Chosen

Working on a book about the United States and Israel, we learned to stop worrying and love the idea of divine election

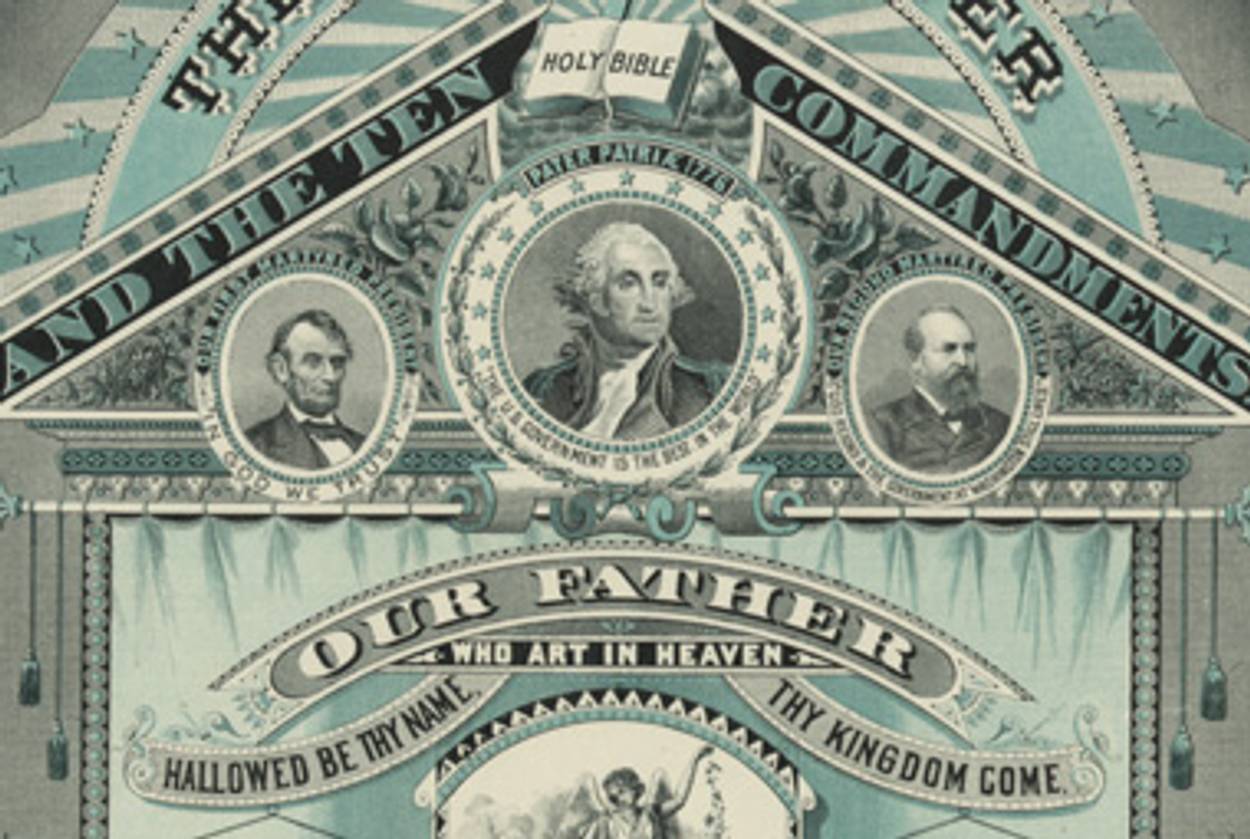

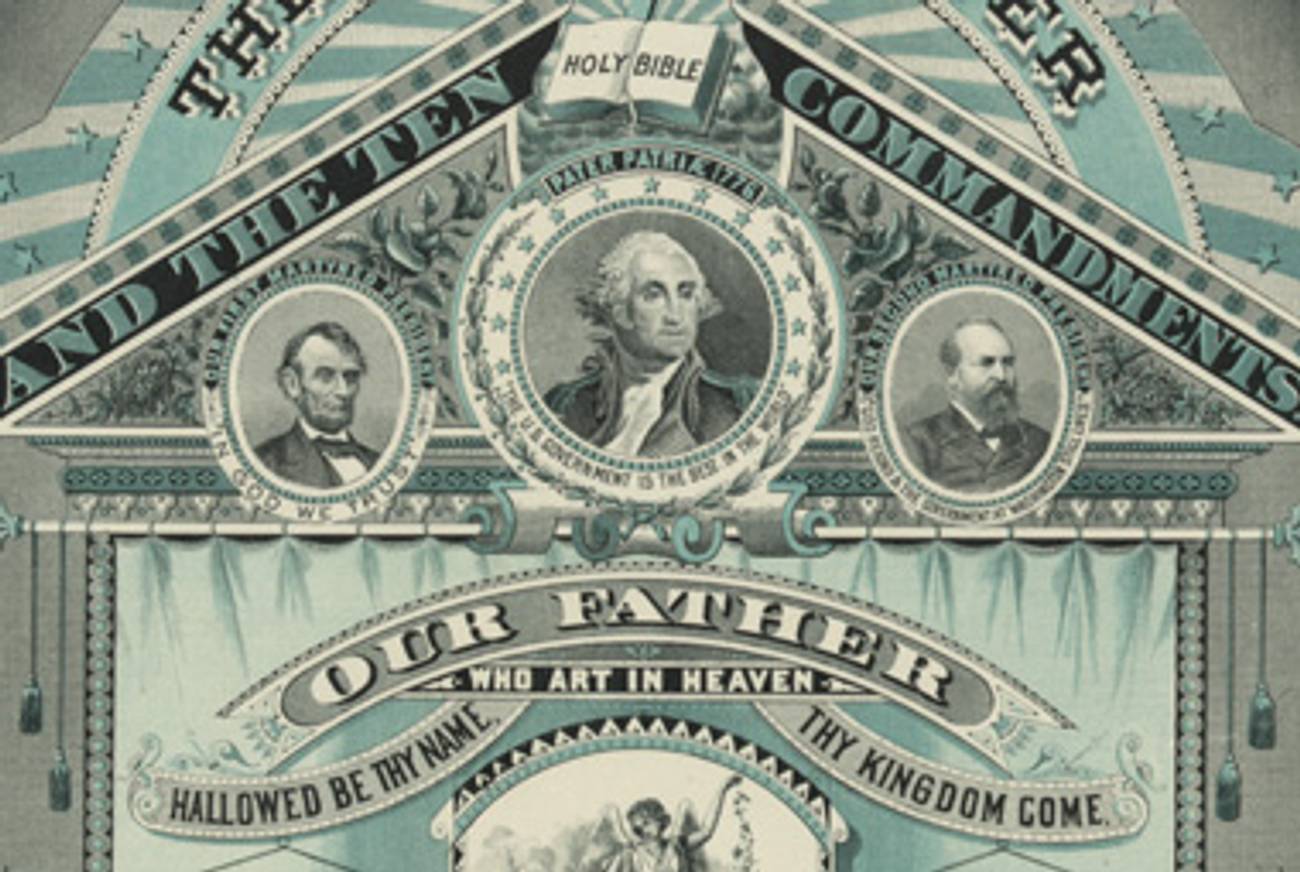

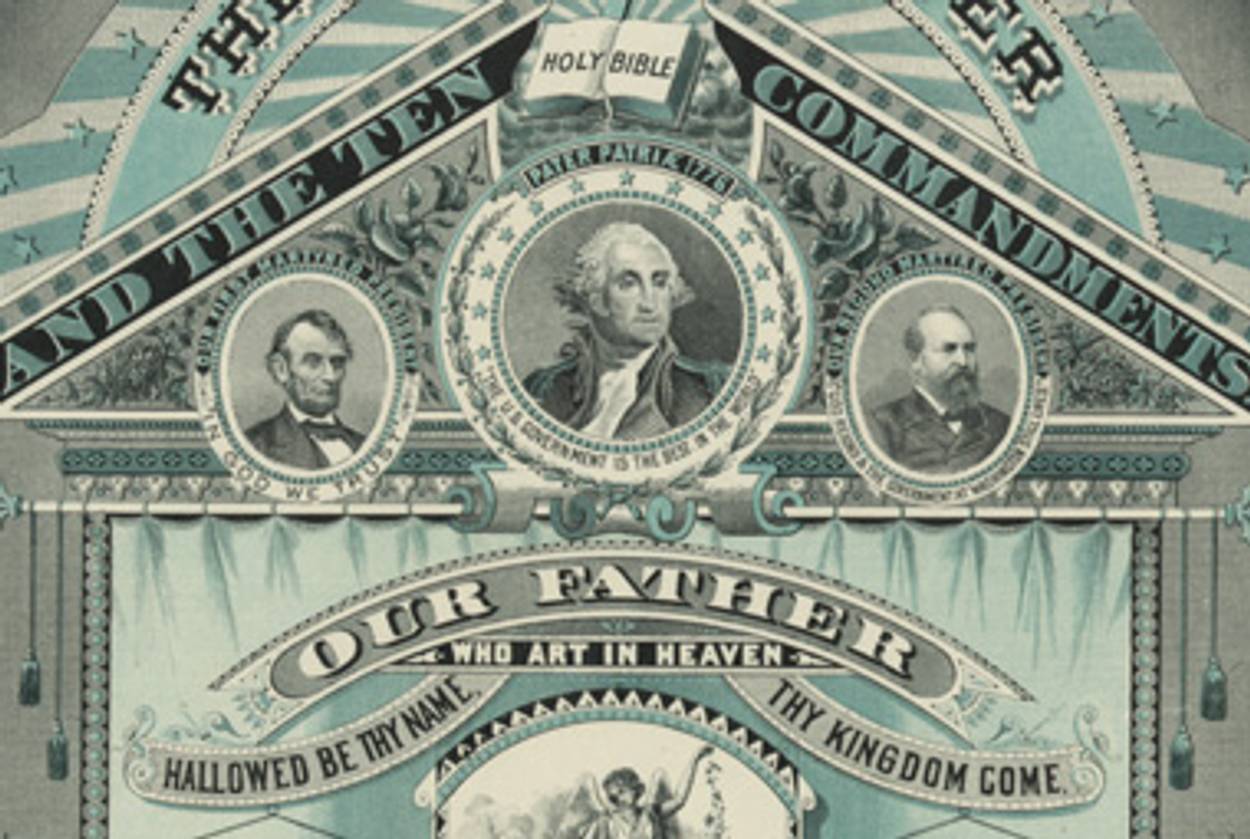

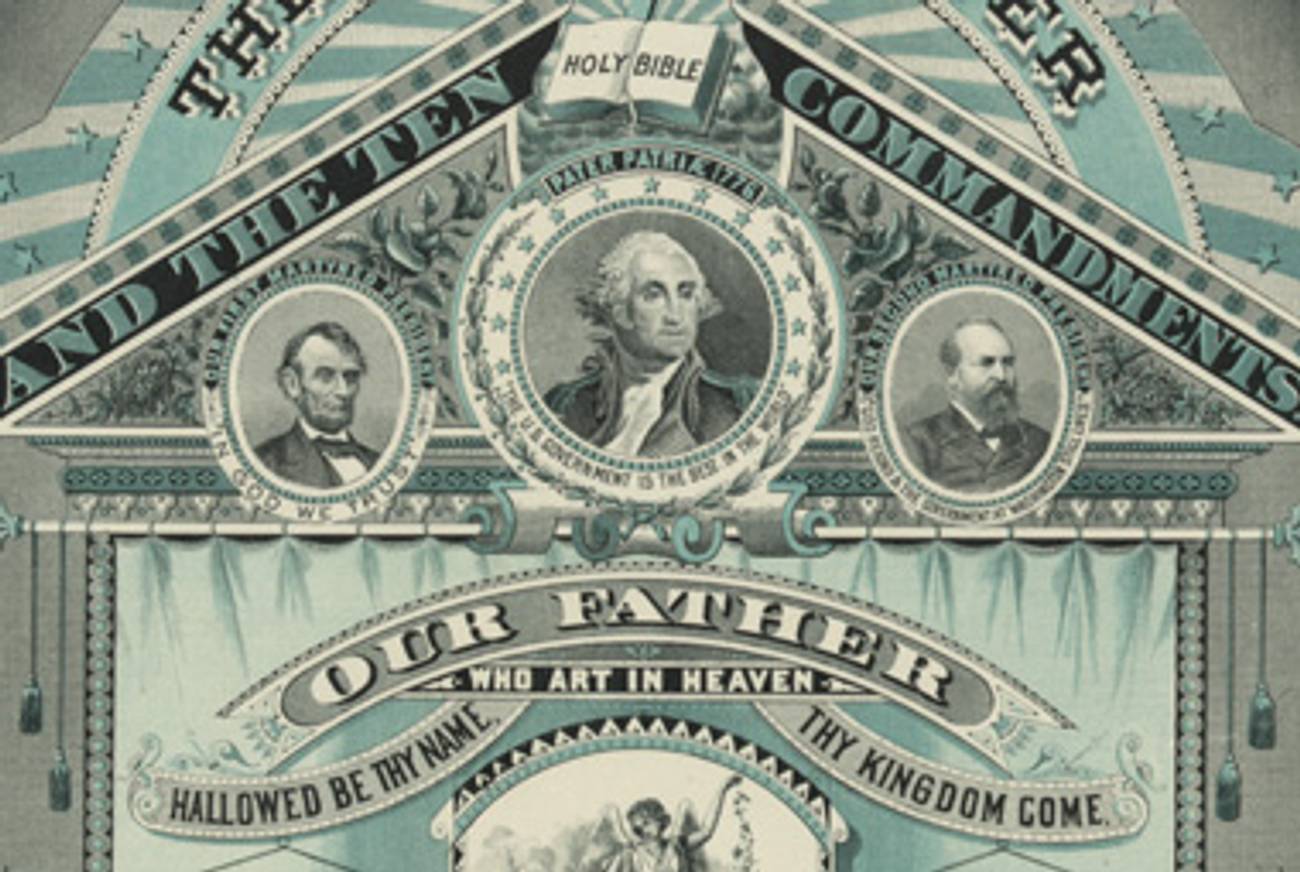

Two years ago, when we set out to write a book about Israel, America, and the ways in which the nations saw themselves as having been singled out by God to shine their light on a benighted world, we had little doubt about what kind of book we wanted to write.

Following the great thinkers of the Enlightenment—Kant, Voltaire, Bob Dylan—we thought that the notion of God being on any one particular nation’s side was wild or, worse, dangerous, the sort of Manichean delusion that could only drive people to hatred and violence. As longtime advocates of progressive causes—Todd as president of Students for a Democratic Society in the early 1960s, Liel as an activist in Israel’s peace camp in the 1990s—we preferred the porous and inclusive conceits of universal humanism.

And then we sat down to study.

Reading volume upon volume of Jewish and American history and theology, several things became clear to us. The first, and most stunning, had to do with the notion of chosenness itself. Rather than an inherently arrogant invitation to exceptionalism, we realized, the idea of chosenness is a profound and perplexing mystery; and it has long been understood as such in the Jewish tradition.

At the pinnacle of the biblical drama—as the Israelites gather at Mount Sinai, awaiting their transformation from a gaggle of tribes into a nation—God delivers a cryptic command: “You will be for me a kingdom of priests and a holy nation.”

The crowds congregated below are left to wonder just what he means. Why, the chosen people may be forgiven for asking, were we chosen? And what are we to do now that we’ve been singled out? How is a holy nation different from any other nation? Is the covenant with God eternal, or must it be renewed with each generation?

God, of course, doesn’t say. He leaves the Israelites wondering, and not only them: As we read the ancient text, we are invited to wonder anew for ourselves. If we’re honest, the one thing we can say for certain is that chosenness binds those who believe in it—or pride themselves on belonging to a people founded on the principle that they were divinely elected—to wrestle with the immense question of what it means to have been chosen.

This is no vicious circle. Wondering what it means to be chosen, we’ve come to believe, can be a noble if arduous path toward moral clarity. Consider the original chosen one, Abraham. A man of no particular distinction, he is so baffled by the divine attention lavished on him that God has to address him no fewer than five times, each time repeating variants of the same promises and assurances. Abraham struggles mightily with the sheer magnitude of his newfound heavenly favor. Eventually, he rises to the occasion, haggling with God to save the sinning cities of the plain. Rather than assume that God’s graces allowed him the right to behave as he pleased, Abraham labors to be found worthy of his singular good fortune. First he is chosen, and later he proves himself worthy. This is the majestic logic of divine election, and it is a powerful engine of compassion, justice, and human improvement.

While we found similar moments of transcendence shining throughout the course of American and Jewish history, we are not naïve about the many examples to the contrary. For every Lincoln, who urged America to live up to its divine designation, there was a Reagan, who emptily boasted of its might, and for every Maimonides—who argued that the Jews were not the chosen people but the choosing people, the people who elected to accept God and his laws—there were handfuls of militant, messianic zealots who considered the covenant a license to kill. Chosenness, we came to understand, could be interpreted in many ways but not ignored; we must learn to wrestle with it because, behind our backs, it is wrestling with us.

Never has it been more urgent for Jews and Americans to consider what we are called upon to do. Both nations, under fire, would do well to look to their fundamental commitments. The majority of Israelis want neither a territorially obsessed theocracy nor an utterly secular state stripped of its Jewish characteristics, just as the majority of Americans reject both mindless chauvinism and vicious, ignorant assaults. The way out of our predicaments is further in. If both nations grapple long and hard with the idea of divine election—as Abraham did, as Lincoln did—they might find a renewed sense of urgency and an invigorated pride.

It won’t be easy, especially for those who, like us, were brought up to look with jaundiced eyes on what happens when the fire of religion burns into the rational realms of democracy. But we believe—devoutly—that the idea of chosenness can serve us well: not as a divine mandate but as burden and responsibility, not just as our past but as our future as well.

Todd Gitlin and Liel Leibovitz are the authors of The Chosen Peoples: America, Israel, and the Ordeals of Divine Election. They’ll be speaking at the 92nd St Y on Monday, September 27, with Tablet’s editor-in-chief Alana Newhouse and contributing editor Jeffrey Goldberg.

Todd Gitlin (1943-2022), was a professor of journalism and sociology and chair of the Ph.D. program in Communications at Columbia University, and the author of among other books The Sixties: Years of Hope, Days of Rage; Occupy Nation: The Roots, the Spirit, and the Promise of Occupy Wall Street; and, with Liel Leibovitz, The Chosen Peoples: America, Israel, and the Ordeals of Divine Election.

Liel Leibovitz is editor-at-large for Tablet Magazine and a host of its weekly culture podcast Unorthodox and daily Talmud podcast Take One. He is the editor of Zionism: The Tablet Guide.