A Farewell Wave to ‘The Village Voice’

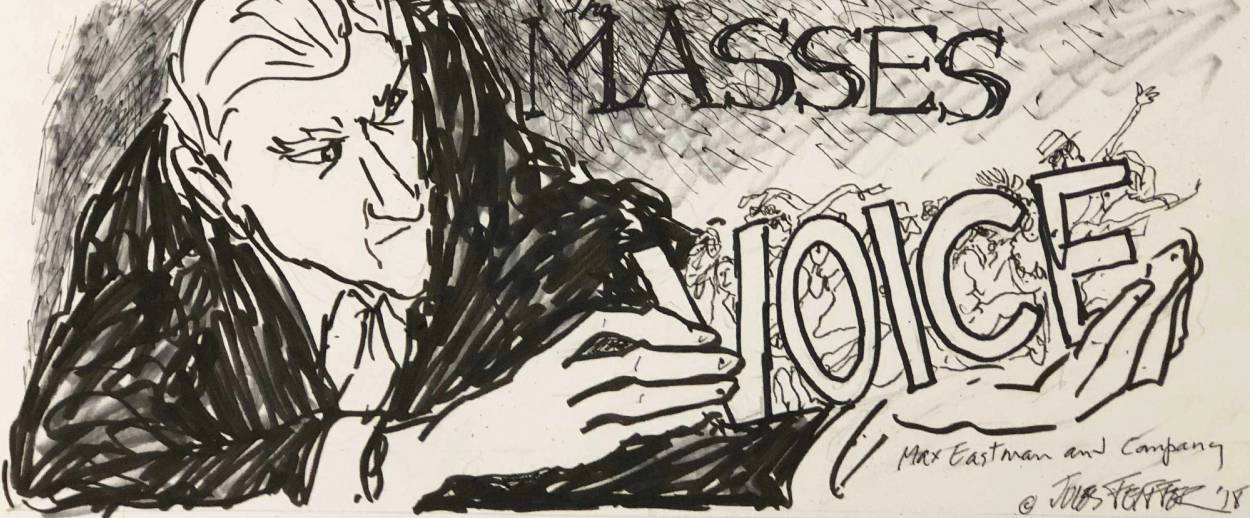

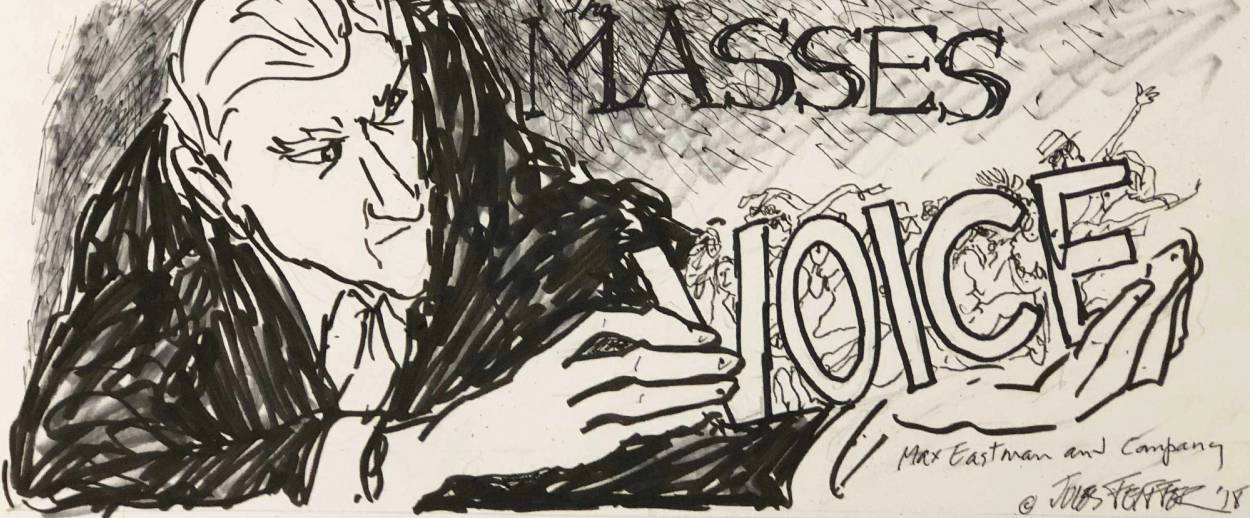

And a flashback to ‘The Masses’ of 1912, with special artwork by ‘Voice’ alum Jules Feiffer

The Village Voice officially expired a few weeks ago, and some part of me has been feeling a little homeless ever since in the Robert Frost sense, with home defined as the place where, when you have to go there, they have to take you in. I did use to think that someday, because the world is cruel, I might have to knock on the Voice’s door and ask them to take me in; and I always imagined or idly fantasized that, because the Voice was kind, they would do it. The Voice seemed to me kind because, back in 1978, I submitted a piece “over the transom,” as we used to say, without a commission or knowing anyone on the staff. And they published it, which was kindness itself. The piece was a modest book review. And the Voice came to feel like home because I spent the next 14 years writing additional such reviews, sometimes at extravagant length.

My essays made themselves at home in the Voice Literary Supplement, which was M Mark’s section, side by side with similar pieces by Walter Kendrick, the historian of pornography, and Geoffrey O’Brien and other luftmenschen of New York in the 1980s, the first generation of VLS regulars. I was appointed a third-string theater critic. One week I was the substitute restaurant critic. The editors dispatched me to Nicaragua to cover the Sandinista revolution and its troubles. They dispatched me to Eastern Europe to cover the revolutions of 1989. Timidly I broached the possibility of writing about fashion shows someday, though I knew nothing about fashion (but I argued: Mightn’t ignorance be an advantage? What if I wrote about fashion from a strictly subjective standpoint, the chronicle of a man who doesn’t know what hit him?). I wanted to spend two weeks as the alternative to Lynn Yaeger and Guy Trebay. The editors were tolerant. They were all-forgiving. There was no assignment, but no one laughed me out of the office. And, in the quarter century after I lowered my name from the masthead, which was in 1992, the half of my personality that will always regard The Village Voice as home somehow kept on generating still more oddball proposals for the imagined day when my return might prove to be necessary.

A few years ago, Stanley Crouch—whose voice on the page was distinctive even at the Voice—staged an event at Lincoln Center, and I ran into Robert Christgau, the rock critic and Crouch’s editor from the past, who was still at the paper. And I put the question to him. What if I were to return in a very specialized manner, this time as a music critic with a solitary focus, which would be the legacy of James Brown? The virtues of James Brown were an established theme at the Voice. Thulani Davis wrote one of her finest Voice pieces on the joys of dance parties with James Brown on the record player. R.J. Smith was one of the music critics during my period, and he went on to write a full-scale biography. My own proposal was for an extended series. Mr. B. himself was gone by then. But I proposed that, every time one of his sidemen, Fred Wesley or Maceo Parker, came to town, I review the performance, and glance back at old recordings, and maybe I would review the reviews, and, in that fashion, I would conduct a serialized inquiry into the inner mathematical essence of James Brown-ness.

Christgau has a gift for enthusiasm (it is the secret of his music criticism), and the mere prospect of such a series lit him up. He launched into a riff on the historic significance of James Brown’s rhythms, which had made him the single most influential pop musician of the last half century, given hip-hop and whatnot. I counter-riffed with thoughts of my own, not so admiring of hip-hop. The riffs and counter-riffs miraculously harmonized. They syncopated. Syncopation hit a backbeat. We were the J.B.’s. I came away thinking the job was mine, possibly. Only, a pity, the Voice had already entered its long descent into extinction, and, before I got back to him, the paper downsized one more time, and Robert Christgau himself, the dean of rock criticism, was out the door. The firing of Christgau was an unthinkable development. But then, no one ever imagined that someday The Village Voice as a whole was going to expire.

My original contribution—the piece that got me into the paper, back in 1978—was a review of a biography of Max Eastman, the editor of the Greenwich Village magazine The Masses in the 1910s. I am in no rush to dig up the review. I picture it as a plank of pine, knotty and stiff. I remember my intention in writing it, though. I was a Voice reader, and I thought the editors and writers displayed an insufficient knowledge of their own Greenwich Village roots; failed to recognize that cultural liveliness was compatible with philosophical depth; failed to distinguish between the good Marxism and the bad Marxism; failed to appreciate the light touch on heavy topics; and, all in all, stood in need of a useful and illuminating lecture on bohemian sophistication in its 1910s version. I was, in sum, perfect for the Voice. My every impulse was an obnoxious conceit. The piece went in the mail, and the book-review editor, who was Eliot Fremont-Smith, replied by telephone, inviting me to drop by the office to introduce myself. I was there the next day. Instantly I comprehended that, at The Village Voice, the editors knew very well the Village history, and were entirely reverent of bohemian days of yore, and did not need me or anyone else to tell them anything at all. Never was a newspaper more conscious of its own traditions and place in history. Fremont-Smith himself had developed a wild style of literary commentary at the Voice, consisting of a stream-of-consciousness spritz. He was a bop prosodist. A bed of solid learning lurked beneath the stream of words, however. And he published my naïve commentary on the great Eastman.

It is heartbreaking, really. Cultures thrive because the right people are in the right place. The editors of the Voice, during my time, were people who had appointed themselves to be in the right place, and consciously they made themselves the masters of the Village and its lore. It wasn’t just Fremont-Smith. The theater department—Erika Munk ran it during my period—was top heavy with the historical-minded, maybe because Erika herself and most of the other critics were champions of the avant-garde, and the entire notion of an avant-garde makes sense only if your eye is planted squarely on the past you wish to overcome. Sometimes Ross Wetzsteon was in charge. Ross ran the Obies, and he turned himself into a serious historian of the Village as a whole, and not just of its theater. His book, Republic of Dreams: Greenwich Village: The American Bohemia, 1910-1960, came out after he died. Ellen Willis produced columns and essays the way she did because she had in mind Partisan Review from long before, even if there had never been anyone precisely like her at Partisan Review. Jules Feiffer had his eye on The Masses itself. Nor were the politicos any different. Jack Newfield took pride in living in a house that used to be Paul Robeson’s.

It is always said that, in the glory days of Greenwich Village, the custom was to lament one’s own era as second-rate, and to suppose that bohemia’s Golden Age lay in the past; and that was certainly the custom at The Village Voice. Each new decade at the paper was said to represent a pitiful decline from the previous one. But that merely shows how seriously everyone took the history. Today I wonder how anything in the old tradition is going to survive, without a living-and-breathing institution to cultivate it on a weekly basis. The universities are going to be of limited help on this matter. Universities have their own traditions, but they cannot preside over the memory of an extended bohemian revolt against universities. Besides, New York University is a real-estate monster, and it disembowelled Greenwich Village many years ago. Someday a museum exhibition will celebrate the bohemia of the Village, and the objects on display will look like a dead butterfly collection, pinned to the page.

II.

I conclude that my choice of topic for my first piece was an inspired one, or else a lucky hit, maybe not in 1978, but from the standpoint of today. It is because of the demise of the Voice, which signifies the end of the Greenwich Village bohemia as a whole, which invites a question about the beginning. Namely, what was it, exactly, that gave rise to Greenwich Village, back in the beginning? The animating spirit, the energy, the founding inspiration—what were those things? And there is an obvious place to look for answers, which is in the life and works of the great Eastman.

By now there are two biographies of the man—the one that I reviewed, which was The Last Romantic: A Life of Max Eastman, by William L. O’Neill, and another that came out last year, Max Eastman: A Life, by Christoph Irmscher. I prefer the one by O’Neill. It is better on politics, if less good on personal matters. But there is, in any case, a still better account of the man and his life, which is the one by Eastman himself. It is his autobiography in two volumes, Enjoyment of Living and Love and Revolution, which, at a combined 1,200 pages, offer three times more information than can be found in the scholarly biographies, and 10 times more feeling and color, and 1,000,000 times more wit, and ought, in any case, to be regarded as a classic of American literature. And there, scattered among the chapters, you will stumble across Greenwich Village’s original inspiration, rendered visible for hundreds of pages at a time.

It was an inspiration from 19th-century America. Or rather, the inspiration was from the other 19th-century America, the one that hardly anybody remembers, which was atremble with social-reform and sexual-freedom experiments and philosophical originality and literary innovation. The Eastman family home was in upstate New York, and when Max was growing up there, which was in the 1880s and ’90s, the household seems to have absorbed and exuded every last avant-garde impulse and radical notion of the previous 50 years. Eastman’s mother and father were Congregationalist church people who worked as assistants to an ecclesiastical member of the Beecher clan of abolitionist renown—which is to say, they basked in the remembered sunlight of the grandest social-reform campaign of American history. Into the home came an influence from Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass and especially its sex poems, together with a cult of nudism, which somehow engendered a passion for feminism. Eastman’s beloved and brilliant sister, Crystal, grew up to become one of the pioneering leaders of the early-20th-century feminist movement. Mark Twain was a neighborhood presence. Eastman knew him as a child. Eastman’s mother, as a church minister, officiated at the funeral of Twain’s daughter. Eastman’s father, in his own capacity as church minister, officiated at the funeral of Twain himself. Eastman made his way to Columbia University, where he became a disciple and weekly dinner companion of the philosopher John Dewey, an old Whitman reader, who was the heir to everything that was daring and innovative about the American philosophy that descended from Ralph Waldo Emerson.

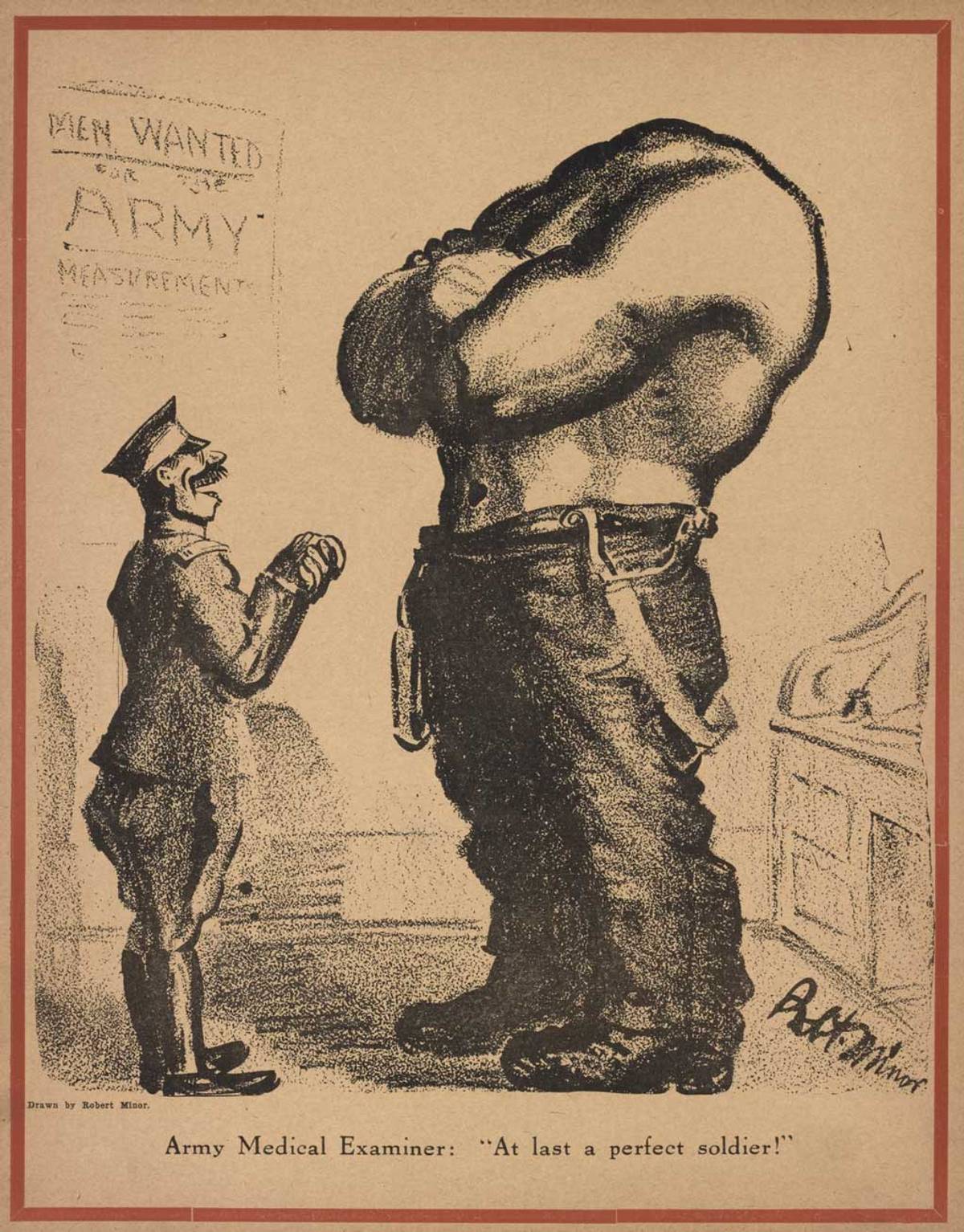

The Masses was a dour Socialist Party magazine in Greenwich Village, on the brink of folding. But, in 1912, Eastman, at age 29, took over as editor, and he poured into the magazine each of those marvelous influences from home and his revered professor––the earnest social reform (including an occasional invocation of Jesus, the socialist comrade), the sex radicalism, the free-verse spirit of artistic innovation, the philosophical pragmatism, and a genius for the prose rhythms that make for humor. And one other thing: the charcoal-line cartoons and drawings of John Sloan and George Bellows and a few other people from the Ashcan School. Oh, and another thing: Eastman’s wife in those years was a lively person named Ida Rauh, who helped found the Provincetown Players. And voilà: the new inspiration. It was the bright spirit of the 19th century, on its radical side, rendered electric, as if by Thomas Edison. The 19th-century brightness made a magazine. It made a way to live, with a neighborhood to accommodate the radical ideas, or maybe two neighborhoods, if you count Provincetown, which was everybody’s summer getaway—even if the Village itself had already begun to seem, in Eastman’s phrase, too “Greenwich Villagey” to bear.

The founding brightness, as it happened, was a fragile thing. In 1917, Woodrow Wilson led the United States into World War I, and the gloom of the 20th century settled in. Most of the intellectuals in the Socialist Party of America came out in favor of America’s participation in the war, and so did some of the editors of The Masses, e.g., George Bellows, the boxers’ portraitist. But Eastman himself and his closest comrades, who dominated the magazine, went the other way. They were militants of the anti-war cause. And the Wilson administration and the State of New York set out to jail the militants (which proved to be beyond the government’s power) and to crush the magazine (which proved to be entirely feasible). Eastman responded by founding a new magazine, The Liberator (with a name drawn from an abolitionist newspaper), which was pretty much The Masses, redux. Only, the mood was darker by then, and the emotions angrier, and the political radicalism went veering in perverse new directions.

One of Eastman’s writers from The Masses, the flashiest of them all, was John Reed, who made his way to Russia in time to observe the Bolshevik coup in St. Petersburg in October 1917. Reed worked up an excited report, breathless with enthusiasm for Bolshevism’s possibilities, and Eastman ran it in The Liberator under the immortal title, which was Reed’s, Ten Days That Shook the World. A variety of factions of the old American Socialist Party were beginning to put together a new Communist Party. Reed enlisted in one of the factions and returned to Russia to play his own part in the revolution and to write still more about it. Only, he succumbed to typhus. The Bolsheviks buried him in the Kremlin Wall. And Eastman stepped up to take his place. He, too, joined the Communist Party. He made his own way to Russia to see what was what. He was divorced by then, and he married a Russian woman with family connections to the Bolshevik elite. He learned Russian by translating poetry. He established a slightly vexed friendship with Trotsky. He translated Trotsky’s magisterial History of the Russian Revolution. And he stayed a couple of years, which meant that, when he began churning out a series of epilogues to Ten Days That Shook the World, his studies of Soviet affairs and the Communist movement, he drew on a degree of expertise that was significantly deeper than anyone else’s in America and the English-speaking world, apart from a handful of Russian emigrés and exiles who had ended up in the West. Expertise put him in a difficult spot, however. His reports on the Soviet experience turned out to be progressively more upset and condemnatory—until Stalin himself, outraged, declared that Max Eastman, the American, was a “gangster of the pen.”

But I do not mean to dwell over the story of Eastman’s battles during the next decades—only to observe that, in Enjoyment of Living and Love and Revolution, where you can read about these matters, you can also see the charm of the man. His prose is a marvel of sharp epigrammatical concision, derived in part (it seems to me) from Mark Twain, and in part (it seems to his biographer Irmscher, who appears to know Russian and must be right) from Trotsky, who commanded an epigrammatic concision of his own. It is a witty style in the particular vein that, having begun with Twain, advanced to Eastman himself, advanced yet again to Dwight Macdonald and maybe to Gore Vidal (on his good days) and I am not sure who else—a good-humored and sometimes humorous prose, amusingly ironic, superior, crystalline, languid, content with itself, always agreeable, and yet flexibly capable of recording the horrible and the tragic, whenever appropriate, which turned out to be all the time. Maybe there is a touch of the heroic, too, in Eastman’s prose, as befits a man who yielded not at all (apart from an occasional tactical maneuver) in his battle with Woodrow Wilson, the tyrant, and not at all in his battle with Stalin and the American Stalinists, and kept his aplomb all the while—except for a few years in the 1940s and early ’50s, when his enemies seem to have gotten under his skin.

I think Eastman’s prose is a main secret of Greenwich Village and its successes. It is fine and good to package together a group of earnest social reformers and innovative artists and the proponents of a gender-relations revolution, but if nobody has come up with a properly simple and charming and witty way of expressing the new ideas, sufficiently tapered to serve as a wick, the whole thing will never ignite. The Masses and The Liberator came up with a suitable way. And out of those magazines and their bright image and their friends came a long series of other journals, bohemian and anti-bourgeois, comprising the Village press over the years—beginning perhaps with Emma Goldman’s more wooden and sometimes alarming and sometimes marvelous Mother Earth, which was contemporaneous to The Masses; and advancing to New Masses (in its early days at the end of the 1920s); and Partisan Review for a period during the later ’30s, when Dwight Macdonald was writing for it; and Macdonald’s own magazine in the 1940s, the witty and radical Politics; and ultimately, beginning in 1955, the large-circulation Village Voice; together with the newsstand rivals to the Voice over the years, the down-market East Village Other, the sophisticated Soho News, and the New York Press; together with some of the strictly left-wing magazines, the anarchist Vanguard in the 1930s, the pacifist Liberation beginning in 1956, and still others, too. I suppose that, in principle, the Communist Party theoretical journal, Political Affairs, ought likewise to be counted as an heir to Eastman’s magazines, given that, when he set out for the Soviet Union in 1922, he considered himself a Communist and turned over his Liberator to his fellow Communists, who converted it into their own Workers’ Monthly, which became Political Affairs, which still exists online. But the tradition that I am describing was never a Marxist tradition. Nor was it the respectable tradition of The Nation or Harper’s, even if The Nation and Harper’s happen to have their offices downtown.

The tradition was anti-respectable, or, at least, arespectable. It was the Village tradition, and nothing else. Not everything about that particular tradition was wonderful, but the durability was undeniable, such that, having come into life in 1912, it managed to linger into our own moment, shriveled and decayed and, even so, recognizable. And only now, at age 106, has the long tradition definitively exited from the downtown streets, wheeled away on a gurney. The exit is a big event. At least, in my eyes it is. It is something that was never supposed to happen. I feel like Eastman’s father, presiding over the funeral of Mark Twain. Was Eastman père astonished to see that someone who wrote so wittily needed a burial? Me, I am astonished at the disappearance of The Village Voice.

***

For sketches of Village Voice writers, I refer the readers to this, on Nat Hentoff, and this, on Alexander Cockburn (with additional remarks on Jack Newfield).

Paul Berman is Tablet’s critic-at-large. He is the author of A Tale of Two Utopias, Terror and Liberalism, Power and the Idealists, and The Flight of the Intellectuals.