Closing In on the Classified Cover-up

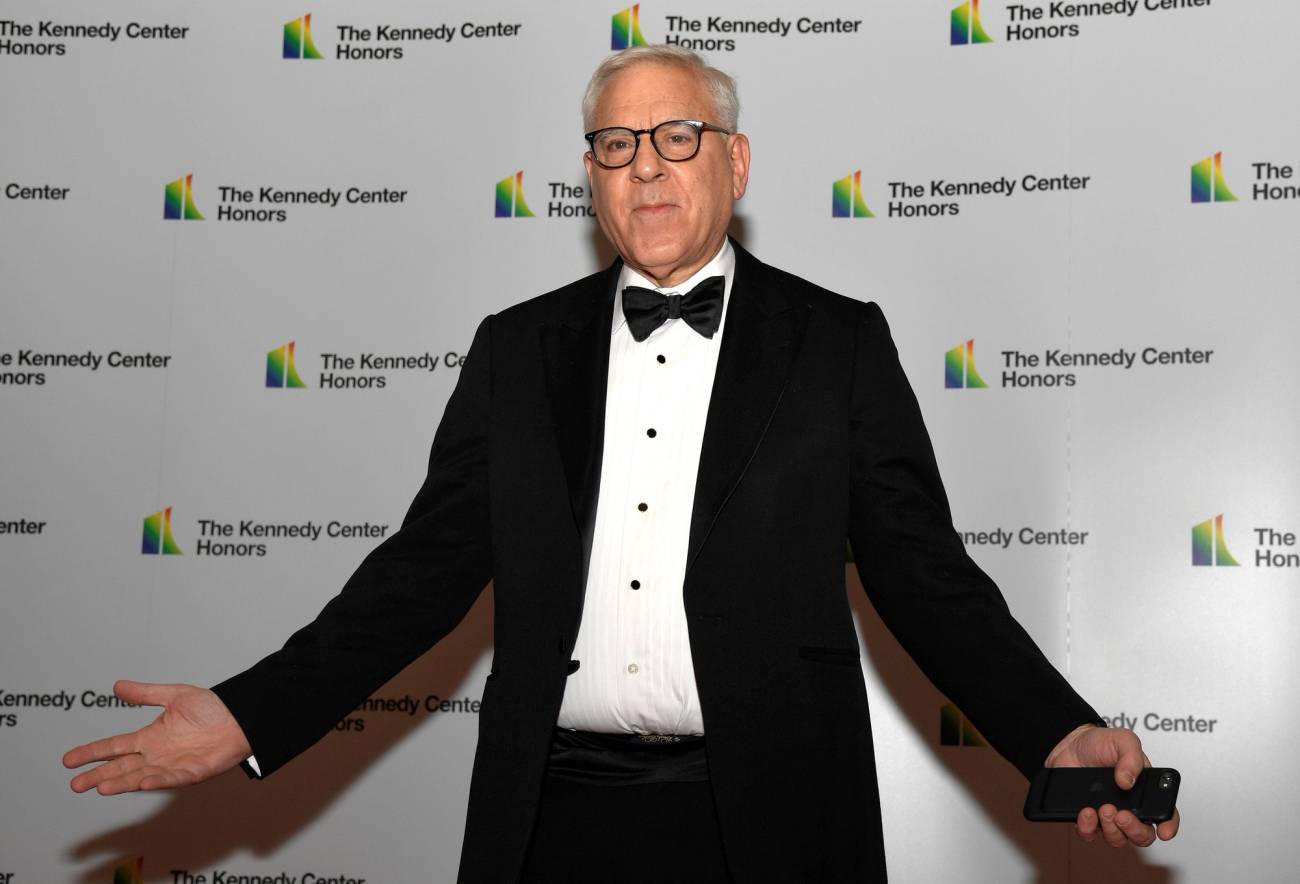

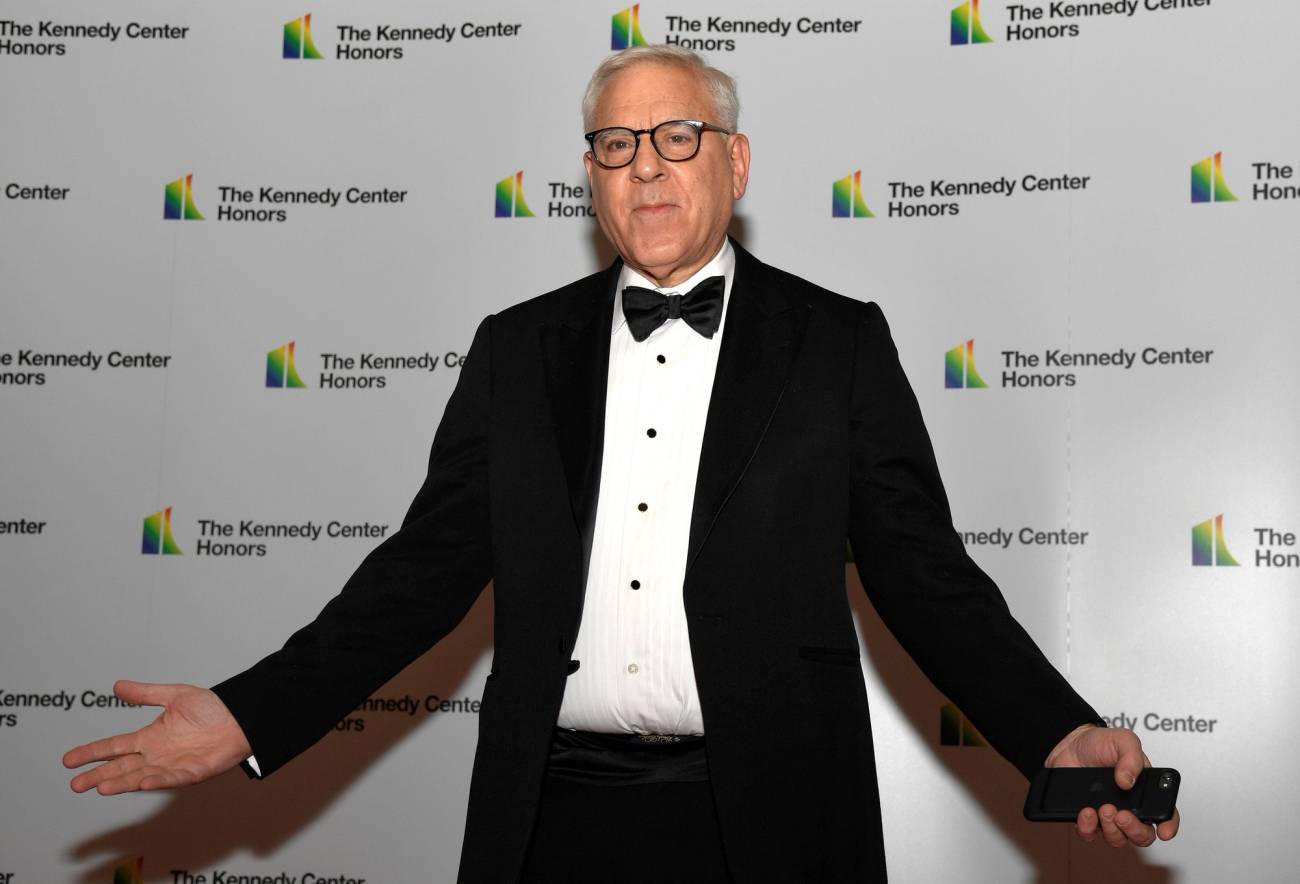

A major Biden ally is also a top donor to the National Archives. Could private equity billionaire David Rubenstein hold the key to the White House documents scandal?

At the center of the Biden document cover-up is the question of who blocked the National Archives and Records Administration from informing the U.S. public about the classified records found in the president’s office in early November. The archives’ general counsel told members of the House Committee on Oversight and Accountability that he couldn’t divulge that information, but GOP House leadership concluded that only Attorney General Merrick Garland or Biden himself could have given those orders.

But there’s a third powerful name in play, this one from outside of the government: David Rubenstein. Co-founder of the Washington, D.C.-based private equity firm the Carlyle Group, Rubenstein is one of the archives’ most generous patrons. In 2013, the David M. Rubenstein Gallery at the National Archives was completed at a cost of $13.5 million. Rubenstein is also a major Biden ally. He has regularly hosted the Biden family at his Nantucket estate for Thanksgiving—in 2022, 2021, and 2014.

According to the chairman of the GOP-led House Oversight Committee James Comer, the archives’ “inconsistent treatment of recovering classified records held by former President Trump and President Biden raises questions about political bias at the agency.” And, indeed, under recently retired chief archivist David Ferreiro, the archives gladly joined forces with the Department of Justice-led anti-Trump campaign. As Trump’s lawyers were negotiating last winter with archives officials over which documents constituted presidential records and which were personal, Ferreiro, his tenure winding down, struck his final blow for the resistance: He referred the former president to the DOJ for a criminal investigation that led to the FBI’s August raid of Trump’s Florida home.

For Americans wondering why, in contrast to its partisan activism last summer, the National Archives has suddenly gone silent during the Biden affair, Rubenstein’s patronage may offer a clue. A spokesperson for Rubenstein said he played no role in this matter and a spokesperson from the National Archives responded that they have no comment.

Indeed, Biden’s friend Rubenstein appears to exercise considerable influence over the staffing of senior personnel at the agency. Before Ferreiro was appointed by Barack Obama in 2009 to lead the National Archives, he was the university librarian and vice provost for library affairs at Duke University from 1996 to 2004, at the same time that Rubenstein was chair of the Duke Board of Trustees. The nominee to replace Ferreiro at the archives, Colleen Shogan, is also affiliated with Rubenstein. She is currently the director of the David M. Rubenstein Center at the White House Historical Center.

The National Archives is supposed to be above the political fray, an institution dedicated to preserving historical records. And indeed history is one of Rubenstein’s passions. According to one profile focused on his funding of Washington, D.C., monuments and institutions, “Rubenstein has shaped the cultural landscape of the nation’s capital perhaps more than any other private citizen in the past century.” It seems that Rubenstein’s historical mission is to turn U.S. institutions into platforms to promote contemporary progressive ideas. He donated $20 million to refurbish parts of Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello home in a makeover that recasts the founding father’s legacy as an object lesson in systemic racism. Ibram X. Kendi’s titles are available for purchase at the David M. Rubenstein Visitor Center, and the permanent David M. Rubenstein exhibit at the National Archives, “Records of Rights,” focuses on America’s disenfranchisement and mistreatment of minorities.

Like other top Biden allies, Rubenstein has long been bullish on the Chinese Communist Party. “China has a very bright economic outlook,” Rubenstein told a Davos audience in 2022. “We will continue to invest there.” A 2019 Wall Street Journal report showed that Rubenstein’s Carlyle Group helped Beijing evade U.S. export controls to purchase satellites that help network People’s Liberation Army troops, boost CCP propaganda broadcasts, and allow Chinese authorities to put down protests in Xinjiang, where the party has detained more than a million Muslims, mostly from the Turkic-speaking Uyghur population, in forced labor and reeducation camps.

Last week, the FBI conducted another inspection of one of Biden’s residences, this time a seaside home in Rehoboth Beach, Delaware, in an unsuccessful search for more classified documents. The president’s lawyers are at pains to emphasize that in contrast to the former president, whom Biden targeted for holding classified documents, the current commander-in-chief is cooperating with federal investigators. Despite the fact that both Biden and Donald Trump are under investigation for the same thing, it’s true that the two cases are different.

In Trump’s case, Merrick Garland appointed a special counsel because the White House wants to charge the frontrunner for the 2024 GOP nomination. The job of the special counsel assigned to the Biden affair is, it seems, to bury it. That’s why the Justice Department is ignoring the demands of Republican-led congressional oversight committees that want to know the substance of the Biden documents. Since those records are now part of an ongoing investigation, it’s unlikely the American public will see them anytime soon, or ever. And yet the scandal continues to grow.

For Americans wondering why, in contrast to its partisan activism last summer, the National Archives has suddenly gone silent during the Biden affair, Rubenstein’s patronage may offer a clue.

Thanks to the stonewalling from government officials, the public still knows very little about the nature of the original misdeed, but current and former Republican officials say the National Archives may be the origin point of the Biden affair. While the administration’s official account holds that the Biden documents were packed up and shipped to his homes and office when he left the vice presidency, congressional sources believe that he may have retrieved them from the archives after he left office. Those sources call this the “Berger scenario,” after Bill Clinton’s national security adviser, Sandy Berger, who was caught leaving the archives with classified documents in 2003. One recent press account shows that Biden visited the archives in early 2017. “When he was writing a book after leaving the Vice Presidency,” according to The Washington Post, “he made the trip to the National Archives to review relevant documents.”

Republicans are angry that yet another Biden scandal was hidden from U.S. voters before an election, but there were signs something was brewing shortly after the classified documents were first identified by Biden’s lawyers at his office at the Penn Biden Center in Washington, D.C., just before the midterms. According to the Biden team’s account, the White House notified the archives on Nov. 2 and the archives told the DOJ two days later. Less than two weeks after that, a Nov. 14 article in The Washington Post explained that, according to “people familiar” with the Trump investigation, officials believed that Trump’s decision to hold on to documents after leaving office was motivated by ego, not profit. He just wanted to keep mementoes he’d collected during his time as leader of the free world.

It was a remarkable reversal after three months of media hysteria that reached a fever pitch when broadcast celebrities accused Trump of selling nuclear secrets to Saudi Arabia, a crime for which, suggested historian Michael Beschloss and former CIA chief Michael Hayden, he should be executed. But never mind, what Trump had done wasn’t actually all that bad—because, as the U.S. public would soon learn, Biden had done the same.

And when the news did drop, party operatives brushed it off. The real problem, according to Biden boosters, is that the government classifies way too much material. That’s true, but it’s to be expected in the galactic capital of ass-covering, where long tenure is typically evidence of talent to escape accountability. Of course the federal government will avail its hirelings of every possible instrument to hide their screw-ups from those who pay their salaries—that is, the American public.

If Biden’s problem was just the U.S. classification system, the president’s team wouldn’t have hired top Democrat fixer Bob Bauer as Biden’s personal lawyer to pick up the pieces. The fact that Obama’s former general counsel is running the show is evidence that the scandal has the White House and senior party officials worried.

Before Bob Bauer came on, Biden was represented by Covington & Burling, home to Obama’s first attorney general, Eric Holder. Biden’s Covington cleaners included James Garland, Holder’s deputy chief of staff at DOJ, and Robert Lenhard, a member of Obama’s transition team who later represented the super PAC supporting Obama’s reelection.

Also part of the Covington team was Dana Remus. She served in the Obama White House, and was later general counsel for the Obama Foundation. She also represented Michelle Obama, and Barack Obama officiated her 2018 wedding. Remus had been Biden’s White House counsel until July, and she joined Covington in October. Within a month she was representing Biden in the matter of the classified documents. Remus did not respond to Tablet’s questions concerning when she first became aware of the documents in Biden’s possession—whether it was while still at the White House, after she left the administration but before she started at Covington, or on or around the official Nov. 2 start date of the crisis.

Bauer’s wife, Anita Dunn, once the Obama White House’s communications director, was reportedly among a small circle of advisers who counseled the White House to keep news of the scandal under wraps. When the Biden team was ready to go public, it leaked the Penn Biden Center story not to Washington journalists but rather to reporters based in Chicago, the epicenter of Obamaworld. Presumably it was leaked out of the Office of the U.S. Attorney in Chicago, John Lausch, named by Garland in November to conduct a preliminary investigation into the Biden matter.

Lausch is one of two Trump-appointed U.S. attorneys who kept their jobs when Biden came to office. His extension was supported by Illinois’ two Democratic senators, Dick Durbin and Tammy Duckworth. By tapping a Trump appointee to look into Biden’s problems, Garland gave the impression that the investigation was on the level. But the investigation is performative, just like the DOJ investigation of the president’s son Hunter, which is led by U.S. Attorney in Delaware David Weiss, the other Trump appointee who kept his job.

The next story about Biden’s issues with classified documents, this time found in the garage of his Delaware home, also looks like the result of a friendly leak. It was given to NBC journalists Carol E. Lee, a reporter said to be close to Obama’s former deputy Ben Rhodes, and Ken Dilanian, whose reputation for working in coordination with U.S. spy services has earned him the title of “the CIA’s mop-up man.”

In this context, it’s worth remembering why the Democrats called on Beltway allies to defend Hillary Clinton after the FBI opened an investigation into her private email server in 2015. The problem, it seems, wasn’t that she exposed American secrets, but rather that if her emails leaked before the election they might reveal the nature of her business arrangements with foreign governments, and thereby help Trump to the White House.

So her campaign devised a plan. In the event her emails were leaked, they preemptively blamed Vladimir Putin who, according to the Clinton scheme, published them to help her Republican opponent. And that’s how the long-running ruling class conspiracy known as Russiagate was conceived. As with Clinton, the concern over Biden’s case seems to be less about mishandling classified documents than the possibility that the documents might go public and give evidence of wide-scale corruption.

Classified records found in Biden’s possession are reportedly related to Ukraine, Iran, and the United Kingdom. The Justice Department has also seized handwritten notes that Biden took as vice president. Some of the documents in Biden’s possession reportedly date back to his time in the Senate, including his time as head of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee. It sounds bad that he’s been doing it so long, but insofar as it comports with Biden’s reputation for gaffes, it’s ameliorative—the president isn’t criminally culpable, just a little absent-minded, always has been.

But if Biden had shown an inclination to remove secret documents from classified settings, aides and intelligence officials would have long ago devised some means to protect him, the documents, and most importantly themselves. A scenario in which a senior official pocketed U.S. records over the course of several decades without ever being checked by the scores of minders attending him is improbable.

So is the official account explaining how Biden wound up leaving the White House with classified documents. If, as reported, all his belongings were packed in a frenzied rush as Biden departed the vice president’s office in January 2017, a deputy detailed to know what boxes with what content were destined for his home, his office, or his beach house would have also seen that some contained papers with classified markings. And it’s hard to believe that Biden’s legal team found the records sorting through his papers at the Penn Biden Center. Packing boxes is the work of administrative staff and interns, not the former White House counsel and other high-priced D.C. lawyers.

The inconsistencies, and outright fabrications, in the administration’s account, are largely resolved in the Berger scenario.

The book Biden was researching after he left the vice president’s office is Promise Me, Dad, his November 2017 memoir about two years in the vice presidency, 2013-15, during which he was also dealing with his son Beau’s fatal illness. In the book Biden also discusses his conversations and meetings with prominent world leaders, details of which were recorded in papers kept at the National Archives. Did Biden’s problems with classified documents, like Trump’s, begin in the same place?

It would explain why the records have been discovered at various sites: He simply laid them down wherever he landed—home, office, beach house—upon returning from the archives. It also explains why his lawyers and the DOJ are continuing to look for documents after nearly three months—because the archives has a record of what was printed out for Biden to review. It has taken so long to locate the records because the president cannot remember where he put them. It also explains why the archives has been so quiet about the scandal: They’re in the middle of it.

In the Berger scenario, the cover-up would have gone like this: Well before the Nov. 2 date given in the administration’s account, with momentum building for Garland to indict Trump sometime before the election to cripple Trump-endorsed candidates, an anti-Trump activist at the archives would have passed on word that Biden advisers should know the president had his own issues with mishandling classified information. Best to get ahead of it because we all know Trump’s MO: If you throw a grenade in his trench, he’s going to toss it back into yours.

And the Berger scenario answers the biggest question of all: Why didn’t the Biden team just make the story go away? After all, the national security apparatus, media and social media buried Hunter Biden’s laptop by labeling it “Russian disinformation.” But this was different—the archives has an indelible and permanent record. Biden advisers knew that at some point, once they’d put everything in place, they’d have to release the story.

The National Archives also had a record of most of what Berger had taken, but that’s not why he was caught. A congressional report on the Berger affair shows that archives officials failed to observe procedure and Berger took advantage of his rank. Rather than compel him to review the classified documents in a specially compartmented information facility, or SCIF, officials at the archives let him use their offices, where he reviewed Clinton records. He’d say he needed to make an important phone call and thereby, according to the congressional report, “procured the absence of Archives staff so that he could conceal and remove classified documents.” He walked out with documents as well as notes he took of the classified documents he reviewed. Berger must have been worried he was being watched because he left some of the stolen records at a nearby construction site where he could retrieve them later. He may have removed original documents for which there were no duplicates.

Unlike many records classified by the U.S. government, the ones Berger stole really did touch on matters of national security. They were part of the history of how a foreign terrorist organization slaughtered nearly 3,000 people under the noses of national security officials tasked with protecting Americans.

The National Archives’ inspector general wanted to alert the 9/11 commission that Berger might have taken original documents. There was no way to know since there were no copies. The official believed that the 9/11 commission should know that some of the record might be lost forever, a possibility that should shape the commission’s assessment of Berger’s testimony at least, if not the Clinton White House’s 9/11 record as a whole.

The DOJ never passed those warnings on to the 9/11 commission because the Justice Department was watching out for the Clintons, as it has for the last quarter century. One of the senior DOJ officials involved in the Berger investigation was current FBI Director Christopher Wray. One of the FBI agents investigating Berger was Charles McGonigal. He was also part of the bureau’s unlawful Trump-Russia investigation. Last month he was indicted for taking money from a sanctioned Russian oligarch.

The period Biden was reviewing in the archives, 2013-15, was also when Hunter Biden embarked on the most ambitious leg of his campaign to capitalize on his father’s vice presidency. Do the documents Biden took shed light on his role in Hunter’s foreign business deals? In December 2013, the vice president gave Hunter a ride to Beijing where he struck deals worth millions of dollars with Chinese officials. Most famously, a month after his father’s April 2014 visit to post-coup Kyiv, Hunter was appointed to the board of a Ukrainian energy company, Burisma, that paid him $80,000 a month. In early 2015, the vice president threatened to withhold a billion-dollar loan guarantee from the Ukrainian government unless it fired the prosecutor investigating Burisma.

Hunter may have been motivated to get as much as possible as quickly as he could because, as far as the Bidens knew, their time in the White House was winding down. The vice president was not favored to succeed Obama; Obama didn’t want him to. But against the odds, Joe Biden fulfilled his dying son Beau’s wish and returned as president to 1600 Pennsylvania Ave., where he finds himself in the middle of a scandal that would have never materialized were he not determined to destroy his predecessor.

Even if the Biden team’s account is correct, Biden’s records from the time of his son’s global gold rush should have been delivered to the National Archives after the vice president left office. And if they were, they would have been kept under the supervision of bureaucrats connected to a billionaire Biden fixer.

Lee Smith is the author of The Permanent Coup: How Enemies Foreign and Domestic Targeted the American President (2020).