in Web India. This was picked up by the BBC, and other places, which turned the trip into a diplomatic disaster: It turned out that no one in the Israeli foreign ministry had bothered to tell the Indian government that a formal delegation, headed by someone representing the prime minister’s office, was travelling to Indian sovereign territory with the express purpose of converting Indian citizens to Judaism, so that they could leave India and make aliyah.

India is not anti-emigration: Anyone with a passport is welcome to leave the country. But because of its history of religious wars and colonialism, it has strong anti-proselytism laws, with some Indian states expressly prohibiting religious conversions. With 300 more Menashe expecting conversion in Manipur, the delegation at the Hebrew Center in Aizawl, Mizoram, got an urgent call from the Israeli foreign ministry, telling them to leave without delay or else risk being arrested. As such, the 218 Menashe became the last group to make aliyah as Jews under the Law of Return. From then on conversions would take place only in Israel, or in friendly third countries.

In 2007, Freund got permission to bring 230 more Menashe to Israel. Ehud Olmert was then prime minister, and after a cabinet reshuffle, he had named Meir Sheetrit interior minister. It was like Poraz all over again: “From the very first moment I was totally against this story,” Sheetrit says. “I thought it was wrong to bring groups of people from different places in the world on the grounds that they are Jews.” Freund insisted that he had it in writing on Interior Ministry letterhead—and he had hundreds of people in India who had made financial and psychological preparations to emigrate. Shavei threatened legal action and through the help of Olmert’s aides was able to get the 230 Mensahe in. After which Sheetrit, in turn, shut down the immigration program. For the next five years, no Menashe made aliyah.

Facing a kind of political exile of his own, Freund spent the next five years petitioning Israeli politicians to re-open the gates to hopeful immigrants whom Israel’s rabbinate had declared to be part of the Jewish people. “I met with anyone and everyone I could,” he says. “Knesset members, ministers, their assistants. I told the story over and over and over again.” Nothing worked. In India, where he continued to visit at least once a year, the question was always, “When’s the next aliyah?” It broke his heart to have to keep telling them, “Soon.”

It took the return of Benjamin Netanyahu to the prime minister’s office, and the rise of his Soviet-born foreign minister, Avigdor Lieberman, who was also head of a ministerial committee on aliyah and absorption, to get things moving again. In June 2011, Lieberman invited Freund to present on the Indian case, which led to a resolution saying that in principle all Bnei Menashe should be brought to Israel. By October of 2012, after navigating the bureaucracy to get the “in principle” translated into “in practice,” Freund had a signed agreement to allow him to bring a group of 270, the first to come since 2007. To avoid repeating the controversy of sending the immigrants to occupied territories, Shavei opened a private absorption facility in Pardes Hanna, south of Haifa, and worked to find towns in the Northern District, such as Ma’alot and Carmiel, willing to receive the new Israelis.

That first group caused no documented trouble. In October 2013 the government passed another unanimous resolution allowing Shavei to bring 900 more. The first batch of 160 came in January of 2014. In May, Freund was awarded the $50,000 “Lion of Zion” Moskowitz Prize, alongside the founder of a jobs program for “displaced” Jewish West Bank settlers, and a Temple Mount archaeologist. Another 252 Menashe came in June. And 248 more came in November, with the remainder awaiting a return date in spring of 2015. (Freund notes that the number so far adds to 660, “which is Willie Mays’ career homerun record.”) Meanwhile, work continues toward a new resolution allowing Shavei to bring another 700 in 2015 and early 2016. The migration remains tightly controlled enough that the resolutions list individuals by name.

How many more waves of Bnei Menashe does Freund envision? “I imagine one day returning to this synagogue,” he says, sitting on one of the wooden benches in the Hebrew Centre in Churachandpur, “and taking the very last person who wants to come to Israel. There should be no one left behind here. And I dream of turning out the lights, locking the gate, and throwing away the key.”

Two buses will be leaving for the Imphal airport Sunday morning, one at 5:30, the other at 8:00. Because of Shabbat, most of the families have packed their two bags, weighed them, and locked them in a wooden shed on the temple grounds. After havdalah, the candle-lighting ceremony marking the end of the day of rest, Freund and a few companions take a walk around the block in the fading mauve light. After dinner, the community gathers for a raucous farewell party.

A sound system is installed and set to loud. Families are arriving from as far as 45 minutes’ walk away. Just as the show is about to start, Churachandpur’s power fails, revealing a moonlit village night with its distant echoes of barking dogs. The gas generator under the temple stairs coughs and heaves, and then it too gives out. Local power comes back, the next song is cued up on someone’s cell phone, and power cuts out again. LED hand lanterns are set out. A second engine is brought in from somewhere and hooked up to the synagogue’s electric box. “Welcome to farewell party for Operation Menashe, 2015,” says the emcee, a hazzan from the synagogue. “I would like to introduce Pu Micha—” Lights out. The crowd of a hundred displays extraordinary patience, or resignation. Freund, sitting on a couch on stage, is speeched-out anyway and says as much once the grid stabilizes, but the ceremony has been scheduled, and it will proceed.

M. Haokip gives a speech, followed by Pu Michael. The Cultural Troupe presents its eagle dance. (Before performing, a representative apologizes that preparations for departure have left them with no time to practice a new one.) A 6-year-old wearing a suit and tzitzit belts out a hammed-up karaoke version of a song written by “David,” who is already in Israel. To inspire his fellow Menashe, David had composed a power ballad about opening the Gates of Zion / the Ten Tribes will be together again—the boy is having trouble reaching the high notes, but his Menashe Idol shtick is golden. Everything is too loud, including the repeats of Katange! Katange!—“Beloved all Chin, Kuki, Mijo / Since time immemorial / We are the descendants of Manasseh / With one heart let’s all move forward”—which draw most of the kids up from their benches onto the stage, where much elated singing is captured for Israeli TV.

The Zo Peoples who live in these hills love ceremonies. It is unclear if this habit predates the founding of the Indian State, if the formality is a leftover of British rule or something more ancient. The resulting spectacle is a bastardized tribal gathering diluted by foreign modernity crossed with Jewish-summer-camp and evangelical-enthusiast aesthetics, along with a lot of unadulterated joy. In the temple courtyard, a carved and painted stele marks the “25th anniversary of Judaism.” Teenagers and young adults snap pictures on their phones. Will they soon be skulking around the back streets of Tel Aviv, squatting in a park like the Eritreans? Disoriented, afraid, angry, Kuki punks: From here, it seems unlikely. When the party is over, a rural stillness returns to the encampment.

In the morning Freund sleeps through the first departure. Before the second he heads upstairs to wrap and daven his morning prayers. Downstairs the hazzan is crying. General Meital is shuttling people to the waiting buses outside the metal Gateway to Zion, while Freund climbs onto the cargo rack to help load luggage. Nineteen-year-old Chonghoikim “Hanna” Touthang is crying, too, though she is not leaving. She says, “I experience separation.”

Amid the bustle, a bris is performed in the cement courtyard, on the benches of the previous night’s audience. The infant is named Daniel Yitzhak. Meital boards and counts family members from her clipboard. There is more crying: a pair of young women clutching each other—one must go, and one must wait her turn. When? How soon? Plastic flowers hang from the rearview mirror. Within 20 minutes, the bus is dispatched, rumbling down the dusty street, trailed by the bleating of an indifferent goat. Children crowd at the back window, waving through the mirrored red letters of EMERGENCY EXIT.

The history of the Ten Lost Tribes of Israel is littered with dreamers and doers, men who ventured and sought, invented and prophesied, drowned in their insane fictions or zealous beliefs—overcome by their faith, opportunistic, visionary. “Once declared lost, the ten tribes went on to create, time and again, the edges of the earth and the boundaries of the world,” writes historian Zvi Ben-Dor Benite in The Ten Lost Tribes. “They have conjured into existence whole places, such as Arzareth and Sambatyon; charted paths of supposed migration across the face of the earth; built land bridges between Asia and Europe and the Americas; inscribed real places with meaning and rendered them intelligible. The ten tribes have provided centuries of world travelers with itineraries and meaning. Whole peoples have been imbued with meaning through reference to them. They have promised the hope of redemption and humanity’s unity.”

In this, Freund owes much to his predecessor, mentor, and former partner Rabbi Eliyahu Avichail, an Israeli romantic who named the Bnei Menashe. Avichail represents a modern incarnation of an important branch of historical ten-tribe-ism in which the theological implications of both the losing and the finding of the tribes supersede any mundane concerns. In this view, the Bible and the prophecies related to the Ten Tribes provide “facts” as well as messianic signs that need to be both interpreted and audaciously acted upon. The prophecies point to a “final redemption” after at least three things are achieved: the restoration of the destroyed Temple in Jerusalem, the unity of the land of Israel, and the ingathering of the people of Israel, including the lost tribes. In modern Israel, this is reflected in the political philosophy of religious Zionism, a theocratic idea that tries to balance belief and patriotism. Religious Zionists from the Gush Emunim school of thought, out of which Avichail grew, believe the secular modern state has accidentally helped hasten the fulfillment of the biblical prophecies by virtue of its very existence. Settling the West Bank and, formerly, Gaza, is a step toward “repopulating” lands that holy scripture describes as once belonging to Jews. Ingathering of the Lost Tribes is another such step.

To end the exile, Avichail was determined to track down the tribes in the form of their descendants and to bring them “first back to Judaism,” as he wrote, “and then to the Jewish People and to the Land of Israel.”

In 1975, Avichail presented his amateur scholarly research and biblical sources for the scattering of the Lost Tribes to his influential teacher Rabbi Zvi Yehuda Kook (1891–1982) at Kook’s Merkaz HaRav Yeshiva. Kook and his father are largely responsible for the modern religious settlement movement in the West Bank, and when the press speaks of “the religious right” that builds houses in Judea and Samaria—and battles Israeli forces when they are declared illegal and torn down—they are often referring to Kookists without naming their spiritual leader. After Avichail had spoken on his text-based discoveries about the Pathans of Afghanistan, Kashmiri Jews, the Karen, Shinlung, Chiang-min, and the Beta Israel of Ethiopia—with evidence for these and other remnants of the exiled Ten Tribes in Japan, the Caucasus, and elsewhere—Kook had said, “Talking is nice, but it’s not enough. You must act.”

Avichail complained that he lacked resources and was just a humble teacher himself: “What do you mean, ‘act’?” he asked. In the manner of great Talmudic teachers, Kook would provide no further explanation.

But Avichail was a spiritually committed and devoted follower. He had left Israel only once before in his life—in 1956, to meet the family of his French wife, who survived the Holocaust thanks to Kindertransport. Over the next 30 years, he embarked on a series of insane adventures: to Pakistan, Kashmir, Szechuan, Thailand, India, Burma, Japan, Georgia, Azerbaijan, Portugal, Sicily, Majorca, Peru, and Mexico, to put his theories to the test. He found the Menashe, studied their traditions and beliefs, and began to bring a few of them to Israel. His travels often revealed what he hoped to find, and this in turn made him ever more obsessed. He made it his life’s work: Avichail founded a tiny organization consisting of his wife, Rivka, and a volunteer assistant and named it “Amishav,” my people has returned.

In 1997, Freund asked Avichail, whom he had read about in news clippings, to meet him at the prime minister’s office. Over the following two years, Freund became more and more involved with Amishav as Avichail’s advocate in the halls of power. Up until that point, the amiable but scattered Avichail had worked out of his living room. Freund, the government official and Wharton MBA, began to establish more of an organizational structure. He rented an office for Amishav, hired a minimal staff, and began making trips of his own, starting with a visit to anusim in Barcelona and Madrid.

In January of 2000, Avichail managed to get himself invited to a meeting of the Knesset’s Committee for Immigration, Absorption, and the Diaspora chaired by Likud MK Naomi Blumenthal (who was later convicted on corruption charges). His goal was to convince the council to allow the immigration of a few hundred Menashe. Blumenthal called the Menashe “most positive … they are certainly creative people who feel a connection to Judaism. … However, the moment we give a small opening, another million people may come and claim: If they have the right [to return to Israel], so do we.” She added, “Regrettably, we have negative experience with Jewish organizations, mainly from the United States, that are beginning to portray us as a country that does not want immigrants who look different or have different outlooks than us because we are a racist state.” This led to an exchange between the former director general of the Immigration and Absorption Department of the Jewish Agency for Israel and a Knesset Member for the ultra-Orthodox party Agudat Yisrael. The minutes of that reveal a lot about what was—and remains—troubling about the idea, and what made Avichail’s work that of a Hebrew Quixote:

Yehuda Dominitz: Since Rabbi Avichail and other rabbis came to us arguing that we must return the Ten Tribes to the Jewish people, I went to speak to Rabbi Goren who told me then, “If you bring one person, it’s really a matter of millions.” I think that it’s clear to the members of the Immigration and Absorption Committee and other government agencies, that approving the immigration of 100 to 200 will optimistically turn out to more like 1.5 million and more optimistically, 3 to 4 million people.

Shmuel Halpert: Five million.

Yehuda Dominitz: But moreover, Rabbi Avichail spoke to me more generally, not just about Jews from Manipur, but also the Harpetanim in Afghanistan, who also number a couple million. For me, from the perspective of the Ministry of Immigration, I saw this as a major problem. […]

Shmuel Halpert: I thought, naively, that Rabbi Avichail would present scientific and historical evidence that this tribe is Jewish, backed by evidence and proof. From what I’ve heard so far, the whole thing is based on a dream that somebody had that he was part of the tribe of Menashe, and even that is doubtful. There is some song—“Amansi,” which might refer to Menashe. The whole story seems a bit fictional.

Avichail is now in a nursing home in Jerusalem. He suffers from advanced Alzheimer’s. His wife Rivka says her family “paid a big price” for his ambitions as he spent his meager teaching salary on trips and made himself a subject of ridicule—including in what she calls his unfavorable portrayal in journalist Hillel Halkin’s book about the Menashe. “People said that my husband was crazy,” she says. “But I believed in him.” She says Freund was the first representative of the Israeli government Avichail ever met who took his pursuits seriously. Freund delivered on promises to help get immigration quotas for the first Menashe. But he and Avichail soon began to recognize differences in what they hoped to achieve, and how they hoped to go about it.

The idea of the great redemption that had begun with the resettling of the land of Israel and the ingathering of the Lost Tribes became in Freund’s hands more like a bureaucratic maneuver, a “process” with “belief systems” within a “political reality”—as if what God needed was not an eccentric visionary, but a dependable, deep-pocketed accountant. Avichail insisted on staying focused on representatives of the Lost Tribes. After his experiences with the anusim, Freund wanted to expand Amishav’s brief to the descendants of Jews, known and unknown. Why limit the work to biblical migrations when in the course of Jewish and world history so many other cataclysmic disruptive forces had caused wounds that had not healed? Why bring only some lost Jews home? Freund wanted to bring in funding from whoever wanted to provide it. Avichail refused to take money from Christian Zionists, fearful, his wife says, of their real goals. When Freund branched off and created Shavei, the split was very hard on both men. Had Freund stolen Rivka’s husband’s life project? “He didn’t want to say it,” she says of Avichail, “but the feeling was there.”

Avichail collected most of his findings into books, and many were translated into the languages of their subjects, as well as French and English. The capstone is a 2004 book, under his own Amishav imprint, titled The Tribes of Israel: The Lost and the Dispersed—a sequel to The Lost Tribes of Assyria—which catalogs 50 years of personal investigation into the whereabouts of the descendants of the Hebrew tribes. The preface acknowledges a number of collaborators and supporters, closing with “A blessing to them all.” There is no mention of Michael Freund.

“I’ve been doing this 17 years,” Freund says. “I had hair when I started, and”—lifting his kippah to show his pate to the migrants gathered in the basement of the Fortuner Hotel in New Delhi—“now I have none.”

The joke is duly translated for the tired families, members aged 1 to 72, who have spent the entire day in the hotel. For many the trip to New Delhi is their first to the national capital, for most their first time flying, and for more than a few their first trip beyond Churachandpur and its surrounding hills. Earlier in the day, a dozen Manipuris ventured on a walk to nearby Jafar Market to purchase some essentials, maybe a pair of shoes. Though there is no credible threat to the Menashe in tolerant India, the group is shepherded by three young men from the Bnei Israel community of Mumbai Jews, security personnel trained in Israeli defense techniques, with a vague notion about Islamists or “Muslim extremists.” The men, noticeably more corpulent and taller than the Menashe, are volunteers from the Mumbai synagogue of the Indian-Israeli travel agent Malka Moses, who handles all the tickets and Indian hotels, as well as the paperwork from the Israeli embassy. She laments that past migrants to Israel—Yemenis, Moroccans, Ethiopians, her own people from Bombay, and formerly from Iraq—are no longer like what the Bnei Menashe seem to her now: “They are grateful. They do the job they are given. They don’t complain. More like what we used to be.”

As Freund helps the Bnei Menashe fill out their diplomatic chits, matching pristine Indian passports to ticket numbers and official rosters, Moses tells a brief generational story about how the Hindu Brahmin are actually Kohanim, the biblical priestly class, and how the entire social order of India is a mutation of that Jewish origin. She speaks with unwavering conviction and then excuses herself, as Freund has finished and has now given the floor back to her. She informs the olim, or religious Israeli immigrants, how to handle the one-way ticket out of India they will be given the next day at Indira Gandhi International Airport. “They will ask why you have no return flight,” she says, “and you will show them this piece of paper. Do not worry.” She lifts a sample on the tripartite letterhead of the State of Israel, the Department of Population Registration and Status, and the Population and Immigration Authority. It reads, “To Whom it May Concern: The Interior Ministry of Israel confirms that the following list of individuals have been allowed to immigrate to the State of Israel.” Moses then concludes with some uplifting words about being in the Holy Land this time tomorrow night. When this news is translated, one of the older men bursts into a half-toothed smile, red with beteljuice, a lump of chewed leaves in his cheek.

Yosef Tungnung is feeling relaxed, he says, but not everything has met his expectations. “I thought Delhi would be very clean,” he says. “It’s dirty and very noisy.” The only part of this roiling center of trade and government, mess of humanity, glorious spice-and-filth chaos, that he has seen, is Jafar, where he purchased a pair of knock-off high-top sneakers. His mother carries with her 50,000 Rupees in cash, or a little over $800. This is money his father borrowed against a pension he will one day be due from his $300-a-month salary at the provincial fish hatchery. Part of that money paid for the family’s passports. “I wouldn’t be able to afford to even stay in this Fortuner hotel,” Tungnung says. “One night, it costs a lot. We are going under Shavei, feeling very lucky.”

The next day, the Menashe olim fly out of Delhi’s smog to Amritsar, the Sikh holy city of Punjab, built around the Golden Temple and its shimmering reflecting pool, which is visible from the sky. Across the plane aisles, in first class, Freund straps a black box to his head, ducks under his prayer shawl, and rocks silently over a travel-sized leather-bound prayer book. Out the window, the Himalayas rise over a brown layer of harvested rice fields and another of smoky clouds. On the airport tarmac, 50 kilometers from Lahore, and even closer to Pakistan’s border, five armed Indian fighter jets sit with raised canopies, ready for pilots. The plane then takes off again and cruises over Tora Bora and Khyber Pass and Kabul, around the Pamir and Allay ranges, over the Silk Road hub of Samarkand, and into Tashkent. If their story is true, then in just a few hours the Bnei Menashe have covered ground that took their ancestors millennia to cross.

In the Uzbeki capital’s airport, many of the children fall asleep on makeshift beds of hand luggage. The youngest remain strapped to their mothers’ backs with cloths of vivid colored prints. An older man keeps his bamboo pipes in a red plastic bag, his only carry-on. An older woman has cotton in her ears, a folk remedy for cabin pressure. Benyamin Tungnung, whose first experience of flight was the day before from Imphal to Delhi, marvels at the automatic faucets in the airport’s renovated bathroom: “When we wash at home, we use the well,” he says. “But here you just put your hands and water comes out!” He is equally amazed by the hand dryer and the moving walkway. Freund spends most of the layover catching up on emails and news on his phone, before afternoon prayers in the terminal: a spectacle of bowing, Westward-facing men that draws the attention of the Asians, Russians, and Israelis in transit.

In the lone airport café, some Israeli senior citizens returning from a tour of India want to talk with a young Menashe. He explains in English that they are making aliyah.

“Good for us! Good for you!” says one Israeli.

“Have a good life in Israel!” says another.

The shyly smiling Indian says, “For us it’s first time.”

One of the retirees then turns to her companions. “We have 150 families of them in our village,” she says. “They are very good with kids.”

After midnight, exhausted and excited, the olim descend the airstairs off Uzbekistan Airways onto the Tel Aviv tarmac, waving into the bright light of Israeli TV. Freund coaches them to show their enthusiasm for the cameras. The security officials who seemed stern on first glance transform into greeters as well, leading the Menashe and their handlers onto an airport bus. One steps aside to kiss the ground. People break into song—Am Yisrael chai! Shavei Israel chai! Bnei Menashe chai! and deflated renditions of their anthem, Katange. At passport control, Freund meets with four Papua New Guineans, there to “see the process of how the immigrants come.” Freund says to them, “I was thinking of seeing the Gogodala next year,” referring to a grass-skirted and shell-goggled jungle people that the Internet showed singing the holy prayer Shema. “Is that real?”

Upstairs, at the immigration center, which resembles a DMV with free sandwiches, families are called up one-by-one for formalities. The walls are decorated with images of past migrations: of the 4,515 illegal immigrants to Palestine on the ship Exodus 1947; Ethiopian Beta Israel, gaunt and scared, in the hold of a cargo plane during Operation Moses in 1984; refugees dancing by canvas tents at Ein Ganim in 1940. A medic takes care of a Manipuri girl who has a light fever. Stubble now showing on his face after nearly 24 hours of transit, Freund makes one last ceremonial speech, thanking the State of Israel, and leading everyone in the national anthem, “Hatikvah.”

Sofa Landver, minister of Aliyah and Immigrant Absorption, made aliyah herself from Leningrad in 1979. It’s fitting that her Russian first name, when pronounced as Hebrew, means “grandmother,” as she’s here at 1 a.m. in Ben-Gurion Airport’s Terminal 1, doting on the Menashe children, handing out packs of candy and toys, posing for news photos with the women in their khiba bead necklaces and the overlarge, cheap, white printed T-shirts that Shavei has given to each of the new arrivals—the first tiny step in their long, slow deculturalization and assimilation. After a short welcome speech translated from Hebrew to Kuki-Thado, and in between leaving red lipstick marks on coffee-skinned children, Landver declares herself committed to bringing all of the Bnei Menashe home. Once the Israeli government decides on their fate, she adds, Subbotniks from across the Former Soviet Union would be next. She praises Freund’s perseverance in India and says of the Menashe, “We hope that they will settle in Israel as real Jews.”

Freund heads home to Ra’anana. The Menashe are loaded with their things into waiting tour buses and driven three hours north to their absorption center, where the sun will rise on their first day in Israel.

Kfar HaNoar Hadati, adjacent , is a one of dozens of youth villages, or boarding schools, first developed in Mandate Palestine in the 1930s to care for children and teenagers fleeing the Nazis. The collection of modest cement buildings is now Shavei’s arrival camp for the Bnei Menashe, as well as, separately, a boarding school for new Ethiopian immigrants. A functional replica of a gojo grass-roofed Ethiopian hut stands in the schoolyard. It isn’t clear if the structure is an expression of pride or a device to soften culture shock.

Menashe families spend three months on the campus. They shop or visit nearby town centers and friends and relatives, if they can afford it. They have their Indian passport but no return ticket, nor many shekels. They study, hang out, pray, and are fed at the school cafeteria, where they take turns on clean-up duty. Because of the long stay, most unpack their suitcases into the closets in their dorm rooms, which have private bathrooms and bunk beds. The center is run by an affable former industrial caterer and utility man named Shlomo Sherwood, assisted by acculturated migrants from previous years. In his office, waving at a bulletin board full of labeled photographs of each Menashe family taken in the Hebrew Centre, Sherwood laments that they are running out of towns to place them. In each room, Shavei provides mini-household kits covering cleaning needs (broom and dustbin, mop, jug of floor wax, bucket, rags), personal hygiene (4 toothbrushes, 1 tube of toothpaste, 1 bar of soap, 1 large bottle of shampoo, 4 rolls of toilet paper), and domesticity (1 bottle of laundry detergent, 4 hangers, trash bags, 2 new white towels, 2 sets of single sheets per bunk bed). The hallways feel like a Jewish sleepaway camp crossed with a typhoon shelter after the storm—with the same aimless wandering and sitting and confusion about what to do next. At night, metal shutters leave the rooms in total darkness and silence.

During their second day in Kfar Hasidim, family by family, the Menashe enter Classroom 4 and sit in school chairs opposite gray-bearded Rabbi Yehuda Gin, who is part test proctor and part advocate. He has set paper plates of wrapped candies and two-liter bottles of soda on the desk. Gin is not officially licensed by the conversion authority, which used to be part of the prime minister’s office and was recently moved to the Religious Affairs Ministry. His role is to check the level of preparation before each family faces the rabbinical council for their official giur, or conversion. (Freund notes that for many of the groups he works with, including the anusim, the Jewish connection goes back so far that their “reclamation” is “not just a matter of ‘religious conversion,’ ” but “something closer to confirmation or affirmation”—ceremonies the Jewish rabbinic system is not equipped to handle.)

The testing is friendly. Gin, in accented English, asks, “What will you do? You were a nurse before?”

The father says, “I will work to improve the country.”