China’s Future Ain’t What It Used to Be

20 years after the Goldman report, the BRICS are floundering

In January, China’s National Bureau of Statistics made it official: After decades of fabulous GDP growth, the rate is now down to 3%. The culprit is Xi Jinping’s “zero-COVID” policy, plus ruptured supply chains and soaring energy prices. In the post-lockdown recovery, growth will of course bounce back, but not into the enduring double-digit rates prevailing since the 1980s, when China became the envy of the world.

To unearth the longer-term trends, look at the whole film, not just at single frames—and then beyond China at all those nations touted as winners in the global sweepstakes. A good starting point is Oct. 4, 1957, when the Soviets launched Sputnik, the first man-made satellite, into space. The shock reverberated around the world, never mind that the orbiter would burn up three months later. America was sinking and the USSR was soaring. Such projections have filled a small library by now. The theme is “the decline of the West and the rise of the rest.” But just as regularly, the doomsters have proven as reliable as weather forecasters.

The USSR never managed to outrace the U.S. Instead, it fell apart on Christmas Day 1991. But 20 years ago, its Russian heir was anointed, this time with a much-hyped scenario authored by a team of economists at Goldman Sachs. Like Sputnik, “Dreaming with the BRICS: The Path to 2050,” published in 2003, made waves around the world. As a paradigmatic example of predictions of Western decline, the report deserves rereading. It should sober up all clairvoyants, past and present.

Goldman’s futurologists spun out a mesmerizing tale. The BRICs—Brazil, Russia, India, and China—were on a roll. By 2040, they would outstrip the advanced economies of North America, Japan and the EU. So, onward and upward—if things go right. But they never do.

Like all such prophecies, “Dreaming” has not fared well. Today Russia’s GDP ranks just a shade above that of Italy, which has one-third of Russia’s population. Twelve years after releasing its report, Goldman closed its BRICS Fund after a loss of $700 million in assets. This marked the “end of an era,” according to the Financial Times, “in which the four developing economies appeared to be shaping a new world order.” Jim O’Neill, the Goldman team leader, recanted in 2021. “Brazil and Russia [are now] back to where they were 20 years ago. If it weren’t for China—and India, to some degree—there wouldn’t be much of a BRIC story to tell.”

Indeed. Retrace real historical GDP (with inflation and exchange rates factored out) from 2003 to the present. The G-7’s share of the global take dropped from 67% to 58%. The BRICS scored nicely by nearly doubling theirs from 13% to 24%. But look again. Today, Brazil (below zero growth) and Russia (ditto) are economic basket cases. India added 1 percentage point to its share, which is being eaten up in per capita terms because of explosive population growth. India’s per-person GDP ranks just above Zimbabwe’s. Only China leaped from 7% to 17% of the global economy.

China’s growth, though, has been dissipating as well, and the problem runs deeper than the damage done by “zero-COVID.” The causes are not fleeting. They grow out of an economic model of copying yesteryear’s fast risers, Japan, Taiwan and South Korea. Herbert Stein, economic adviser to Nixon and Ford, formulated this law: “If something cannot go on forever, it will stop.” China’s growth dropped from 14% in 2007 to single-digits in the 2010s—long before COVID.

Why can’t double-digit growth last? Behold the downward trajectory of East Asia’s Wunderkinder. Japan’s breathtaking growth ended in 1970, falling to 3% at the end of the decade and segueing into 20 years of stagnation. South Korea used to shine with double-digit gains; in the aughts it averaged around 3%. Taiwan excelled with nearly 10%—down to 4% by the 2010s. What is the lesson for all would-be prophets?

This trio had set the model for China’s “catch-up capitalism.” It comes in five parts: an export-first growth model, artificially depressed currencies, underconsumption, and overinvestment. Plus, a state on top pouring streams of cheap money into favored industries, which bred collusion and helped to keep out foreign competition. The strategy of the “Little Dragons” yielded phenomenal growth during their takeoff from humble beginnings. These always yield spectacular percentages. As an economy grows into maturity, the rate peters out—the richer, the slower. Germany, using a similar recipe, also grew by leaps and bounds when climbing out from the ashes of World War II. Its “economic miracle” is past history.

By midcentury, China will be the oldest big economy in the world, with an army of 350 million pensioners.

China ran with the model of East Asia’s early risers while ignoring its already visible flaws. Overinvestment, the brother of cheap money and underconsumption, comes with two curses. One is overcapacity. As one estimate has it, there are 65 million unsold apartments in China. Multiply that by an average of three persons per household, and you could house 200 million people with all the empty apartments in China—the combined total population of Germany, France and Britain. This misdirected capital could have been put to more productive use.

A second curse of overinvestment is an old acquaintance known as the law of diminishing returns. It states that each new unit of a production factor produces less. In everyday terms: Buy one tractor, and you double the yield; get two or three, and each adds less grain per acre. Five will run into each other and bring the harvest to a standstill.

Nor does the story end here, given China’s disastrous demographics. Beijing’s worst enemy is the steady decline of its working-age population, driven by plummeting birth rates. Also in January, China went past the tipping point, reporting negative population growth for the first time in 60 years—a loss of 850,000 inhabitants. By midcentury, China will be the oldest big economy in the world, with an army of 350 million pensioners who don’t produce but soak up ever more social support resources.

Welfare leaves less for warfare while Beijing keeps arming itself furiously to topple the U.S. from its geopolitical perch, starting in the western Pacific. Among the world’s large industrial nations, the U.S. will be the second-youngest after India. “Young” translates into “productive.”

A shrinking labor pool raises wages, which eats into China’s competitive advantage as the “factory of the world.” Nor is this startling news. As early as 2012, a Boston Consulting Group study did the math. “In 2000, factory wages in China averaged just 52 cents an hour, a mere 3 percent of what U.S. factory workers earned. Since then, Chinese wages and benefits have been rising by double-digits each year, averaging increases of 19 percent from 2005 to 2010. The fully loaded costs of U.S. production workers rose by less than 4 percent annually.” To boot, productivity is lagging behind labor costs, dropping from a 10% increase in 2010 to 6% just before the pandemic. It is expected to fall for the rest of this decade, according to S&P Global Ratings. So, offshore manufacturing comes home or wanders off to low-wage economies, presently in Asia and tomorrow in Africa.

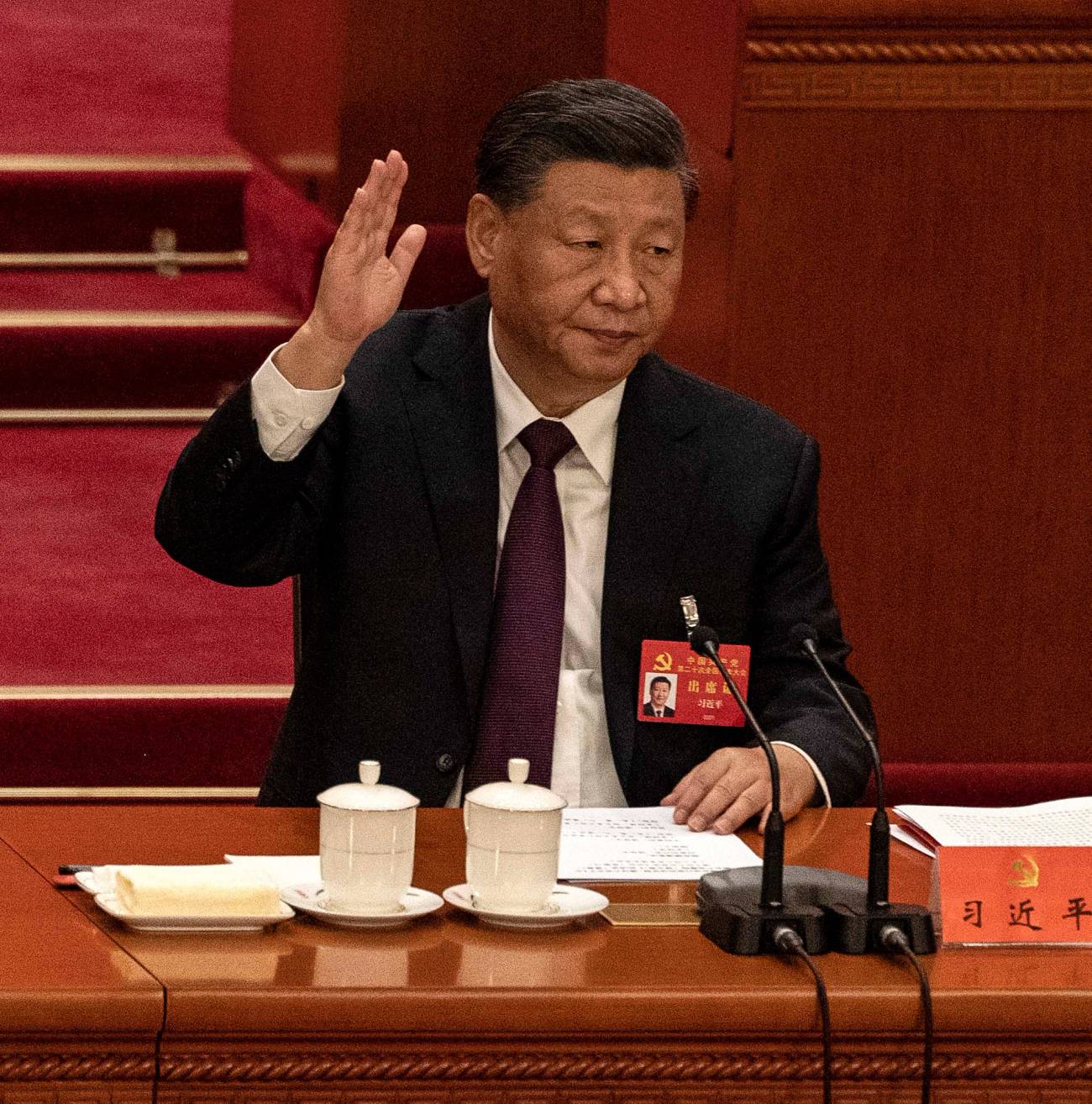

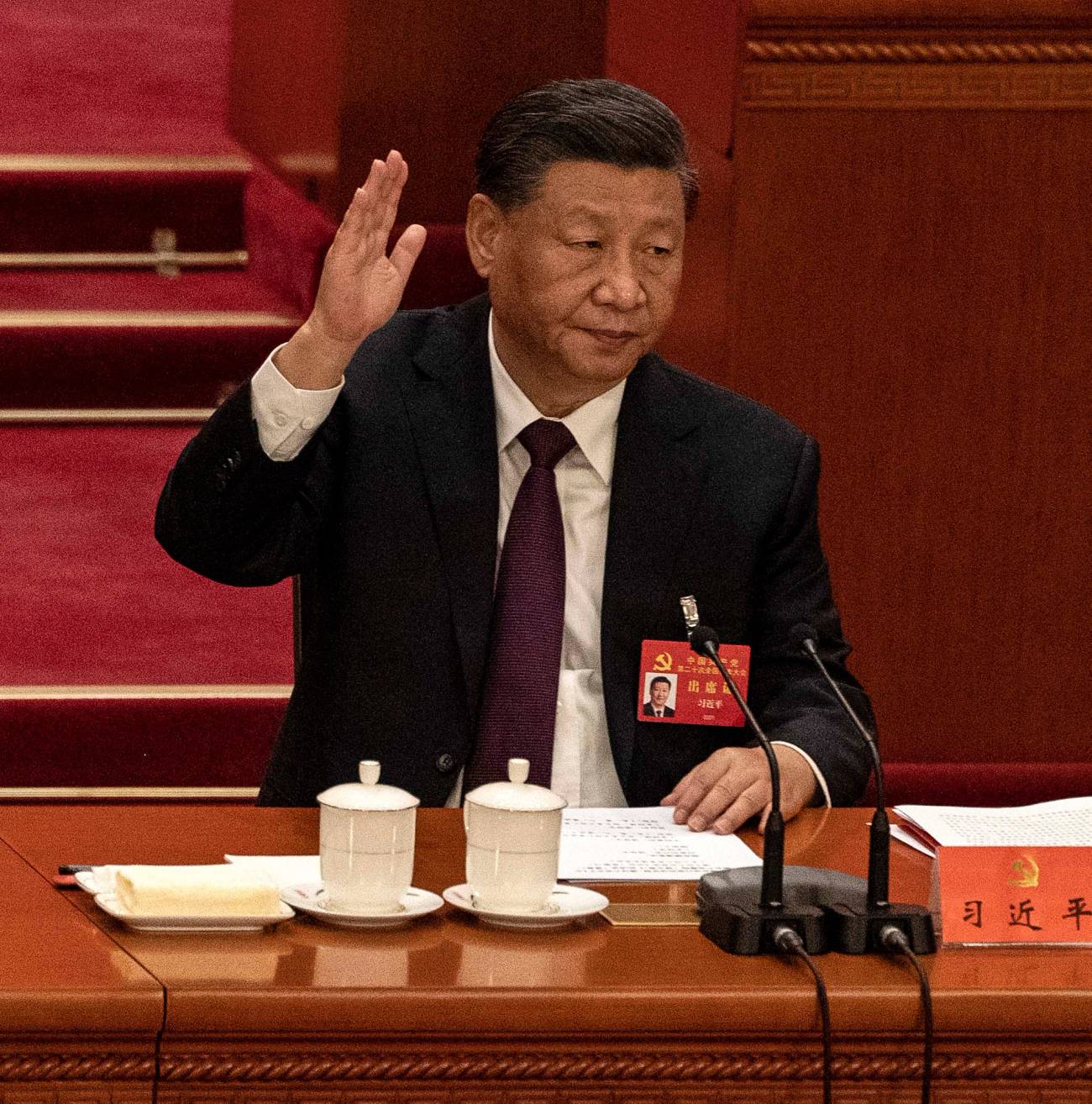

Let’s shift from statistics to the politics of Xi Jinping, leader for life. In the late 1970s, Deng Xiaoping had invented “Sinocapitalism,” triggering stunning growth. The party loosened its heavy grip in favor of cultural freedom and entrepreneurial autonomy, the unwritten motto being, “enrich yourselves, but leave the driving to us!”

Deng thought that growing wealth would keep the masses in line. Under Xi, hogging the wheel ever more tightly beats the national weal. Unleashed capitalism is yielding to a perfect surveillance state that demands obedience and denies initiative. The private sector is shrinking in favor of lavishly funded state-owned enterprises (SOE), which add less value than private firms, stifling efficiency and innovation. So, the puzzle: Why would Xi strangle the golden goose?

Since Lenin, Western sages—think George Bernard Shaw or Jean-Paul Sartre—have fallen for what I call “modernitarianism” as the fastest path to development. The state, they believed, was better than the market, delivering both wealth and equality. They kept missing the point. In the clash between power and profit, power wins. Even assuming that Xi’s henchmen had told him the truth about “zero-COVID” as an economy killer, why would a despot care? When reality knocks, control comes first, suppressing real-time feedback. Until very recently, Beijing methodically suppressed the horrifying COVID data.

Vladimir Putin keeps pillaging Ukraine, and never mind his sinking economy. His underlings will not risk their careers by confronting him with the bad news on and off the battlefield. In the sloppy, anarchic West, corrective feedback is built-in, and free markets don’t lie—they are the best information systems governments have. It is an iron law: The more concentrated the power, the less nations can adapt to economic ruptures. Five-year plans don’t allow for speedy revision.

Democracies cannot squelch dissent; that is their enduring advantage over the authoritarians. In crisis, strongmen invariably resort to suppression, which is good for them but bad for the economy. Repression does not increase returns, as the experience of all autocrats shows, most recently in Venezuela, Iran, and Russia. Xi’s China is looking at a similar fate. When power rules, growth falters.

The prophets who keep announcing the decline of the West and rise of the rest should recall Yogi Berra, who once quipped: “It’s tough to make predictions, especially about the future.” As to China, a slightly amended Yogism would be right on target: Its “future ain’t what it used to be.” Diviners beware. Leave prophecy to the Isaiahs and Jeremiahs.

Josef Joffe, a fellow of Stanford’s Hoover Institution and former editor of Die Zeit, teaches international politics and security at the Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies in Washington.