Simple Videos and Complex Causes

The meaning of the shocking, horrifying, and revelatory recording of George Floyd’s death

Before anyone gets too involved in pondering the deeper and hidden causes of the insurrection, e.g., the class structure of the protest centers, the urban-rural split, the flow of capital, the peculiarities of a new generation, the mysterious dialectic between protest and crime, etc., it might be useful to dwell for a moment on the cause that is not at all hidden. The immediate cause. This was the Minneapolis video. It explains pretty much everything.

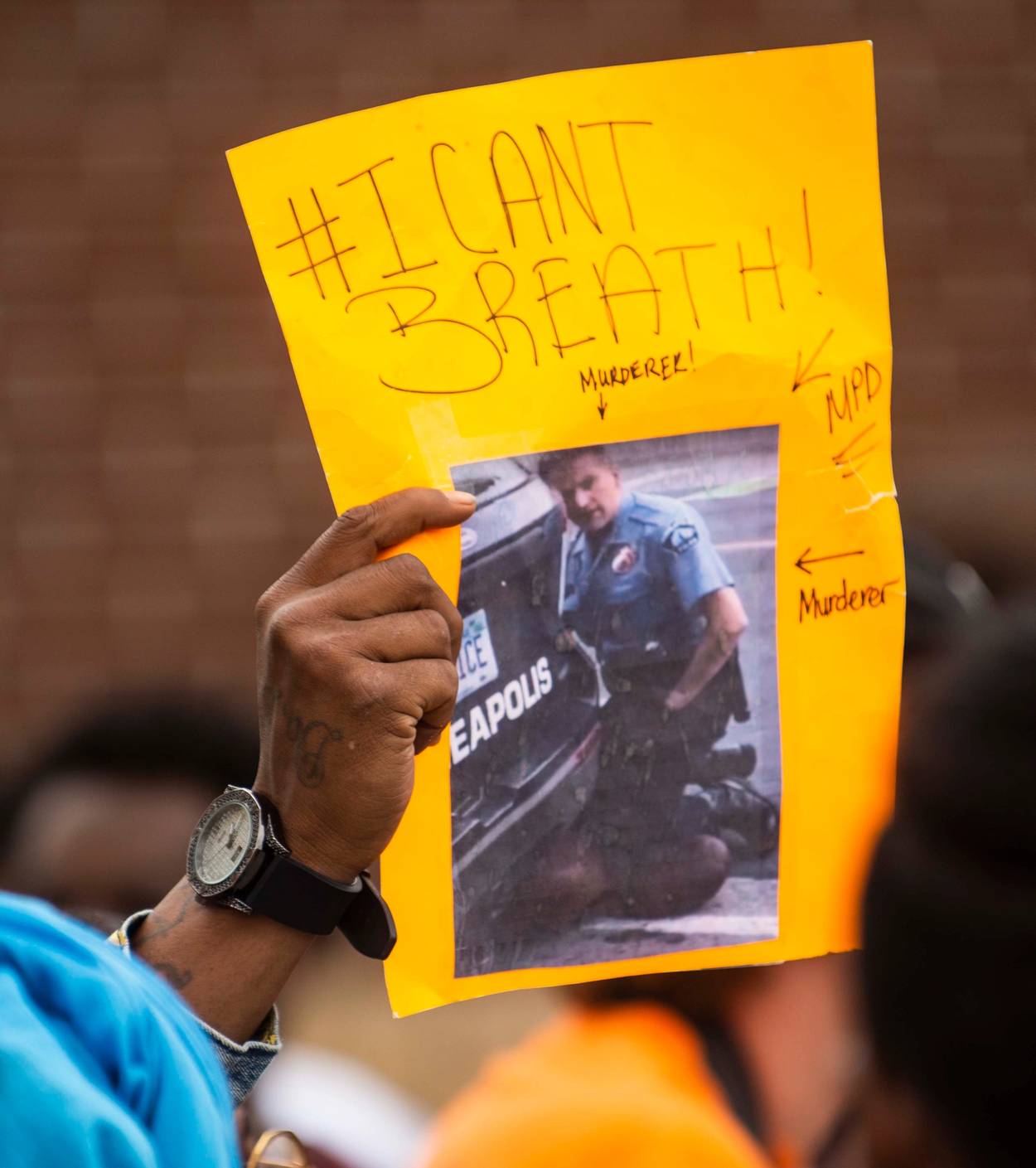

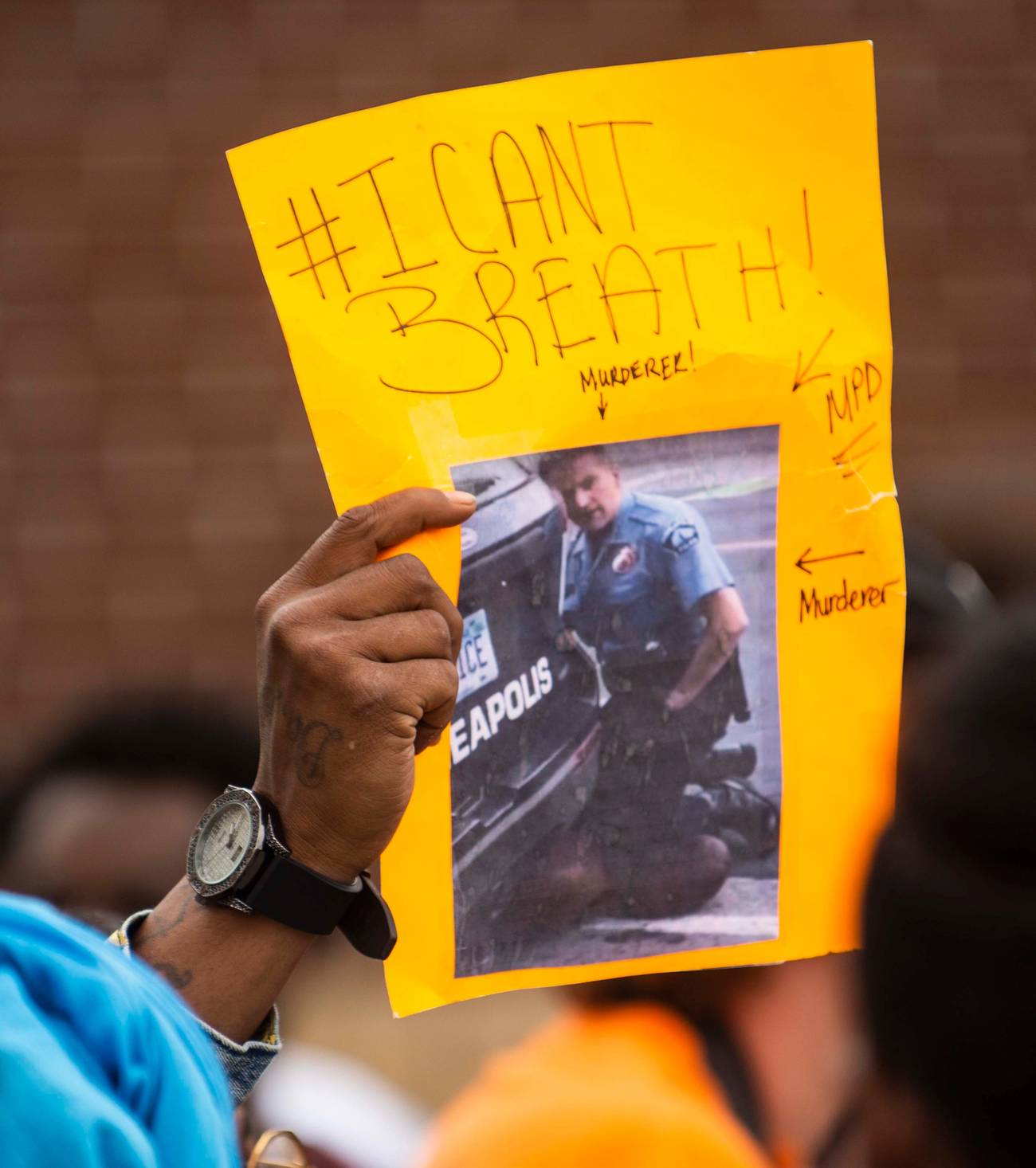

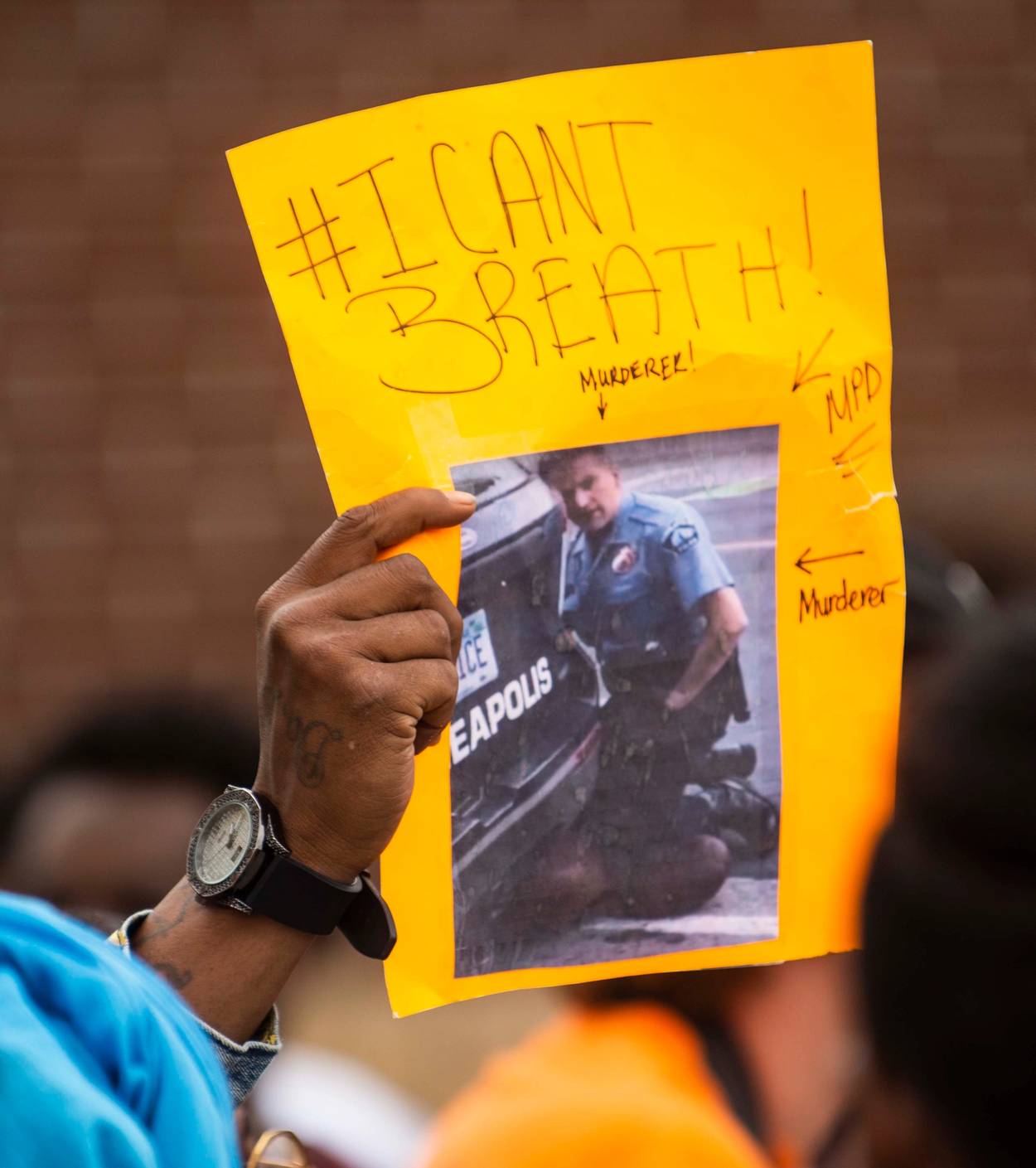

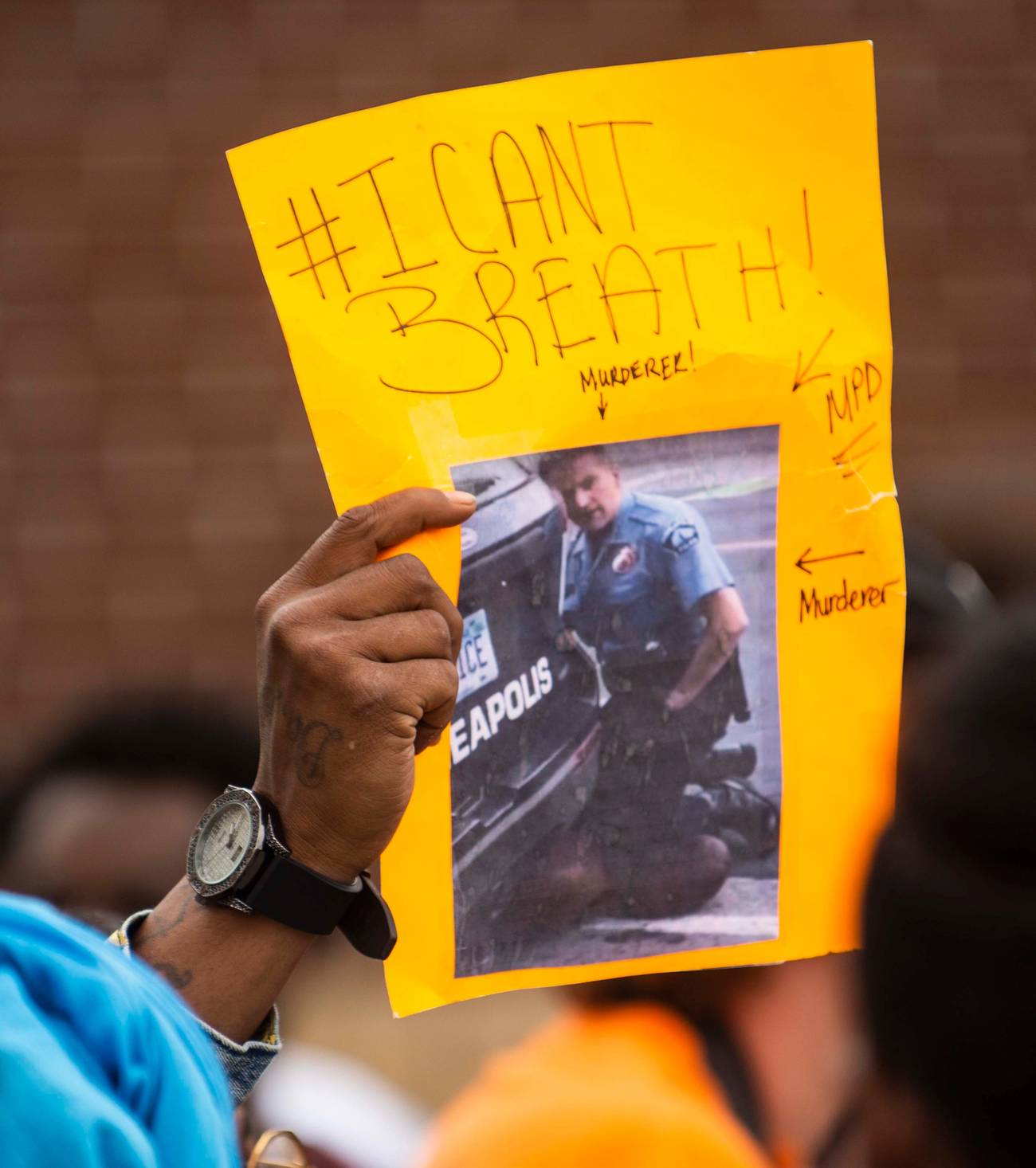

The video has three aspects, emotionally speaking, which are, in progressive order, shocking, horrifying, and revelatory. It is shocking to see George Floyd begging for his life, and then ceasing to beg. It is horrifying to see how confidently Derek Chauvin, the experienced cop, plants his knee on Floyd’s neck. But it is revelatory to see the other three policemen. Those other men seem not the slightest bit agitated. This aspect of the video requires a moment’s reflection on the part of the viewer. But the meaning does sink in.

The three policemen, by participating calmly, make it obvious that, in their eyes, Officer Chauvin is merely, like them, a cop on the job. Chauvin is not a madman, or a man who has been driven into murderous folly by frightening events. Nor has Chauvin fallen victim to the confusion of combat, like a soldier who, under the stress of military action, ends up shooting in the wrong direction. Chauvin is not even an individual. On the contrary, he is part of a unit, he and the other three. The four of them maintain their discipline. And this, to anyone watching the video—to me, at least—is the revelatory aspect.

The argument over atrocious police violence against blacks, or against anyone, has always turned on a choice between possible interpretations—the interpretation that regards atrocious violence as the work of irresponsible individuals, without institutional significance; or the interpretation that regards atrocious violence as the product, instead, of a larger malign culture, with definite institutional implications; or the interpretation that regards atrocious violence as a legitimate response by the police to criminal behavior, and not as anything atrocious at all, even if people sometimes do go too far. Naturally, a video from the streets of Minneapolis is not going to settle this argument. But no one can doubt that scenes from the video tilt sharply in the direction of interpretation number two—the interpretation that speaks of a larger and malign culture, with institutional implications.

The four officers have the look, after all, of a unit that believes itself to be correctly operating by the book, without the slightest embarrassment. Only, how can they believe such a thing? The obvious explanation is that life in the Minneapolis Police Department has led them to believe it. They do not look like rule-breaking rogues because they are not, in fact, rule-breaking rogues. They may be going against the advice proffered by their reform-minded department chief and their hapless mayor.

But they are conforming to the real-life standards of their fellow officers, which are the standards upheld by the police unions, which are, in turn, the standards upheld by certain kinds of very popular politicians. “Please don’t be too nice,” said the president of the United States to the police officers of Long Island in July 2017, with specific advice to take people under arrest and bang their heads as they are put into police vehicles. Why, then, should the four cops in Minneapolis consider themselves rogues? That is the revelation. The four cops consider themselves the enemies of crime, as they go about committing their crime. And the spectacle of them doing so casts the most dreadful of lights over the entire profession, not because the profession lacks better people, but because the better people do not set the tone.

We see it in the other horrendous video that has lately emerged—the one from Buffalo, showing the police knocking Martin Gugino, the gangly and voluble protester, to the ground, where he lies as if dead, blood pouring from his ear. The video in this instance does not speak to questions of racist hatred, given that Gugino is white. And Gugino has not died. He may well have appeared somewhat threatening to the police, having walked up to them with too much determination and too frisky a right hand. The scene is atrocious, even so. If they did not like what he was doing, they could have arrested him. But the revelatory thing is what happens next. A single cop bends down to see how Gugino is doing—and is right away ordered to stand up and keep walking forward, together with a large number of other cops. And the whole lot of them march on by, the one momentarily decent cop and all of the rest of them, triumphantly indifferent to the bleeding body stretched across the pavement.

It is shameful. It is Minneapolis-like. And if the meaning of the Buffalo scene has needed any confirmation of its own, the police department of Buffalo has provided it. The mayor responded by doing the obvious thing, which was to suspend the two cops who so pointlessly knocked Gugino down. And 57 officers, encouraged by their union, resigned from their emergency police committee in protest of the terrible thing that had been done—not to Gugino, but to the two uniformed brutes who wronged Gugino.

An institutional problem, then, which is fundamentally a cultural problem. But how can it be that, after so many years of earnest discussion of racial hatreds and police work, these problems persist? I cannot understand it—and yet, I do see that my question is fairly stupid. The problems persist because a vast public does not agree in describing any of this as a problem. Institutional racist violence persists, and likewise a nonracist institutional violence, because enormous numbers of people are in favor of the billy club and the chokehold. The enormous numbers feel confident in their assumptions, too, and are fortified in their confidence by the highest authority in the land, no less. Nor are a couple of videos going to change their minds. It is appalling, then. It is enraging. It is also more than enough, all by itself, to ignite a (mostly) refreshing revolt, massive, persistent, and historic.

Paul Berman is Tablet’s critic-at-large. He is the author of A Tale of Two Utopias, Terror and Liberalism, Power and the Idealists, and The Flight of the Intellectuals.