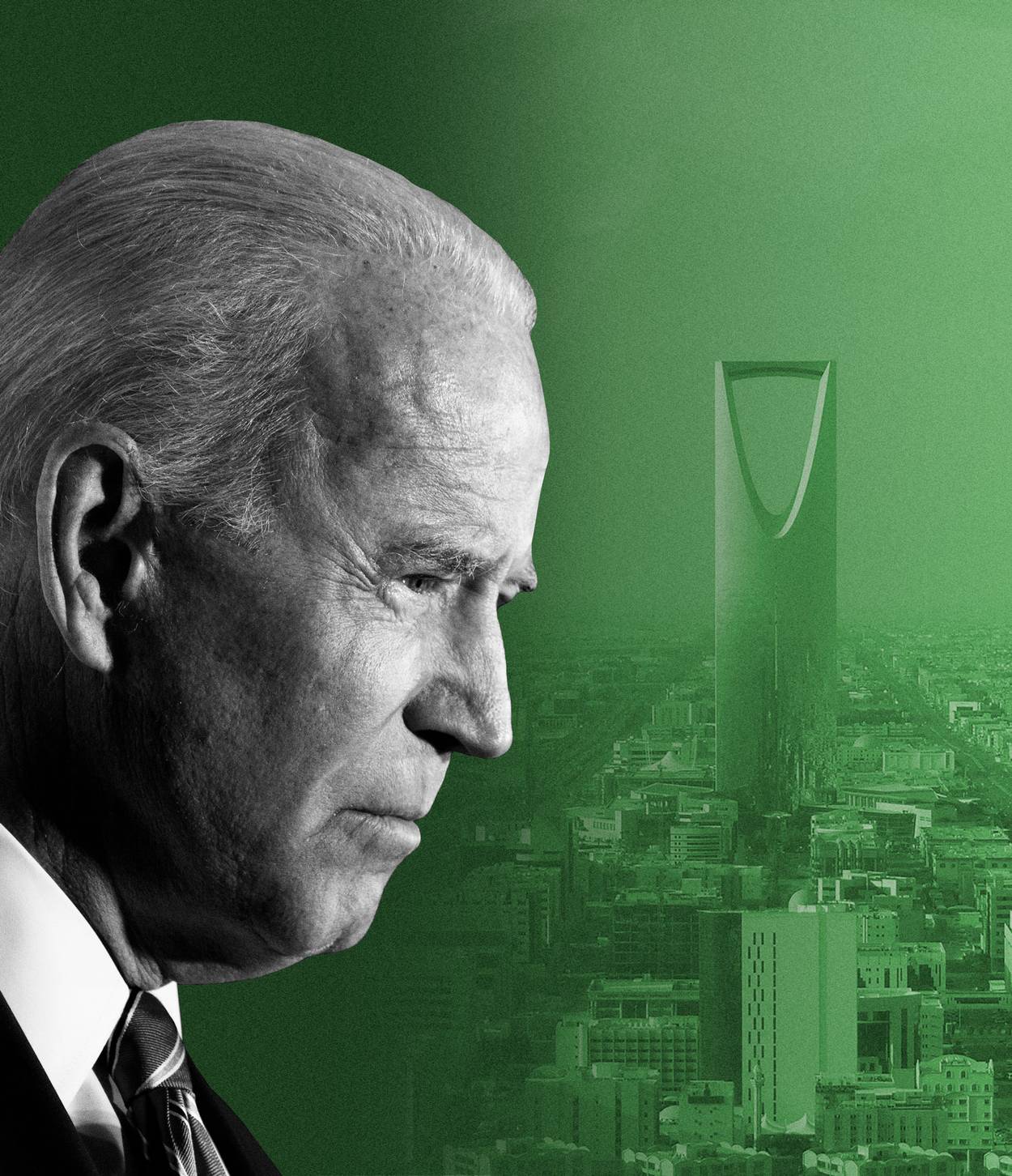

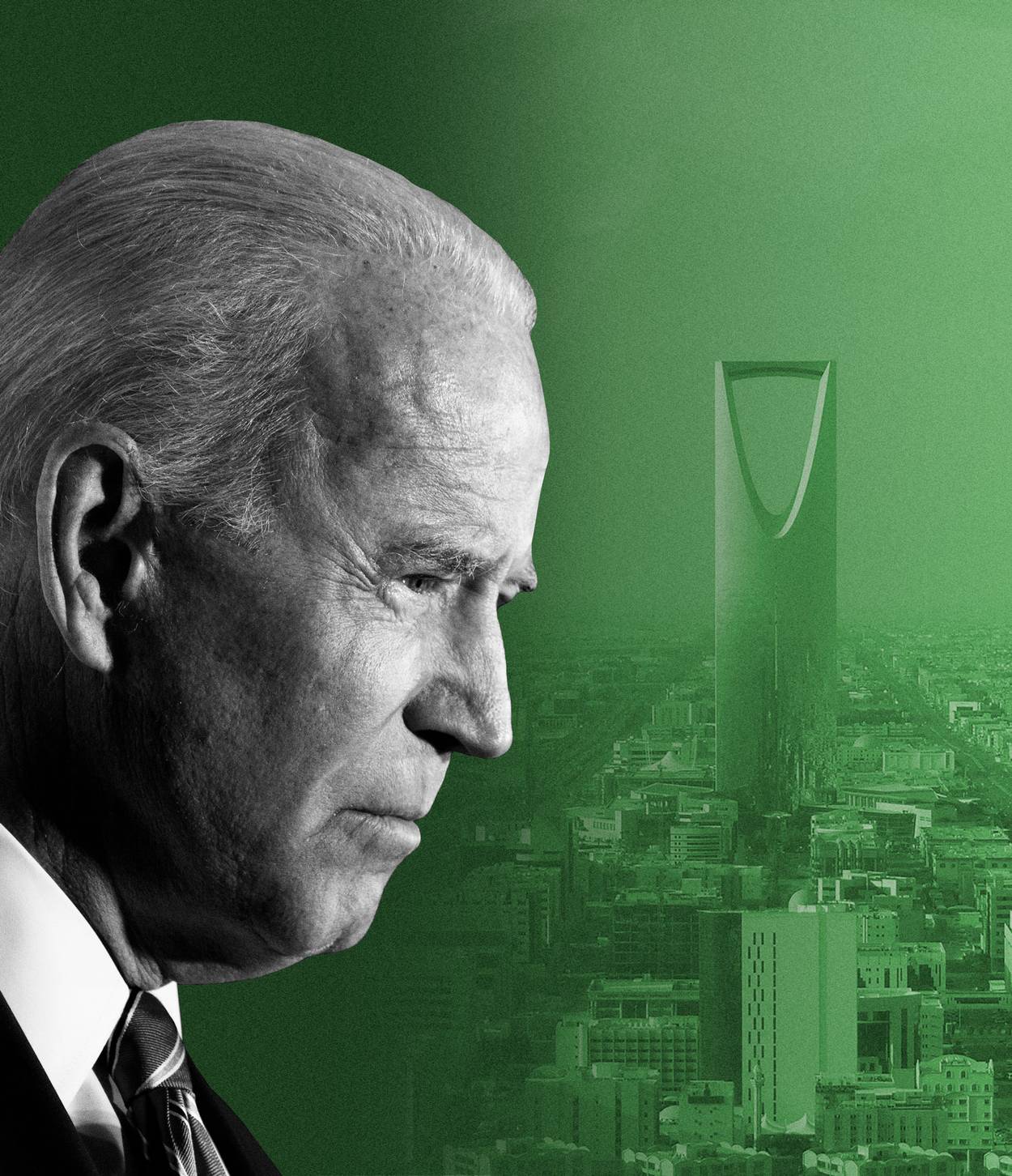

Biden’s Middle East Dilemma

How will the president decide to value the prospects of the Iran deal against $6 per gallon gasoline? By blaming the Saudis.

At the end of October, the Biden administration’s political prospects appeared close to collapse. Consumer prices in the United States surged across the board. Inflation accelerated at the fastest annual pace since 1990. Fed officials retreated from prior forecasts that such price pressures would be “transitory.” Fuel prices, one of the most salient issues in American politics, rose 40% since January. Biden’s poll numbers were underwater.

The administration needed a way out. Unwilling to boost domestic oil output or release crude from the Strategic Petroleum Reserve owing to climate commitments, Biden called on OPEC to increase oil production instead (so much for the climate). The Saudi-led Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries ignored him, and when Saudi Aramco increased pricing, it sent another bullish shock into the oil market. By November, the administration was no closer to resolving the inflationary crisis. But it had found a scapegoat.

“Gas prices of course are based on a global oil market,” Energy Secretary Jennifer Granholm explained to Meet the Press. “That oil market is controlled by a cartel. That cartel is OPEC.” The president went further, calling out Saudi Arabia, the cartel’s linchpin, for failing to produce more “so people can have gasoline to get to and from work.” In a CNN Town Hall, Biden hinted that Riyadh is punishing him personally with expensive fuel. “Gas prices relate to a foreign policy initiative that is about something that goes beyond the cost of gas,” he said. “There’s a lot of Middle Eastern folks who want to talk to me. I’m not sure I’m going to talk to them.”

“Middle Eastern folks” meant Mohammed bin Salman. The president and his team entered office in January having pledged to “recalibrate our relationship with Saudi Arabia,” to “sideline the crown prince in order to increase pressure on the royal family to find a steadier replacement,” and to “make [the Saudis] pay the price, and make them in fact the pariah that they are.” The reasons the administration gave for “changing its approach” to the Kingdom were the 2018 murder of journalist Jamal Khashoggi and the ongoing Saudi war effort in Yemen.

Its determination to reenter the 2015 Iran nuclear deal was left unmentioned, but it was hard not to notice that the revival of negotiations with the still more vicious theocracy in Tehran coincided with renewed public scapegoating of the House of Saud. If the Obama administration had acquiesced to the Saudi intervention in Yemen in 2015 to ease Riyadh’s panic over the nuclear deal, the restoration of the deal seems to provide the regional policy framework for the Biden team’s approach to relations with Saudi Arabia—this time, by freezing out the “murderous maniac” crown prince in order to “put human rights back at the center of our foreign policy.”

And indeed, as president, Biden has refused to engage directly with MBS, who he’s said has “very little social redeeming value.” He released an intelligence report in February that claimed (but did not demonstrate) that the Khashoggi murder was approved by the crown prince. He has held offensive weapons sales to the kingdom in suspension, reduced U.S. support for Saudi operations in Yemen, and withdrawn missile defense systems from Saudi soil, even as Houthi rockets and Iranian drones menace Saudi cities and oil facilities. His “foreign policy initiative” is backed by feverish legislative activity, too: Pending in the 117th Congress are no less than 10 bills meant to hit the Saudis in general, and MBS in particular, for Khashoggi and Yemen.

It’s possible an American Metternich could persuade Riyadh to engineer an oil price collapse that would aid his own political survival while continuing to whip it in public for crimes against morality and aligning with its strategic rival. But Joe Biden probably can’t. There seems to be some dawning recognition, in fact, of the Saudis’ limited but real ability to scupper both the Iran deal and Biden’s political fortunes: In recent weeks, the State Department approved the potential sale of $650 million worth of air-to-air missiles to Riyadh (Rep. Ilhan Omar has filed legislation to block it) and a U.S. bomber (accompanied, at different times, by Saudi and Israeli fighter jets) conducted a patrol mission around the Arabian Peninsula. Ahead of upcoming nuclear negotiations with Iran, the White House is also sending Special Envoy Robert Malley to Riyadh (and Dubai and Jerusalem) for “consultations.”

But if the administration expects these concessions (such as they are) to reassure the Saudis, they’ll likely be disappointed. The crisis threatening U.S.-Saudi relations is not that the president prefers to deal with the crown prince’s father, the 85-year-old King Salman, or that some House reps would like to pass the MBS Must Be Sanctioned Act (H.R. 1511), or that Democrats in general are striking an “increasingly standoffish attitude toward the kingdom,” as one typically navel-gazing U.S. press report put it.

The real crisis is of a different magnitude: Saudi Arabia is terrified not of cold shoulders or even of sanctions, but of the fact that the United States seems intent on reaching a diplomatic condominium in the Middle East with the kingdom’s existential enemy—even, if necessary, at the expense of Biden’s political fortunes; and even if it means—as it did in Kabul—watching its former allies fall.

A quick look at a map helps explain why the Saudis might have trouble calming down no matter how many times Mr. Malley visits Riyadh. To the north they see an Assad near-victory in Syria (midwifed by the U.S. and Iran), the defeat of Sunni power in Iraq (also courtesy of the U.S. and Iran), and a Hezbollah-dominated Lebanon. To the south they see a Yemeni state ground into dust in the name of another Iranian client. Across the Red Sea is a civil war in Ethiopia, a coup in Sudan, and chaos in Libya (abetted by the U.S., again). Only a few hundred miles across the Persian Gulf is the imperial Iranian regime, which is also active in undermining the Sunni monarchy in Bahrain, and meddling in Saudi Arabia’s eastern provinces. Malley has been the regional point man for the Iran nuclear deal for nearly a decade, in both the Obama and Biden administrations. Riyadh does not see any chance that he could be persuaded to change course.

This is the lens through which the Saudis view the Biden administration’s efforts to secure Iranian reentry into a limited arms control agreement—one that would release the cash resources the Revolutionary Guard Corps needs to make its regional operations even more expeditionary. Offers of prior “consultations” are unlikely to assuage the Saudis, who remember the Biden team from the Obama years. Back then, Saudi pleas had no effect on U.S. attempts to realign not only with Iran but with Erdogan in Turkey, the short-lived Muslim Brotherhood government in Cairo, and with Hamas in Gaza. So horrified was Riyadh by the Obama administration’s double embrace of its Sunni Islamist rivals and its revolutionary Shi’a adversary that it felt compelled into previously unthinkable cooperation with Israel, into more open reliance on a possible nuclear warhead deal with Pakistan, and into a frenzy of poorly conceived self-help initiatives: the intervention in Yemen, the arrest of the Lebanese prime minister, the diplomatic crisis with Qatar.

One need not ever forgive the Saudi regime its many heinous sins to recognize that the Obama-Biden era in Saudi history has been an unmitigated diplomatic and military disaster. The main accomplishment of the realignment so far has been a reduction of U.S. influence in Riyadh without any gain in leverage over Tehran. When the Biden administration has the midterms in its sights and asks Riyadh for lower gas prices, and for acquiescence to its Iranian nuclear policy, you can almost hear the spinning heads in the Saudi court explode.

The main accomplishment of the realignment so far has been a reduction of U.S. influence in Riyadh without any gain in leverage over Tehran.

What’s more, throughout its history, the House of Saud has always turned to extremists in times of desperation like the current one: When the first Ibn Saud embraced the fundamentalist Muhammad ibn Abdul Wahhab in the 18th century, forging the political alliance that rules the kingdom today; when Abdul Aziz, the founder of the modern Saudi state, turned to the Ikwhan, a fanatical death cult, to unite the tribes of central Arabia; in 1979, after the dual shocks of the Iranian revolution and the seizure of the Grand Mosque, when Saudi money flooded the Salafi mosques and madrasas that would nurse the men and ideas behind 9/11. But at least for now, MBS is pursuing what might be regarded as his own fanatical program of modernization. From the standpoint of U.S. interests, that is something so elusive in the Middle East that Americans have to rub their eyes to recognize it: It is, quite possibly, a good thing.

The crown prince might eventually turn out to be a mere “psychopath” who careens his finite military power into a ditch in the Sarawat mountains and leaves only a wet spot where his political opponents once stood. But what we know now is that he has made some actual progress toward doing what the State Department had only imagined in daydreams: breaking the power of the Wahhabi clerics. He has revoked the arrest power of the country’s “religious police,” who can no longer control or punish the public behavior of ordinary Saudis. He has likewise removed their veto over education reform, female labor force participation, and the token but culturally central matter of a woman’s right to drive a car. He has reduced the ability of the Palestinian issue to impede strategic cooperation with Israel. For the first time in Saudi history, the royal court is attempting to defang the clergy, a risky gambit even for a “psychopath.”

Whether all this leads to an Arabian Sweden, or to MBS being dangled from a window at the Ritz Carlton by his bone-saw-wielding cousins while Wahhabi judges cackle from the parking lot below, is not yet clear. But a society this fragile undergoing change this rapid while surrounded on all sides by violent disorder runs a real risk of implosion. Americans may not like the Saudis—and they have plenty of good reasons not to—but it is hard to see what the U.S. interest would be in watching them go down in flames to whatever al-Qaida affiliate would most likely take their place. That the monarchy which stewards the Two Holy Mosques, the world’s second-largest proven oil reserves, and some of the most critical transport routes in Eurasia is so disposed to U.S. interests that it prices its oil in dollars, loans out air bases to the U.S. military, provides a crucial export market for the U.S. defense industry, and furnishes Washington with human intelligence against Islamic terrorists is in every way an accident of history, and it won’t last forever. In the nearly eight decades since Valentine’s Day 1945, when Franklin Roosevelt and Ibn Saud met on the USS Quincy in the Suez Canal, there have often been grounds for wondering whether the costs to U.S. values are worth the benefits of entente with Saudi Arabia. But there are good and serious reasons that U.S. policy since the early Cold War has been, on balance, to maintain the status quo.

Which is what makes one question the Biden administration’s decision to treat the kingdom in public as a freakish cesspit of human rights violations whose barely tolerable cooperation in the oil market and in nuclear negotiations can be bought or compelled on a whim. And indeed, it seems the Saudis are taking the hint, as they start to explore expanded relations with China and Russia to make up for waning American support. To hold MBS unilaterally responsible for this deterioration in U.S.-Saudi relations has been an expedient way to paper over the deterioration in Saudi Arabia’s regional position that was in many ways facilitated by the United States. To insinuate an official U.S. preference for an alternative to MBS is, at best, a wildly irresponsible posture that seems inimical to any legible calculus of U.S. interests.

Nor do wishful American fantasies about finding a replacement crown prince seem likely to come true. With the support of his father, MBS has—according to a Congressional report from last month—not only neutralized political opponents and marginalized the Al-Wahhab, but has centralized control over the country’s security forces and intelligence services. If the White House wants to boycott his de facto leadership in a fit of self-righteousness, it quite obviously can, but its invocations of Jamal Khashoggi and the tragedy in Yemen are unconvincing, even offensive. America’s current national security leadership presided over human catastrophes in Libya and Syria that equal the horrors of Yemen; the humanitarian disaster about to engulf millions of Afghans has not elicited a fraction of the outrage accorded to the murder of a Washington Post contributor.

The more relevant question now is which horn of an increasingly urgent dilemma Biden will choose: Put the Iran deal on the back burner, or lose what leverage the United States has over the world’s swing oil producer. As winter approaches, and talks with Iran resume in Vienna, the only thing that seems certain is that one of the most consequential regimes in the world has also become one of the most frightened, because it believes its sworn enemy to be on the brink of a nuclear breakout—aided by Washington.

Jeremy Stern is deputy editor of Tablet Magazine.