Plan To Open Another Holocaust Museum in Budapest Faces Criticism—From Jews

Many worry it will be window-dressing for politicians who want to be seen remembering the Shoah but ignore today’s anti-Semitism

The Hungarian author György Konrád is arguably one of the best-known child survivors of the Holocaust. By a stroke of luck he narrowly avoided being deported to Auschwitz in 1944 along with the Jews of his hometown, Berettyóújfalu, in eastern Hungary. He, his sister, and two cousins survived the war in a Swiss-protected Budapest safe house. His parents, who had been deported to Austria, also survived and were reunited with their children in Berettyóújfalu after the war—the only Jewish family from the town to survive intact.

Yet in mid-December, Konrád, now 81, pointedly declined an invitation to take part in an advisory session for a new $22 million state-sponsored Holocaust memorial museum and education center focusing on child victims that is slated to open next spring. “It would be hard to shake the feeling that the hasty organization of this exhibition is not about the hundreds of thousands of children murdered 70 years ago, but rather about the Hungarian government of today,” Konrád wrote in an open letter to the museum’s director. “If the government wanted to devote such a large sum to the memory of these children, then in the spirit of the children’s spiritual heritage I would suggest they turn this amount over to feeding the badly nourished, living Hungarian children of today.”

Konrád’s words reflected the powerful mix of political, emotional, and ideological passions that the plans for the new complex have ignited in this sharply polarized country since they were announced in September by the nationalist Fidesz party government, headed by Prime Minister Viktor Orbán. The new institution is to center mainly on the experience of children during the Holocaust—but also on Hungarians who rescued Jews. It will be located in the disused Józsefváros train station in Budapest’s rundown Eighth District, once a teeming Jewish neighborhood, and will be called “House of Fates,” a name that harks back to Nobel Prize-winning author Imre Kertész’s novel Fatelessness, which narrates the experiences of a teenaged boy during the Shoah.

Construction work began Dec. 17, and the facility, which is to combine a permanent exhibit with an interactive learning center and other services, is supposed to open in April 2014. It will be the centerpiece of a nationwide effort to mark the 70th anniversary of the Holocaust in Hungary. Nearly 450,000 Hungarian Jews were deported to Auschwitz-Birkenau in the spring of 1944. Later, after the Hungarian fascist Arrow Cross seized power in October 1944, thousands of Budapest Jews were shot dead into the Danube River, and tens of thousands more were deported to other camps or sent on forced marches toward Austria.

The memorial year events, which include hundreds of commemorations, synagogue restorations, and other projects around the country are the latest in several steps taken by Orbán’s government aimed, at least in part, to counter what it says is an unfair image of Hungary as a racist, anti-Semitic country. In early October, for example, Deputy Prime Minister Tibor Navracsics told an international conference on anti-Semitism and Jewish life held at Hungary’s parliament building that Hungarians had to recognize their country’s own culpability in the Shoah. “We know that we were responsible for the Holocaust in Hungary,” he said. “We know that Hungarian state interests were responsible.”

Fidesz, which has a two-thirds majority in parliament, is not overtly anti-Semitic. But the government has angered Jews by doing little to curb a growing cult of memory around Fascist-allied figures such as Adm. Miklós Horthy, the nationalist regent who led Hungary into World War Two as an ally of Nazi Germany. Recent surveys have documented a rise in open anti-Semitism in Hungary, and the extremist Jobbik party, with an openly anti-Semitic and anti-Roma platform, is the third largest party in parliament, holding 43 of 386 seats.

Not surprisingly, almost all facets of the House of Fates project have come under fire—from its name, to its location, to its overall concept, which some fear could lend itself to a skewed interpretation of the Shoah. Critics of Orbán’s government, including many Jews, have dismissed the initiative as a cynical move aimed primarily at outsiders to prove that Hungary is not an anti-Semitic country while at the same time it fails to take concrete action at home. “There is no trust,” said Anna-Mária Bíró, the president and CEO of the Tom Lantos Institute, a public human-rights foundation whose executive committee is chaired by the daughter of the late Budapest-born U.S. congressman, who himself survived the Holocaust as a teen. “On projects like this you need trust.”

***

Budapest already has a Holocaust memorial center and museum, which was established by the government and opened to great fanfare in April 2004, on the 60th anniversary of the Holocaust in Hungary—and two weeks before Hungary joined the European Union. It was a first-of-its-kind institution in Hungary, and at the time, the then-director told me that its aim was to present the Holocaust “as a Hungarian national tragedy” and “an integral part of Hungarian history.”

The museum, located on Páva Street just outside the city center, comprises a modernistic building centered on a restored synagogue. It draws relatively few visitors, however. And when I visited in December, I found many of its exhibit’s interactive screens were not working. Wires were falling out of some of the headphones, and some of the lettering on signage was peeling off.

When the Páva Street center was built, critics—including prominent members of Hungary’s Jewish community—took issue with its goals, its concept, and even its location—not to mention with local political maneuvers involved in its establishment. As I wrote in an article at the time, they also faulted organizers for building the center too hastily, without first working out details of its scope and without public debate. The center in fact opened without its permanent exhibition installed.

Those arguments are echoed today in the debates about the House of Fates. So far, few details of the new museum’s exhibition content and education program have been made public. The historian Mária Schmidt, who is overseeing the project, told me in an interview at her Budapest office that these are still under development. But she said the target audience would be school groups and young people, and much of the exhibit, as well as the learning center, will be interactive. The aim, she said, would be to engage youngsters by telling the story of the Holocaust from the perspective of people their own age.

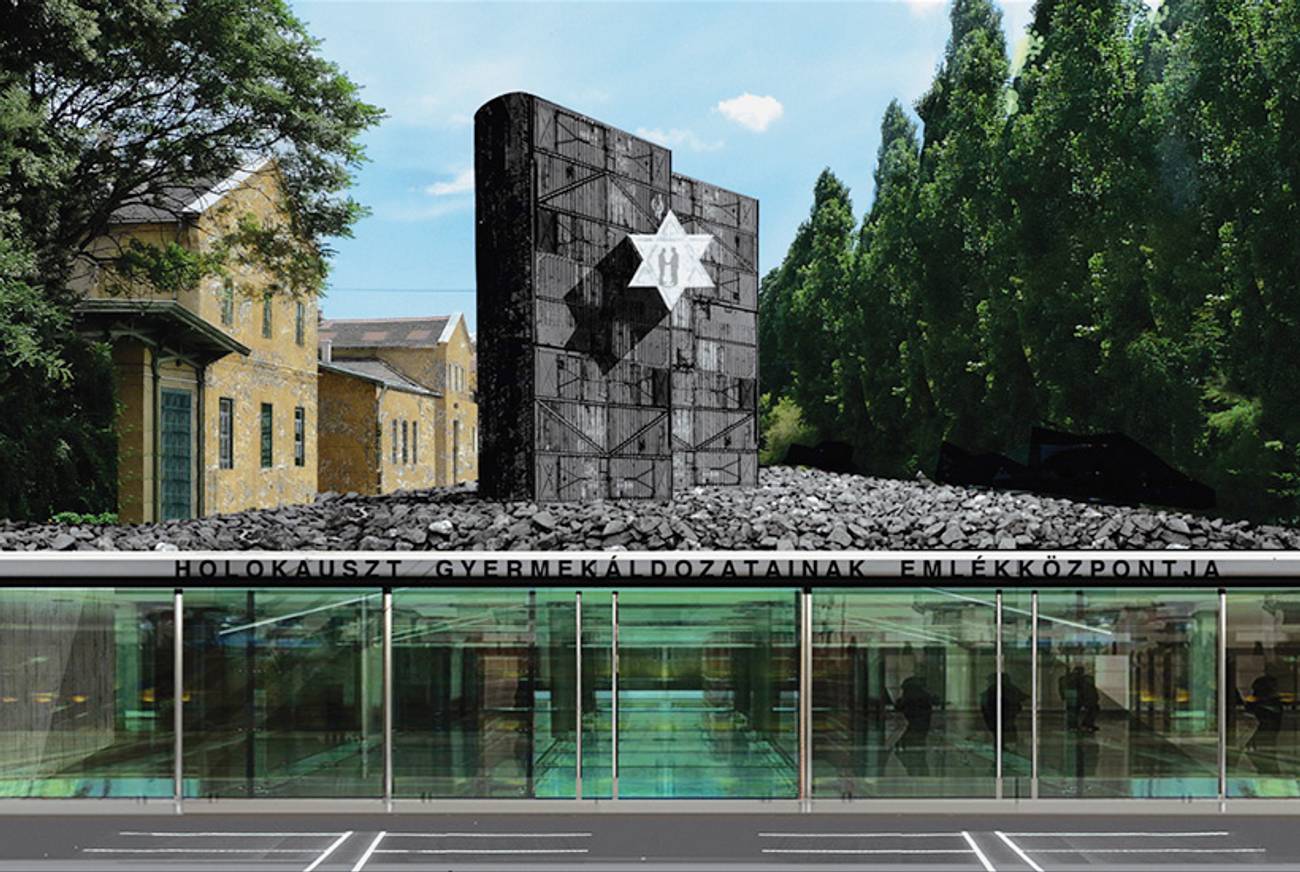

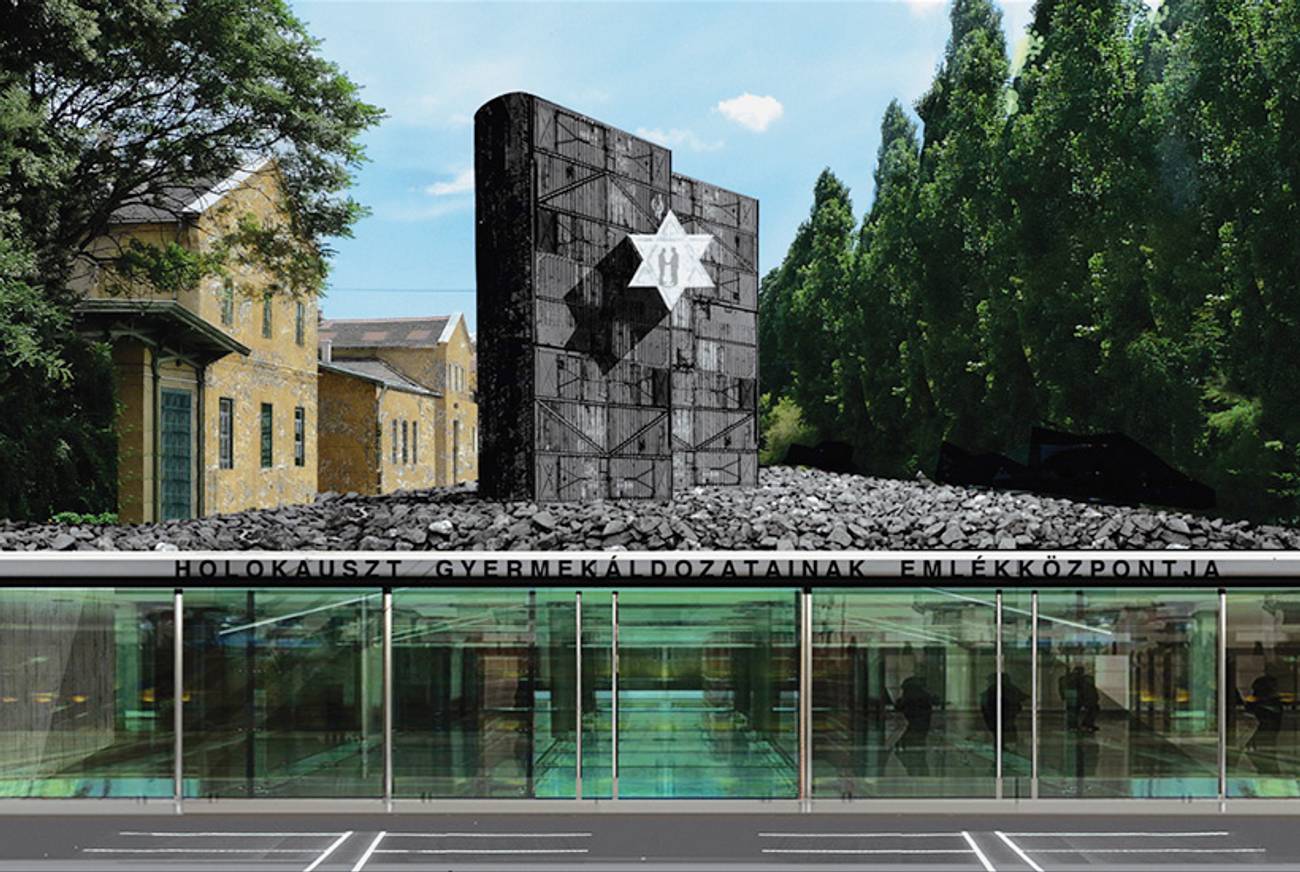

Site drawings for the complex show the exhibition and learning center located underground, entered through a wide glass wall. Rising above this space will be two tall towers made of railway freight cars, with a Star of David between them. The train station itself—which played little role in the mass deportations to Auschwitz but did serve later as a deportation point to other concentration camps—will retain its current exterior appearance, while inside it will house a café, shop, bookstore, and conference room. Schmidt said she recognized that it was unlikely that the project can be fully completed by April, but she said at least the physical structure and “main message” of the complex should be ready by then.

With the House of Fates, the selection of Schmidt to be the curator-director has raised some of the biggest questions, particularly among Budapest’s Jewish community. Schmidt is also the director of the House of Terror, another Budapest museum she developed, which focuses on the crimes of the Communist and Fascist regimes, and the name of the House of Fates implicitly also links back to that institution.

Critics have long assailed Schmidt, who is not Jewish, for minimizing the uniqueness of the Holocaust and putting the Nazi genocide of Jews on the same plane as postwar communist persecution. This is particularly evident at the House of Terror, a high-profile project of Orbán’s first government, which held power from 1998 to 2002. The museum, whose stark profile and exhibition were designed by the same architect now handling the new Józsefváros project, opened in February 2002 in a building that had been the headquarters of both Hungary’s WWII-era Fascist Arrow Cross movement and the postwar communist government’s secret police. The House of Terror, which draws between 200,000 and 300,000 visitors a year, equates the oppressive policies carried out by both regimes, but its powerful interactive exhibition devotes vastly more emphasis—and space—to the crimes of communism than to the annihilation of Hungary’s Jews, devoting just one of its many rooms to the Holocaust.

“The exhibit’s organizers say the museum is drawing crowds because it is one of the first attempts in Hungary to come to terms publicly with the difficult truths of the past six decades,” Thomas Fuller wrote in the International Herald Tribune in 2002. But, he added, “Critics of the museum—and there are many—say it is a political stunt. The curators, these critics say, are motivated more by contemporary politics than by a genuine desire to seek out historical truths.” He added, “Some of the criticism stems from the museum’s often slick presentation. Exhibits are so polished that history sometimes seems to be marketed rather than told straight.”

Some Jewish leaders fear that, with Schmidt in charge, the new Józsefváros Holocaust center will display similar problems and could end up distorting Hungary’s Holocaust history by placing all blame on the German Nazis, downplaying the role of Hungarians in the Shoah and stressing instead the role of Hungarian rescuers. “We have a problem [with] why Mária Schmidt is leader of this project, and … a lot of problems with the Terror House, particularly with its ideology,” András Heisler, the president of Mazsihisz, Hungary’s official Jewish umbrella organization, told me. “We are afraid of the impact that a very strong exhibition design could have.”

Those concerns aren’t limited to the House of Fates project: Mazsihisz also recently joined opposition politicians in criticizing plans announced Dec. 31 by the Orbán government to erect a memorial commemorating the Nazi occupation of Hungary. The statue is to be unveiled on March 19, the 70th anniversary of the occupation, in the downtown Szabadság, or Freedom, Square—where there already is a communist-era monument to Soviet soldiers. In a statement, Mazsihisz expressed “doubts and serious concerns” over the speed and manner in which the decision had been taken. Critics said such a memorial could further serve to downplay the role of Hungarian collaborators.

Heisler, who is a member of the new Holocaust museum’s advisory board, said he had proposed to Schmidt that Mazsihisz set up a local control team that could offer expertise and independently monitor the development of the exhibition on a regular basis. He said he gave her a list of 20 Jewish historians, archivists, rabbis, and leading intellectuals and asked her to choose five. By late December, Schmidt had not taken up this offer, but instead had invited a set of different Jewish intellectuals and experts to meet with her and offer opinions on the exhibition. This is the invitation that György Konrád, the writer, declined.

In a follow-up to our interview, Schmidt said in an email that “coordination with the Jewish community” was “in progress.” Among other things, she said, Giorgio Pressburger, a Budapest-born Italian writer who had been a child survivor of the Holocaust, had agreed to be her personal adviser on the project. Pressburger, who served as the head of the Italian Cultural Institute in Budapest from 1998 to 2002, grew up in the Eighth District, not far from the site of the new Holocaust center, and immortalized Jewish life in the neighborhood in some of his short stories.

The 12-member International Advisory Board, Schmidt told me when we met, was expected to convene in late February to “discuss and evaluate” plans. The board includes academics and intellectuals from Europe, the United States, and Israel, including representatives from Yad Vashem. “We should not conclude now that this project will serve Hungarian Holocaust revisionists, although this is a fear that has been frequently voiced,” board member Rabbi Andrew Baker, the American Jewish Committee’s director of International Jewish Affairs, told me. “I do not know how significant a role will be played by the International Advisory Board, but they are not people who would support such a direction.”

But ignoring direct input from Mazsihisz could set the scene for a potential stand-off with Hungary’s Jewish establishment and further sour Jewish attitudes toward the project—which are already mixed. “Politicians love something you can touch—buildings, monuments, museums,” said Eszter Lányi, a Jewish education and human-rights activist who served as the Hungarian cultural attaché in Israel from 2007 to 2011. “But I would rather see the government give 5 billion forint for living Jews, on education, rather than on dead ones. Everyone I talk to says the same thing.”

Editor’s note: This article has been updated to reflect that the late Tom Lantos was a member of the House of Representatives, not a senator. The Jobbik party currently holds 43 seats, not 47, in the Hungarian parliament.

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Ruth Ellen Gruber writes frequently about Jewish cultural and heritage issues and coordinates the web site Jewish Heritage Europe. Her Twitter feed is @ruthellengruber.

Ruth Ellen Gruber writes frequently about Jewish cultural and heritage issues and coordinates the web site Jewish Heritage Europe. Her Twitter feed is @ruthellengruber.