Being the Jew in the Box

To have conversations with Germans about Jews, I had to become an exhibition at Berlin’s Jewish Museum

It’s not often that someone compares you to the Hottentot Venus, Tilda Swinton, and Adolf Eichmann, all in the same hour.

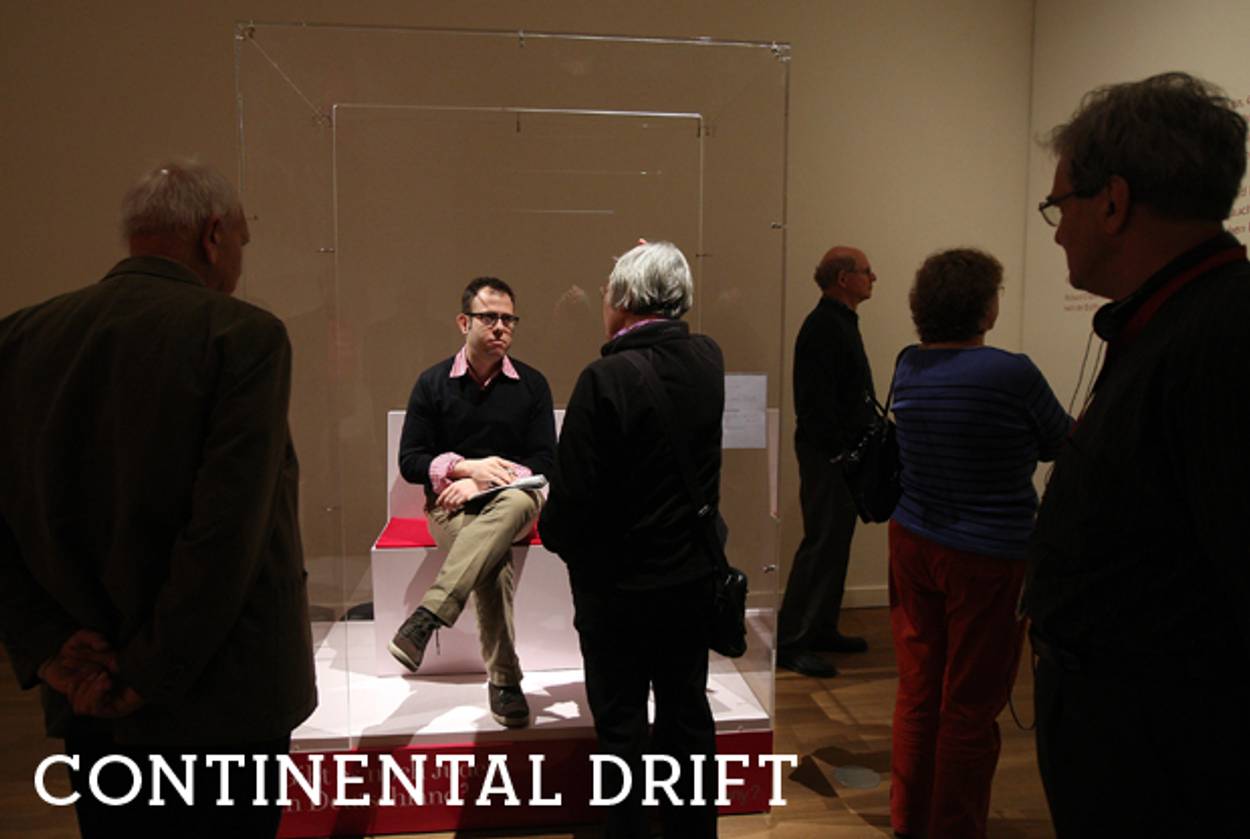

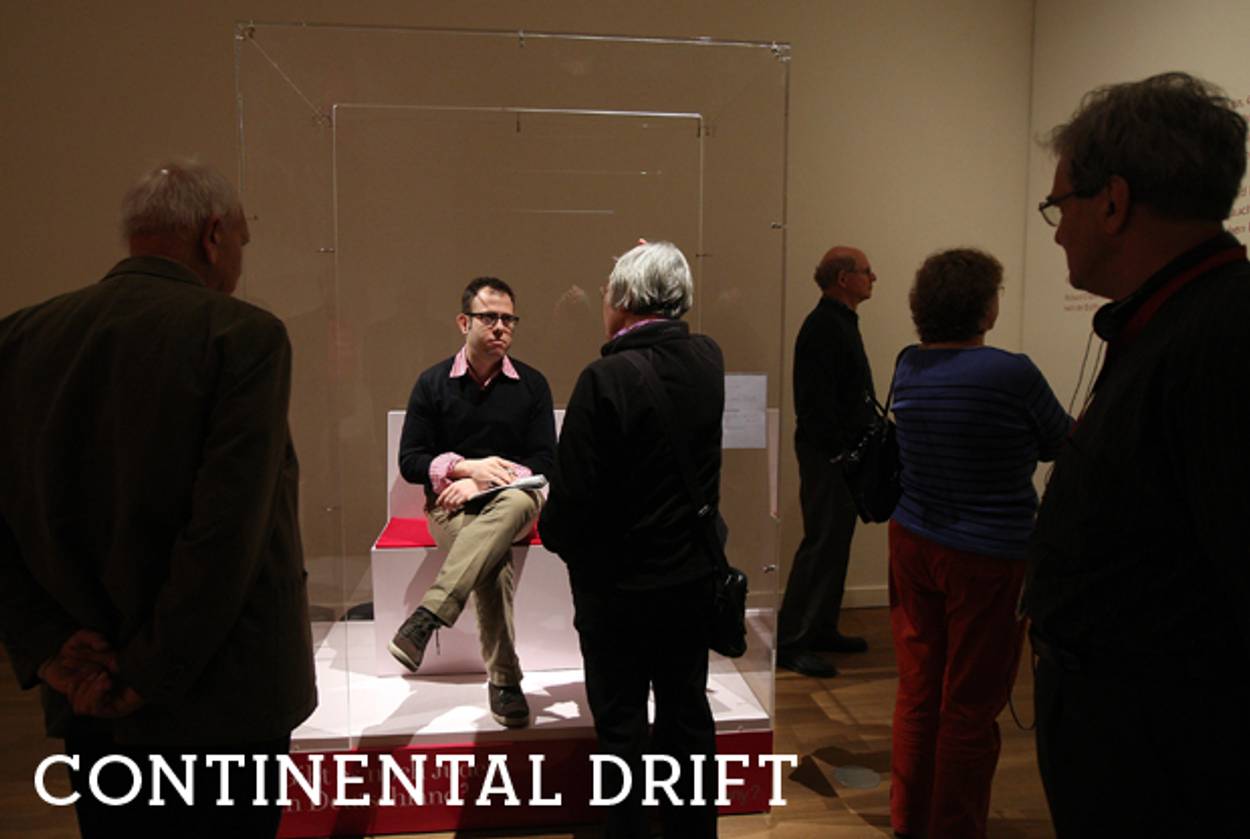

But yesterday, depending on your point of view, I was all three. In the week since the Jewish Museum in Berlin unveiled its controversial exhibit “The Whole Truth: Everything You Always Wanted To Know About Jews,” one aspect of the installation has captured news headlines around the world. I’m referring to the part where a Jewish man or woman sits in a Plexiglas container and answers questions from visitors. From 2 until 4 each afternoon, a member of the German Jewish community sits on a bench inside the case, a little sign displaying his or her name, birth place, and language. It’s the only information known to guests about the person aside from the fact of their Judaism.

Some immediately dubbed it the “Jew in the Box,” accusing the museum of portraying “the Jew” as if he were some sort of circus animal (or, like the aforementioned Hottentot Venus, a throwback to 19th-century European colonialist freak shows that displayed Africans in cages). Cilly Kugelmann, the museum’s program director, dismissed such characterizations when I spoke to her yesterday and described the container as a “vitrine,” a French word used to describe an elegant glass-paneled cabinet to display objets d’art.

I first visited the exhibition on Tuesday, primarily to check out the box—but when I got to the museum, I was equally intrigued by other displays. I encountered a German family inspecting a section framed around the question: “What do Jews do on Christmas?” The viral photograph of a message from the “Chinese Restaurant Association” thanking “the Jewish people” for “eat[ing] our food on Christmas” was on display. (The clumsily written sign actually appears to have been based on a cartoon David Mamet drew for Tablet back in 2010.) Meanwhile, a projector played a cartoon from Saturday Night Live, done in the mock-up style of a Burl Ives Christmas special. In it, 1960s-era African-American songstress Darlene Love belts out “Christmastime for the Jews,” singing about how Jews “really get the party going after dark, circumcising grateful squirrels in the city park,” among other hijinks. Laughing quietly to myself, I noticed that the joke seemed lost on the German family, which watched the video with blank expressions. Perhaps the exhibit—bringing a heavy dose of American-Jewish humor to a German audience—was more necessary than I imagined.

Still, I wanted to find out if sitting inside the box would make me feel like a caged monkey or like a Fabergé egg. I emailed the museum asking if I might be able to spend an hour in the display. (The museum has been receiving one or two emails per day from local Jews volunteering to sit in the box.) I got the go ahead and set up shop at lunchtime on Wednesday.

***

The “Jew in the Box” is actually just one of over 30 elements in the exhibit, which, inspired by the Jewish tradition of inquiry, is thematically composed of questions ranging from the mundane to the profound. Geometrically edgy, bright purple benches and display cases contain rare artifacts documenting Jewish life and the history of German Jews (one of the most impressive items in the exhibition’s collection is the original copy of the 1952 Luxembourg Agreement, establishing German responsibility for the Holocaust and signed by then-Chancellor Konrad Adenauer and Israeli President Moshe Sharett, which capstones the question, “Do Germany and Israel have a special relationship?”).

Some of the questions and associated displays are playful. For instance, the question “How can you recognize a Jew?” is accompanied by 70 items of Jewish headwear, ranging from kippot with Nike swooshes to a traditional wig worn by an Orthodox woman. Meanwhile, a German shepherd muzzle adorns the display case alongside the question, “Is a German allowed to criticize Israel?” illustrating the belief, widely held among Germans, that they run the risk of being called anti-Semitic if they dare say a critical word about the Jewish state. Yet to balance out that predominant view, the curators also post a brilliant text by German writer Philip Meinhold, who lists “10 Tips for an Israel Critic,” which include, “Cite one Jewish critic of Israel, because one who cites a Jew—as in the nature of things—cannot hate the Jews.”

“The Whole Truth” was inspired by a 1996 exhibit at New York’s Jewish Museum, “Too Jewish,” Kugelmann told me. That show featured items like a parody of Andy Warhol’s silkscreens of Jackie Onassis featuring the visage of Barbra Streisand, and an outfit from Jean-Paul Gaultier’s “Hasidic” collection,” in which female models adorned themselves with ersatz payes. Kugelmann said she considered bringing it to the Frankfurt Jewish Museum, where she worked at the time, but “no one would understand it. If you miss the punch line of the joke, the joke is finished.” (Indeed, it is a failure to appreciate German unfamiliarity with Jews and Judaism that colors so much of the vitriol being directed at Berlin’s Jewish Museum. Perhaps that explains the fact that the vast majority of those who have criticized the exhibition are Jewish.)

Kugelmann said she was determined to avoid the fate of most exhibitions staged by Jewish museums, particularly those in Germany, which wind up being “didactic exhibitions for a gentile public.” She believed having a Jew on hand to answer questions would spur conversations rather than shut them down.

So, at noon yesterday, I excitedly assumed my place in the vitrine. “Are there still Jews in Germany?” read the inscription below the Plexiglas box, my physical presence apparently serving as an answer. Kugelmann tells me her vision of this much-derided element of the exhibit is that is serves as a “Hyde Park Corner,” where guests can engage in conversation and argument with each other and the Jewish specimen on display. We “make a point of not answering questions,” she said.

My interlocutors, however, did not seem to understand this. One German man asked me if Jesus was Jewish, Christian, or both, and how a Jew could be the basis for the Christian religion. I gently explained that I was not a theologian. Another, more interesting and perplexing question, came from an elderly British gentleman, who asked, if Judaism is passed through the matrilineal line, does this not lend credence to the notion that Jews are a “race” and therefore provide fodder for Hitler’s dangerous theories? One can convert to Judaism, I explained, which negates the concept of “Jewish blood.” Moreover, while the Nuremberg laws did not distinguish between an observant, Orthodox Jew with just one Jewish grandparent and an atheist, non-identifying Jew with four, Jewishness is ultimately something that one must intrinsically feel, regardless of his family background. I have friends whose only Jewish parent is their father, I ventured, yet who nonetheless identify strongly as Jewish.

Everyone who approached me seemed intrigued, or at least tickled, by my sitting in the box. That is, except for the two Israeli women who said that my sitting there reminded them of Adolf Eichmann trapped in his glass witness box in a Jerusalem court room. Initially, I too shared their skepticism, I explained, but changed my mind after viewing the exhibit and sitting in the box.

To me, the “Jew in a Box” is an ironic, meta-commentary on what it is like to live as a Jew in contemporary Germany: You feel sometimes that you are an endangered species—or, as the museum commentary puts it, “a living exhibition object.” As a Jew in Germany, you are confronted by your Jewishness, your difference, on a continual basis, like the time I saw ads in the Berlin U-Bahn likening the practice of circumcision to child molestation “I have never felt so Jewish until I moved here,” I told the Israeli museum guests. The younger Israeli responded that “you only feel that when you let yourself feel like that.”

More often than not, I felt like a therapist for anxious Germans working through their fraught relationship to history. “This is very difficult for me,” a producer for a German television station said, standing just inches away, her eyes watery. “I feel it is a confrontation.” She likened the experience to a 2010 Museum of Modern Art exhibition by performance artist Marina Abramović, in which visitors sat silently across a table from Abramović for hours on end. Another middle-aged woman with her young daughter in tow related how the Jew she was closest to was her childhood piano teacher, whose Jewishness was only been hinted at through occasional references to family back in Israel. “I was a little ashamed to ask questions. It’s nice that you’re here,” she confided.

“If you want to ask somebody,” about their Judaism, “it’s like pointing,” she said. Many Germans have an understandable apprehension about discussing Jewish questions, an uneasiness that also stems from a general German reserve. “In New York, you ask questions,” she said. “What do you do? Where are you going? How much money do you make?” she said, moving her arms in exaggerated motions. “Here, you don’t.”

It wasn’t long before the roles were reversed, with me asking the questions. Growing up, I learned, she would “constantly touch fascist German history abroad.” Traveling to Amsterdam at the age of 17, she experienced a great deal of anti-German sentiment, a sense of “still open hostility,” even though she had been born long after the end of World War II. She is happy that her 23-year-old son can discuss all of these issues—Jews, Germany’s war history— “more openly than we would, and not with this petrifaction that used to strike us.”

These are not the types of conversations that I regularly have with Germans in the 10 months I have lived here—at least not random ones I’ve just met. And so if engaging in such a worthwhile dialogue required my serving as a living, breathing museum exhibition for one hour, then it was worth it.

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

James Kirchick, a visiting fellow at the Brookings Institution, is a columnist at Tablet magazine and the author of The End of Europe: Dictators, Demagogues and the Coming Dark Age. He is writing a history of gay Washington, D.C. His Twitter feed is @jkirchick.

James Kirchick is a Tablet columnist and the author of Secret City: The Hidden History of Gay Washington (Henry Holt, 2022). He tweets @jkirchick.