Congregation B’nai Kabul

Most of the time, Larry Bazer runs a shul in Massachusetts. But for the past six months, he served in the military as the only rabbi in Afghanistan.

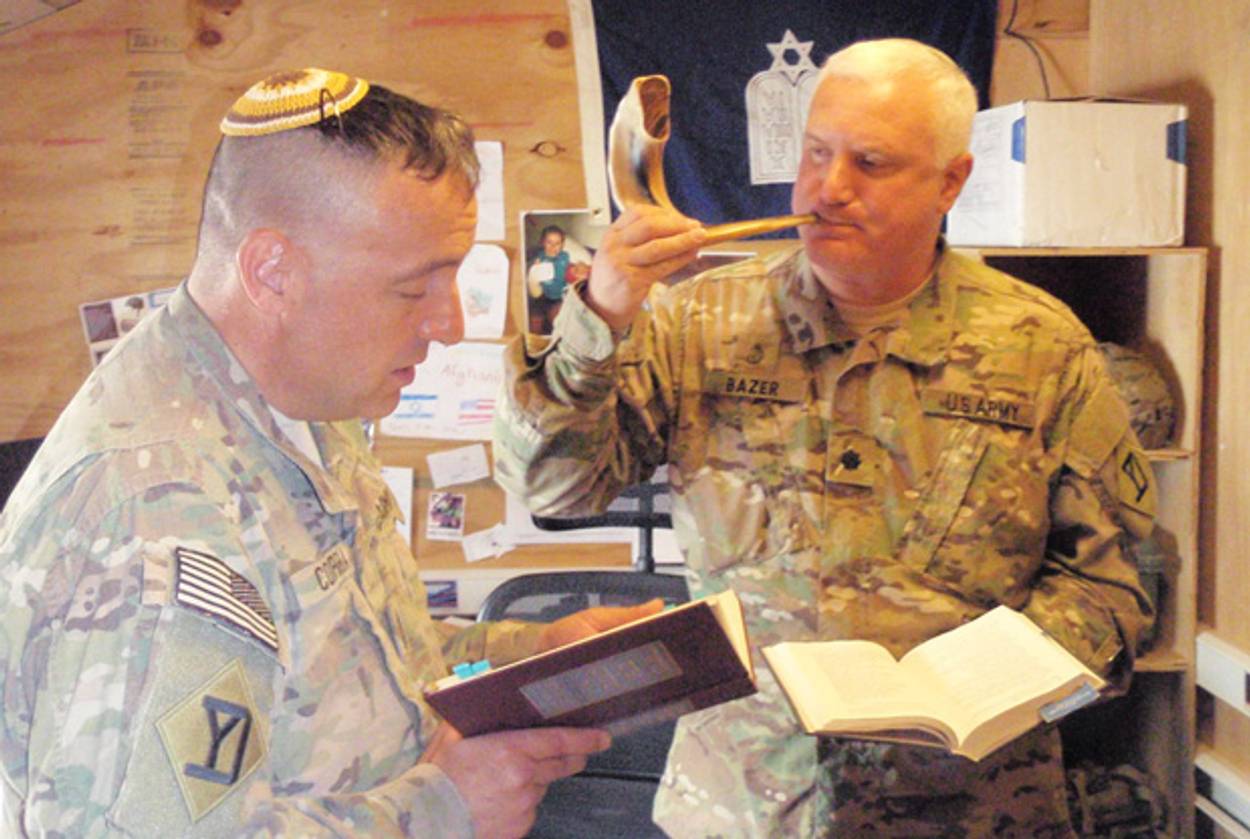

At 4:00 in the morning on Aug. 5, 2011, Lt. Col. Larry Bazer, a 48-year-old from Massachusetts, stepped off the C-17 at Bagram Air Base, roughly 40 miles north of Kabul, Afghanistan. Unlike the hundreds of soldiers coming and going that day, Bazer didn’t carry a weapon. Instead he dragged a 100-lb. trunk that contained a Torah, a shofar, prayer books, and other religious items he would need during his deployment—the first in his 22-year military career—as a military chaplain and the sole rabbi to the Jewish soldiers in the country.

After a short flight aboard an old Russian helicopter run by a contracting agency, he arrived at his final destination: Camp Phoenix, a military base on the outskirts of Kabul, where his unit, the Massachusetts Army National Guard’s 26th “Yankee” Brigade, had already been deployed. It was a Friday, so after a briefing with the base’s commanding officer, Bazer headed to the chapel to lead his first Shabbat service.

The chapel, said Bazer, “was a cozy little place”: a small, nondescript room built of plywood. During the day it was devoid of any religious symbols, but during the evenings a few crosses would turn it into a Protestant chapel, or some icons into a Catholic church. On Friday nights, candles and challah—sent each month by the “challah lady,” a Long Island Jewish woman—made it a synagogue.

Only four people showed up to Bazer’s first Shabbat service. One of the four was a Jewish first sergeant, who would later act as Bazer’s chaplain assistant when he traveled off the base; another was a contractor the rabbi had met during pre-deployment training. Together, those two formed the “nucleus of Jewish life” on base.

Camp Phoenix was a far cry from Temple Beth Sholom, the Conservative Jewish congregation of 265 families in Framingham, Mass., which Bazer leads in his civilian life. “Most of the time I live a life of a Conservative rabbi, teaching Conservative Judaism and practicing it and inspiring my congregants to do the same,” he said in a recent interview. “Here I was a rabbi to everyone, from traditional folks to Conservatives to Reform, Reconstructionists, non-believers, people interested in Judaism—you name it, that was my community.”

***

Bazer joined the U.S. Army in 1989 as a chaplain through a special program during his first year of rabbinical school at the Jewish Theological Seminary. In addition to a lifelong fascination with the military that began with G.I. Joes as a kid, Bazer wanted to join the military in order to follow in the footsteps of Rabbi Arnold Resnicoff, a Navy chaplain who served as a line officer in Vietnam and then as a chaplain in Beirut. “He was very big within our movement, and I wanted to be a Navy chaplain like him and be on aircraft carriers,” Bazer said. The Navy didn’t accept Bazer because he had had asthma as a child. Upon Resnicoff’s recommendation, he joined the Army in hopes of later transferring to the Navy. He never left.

But the decision to go to Afghanistan—like that of so many men and women—had its roots in 9/11. That morning, Bazer was at home in Long Island, writing a High Holy Day sermon as he waited for a man to arrive and install carpet. He watched the television as the first plane hit the North Tower at 8:46 a.m. “Then the second plane hit,” Bazer remembered, “and that’s when everything changed.”

Bazer didn’t wait for a phone call. He packed a bag, said goodbye to his wife and two children, and sped into the city, reaching 90 miles per hour after passing a checkpoint on the Long Island Expressway, which was empty except for emergency vehicles.

He parked at a fire station in lower Manhattan and started walking toward Ground Zero on foot. He looked up to find his usual landmarks that helped him navigate the downtown area, but all he saw was smoke. He was a chaplain for both the New York National Guard and the New York offices of the FBI, and his job was to be there for soldiers or FBI employees who needed to speak to someone outside the rigid command structure.

On the Saturday night following the attacks, Bazer was standing at the Pit, the rubble where the World Trade Center once stood. At 2 a.m., a firefighter captain walked up to him. They started talking, and Bazer asked if he had lost anyone from his firehouse. No one from his firehouse, the firefighter said, but he pointed to the Pit and said he knew at least 10 people who were in there. He asked Bazer to say a prayer for them. “At that moment, in the vast darkness of what happened to that place, it was in the presence of God,” he said. “That’s what we do as military chaplains—in challenging situations from 9/11 or being in Afghanistan.”

In Afghanistan, Bazer, who just returned home from six months in the country, says he wore “three yarmulkes.” The first was as chaplain of his National Guard unit. The second was as the Kabul Base Cluster Command Chaplain, which meant he oversaw several chaplains responsible for the religious activities of roughly 10,000 soldiers spread over eight bases in the Kabul region. Because he was the only rabbi in the country, his third was as the leader of the Jewish military community in Afghanistan.

As the country’s sole rabbi, Bazer went to different bases to perform Shabbat services. In early September, he traveled to a larger base in central Kabul, where the Jewish community had adopted the informal name of Congregation B’nai Kabul. The base was only 15 minutes away, but no trip “outside the wire” was simple. Bazer, who is about 6 feet tall and has white hair, would don his battle armor, Kevlar helmet, and protective glasses and mount one of the large armored fighting vehicles that would take him into the city.

The turnout for services at Congregation B’nai Kabul, which had a good lay leader, was the best Bazer experienced in the country: an average of between 12 and 18 people. Other bases were not so well-attended. At one base outside Mazir-a-Sharif, only one person showed up for Bazer’s Hanukkah service—and was 50 minutes late at that.

Suffice it to say, there aren’t a lot of Jewish soldiers in Afghanistan. What Bazer found, though, is that his presence often enticed people to come out of the woodwork and identify with their Jewishness. For Hanukkah, Bazer designed a 5-foot wooden menorah with energy-efficient lightbulbs that contract carpenters on the base—mostly local Afghans—built. It stood in the base’s central square during the holidays, right next to a Christmas tree. During the holiday, Bazer walked around wearing a large, blue menorah-like hat with a large Star of David and orange fabric flames. At one point, a French soldier asked to have his picture taken with Bazer in front of the menorah so he could send it to his Jewish mother.

One the highlights of his chaplaincy, Bazer said, was holding a bar mitzvah for a 23-year-old soldier who had missed out when he was 13. The ceremony was held on the first day of Hanukkah and was a coalescing event for the Jewish military community in Kabul. Between 35 and 40 people attended the ceremony—including the base’s non-Jewish commanding general. Half a dozen members of Congregation B’nai Kabul made the trip to Camp Phoenix in an armed convoy. The vast majority of attendants weren’t Jewish. “A lot of them thought, ‘Hey does he also need to get that little operation?’ You know, a circumcision,” Bazer recalled. “I said ‘No, he already did that’—so that was a running joke.”

When the lieutenant finished his Torah reading, Bazer gave the crowd an order that they could understand: “Fire for effect!” At that, everyone threw leftover Halloween candy at the new bar mitzvah.

***

Bazer insisted he never faced discrimination for being a Jew during his time in Afghanistan. Sure, his yarmulke caused some weird looks from local Afghans on the base, but he received some of the same stares in the mess hall when there were new people who didn’t know there was a rabbi on base.

He even found an Afghan tailor to make him a tallit in his uniform’s multi-cam pattern. It says Chaplain Bazer, OEF—for “Operation Enduring Freedom”—Task Force Yankee. “I think for him, the fact that I was Jewish didn’t matter. It was a job to do,” Bazer said. “I did try to have him make yarmulkes in the pattern, but he just couldn’t get that right.”

On Camp Phoenix, Bazer also got to know the Jordanian military liaison, and the two would often eat meals together. “Where else would an American Jewish officer and a Jordanian Muslim officer be able to sit down, have lunch, and talk about our families?”

Though Bazer’s particular unit arrived back in Massachusetts in February without any casualties, it didn’t mean it wasn’t dangerous. On Oct. 29, 2011, a suicide bomber rammed a car full of explosives into an armored bus from Camp Phoenix. Five coalition troops, eight coalition civilian employees, and Lucy, a chocolate lab who served as a stress-relief dog at the base, were killed. Bazer helped counsel soldiers affected by the attack and organized the memorial service that was held on base for the victims.

***

This week, Bazer rejoined his Massachusetts synagogue. He’s been home less than a month, but he’s already been in touch with his first sergeant, who is planning to attend services at Congregation Beth Sholom tomorrow.

Whit Richardson is a journalist who lives and works on the coast of Maine. He has written for National Geographic Traveler, Lapham’s Quarterly, and Down East magazine, and has produced stories for NPR’s All Things Considered.

Whit Richardson is a journalist who lives and works on the coast of Maine. He has written for National Geographic Traveler, Lapham’s Quarterly, and Down East magazine, and has produced stories for NPR’s All Things Considered.