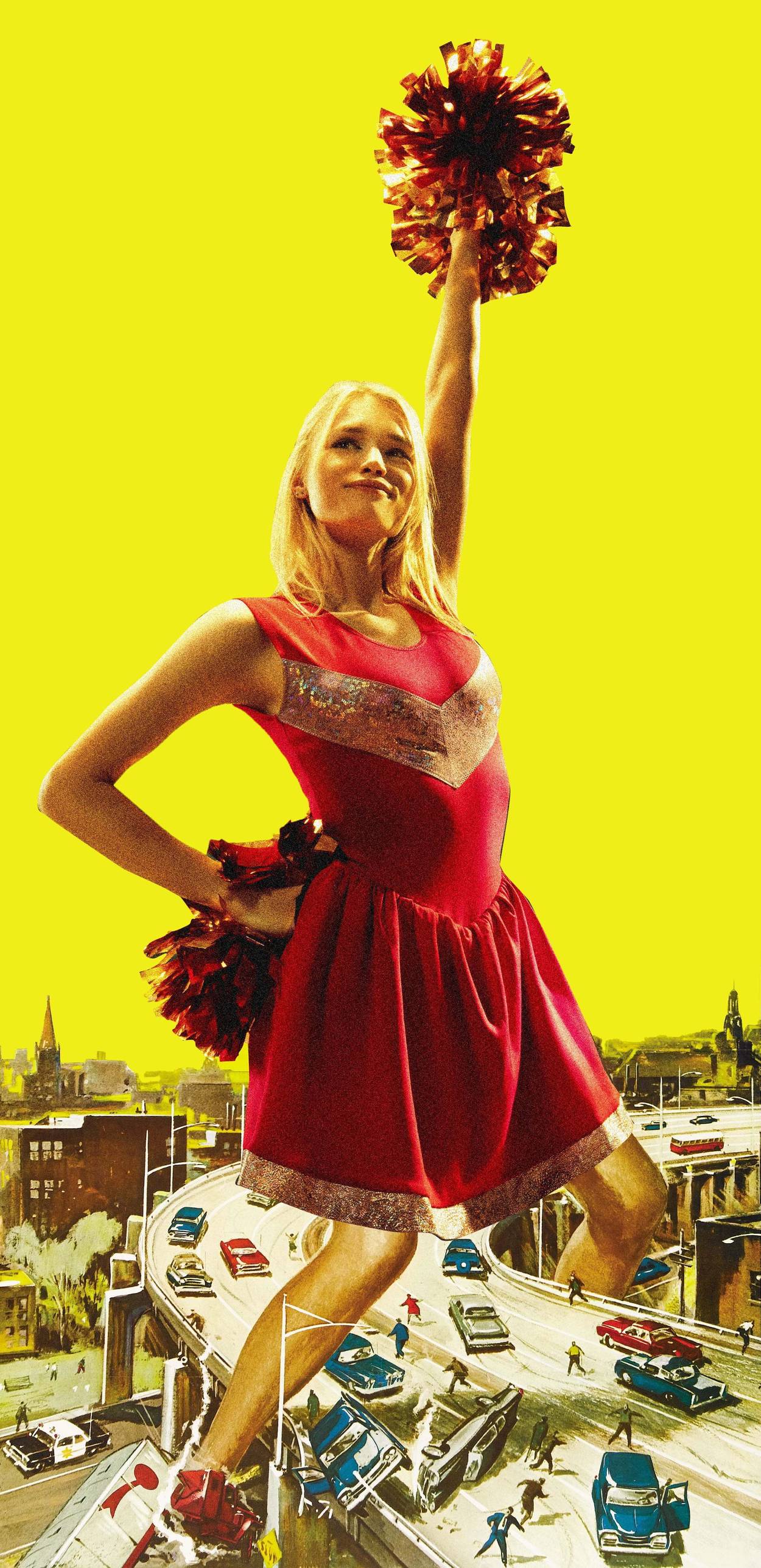

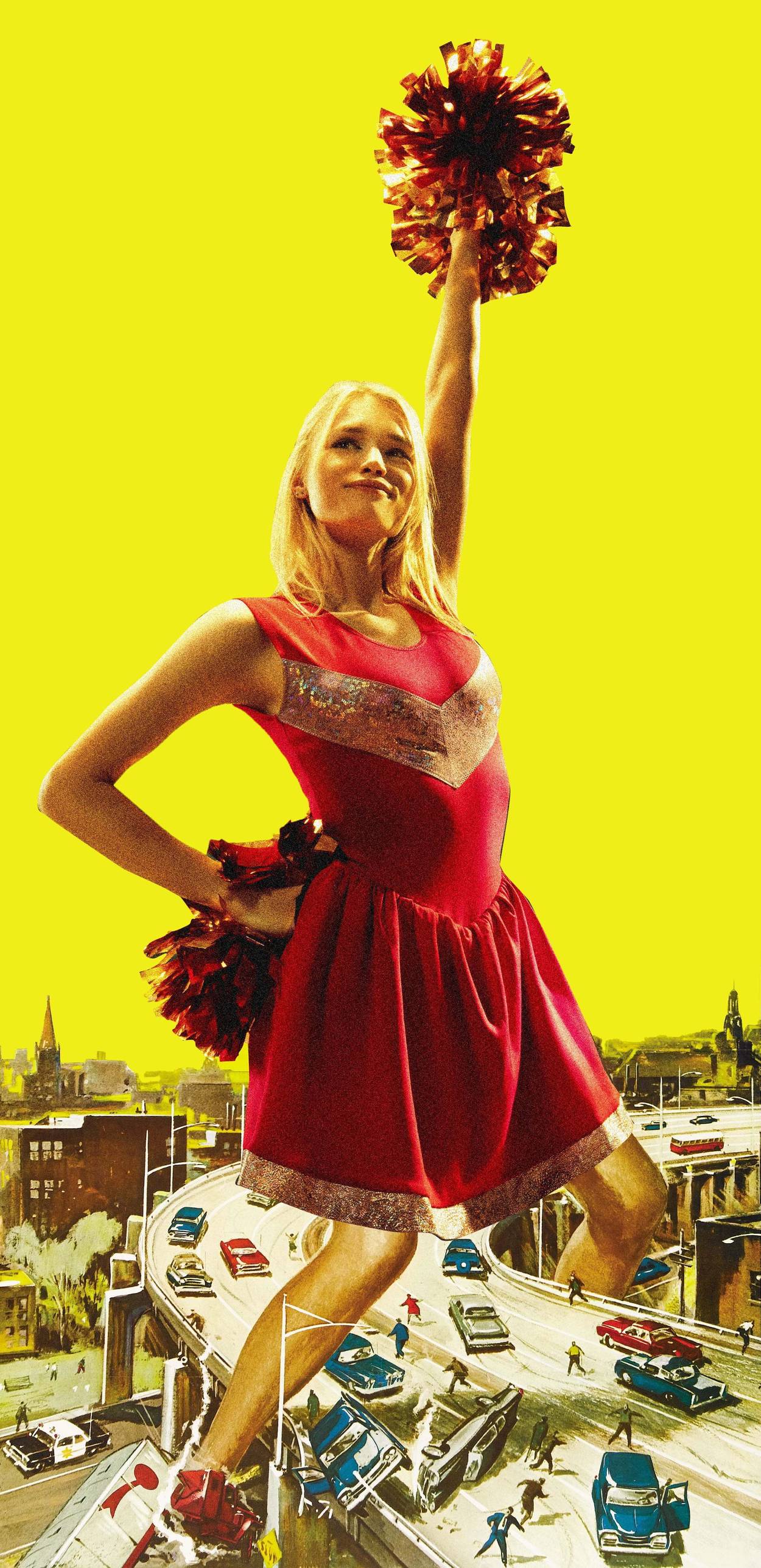

Watch Out for Big Cheerleader!

America needs more worker power, not more antitrust lawsuits

With his executive order on antitrust, President Joe Biden has aligned his administration with the anti-monopoly movement that has become influential in the Democratic Party in the past decade. Based on advocacy groups like Barry Lynn’s Open Markets Institute and Matt Stoller’s American Economic Liberties Project, the movement has achieved its greatest success with the appointment of one of its most brilliant members, Lina Khan, as chair of the Federal Trade Commission. Unfortunately, the anti-monopoly movement does not, and cannot, address the greatest crisis in American society: the widening divide between the country’s lawyering and opinion-making class and its working-class majority.

Some of the economic problems identified by the antitrusters are genuine. Conglomerate mergers, for example, are hard to justify. Why should a holding company like Alphabet own Google, Android phones, and Waymo, a self-driving car firm? The danger that the holding company’s deep pockets will allow its unrelated assets to compete with others below cost justifies the breakup of such conglomerates.

Monopolies or near-monopolies in essential economic infrastructure are also a concern. These can take the form of physical infrastructure like roads and bridges or firms upon whose services most businesses and citizens depend, like Amazon for retail, Google for online search, and Facebook for media. But in these cases, the solution to the problem is government regulation, not eight Amazons and 12 Googles.

If all you have is a chain saw, everything looks like a tree. Like their patron saint Louis Brandeis, the early-20th-century lawyer and Supreme Court justice, the new anti-monopolists believe in “the curse of bigness.” They make it clear that they want to break up everything big, simply because it is big. The Open Markets Institute, for example, published a study titled “Big Beer, a Moral Market, and Innovation.”

Jobs that last are created by small businesses that ceased to be small—at which point anti-monopolists want to punish them.

Then there is the threat of Big Cheerleader. No, that’s not a remake of the classic 1958 movie Attack of the 50 Foot Woman, but rather a reference to that great American economic crisis, concentration in the cheerleading industry. As Stoller explains: “This Is Not a Democracy, It’s a Cheerocracy: The Cheerleading Monopoly of Varsity Brands.”

Stoller is also alarmed that 64.2% of the American bagel market is controlled by a Mexican company with the delectable name of Grupo Bimbo. The backbone of America is small bagel companies! To save American democracy, we must break up Big Bimbo Bagel!

If Big Beer, Big Cheerleader, and Big Bagel are engaged in illegal price-fixing schemes, then by all means let Department of Justice lawyers try to break them up or win consent decrees. But apart from slightly reducing prices for beer and pompoms and bagels, how does all this litigation help American workers and families?

The anti-monopolists prefer to ignore the class divide. Or rather, like many conservatives, Democratic antitrusters identify “the people” with “small business owners,” or what Marxists call the petty bourgeoisie. The problem with equating the petty bourgeoisie with “the people” is that small business owners who hire workers are a tiny numerical minority in the United States.

True, according to the Small Business Administration, small businesses account for 99.9% of U.S. businesses. But the vast majority of these businesses are simply individuals who have incorporated for tax purposes and have no employees. Only around 6 million out of 31.7 million small businesses in total have one or more paid employees other than the owner-operator. What most of us might think of as small businesses—those with fewer than 20 workers—employ only 18% of the U.S. workforce. By contrast, more than half of American private sector workers are employed by firms with more than 500 employees.

While it’s true that small businesses create most jobs, they also destroy most jobs, because most small businesses fail in a few years. Most net job creation comes from firms like successful tech startups, which can rapidly scale up to become medium-size or gigantic firms. In other words, most new jobs that last are created by small businesses that eventually cease to be small—at which point the anti-monopolists want to punish them for their success.

Breaking up big firms would not lead to a job explosion as much as a rearrangement of existing jobs. Nor would it affect inequality much, if at all. Suppose you break up Facebook into five Baby Facebooks. Many of the same capitalists and institutional investors will own most of the stocks and bonds of the new successor firms. Moreover, the same sort of people from the same elite universities with the same mix of woke social liberalism and economic libertarianism will run most of the new Facebooks. All you will have done is rearranged a few seating arrangements at Davos.

But maybe—just maybe—anti-monopolism appeals so strongly to today’s Democratic Party and its media claque precisely because antitrust does not in any way threaten the vastly unequal American class system. With its financial base in Silicon Valley and Wall Street and its social base among the upscale, college-educated Americans who run almost all institutions, Democrats are increasingly the party of the corporate elite and its retainers in think tanks, law firms, and universities.

Unlike socialism or trade unionism, anti-monopolism does not question the neoliberal faith in the free market. That’s why “progressive” anti-monopolist organizations all sound like right-wing libertarian outfits, like the aforementioned Open Markets Institute and Economic Liberties Project. Like their philosophical cousins, the libertarians (who, unlike anti-monopolists, tend to be relaxed about antitrust), anti-monopolists profess a religious faith that the way to a better society is through freer markets. The solution to the ills of American capitalism is more capitalism. It must be!

What about the class divide? Some anti-monopolists have tried to integrate the neoliberal enthusiasm for antitrust with traditional liberal concern for wage earners by arguing that the “monopsony” power of large employers allows them to pay low wages, because workers have little bargaining power. This analysis is correct—a janitor has next to zero bargaining power with a large company. But the anti-monopolist solution—to pulverize the large company into several smaller companies—wouldn’t increase the bargaining power of the janitor much at all. Take it from me, the grandson of a janitor.

Even the economist and former Treasury Secretary Larry Summers, as pro-market a neoliberal mandarin as there is, scoffs at the left-wing anti-monopolist theory that attributes lower wages to increased business concentration instead of other factors like declining unionization. As Summers and co-author Anna Stansbury wrote in a 2020 study for the Brookings Institution,“[T]here is less direct evidence of a rise in labor market monopsony power … than there is of a fall in worker power. It does not seem plausible that monopsony power has increased as a result of an increase in labor market concentration.”

The approach of traditional liberals of yesteryear to the problem of low bargaining power was the exact opposite of antitrust: to build up the leverage of workers as a group relative to employers by means of what the economist John Kenneth Galbraith called “countervailing power.” Countervailing power can be wielded on behalf of all workers by government, which could impose a higher minimum wage. In addition, the power of firms to set wages, benefits, and work schedules as they prefer can be thwarted by the countervailing power of organized labor institutions, like trade unions and labor representatives on wage boards. Back when private sector labor was strong in the United States, union leaders tended to prefer big firms to small ones, because it is easier to negotiate with a few giants than with lots of Lilliputians.

The remnant of the labor left still promotes a living wage and unionization. But while today’s Democratic Party pays lip service to the goals of organized private sector labor, these are not serious priorities compared to climate change or race-and-gender “equity,” particularly among the party’s affluent managers and professionals, its trendy billionaire donors, and its foundation program officers. In a twist worthy of a satire, the professional-managerial class has in many cases successfully imposed its cultural politics on zombie unions whose working-class membership would no doubt have greatly preferred a living wage—a weird form of cultural appropriation that was achieved by using foundation grants, and by unionizing entry-level media jobs filled largely by the children of the elite, while nostalgically evoking the struggles of fading industrial unions.

Of course, there are good reasons why a real living wage or—even more radical—a family wage is not central to the college-credentialed overclass agenda. A living wage or family wage mandated by government would make nannies more expensive for affluent, two-earner professional couples (unless they’re already paying their nannies a sub-minimum wage off the books). And when it comes to collective bargaining, most culturally progressive billionaires and executives of Silicon Valley are no more enthusiastic about having to negotiate wages and benefits with union representatives than reactionary capitalists like Henry Ford were in the old days.

Talking about small business, like talking about race and gender, is an excellent way to avoid talking about class.

American progressives and their billionaire funders embrace anti-monopolism and race-and-gender “equity” because it allows them to change the subject to abstract statistical disparities among races and genders, instead of the class divide within them—a divide internal to each racial and ethnic group that is largely hereditary and promotes ever-greater inequality under the guise of meritocratic credentialism, modified slightly by reverse racism and sexism against non-Hispanic white and Asian American men who lack elite personal connections.

A court order to break up Big Cheerleader will not threaten America’s bipartisan oligarchy; it will merely proliferate the number of overclass CEOs by slightly increasing the number of companies, while rewarding lawyers with high fees and helping academics and think tankers pad their resumes. Nor will racial and gender quotas in college admissions, hiring, or corporate boards promote greater equality—a word the elite has discarded in favor of “equity.” Why? Because most or all of those hired to fill these quotas will be affluent, educated individuals, not the working-class women and men with a high school education or less who make up the majority of every race and both sexes in the United States.

Talking about small business, like talking about race and gender, is an excellent way to avoid talking about class. You don’t need to actually do anything for the multiracial working class like raise the minimum wage, or regulate excessive drug prices, or promote private-sector collective bargaining, or outlaw payday loan profiteering, or collect taxes. Just break up Big Cheerleader!

Michael Lind is a Tablet columnist, a fellow at New America, and author of Hell to Pay: How the Suppression of Wages Is Destroying America.