Brick-and-Mortar Romance

Jewish values fuel The Ripped Bodice, the country’s only bookstore to focus exclusively on the romance genre

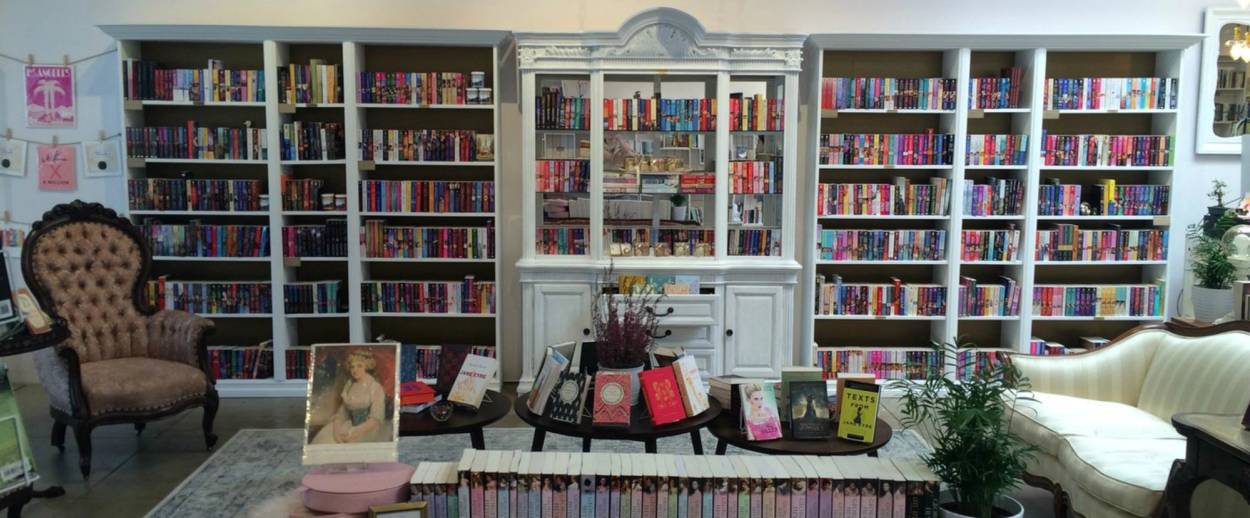

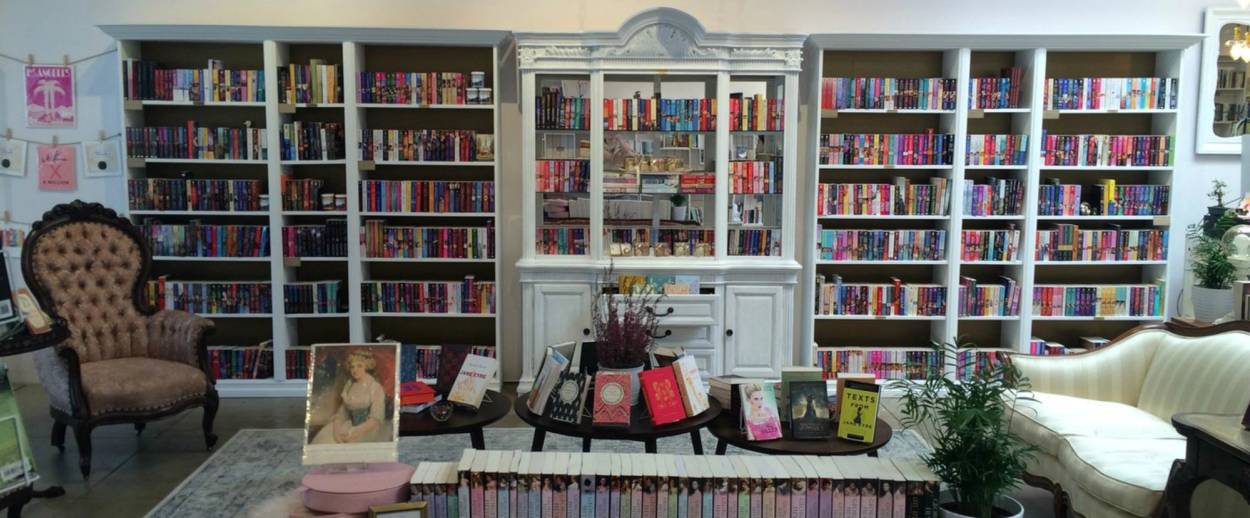

“What are your daughter’s favorite books?” asks Leah Koch, 24, as she leads me around her Los Angeles store, The Ripped Bodice, to find gifts for Josie, 15. The Ripped Bodice shelves books by genre, so we bypass Bikes & Tats, Dragons, Highlanders, Bondage, Romance Theory, Time Travel, and Erotica and hit the Young Adult section.

I’ve told her that Josie loves Jane Austen and comic books, so Leah hands me a young adult novel by Sarah MacLean (who also writes feminist adult romances and reviews romance for The Washington Post) about three teenage friends in Regency London who get involved in espionage and mystery. Then she points me to a snarky novel about the personal assistant to a demanding superhero; then a choose-your-own-adventure book that lets the reader revisit and revise all of Elizabeth Bennet’s decisions in Pride and Prejudice. Done! I treat myself to a contemporary romance with a Jason Momoa-esque shirtless cover model, from a series called Beards & Bondage, because hell yes. I also buy a beauteous Great Gatsby-themed gin, juniper, and daisy-scented candle from the Banned Books collection—the library card on it explains when and where the book was banned. Leah even finds me a Newbery Honor-winning middle-grade novel from the Kids section for Maxie, 12, about a girl who moves from New York City to small-town Wisconsin to help her aunt run a local diner. “This was my favorite when I was her age,” Koch tells me.

It’s clear that at The Ripped Bodice, customer service is paramount… and romance (as well as reading in general) is a broad tent. Welcome to the only all-romance bookstore in the USA.

It’s owned and run by Chicago-bred sisters Leah and Bea, 27, with assistance from Bea’s one-eyed, large-eared, sweater-wearing dog, Fitzilliam Waffles. Bea, a Yale grad with a masters degree from NYU (her thesis was called “Mending the Ripped Bodice”), adores historical romance. Leah, who graduated from USC with a degree in Visual and Performing Arts Studies, is into contemporary romance and erotica. Together, they cover the waterfront.

Leah is also responsible for the look of the store—there’s a huge Calder-esque mobile made of open books; sweet home photos of the sisters as kids; a staircase papered in yellowing pages from vintage romances; comfy chairs and couches; steampunk-y, heart-shaped Edison bulbs of varying lengths hanging over the register. Next to the front door is a pink garbage can filled with large pieces of cardboard—“for protest signs,” a helpful hand-lettered notice says, encouraging visitors to grab a few.

The Ripped Bodice opened last year. The sisters got their seed funding on Kickstarter, where they raised $91K in six weeks. (Anyone who donated more than $500 could receive a gorgeous quilt, handmade by Leah, with the words “FINE SMUT” appliqued on it.) The store’s philosophy, according to Bea, is “No blink, no blush: We are here to help you find what you’re looking for, without any kind of judgment or agenda.”

Its success seems like a no-brainer. Romance is the bestselling genre in America ($1.8 billion in sales in 2013) with the most committed readership; a recent Nielsen study found that 15 percent of its fans buy a book a week or more. And independent bookstores in general are on the rise, with a 27 percent increase in number since 2009. Amazon simply can’t deliver the customer experience Bea and Leah provide. But romance still gets little respect. “It’s a genre largely written by and for women,” Bea tells me with a look. “Some people are judgy. It’s just annoying.”

The girls both started reading early. “I loved anything about queens and princesses,” Bea says. “But it was because I loved women taking control of their own stories…and if they were royalty they could do that. Elizabeth the First kicked ass!” At around 12, she started reading historical romance. Leah chimes in, “I wanted to read what my older sister was reading, but I wasn’t into history. She thinks it’s cool and empowering and I’m all, uhh, that seems terrible?”

“In our house, you had to read. It wasn’t a choice,” Bea says. “But you could read whatever you wanted.” Leah adds, “We were barely allowed to watch TV. It was PBS, one hour a day.” (The sisters interrupt and complete each other’s sentences constantly. If I’d been interviewing them on the phone, I’d have had no idea which one was saying what.) “We were raised by a mother with the notion that reading is so important to being a good citizen, and an engaged citizen—reading was part of being a good Jew for her,” Bea says.

Their mom, Ellen Liebman, grew up in one of the few Jewish families in Frankfort, KY. “They had to drive to Lexington for temple,” Bea says. “She wasn’t super-religious, but Jewish traditions were very important to her, because she was a fish out of water. She had a hard time in Kentucky; she was not a Southern belle.” Denied a Bat Mitzvah as a child, she had one as an adult. As an undergraduate, she majored in religious studies, then became a lawyer, got a master’s degree at Yale Law School, and became a law professor. Then she had kids. “She wanted to be a stay-at-home mom, and she applied the precision of editing law papers to the precision of editing fourth grade essays about Lithuania,” Bea says. Her daughters attended religious school twice a week at Temple Sholom in Lakeview.

Ellen died of ovarian cancer in 2005, when her daughters were 16 and 13. The first sentence in her obituary in the Chicago Tribune read, “Ellen Liebman believed so strongly in the Jewish concept of tikkun olam, or repairing the world, she built her life around it.” Indeed, she served on the advisory board of the Chicago chapter of Facing History and Ourselves, a non-profit that uses the Holocaust to teach students about moral choice, and also on the board of Northwestern University’s Center on Wrongful Convictions. “She was super charitable,” Bea recalls. “She was in a book club. She wanted to raise well-educated, intellectually curious girls. For her, it was all concentric circles of being Jewish.” When Bea developed a Holocaust literature fixation as a child—“I read all the children’s books and then I went to our synagogue library and read everything there, and I read Mein Kampf at 14”—Ellen found a Holocaust historian who was willing to chat with her daughter to help her process. “I was a highly sensitive child,” Bea says.

Leah quit Hebrew School soon after her mother’s death; she now identifies as an atheist. “My mom died soon after my bat mitzvah,” she says slowly. “There was no way I was continuing.” (She has a tattoo of her mom’s signature on her foot.) Bea is less ambivalent. She’s writing a historical romance novel based on the life of Judith Montefiore (1784-1862), author of the first Jewish cookbook and a patron of arts and education.

The sisters live together as well as work together. “We had to be together. It’s sad,” Leah says, pulling a face. It clearly isn’t. The store is a family affair; the sisters’ dad and their cousin flew out for a week to help with construction, sending tools ahead of time. “See that wall?” Leah points. “My dad built that wall. I helped.”

“I am not allowed on ladders,” Bea says.

The Ripped Bodice donates books to the Downtown Women’s Center, an organization that works to end homelessness in LA, and sells a line of merch called Human is Human that donates 30 percent of profits to the ACLU. Fitzwilliam Waffles has his own line of notecards that benefit A Purposeful Rescue, the organization for hard-to-adopt dogs that saved him. “Our parents made it very clear: You have all this privilege, and have to give just as much back,” Bea says.

A sign outside the store notes:

LOVE IS LOVE

BOOKS ARE MAGIC

WE’LL BE OKAY

Bea and Leah make me believe that might be true.

Marjorie Ingall is a former columnist for Tablet, the author of Mamaleh Knows Best, and a frequent contributor to the New York Times Book Review.