Betty Friedan and SCUM

In the first of four excerpts from Phyllis Chesler’s ‘A Politically Incorrect Feminist,’ the unholy feminist civil wars

It’s impossible to convey how excited I was—how excited we all were. While at work at the Brain Research Labs, I somehow heard about a women’s meeting. I rushed out, still wearing my white lab coat. I was on the streets searching for “the women,” as if a group of aliens had suddenly landed on Earth.

We were all lost in a dream—but we had never been so awake. Women who were once invisible to each other were now the only visible creatures. Women—who used to see one another as wicked stepsisters—had magically transformed into fairy godmothers.

Some of us smoked and drank, wore motorcycle boots, tough leather jackets, and no makeup; we were rather butch, whether we were straight or not. Suddenly we were the ones who made things happen, not those to whom things happened.

Some of us wore feathers, jewelry, soft suede vests, bell bottoms, and lots of makeup. We looked like gypsies or glamorous pirates, and we too made stuff happen. You didn’t mess with us anymore.

I was as foolish as only a young dreamer could be. I—but I was no longer alone; now there was a we—and we wanted to end the subjugation of women—now! We, who had put up with it from the moment we were born, wanted it to end immediately—or definitely within the decade. None of us understood that this work would occupy us for the rest of our lives and that all we would be able to claim was the struggle, not the victory.

Looking over my early feminist correspondence reminded me of how much affection we had for each other. We, to whom men had not listened, now found that our ideas mattered a great deal: to ourselves, to each other, to countless other women.

Oh, the number of feminists who signed their letters to me “With love”! As did I. We hugged and kissed each other as if we were relatives or longtime friends. But we were really strangers, bound only by the moment and our shared vision.

I am writing about heroic historical figures. What defines them is the work they did, not their fearful, mortal failings. Most women have internalized sexist values—but they don’t lead movements that change the world. However, from a psychological point of view, women—and feminists are mainly women—are as great a challenge to our liberation as men are.

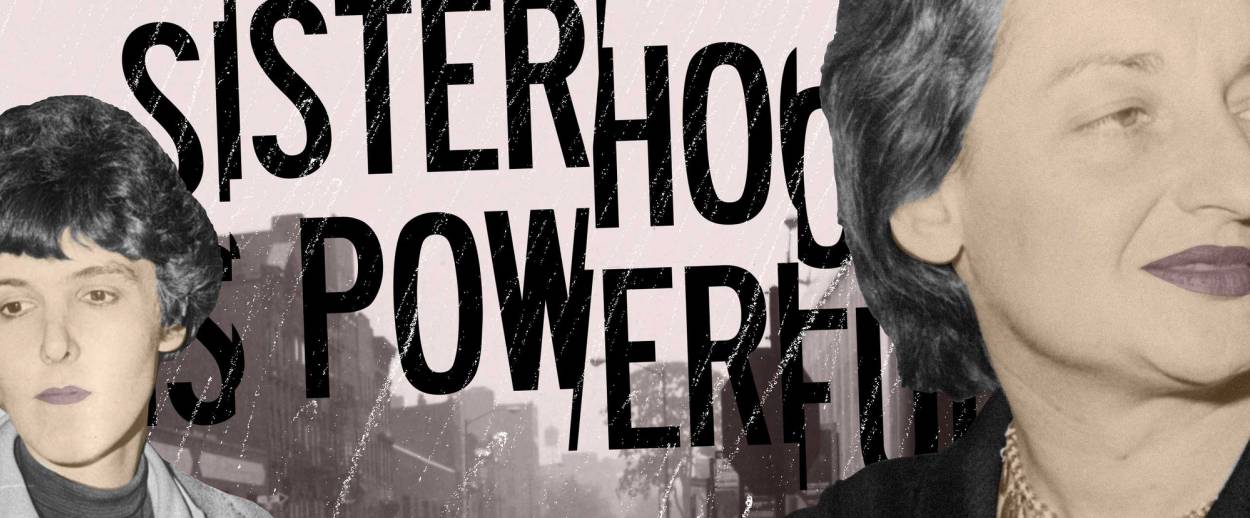

For example, we proclaimed that “sisterhood is powerful”—it’s such a lovely idea—but such a sisterhood did not normally exist; it had to be created day by day. Women did not always treat each other kindly. Somehow we expected feminists, who are also women, to behave in radically different ways. We were shocked as we learned, one by one, that feminists didn’t even always treat each other with respect or compassion.

I know this now. I did not know it in 1967.

We said that women were more compassionate and less aggressive than men, but this isn’t true.

We second-wavers took our battles seriously and fought with strength and conviction. We fought about essentialism versus social construction; reform versus revolution; Marxism versus capitalism; pornography versus censorship; prostitution versus a woman’s right to “choose to be a sex worker”; focusing only on abortion versus motherhood; viewing women as innocent victims versus viewing women as having agency and responsibility for what happens to them; and about whether a woman can be a real feminist if she sleeps with the enemy—men.

***

Like most women, feminists engaged in smear and ostracism campaigns against any woman with whom they disagreed, whom they envied, or who was different in some way. Unlike men, most women were not psychologically prepared for such intense and overt battles and experienced them personally, not politically—and sometimes as near-death experiences.

This didn’t drive most of us away; failing to acknowledge this phenomenon often did.

We now understand that all women, both white and of color, have internalized racial prejudice, but we fail to comprehend that women are also sexists and that, like racism or homophobia, we have to consciously resist this on a daily basis in order to hold our own against it; and that we will never be able to overcome it completely.

Once upon a time, long ago, I believed that all women were kind, caring, maternal, valiant, and noble under siege, and that all men were their oppressors. As everyone but a handful of idealistic feminists knew, this was not true. Living my life has helped me to understand that, like men, women are human beings, as close to the apes as to the angels, capable of both cruelty and compassion, envy and generosity, competition and cooperation.

Seemingly contradictory things can be true psychologically. Women mainly compete against and envy and sabotage other women, and women mainly rely upon other women for intimate relationships.

In 1980, when I began researching what would become my 10th book, Woman’s Inhumanity to Woman, many feminist leaders told me that I should cease and desist, that “the men” would use it against us. Years later I was talking to Shulie Firestone, and she said, “Phyllis, if only you had written Woman’s Inhumanity to Woman long ago, it might have saved our movement.”

“Shulie, I doubt that any book could have done that—but how kind of you to say so,” I replied. “Do you know how strongly feminist leaders and their followers opposed my writing this book? Their disapproval probably stayed my hand for years.”

“But why did you listen to them?” She was a bit agitated. I hugged her.

Psychologically, we second-wavers had no feminist foremothers and no biological mothers. We had only sisters.

If only we had known something—anything—about women’s history, specifically about our feminist foremothers, we might have been better prepared for the unholy feminist civil wars in which we often took no prisoners and never spoke to each other again.

If only we had known that suffragists had also fought hard and dirty and that politicians and ideologues behave this way, we might not have taken it all so personally.

If only we had understood more about the dark side of female psychology, we might have been able to find ways to resist our own mean-girl treachery.

If only.

Only now, a half century later, do I understand that women in groups tend to demand uniformity, conformity, shoulder-to-shoulder nonhierarchical sisterhood—one in which no one is more rewarded than anyone else. Marxism and female psychology are a natural fit psychologically, but not for me.

People say, “Women are their own worst enemies.” I cringe when I hear this. It’s not always true. Sometimes we save each other; most women could not live for more than a day without intimate female relationships.

In the beginning we delighted in each other; we wrote about our friends in published works of poetry and self-published mimeo handouts as if these women were already historic or mythic figures. Marge Piercy, by 1969 already the author of one novel and two books of poetry, and Martha Shelley, a poet with a growing reputation who was also an amazing lesbian feminist activist, both wrote poems to me. To be admired by women of ideas, by serious and talented women, is indeed wondrous.

Betty Friedan and others had founded the National Organization for Women (NOW) in 1966. As soon as I learned that a chapter had opened in New York City, I joined and signed up for the first committee I was offered: childcare. Heading it, most improbably, was radical feminist Ti-Grace Atkinson. Ti-Grace was close to Flo Kennedy, an African-American lawyer and Mistress of the Quick Quip. Flo-of-the-snappy-comeback affectionately called me various nicknames. Later, Flo and Gloria Steinem delivered lectures together.

Ti-Grace was a tall, willowy blonde who lived on East 79th Street. A large photo dominated the wall behind her living room couch: Ti-Grace as a bride, which she had slashed diagonally. Right there, in her apartment, I stood up and delivered a full-blown, fiery feminist speech; I said things I didn’t know I knew. We were no longer ordinary; we were all superheroes.

I attended meetings of the National Organization for Women. That’s where I first met Kate Millett. Kate wore her hair in a sleek bun, sported large dark-framed intellectual glasses, and spoke with a slight British accent—just to make sure you knew that she’d been to Oxford. She was a bit timid, pseudo-humble, and rather charming. She was married—her husband was a soft-spoken Japanese artist named Fumio Yoshimura.

***

Valerie Solanas’ self-published 1967 SCUM Manifesto is an angry, frightening, kick-ass feminist work. It’s daring and brilliant, a clarion call to arms, perhaps satiric, probably literal; she urges women to “overthrow the government, eliminate the money system, and eliminate the male sex.” Her manifesto is crazy.

Solanas was a physically abused child and incest victim who became homeless at 15; she was a lesbian, a panhandler, and a prostitute. Solanas gave birth to a child when she was 17; the child was taken from her.

Solanas’ life history resembles that of Aileen Wuornos, the woman who became known as the “first female serial killer” and the “hitchhiking prostitute.”

Both Solanas and Wuornos (in whose case I eventually became involved) became cult figures à la Jesse James. They were outlaws, but they were female outlaws, far beyond the cinematic Thelma and Louise. They attracted many straight and lesbian feminist supporters whose creative works—films, plays, books, songs, an opera—portrayed them. Solanas’ book was translated into more than a dozen languages. Academics wrote about both of them.

Solanas became known as the woman who tried to kill Andy Warhol. In her mind Warhol had promised to film her play, Up Your Ass, which is about a prostitute who kills a man. Warhol never made the film; in Solanas’ mind he had ruined her career. When Maurice Girodias of Olympia Press offered to publish her future work and gave her money, Solanas decided that Girodias had tricked her, bought her off cheaply, now owned everything she might ever write, and was probably conspiring against her with Andy Warhol.

On June 3, 1968, Valerie intended to shoot Girodias, but when she could not find him, she shot Warhol instead. This was the act of a mentally ill woman.

Flo Kennedy and Ti-Grace Atkinson embraced Solanas as a symbol of feminist militancy and rushed to her side. They claimed Solanas as one of ours. They visited her in jail. Both Flo and Ti-Grace were identified with NOW. Their attempt to present a mentally ill criminal as a feminist hero made Betty Friedan crazy. Betty viewed Solanas as a man-hating lunatic, not as a feminist hero. Betty feared that NOW would be seen as supporting the murder of men.

Yes, Solanas’ act could be interpreted in feminist terms and, as such, exploited by feminists, but Solanas herself was not a feminist. She had acted irrationally, without a goal; she represented no one but herself.

Solanas hotly denied any association with feminism, which she described as a “civil disobedience luncheon club.”

Touché, Valerie Solanas, touché.

Solanas accused Ti-Grace and Flo of using her to gain fame. Predictably, many years later Wuornos accused me and all those who tried to help her of the same thing.

Ti-Grace resigned from NOW and Flo quit in solidarity with her; Flo formed the Feminist Party, Ti-Grace formed the October 17th Movement. Solanas was diagnosed as a paranoid schizophrenic and hospitalized for three years in an asylum for the criminally insane. In 1988 she died of pneumonia in a San Francisco single-occupancy hotel in the Tenderloin district.

Initially I supported Solanas, just as I supported the issues of self-defense raised by the Aileen Wuornos case. However, once Solanas turned on Ti-Grace and Flo, I respected Betty’s point of view a bit more.

Betty Friedan wanted women with status and power, preferably married to upstanding and powerful men, to represent the feminist movement. She wanted no wild-eyed riffraff, no one unpredictable or too radical, to become associated in the public eye with what she viewed as her respectable and rational movement.

***

This is first of four excerpts from Phyllis Chesler’s A Politically Incorrect Feminist.

Phyllis Chesler is the author of 20 books, including the landmark feminist classics Women and Madness (1972), Woman’s Inhumanity to Woman (2002), An American Bride in Kabul (2013), which won a National Jewish Book Award, and A Politically Incorrect Feminist. Her most recent work is Requiem for a Female Serial Killer. She is a founding member of the Original Women of the Wall.