Bloomberg’s Out

A Jewish billionaire’s final campaign

Early this Tuesday morning at El Pub, a beer and shot bar that doubles during the work day as a greasy spoon diner in Miami’s Little Havana, I glimpsed the first sign of trouble for Mike Bloomberg’s $500 million wager, a bet by the ninth-richest man in the world that in just four months of campaigning he could recode the Democrats’ presidential electoral process and initiate a viable path forward to July’s Democratic Convention in Milwaukee. Eschewing precedent, he forwent participation in the Iowa caucus and New Hampshire primary, instead using his vast wealth to focus on swing states and Super Tuesday’s 14 primary contests—a one-day megavote that would measure with sober precision the outcome of Bloomberg’s political gamble.

But problems appeared even before the voting booths had opened. There was the disastrous debate performance, followed by headlines, fresh poll numbers, and campaign imagery that splashed across the smart phones and newspaper front pages of Team Mike’s staffers in their rented SUV’s and rented buses and which were now being flipped through by the half dozen men sitting at the counter of El Pub over breakfast plates of fried eggs and cortados spiked with poured hills of white sugar.

Former Vice President Joe Biden’s overwhelming Saturday night primary victory in South Carolina was the anointed legacy candidate’s first primary win after three previously failed presidential campaigns, and a cardiac resuscitation to what was shaping up to be his fourth. In short order Pete Buttigieg, the cruise-ship Obama impersonator, dropped out, followed by Minnesota Sen. Amy Klobuchar, moderates both who on Monday night came down to Dallas to share the stage and pledge their support for Biden’s campaign, joining a groundswell of other endorsements declared by every Democratic establishment figure whose pulse had quickened at the prospect of a Bernie revolution. Bloomberg was now the last moderate thwarting the vice president’s rightful claim to the nomination of a political party run not by Napoleonic billionaires but party hacks, who have feelings, too.

Day laborers rode past shops selling cigars, doughnuts, beers, and haircuts to hop off their seat-worn Trek mountain bikes and grab coffee and breakfast sandwiches on Cuban bread at El Pub’s sidewalk counter window. Team Mike staffers congregated the 30 or so members of the press on the curb, local media with cameras on shoulders and national outlets, here to watch Mike Bloomberg order his own coffee and sit down with the first of what would be a day’s slog of events with minor politicians and mayors with names that no one knew outside of Florida, a roster of endorsements that appeared like a hastily scrambled attempt to boost Bloomberg as his numbers continued to sink. The cloud hovering over Bloomberg’s political future was grimly mirrored in the looming pandemic of the coronavirus, two cases of which had been confirmed in Florida, prompting a statewide public health emergency that lent a fine undercurrent of menace to Bloomberg’s scheduled seven stops in three Florida cities among a population weaponized by contagion.

Perhaps it was the fear of death by infection or the inevitable blues of churning out nearly identical content to feed the social media machines, but by the time Bloomberg, dressed in khakis, loafers, and an open-collared shirt, sat down with his table of nationally anonymous Floridian somebodies, there were few among the press core without furrowed brow or heavy sighs as nothing the table was saying could be heard from our set-back position and it was clear that the staffers were not going to allow journalistic intrusion. After photos, “thank you press, OK keep moving, press,” the disgruntled media were escorted out of the dining room and told to walk down the street to the Miami field office to wait for Bloomberg’s next appearance, a shortsighted move that did little to shrink the growing pink elephant of Bloomberg’s electability. A few moments after Bloomberg left the table and began his own trek down to the office a scrum spontaneously formed around the former mayor, firing off questions about Bloomberg’s decision to stay in the race as an act to siphon off votes from Biden.

“I think I can run the country better than anyone else,” Bloomberg said, thinly disguising his frustration.

Will you stay in the race?

“We’re here to win it,” Bloomberg said with evident agitation. “I don’t understand what you’re talking about. Go ask everyone else how long they’re going to stay in.”

But the race has changed in the last few days …

Bloomberg snapped back: “Nothing’s changed in the last few days. We’ve had four primaries in which three different people won.”

Up until this past weekend, Team Mike’s working thesis had been simple and self-evident enough. Bloomberg was the calm, composed ying to Trump’s volatile, unstable yang, an actually self-made business titan who with civility and appreciation for the longstanding norms that afforded him his fortune represented everything Trump was not. In this way, Bloomberg argued, he was Trump’s superior in all facets, and because he was so observably better than Trump, voters—an abstract quantity of rational actors that behave in simulations much as they do in real life—would anoint Bloomberg the victor over Trump in the general election. All he had to do was make it to the general.

Since last November, Team Mike had largely ignored the existence of other candidates and operationalized their concept through hundreds of millions of dollars of emotionally provocative, market-tested, Trump-critical ads that flowed steadily into the ears and eyes of tens of millions of Americans, almost all of whom came to know the once-Republican and three-time mayor of New York not in person on the campaign trail, or in interviews on 60 Minutes, or on the debate stage with the rest of the candidates, but rather through what became the ceaseless unavoidable narrative of Mike Bloomberg’s attributes, character, and fitness for the White House, as told by Mike Bloomberg and his campaign. But as the cracks in Bloomberg’s story began to widen, a formidable cognitive dissonance emerged between the Bloomberg projected into the American consciousness by Bloomberg’s own wealth and the solidifying perceptions of Bloomberg’s political vulnerabilities as gleefully hammered on by his rivals.

There was of course the memorable public evisceration of Bloomberg by Elizabeth Warren at Bloomberg’s first appearance at a Democratic debate in late February. It was a terrible tactical decision by his camp to even show up, in part because his presence amounted to a tacit endorsement of the debate’s importance in the grand political scheme and undermined the Bloomberg project to run an alternative direct-to-consumer effort. That ontological mistake was compounded exponentially by Bloomberg’s egregious lack of preparedness to answer basic questions or thwart inevitable attacks about the baggage of his mayoral record—discriminatory stop-and-frisk policies in New York, his longtime support for redlining, or the NDAs he foisted upon women who’d brought forward charges of sexual harassment and discrimination against Bloomberg and his company. Apologizing for these mistakes only compounded them, as more skeletons from Bloomberg’s past threatened to come tumbling out of the closet—including the birthday gag book a Bloomberg employee gave his boss in 1990, with quotes Bloomberg did not deny and which include his observation of an competitor—“Cokehead, womanizing, fag,” and ready-for-prime time bon mots like: “The three biggest lies are: the check’s in the mail, I’ll respect you in the morning, and I’m glad I’m Jewish.”

As the cracks in Bloomberg’s story began to widen, a formidable cognitive dissonance emerged between the Bloomberg projected into the American consciousness by Bloomberg’s own wealth and the solidifying perceptions of Bloomberg’s political vulnerabilities.

But events were moving too fast for Bloomberg’s opposition to put the gag book into play. In the Miami field office a few blocks down from El Pub, paid field staffers tried to maintain an air of busy purpose as they hovered over pop up tables in a sparsely furnished room, but there was a frantic nervousness in their affect. In the other room, their boss was about to appear before a room full of 40 members of the press shoved tightly around a podium beside a few requisite American flags.

The rising Miami sun creeps in through the cracked vertical blinds and dirty panes of glass that look out over a parking lot filling up with pedestrians who have caught sight of the camera crews all sweating in anticipation for someone to come stand at the mic. A perspiring man of great girth saunters down the street until he spots the crowd staring at the room of cameras. His face a bright red and brow twisted up, he looks as though he swallowed a hot stove, sweat sliding down his cheeks onto his white rubber sandals.

Bloomberg appears and the field office staff dutifully greets him from the other room with chants of “Get it done, get it done,” a riff on the guaranteed-to-be-forgotten-by-Friday campaign slogan “Mike will get it done.” As Baldwin said once, (of Mailer, actually), and which is applicable here of Bloomberg, “No one is more dangerous than he who imagines himself pure in heart: for his purity, by definition, is unassailable,” but at least if Bloomberg thinks himself as pure he doesn’t need a great deal of time to prove it. His stump speech, a promise to not only get things done, but big things done, on health care, gun safety, climate change, and income inequality, while short on any details is thankfully short all around, and he ends with rosy optimism, as if, for him at least, everything still might be OK.

“We have to remind people that this is still the greatest country in the world. I think we forget that. We look at our faults rather than our successes,” he says with the vigor of an assistant middle school track coach. “It’s the most wonderful country in the world.”

To no one’s surprise in the room except apparently for Bloomberg himself, the press lunges forward with the continued line of inquiry on Bloomberg’s viability, and the candidate is immediately thrown off balance.

Aren’t you taking votes away from Joe Biden?

“Well it goes both ways,” Bloomberg says defiantly. “Have you asked Joe if he’s going to drop out? When you ask him that then you can call me up.”

Is there pressure today going into Super Tuesday—do you drop out of the race if—

“I have no intention of dropping out, we’re in it to win it,” Bloomberg says, and on cue his field office in the other room sends up dutiful paid cheers.

But Mayor … Mayor …. What states do you intend to win?

“I don’t know if we’re gonna win any,” Bloomberg says with a whine. “You don’t have to win states, you have to win delegates.”

Do you want a contested convention?

“Well I don’t think I can win any other way. But a contested convention is a democratic process,” Bloomberg says, his voice rising with agitation. Why so many questions?

Though well paid, with salaries for the field organizers starting at $6,000 a month, communications staff earning $10,000, and top aides hauling down $30,000 monthly, the Bloomberg staffers seem to see themselves as spectators to the combat between Bloomberg and the press. Maybe they want to give the boss a chance to fend off the press himself, and show his mettle. Or maybe they know the questions are going to come anyway, and are unanswerable in any way that might benefit their shared enterprise. By the door one staffer types into a staff group text chain, the message appears in the blue bubble: “NEXT STOP THE WHITE HOUSE.”

Not quite yet, though. First, it’s goodbye Miami, hello Orlando, where the field office is downtown, slick, clean, and bright, already filled up with a few hundred of the city’s well-groomed, middle-aged Bloomberg fans and the sounds of a DJ blasting Jay-Z’s “Empire State of Mind,” the song that Bloomberg plays religiously at his stops. Tanned men in the Orlando business casual uniform of sports coats, jeans, and suede driving moccasins tap out the beat with their sockless feet. Guests loiter in a back room eating a catered lunch. One man in his 60s stands alone in a Bermuda Beach baseball cap muttering to himself.

Of the 150 or so in the office, one grouping of a few dozen bodies stands roped off among some folding chairs. Behind them are the broadcast and print press. Against the wall on the opposite side of the room is another block of crowd. They’re actually the background, the scene-setting carefully curated by staffers attuned to the right proportions of Latinos, blacks, and middle-aged whites that will allow the maximum number of Americans who catch this clip at home to see fractions of themselves in the supporters who will literally stand behind Bloomberg waving his signs and wearing his T-shirts.

The promise here that bubbles up regardless of today’s outcome is the intimate proximity to the potency of presidential celebrity and power—to witness the free-world leader, to know of this moment when some small detail of body language or speech cadence may register with the clarity of their true personality such that every time you saw them again at a press briefing on TV or watched the clip in your feed or saw the face glossed up on the cover of a magazine you could recall back, almost without thinking about it, the several seconds in which you yourself stood in the same room on equal footing with a person just like you, someone you knew briefly and immediately, who went on to become president.

Bloomberg’s political proposition is one of offering those here a renewed confidence in the process of giving one over to a political figure, that he will be rightly trusted and understood. He will cleanse and clarify, bringing sanity to the race to overturn a demagogue while also having to vanquish a head-in-the-clouds revolutionary and a mentally compromised establishment figurehead who can’t finish his sentences and appears to be visibly suffering from some horrible disease. Regardless of how pessimistic the press might be, there’s reason to believe that if Bloomberg says he’s in it to win it, with all that money to spend, he’s going to stick it out.

People starting to flag here waiting now for almost 30 minutes—the blood sugar drooping as free pizza passes through the digestive track. Despite the wait and plummeting energy those close to the ropes continue to keep their arms hoisted at eye level, with their phones in camera mode. And here he is! Chants start up, “Get it done! Get it done!”

Bloomberg gets intro’ed by Orlando’s Mayor Buddy Dyer, and when Bloomberg gets the mic he does his usual opening of a joke, talking about how everyone has nice things to say about Dyer, “And for mayors that’s really unusual. Because everyone wants to know, in your case probably not, did you plow the snow the last time you had a storm here,” Bloomberg says as the crowd responds with the requisite polite laughter to a snow joke in Florida.

He stumps his stump, though it seems like the barrage of inquiries from the day has started to take his toll.

“People keep saying why should they vote for me and it’s a legitimate question,” Bloomberg says. “My answer is, we need a manager who can actually run the country, like addressing gun violence. What happens with legislators is they just pass bills, most never get funded, they certainly don’t get implemented, and nobody ever checks to see whether it helped the people.”

“The legislators just don’t do it. You need a manager,” Bloomberg says, raising the interesting image of a Bloomberg presidency that removes the poorly optimized branch of government known as Congress and finally consolidates power more efficiently in the White House.

At every opportunity Bloomberg takes his digs at Trump. As he starts to wind up with a nod to COVID-19 he uses the oncoming pandemic as an active metaphor for the scourge of Trumpism he’s out to eradicate from this fair nation.

“We’re in high dudgeon in the newspapers about a virus, but compared to [gun violence] I’m not suggesting we don’t have to worry about the virus, but we have a virus that’s taking over our country and we have to do something about it,” Bloomberg says to cheers. Before the press gets a second to come forward with cameras and more questions, the DJ doubles the volume on “Empire State of Mind” allowing Bloomberg to shout hellos and take pictures with the crowd.

Press out, on the bus, over to Pulse, the gay nightclub where three years ago 49 people were slaughtered in one of the deadliest mass shootings on American soil. We’re here because Bloomberg’s doing a photo op with Maria and Fred Wright, parents of a victim in the shooting. The club is closed and surrounded by a memorial, a wave-shape structure with photographs of the victims and images from the dozens of vigils held across the world. Staffers ask us to be mindful of where we are, a condescending request or a lack of faith in the situational awareness, perhaps born from a sensitivity to the Miami ambush this morning.

Bloomberg walks with the parents solemnly to lay flowers and a wreath at one end of the memorial. He gives the crying mother kisses on both cheeks and the father steps forward for a group hug. There’s real palpable emotion emanating from the parents of a slain child projected outward into the image and potential of Bloomberg’s candidacy, whatever it might mean, real or imagined, for restricting guns and tamping down violence and providing some recompense, maybe. It’s an intimate moment, and standing with the 30 members of the press feels vulgar and invasive.

A melodic music emanates from an unidentifiable source around the memorial, a soothing inoffensive gurgle hybrid of Brian Eno’s airport tunes and the warm bath of electronic spa music. It’s drowned out over and over again by the surging traffic of brisk cars and diesel tractors upshifting along the adjacent highway, which belies salubrious effects of the music and the memorial.

Bloomberg walks off to his tinted Cadillac, the press to our bus. We pull away from the memorial. The wreath hangs precipitously on a thin, three-legged stand, the flower petals rippling softly in the breeze. In the Florida sun it looks bright and healthy, though with nothing to secure the wreath to the stand or the stand to the ground it’s inevitable that a strong wind will pick up both and scatter them across the street.

***

On the flight to West Palm Beach, the staff looks beaten and tired, the media looks beaten and tired, the flight attendants look beaten and tired. People don’t talk. They Twitter-scroll, or frantically turn the footage of the day into clips on their large-screen laptops to become content in the same feeds they watch now. Hours pass before tonight’s rally to celebrate Super Tuesday, which will be the biggest and last night of Mike Bloomberg’s campaign for president.

It’s 7:15 p.m., a mild Florida evening, nice breeze. Outside the convention center there’s hundreds of Trump supporters waving signs in favor of gun rights beside Trump flags. It’d been a few years since I was last among Florida’s Trump country—and it’s clear that now there’s an exuding confidence among the folks here, a real sense of accomplishment and assuredness of what they feel, with some reason, is an eight-year run in the making.

There’s a truck set back from the road with a massive generator powering a spotlight underneath an 18-foot blue Trump flag that flaps with aplomb from the truck bed. The owner of that truck looks over it proudly, said it was time to really step up his support for the man they love.

I say I’m surprised there’s any animosity for Bloomberg here—he seems like one of the best matchups for a Trump walkover should he even get the primary.

“Mini Mike?” The man says smiling, holding his hand way down low to the sidewalk. “Oh that’ll be nothing but a tiny speed bump, we’d roll right over him. But we’d roll right over any of them.”

Of the Democrats generally, the man observes that the problem starts in the schools. “All the teachers now are lesbians,” he says, offering a theory I admit to him I had not yet heard. “It’s true, all these boys, wussies,” he laments.

The West Palm Beach convention center is the vast kind of slick banquet space where you can spend a lot of money. It’s perfect for a political event when a campaign wants to splurge. Outside the main hall, open bars dole out wines and beers beside long tables of cupcakes, pulled-pork sliders, and spinach flatbreads. The massive main room is dominated by a 3-foot-tall stage to the back where a podium stands over a throng of several hundred people bouncing up and down like they are at a sold-out concert. On the wall behind the podium two gigantic screens hover with a steady stream of the library of slick video ads that play between an endless supply of mayors and former mayors culled from all over Florida.

Above the crowd a 30-foot boom camera makes panoramic sweeps back and forth in a perpetual slow-moving arc; as it hovers it generates clip after clip of the crowd cheering at itself. Along with the clips are the Bloomberg ads on a long slinky loop, a procession of expensive 30-second spots populated by actors and enthusiasts who look just like the people in the crowd. The themes of the videos are specific, the ideas familiar and vague—gun laws, climate change, job creation, the spoken lines the kinds of things a reasonable person might mention to a like-minded acquaintance on Sunday morning at the farmer’s market.

The lights are dimmed low and the screens shine bright. Behind the crowd a fog machine kicks out spurts of artificial smoke which at first looks like signs of a small fire. The fog rises over the crowd and holds the red and blue stage lights in its temporary sheen.

The mayors that come onto the stage to speak the Bloomberg gospel all blend together, just like the ads, and it is difficult to tell them apart.

We’re not against people owning guns, we’re not against gun owners.

We believe that there are policies, and the data proves it, that will save lives.

The only option we have is to get out and do something.

In between the talking points the mayors and former mayors tell of Mike’s American dream story—a wobbly vision of a billionaire everyman who despite his unimaginable wealth will always represent the platonic ideal of success that hangs like a carrot in front of every man, woman, and child in America. That Bloomberg is both the embodiment and a prime mover of social changes and policies that have greatly impeded this opportunity goes unmentioned.

“Listen, Mike’s self made, he started from nothing, he didn’t hit a triple and think he started on third, he started from the 40, from the bottom of the barrel, he went to the top himself—that’s who Mike Bloomberg is,” one mayor says. “He wants everyone to have the opportunity that he has, because he believes in the American dream, and that’s what we believe in as Americans. We’re in this together, folks!”

“Don’t tell me in America now we demonize successful people. Not on our watch. We aspire to be successful, it is part of the American belief,” former Tampa Mayor Bob Buckhorn says, as someone from the back yells “Boo, Bernie!”

“Are you ready to get in the fight? Are you ready to stand with Mike Bloomberg? Are you ready to tweet and Facebook and Twitter and Instagram!? West Palm Beach!”

The mayors take a break and in between the advertisements and live crowd shows the TV screens start flashing snips from CNN, clips hastily assembled from the returns now coming in. There’s word that Bloomberg won his first delegates in American Samoa, It’s not a state, it’s a territory, but Bloomberg trounced Tulsi Gabbard there, and picks up four delegates.

The clip runs too long though, either a gaffe or an editor trying to poison the well, and the CNN delegate leaderboard suddenly appears, showing Biden and Bernie racking up points as Bloomberg is stuck way down at the bottom. The screen glitches and the American Samoa victory flashes back and the crowd roars again before staffers usher up a stream of the most enthusiastic crowd onto the stage into the rafters set behind the podium under the screens.

More ads, more mayors …

To make sure the economy works for all Americans

Mike takes on the biggest challenges and he wins

Some of the crowd are sick of waiting through another speaker just to see Mike Bloomberg. An older couple ask me if I know when he’s coming on and I tell them I’m not sure. They hold plates of half-eaten dessert and plastic cups of chardonnay.

The man throws his cup out. “Let’s get the fuck out of here,” he says.

At the garbage can a younger man with a mustache and a FORD hat stands beside two cups of beer on the lid of the can. “I wonder if they’re afraid of the numbers coming in,” he says as he watches the couple leave.

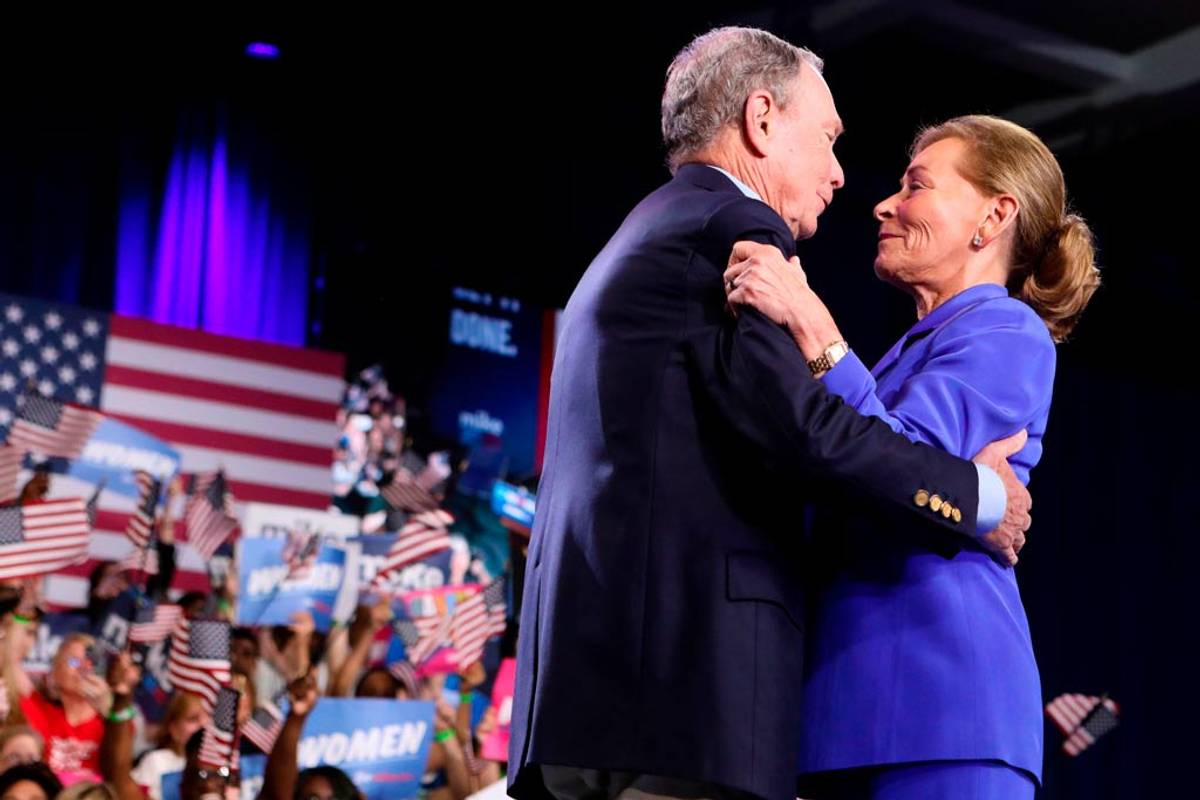

Judge Judy comes to the stage—a proud Floridian she’s wooden and uncomfortable reading the teleprompter, explaining that America “doesn’t need a revolution, it needs a little tweaking.”

“Government with grace” she says, and one can’t decouple this phrase from the image of the faux legislative theater of a small claims stage court that has been home to Judge Judy’s act for the past two decades.

By the open bars a few hundred are watching CNN on the television screens as the first wave of results start rolling in behind American Samoa.

Two friends came here after they’d seen people eating free food on the local ABC newscast.

The younger of the two, a man in his 30s, looks worried. “I just hope I don’t get the coronavirus,” he says.

“Yeah, my girlfriend stayed home, didn’t want to risk it,” his friend adds.

We entertain the possibility that this event might be one of the last large public gatherings we’ll all be at for a long time, if the virus continues to quarantine the public off from itself. Soon, we’ll all have to stay at home, ration our food, working remotely as we experience the general culture and word of the outside world entirely online. Our worlds will shrink down to the dimensions of our digital devices.

“Better enjoy this bar while we can, then,” the man jokes, and they raise their glasses as I go back past the press pit tables where dozens of media convert the raw video files coming off the cameras on the risers in front of them into digital clips waiting to become new scrolling material.

There’s at least 2,000 people here, maybe many more—dozens are visibly drunk in the dark.

Bloomberg emerges in his best Florida early bird special attire, crisp khakis, pressed open color shirt under a blue blazer.

“Unlike the president I didn’t come here to golf,” he says, getting more than the usual response to his opening stump joke. “Came here because winning in November starts with Florida.”

“My message is simple, I’m running to beat Donald Trump,” Bloomberg tells the crowd, and the possibility that this was all a half-billion-dollar play to take a few digs at Trump starts to bubble up from the absurdity of this event.

“As the results come in—here’s what is clear: No matter how many delegates we win tonight, we have done something no one else thought was possible,” Bloomberg says, a hint of recognition that the delegate count might be lower than anyone anticipates.

“In just three months we’ve gone from 1% of the polls to being a contender for the Democratic nomination for president,” he claims. A few minutes later, he’s already wrapping it up.

“Tonight we prove something very important, we prove we can win the voters who will decide the general election, and isn’t that what this all about?” Bloomberg asks, reading from a teleprompter script for a night that never happened. The next day, he dropped out of the race.

***

Read Tablet’s 2020 Presidential Election coverage here.

Sean Patrick Cooper is a journalist who has contributed narrative features and essays to The New Republic, n+1, Bloomberg Businessweek, and elsewhere. His first book, The Shooter at Midnight: Murder, Corruption, and a Farming Town Divided will be published in April 2024 by Penguin.