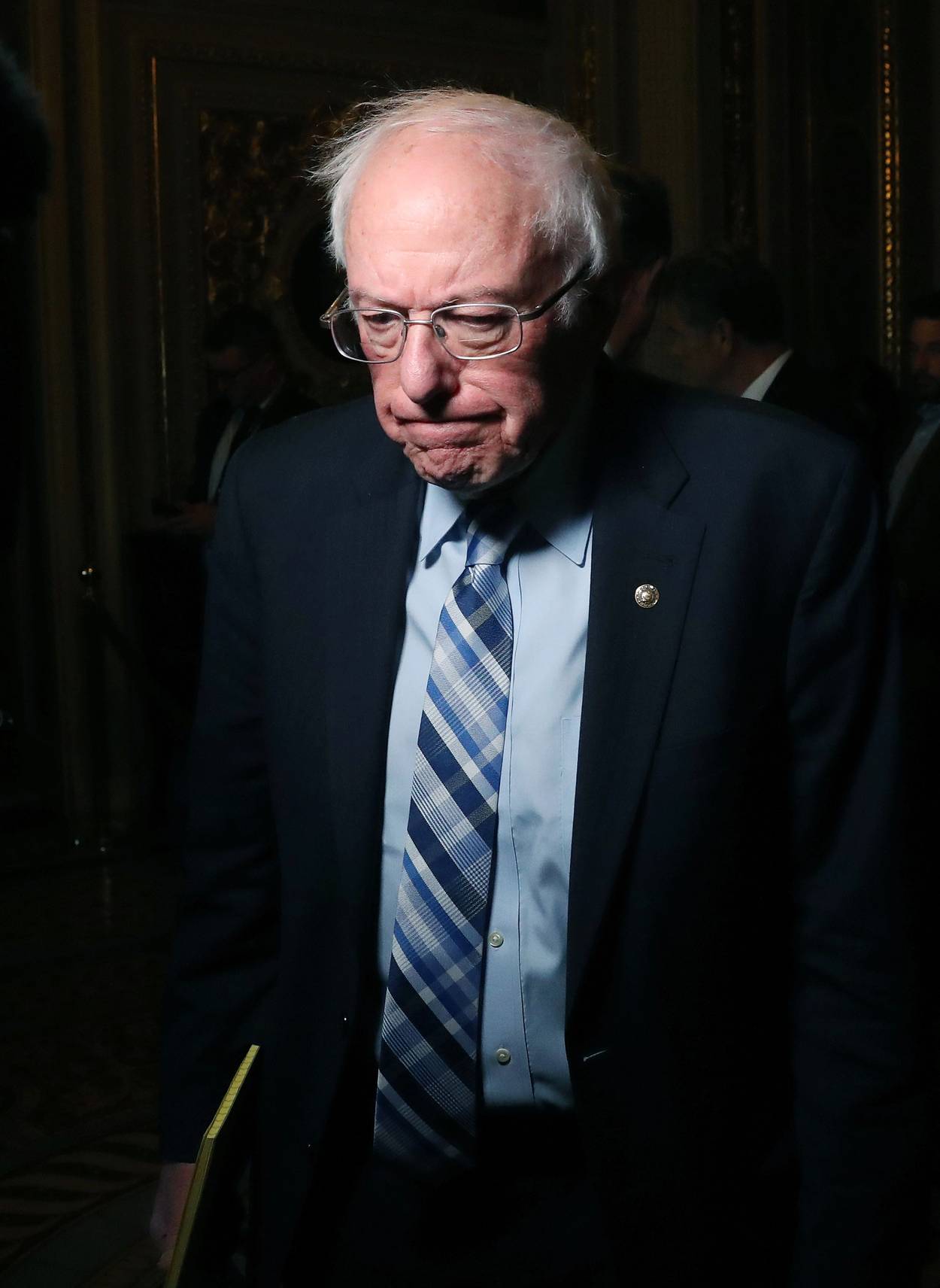

Did Bernie Sanders Fail to Seize His Moment?

The senator joined with the openly corrupt operatives of the Democratic Party instead of starting a pro-worker New Deal party that could have united an American majority

Over the past few months, Bernie Sanders has stood on the precipice of possibly the greatest accomplishment in all American leftist history. The Jewish kid from Flatbush, Brooklyn, who at various points had to live on unemployment benefits—and moved to Vermont to start all over—was on the verge of successfully navigating the labyrinthine halls of American governmental power and doing the impossible: fighting off the market fundamentalist capture within America’s state just long enough to enact the true social democratic reforms that have been locked in a freezer since George McGovern’s epic loss in 1972. Those moments of hope, though, have all but faded into the sewer of the Democratic Party’s open and systemic corruption, which has reached levels that haven’t been seen in American politics since the days of the Teapot Dome scandal.

The so-called infrastructure package Sanders developed for Biden was for real. In its recent $3.5 trillion form, the Sanders-designed bill would have created major child support payments, established paid family leave like the rest of the industrialized world, and provided free universal preschool and two years of community college. If enacted, it would achieve the greatest expansion of U.S. social safety nets since Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal—moving the country out of the laughingstock category (when it comes to social safety nets, at least) and toward some notion of a true compact among the American people.

But by the time this is published, the promise of the Sanders-designed “soft” infrastructure bill will likely have evaporated. A sad state of affairs for writers like myself, who would like to see the country build better social safety nets, protect the right to collectively bargain, and move toward living wages for all. And worst of all: It didn’t have to be this way.

Three years ago, Sen. Sanders faced an existential dilemma that flew under the radar of nearly every readily available media outlet. In 2016, to everyone’s surprise—including his own—Bernie’s insurgent campaign nearly derailed the Wall Street and establishment media-backed Clinton juggernaut. Instead of running for the Democratic nomination again, Sanders could have capitalized on the legion of followers he gained and started his own party—as some of his former surrogates begged him to do. Sanders, though, believed he could overcome all the earlier hurdles the next time around. This second time, there would be no Hillary. His campaign had overcome bad press before. They could do it again, Sanders figured. Sanders was poised to destroy the virtue-signaling cover that Democratic Party apparatchiks and hangers-on use to make themselves look good while doing evil.

Of course, things didn’t go according to plan. With four years to prepare, the establishment had a break-glass-in-case-of-emergency plan at ready.

At the time, Chris Matthews was pilloried on social media for his metaphor comparing the “battle” against Sanders’ supporters to Hitler’s army. What observers and critics missed in Matthews’ exasperation was that he was not speaking to the average American. At this point, MSNBC, CNN, The New York Times, and The Washington Post are mostly entertainment for wealthy elites and metro-area squares. Matthews was speaking directly to “tastemakers” and “power players” like himself. Do Democratic moderates want Bernie Sanders to take over the Democratic Party in perpetuity? Matthews asked, knowing the answer. Distress beacons were lit, signaling to all known Democratic Party allies far and wide: Unify. Biden’s a goofball but he won South Carolina. He’s a household name. We trust the guy. It’s him.

Sanders clearly made the wrong choice giving the Democratic Party a second chance. Had he ventured off on his own, he could have explicitly rejected woke dogmas—like the kabuki theater of “entertaining the notion” of reparations for 19th-century Southern slavery—and focused entirely on broad-based policies to rebuild labor protections, social safety nets, and his (former) points of agreement on trade and immigration policy with Trumpers. If he also had the wherewithal to return to the independent roots that got him elected in Vermont—where he rejected gun control and supported major restrictions on immigration—something interesting might have transpired.

I’m not sure what it is exactly that Sanders lacks—intellectual rigor? backbone? foresight?—but it should have dawned on him sometime in the five decades between 1968 and 2020 that the notion of a “left” as a meaningful concept had died during his youth. In the spring of 1968, when Martin Luther King was assassinated and Althusser no-showed for the Paris revolts a month later, the trauma was too much for anyone with integrity to fully recover from. While the true ’60s radicals licked their wounds, artist wannabes—with nothing but contempt for the working class—wormed their way into control of the boomer-era leftist institutions, eventually turning many of the West’s left-wing parties and universities into a demented group therapy session writ large.

The American “left” has existed in a zombified, self-parodic form ever since McGovern’s monumental defeat. Like a Marvel What If comic, the Democrats and their followers faced a historic turning point—they could come down off their high horse and realize that, just as he claimed, Nixon had indeed ridden a “silent majority” to victory. However, despite many pretensions to the contrary, the American working class, had not rejected the New Deal in any way. Prior to Watergate, Nixon was an immensely popular president, and, in many instances, he didn’t just support New Deal-style social safety nets, he was willing to extend them. During an economic downturn, Nixon enacted wage and price controls—and proposed a plan that required employers to buy private health insurance for their employees (which the Democrats rejected). He also initiated the detente with China that eventually led to the end of the Cold War. Instead of learning that they could reach working-class Americans the same way Nixon and Roosevelt had—by protecting their economic interests and shutting up about everything else—the boomer left instead became even smugger, socially elitist, and culturally anti-traditionalist.

The young boomer left’s hatred of Nixon began a long tradition of resentment toward right-wing leaders, including those who supported the New Deal and unions. Focusing almost exclusively on social issues—“fighting” racism, pro-lifers, and sexism—defined the Democrats’ post-McGovern era. A hollow “socially liberal” but “fiscally conservative” aura started floating around American letters in the late ’70s and ’80s, eventually taking human form as William Jefferson Clinton. Rather than appreciating the tenuous miracle of the New Deal coalition, America’s new left went about further alienating Democrats’ working-class base—leaning hard into social radicalism and away from economic populism. For this new left, expensive college degrees—and the cultural reprogramming one receives while getting one—became their answer for every social ill. The result has been a takeover of the mainstream press and both major political parties to the point where neither the economic interests of the majority, nor their social values, are given any hearing.

Over the last nine months, the U.S. has experienced the greatest wave of labor unrest since at least the 1970s and yet our supposedly “left-wing” media operations—again, like The New York Times, Washington Post, MSNBC, CNN, and most local newspapers—refuse to even acknowledge it. Long ago, these outlets axed their labor reporters for more “culture” coverage. Just as with The Wall Street Journal, in nearly every instance, our supposedly left news outlets frame their coverage in a manner sympathetic to management over labor. After Clinton helped deregulate the news media industry in 1996, even the country’s small local newspapers answered to billionaire overseers—which helps explain why so many editorials and syndicated op-eds agree with Matthews that Sanders’ attempt to merely bring American political economy in line with the rest of the industrialized world represents “Nazi-like” terror. The threat to management’s interests was genuine.

For a nearly three-year stretch after 2016, Sanders remained as the most popular politician in the United States. Consistent with the post-McGovern dispensation, though, cultural tastemakers then set a trap—convincing Sanders he needed to embrace woke social values to truly lead his revolt of the youth. However, just as with the McGovern campaign itself, younger American voters have never been reliable. Sanders fell into the woke trap, lost the Rust Belt, and then agreed to a role as Biden’s bag man—designing programs for a president, like Clinton and Obama, more interested in being liked by the metro-area commentariat than in any prolonged battles with corporate lobbyists and their congressional toadies. Decades into this mess, there is now a Ford F150-size hole in the “marketplace” of American politics.

Individually, each of the proposed social safety net policies of the Sanders-designed $3.5 trillion “soft” infrastructure bill is tremendously popular—which is precisely why holdouts Krysten Sinema and Joe Manchin never specify exactly what they are against. The price tag is too big, they say, never following up with what social programs they deem unworthy. If the Sinema experience proves anything, it’s that identity politics will be used as cover for all corporate excess until a groundswell inside the Democratic Party demands otherwise, or a third party overtakes their base. The “sex-positive,” “nonbinary,” “light-skinned Latinx” with Crayola-colored hair remains the spirit animal of establishment Democrats and the metro-area media. While performance art as politics has worn thin everywhere but Twitter and the graduate school classroom, Sinema’s blue-haired wigs and justice studies Ph.D. managed to endear her to enough of the Scottsdale crowd and Democratic donors to win her a place in the most exclusive club in the world.

There’s tremendous opportunity within the American political system for a pro-labor, anti-woke third party that isn’t strictly a home for bourgeois moralizing, word mongering, and victimhood peddling. A literal majority of Americans no longer identify with either major party, if not actively hold them both in contempt. One hundred million Americans—43% of those eligible—do not vote, most because they are too disgusted with the options on offer. If there is a consistent working-class base remaining in the Democratic Party, it’s on life support. Whether they’re able to fully articulate it, the plurality of the American public yearns for a return of the Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal coalition—a pairing of greater social safety nets and workplace security with social politics that respect them enough not to claim a new form of racial segregation is needed—but this time its “anti-racist”—or, similarly, that hormone blockers for preteen children are not only harmless, but desperately needed.

The list of social “truths” held to throughout today’s mainstream Democratic Party rejected by most Americans could go on for hours. Few Americans identify as “liberal,” much less anything resembling woke—and the numbers are even lower among ethnic minorities. Most Americans want Robert Reich–style economics without Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez’s outrage alerts and second-year grad student posturing.

Which means that the Democratic Party is no longer salvageable. Today’s Democratic Party is literally the party of people who think it is acceptable for employers to fire people for saying “offensive” things outside of work. Rather than pro-worker, they’re the party of tattle-tale hall monitors seeking gold stars for relaying what fellow employees say in the break room.

The Democrats’ transition from the party of labor to the party of upper and middle management hasn’t fully sunk in for Sanders. When the dust settles on Biden’s first two years in office, it will. Then, the devastation of Sanders’ 2020 mistake will be made plain. Proponents of labor rights and better social safety nets have to decouple them from woke politics, or they’ve lost the battle before it even begins.

In 2016, Sanders polled amazingly well with Republicans and independents. Even though he lost the nomination, by the end of his first presidential run, Sanders had the simple message of “taking the country back from the billionaires” that reached across both the left and the right. But with the establishment unified against him, and following his disastrous Super Tuesday showing, Sanders quickly packed up his 2020 campaign and all but conceded within a matter of days. Despite all the pomp and circumstance built up around the notion of him leading some “second American revolution,” in the end, Sanders opted for a tactic worthy less of Karl Marx and more his rival, Ferdinand Lassalle—who used to dine with Otto von Bismarck (to Marx’s great ire). In conceding the second time around, Sanders extracted key concessions from the future Biden administration, wrestling away a place as Senate Budget chairman; a coveted post, to say the least.

In the end, Sanders did what Eugene Debs, Henry Wallace, and Ralph Nader before him never could. He changed horses midstream, transitioning from barnstorming outsider to legislative architect and the leader of his own “squad” in Congress.

If the current reconciliation bill eventually passes, after being trampled on by Democratic Party-affiliated lobbyists, Sanders’ choice to play nice will have been validated on a historical scale. More likely, his decision to give the Democratic Party a second chance—and stand by his “good friend Joe”—will leave his supporters, and scholars of American political culture, debating what might have been.

B. Duncan Moench is Tablet’s social critic at large, a Research Fellow at Heterodox Academy’s Segal Center for Academic Pluralism, and a contributing writer at County Highway.