Creative Trauma

Two thousand years of suffering and exile help an Israeli NGO teach Syrian and Iraqi refugees to build new lives in Europe

For more than three millennia, the Yazidi people had lived clustered around the sacred Sinjar Mountains in Northern Iraq. It was there, in the small hours of the morning of Aug. 3, 2014, that Maia’s life as she had known it ended.

She recalls how everything had always felt knitted together in the village where she grew up. Her father owned a café where her older brothers worked, and people would go to laugh and drink coffee and play dice games. Her favorite days were festival days such as one celebrating the sun, which the Yazidi worshipped as part of their unique nature-based faith deriving from the religions of ancient Mesopotamia. She, her parents, and five siblings would go from house to house, where they were welcomed with food and drink.

But on that night, they were awakened by gunfire as ISIS, which considers the Yazidis to be heretics, attacked her village. The onslaught would leave more than 5,000 dead while more than 10,000 women and children were taken as slaves. Maia and her family hid for several days and then fled by car, following a circuitous route toward the Sinjar Mountains, which are sacred to the Yazidis. Maia’s father, Hasso, thought a road was open, but as they started to drive an ISIS soldier blocked the road. Maia’s mother, Jemila, who has long honey-colored hair and an hourglass figure, smeared her face with ashes in hopes of making herself less attractive in case they were captured.

The soldier told them to put their hands over their heads. Retelling the story, Hasso holds up a picture he has drawn of his family and the soldier, poised to execute them. It was one of the two most terrifying moments of his life, he says.

The soldier called his commander. The commander’s response boomed over the radio: “What do you mean there are Yazidis? If they are not Muslims they should be dead.”

Just then, Kurdish forces began shooting at the soldiers and, in the confusion, Hasso drove off. When they reached the mountains, the family continued on foot, carrying Hasso’s mother in a sling.

High on the mountains, built upon what was said to be the final resting place of Noah’s ark, there is an ancient temple to which the Yazidis retreated during periodic genocides in their long history. But this time was different; ISIS was determined to finally obliterate them. Yazidis who tried to sneak back to their homes to get supplies were captured. The craggy peaks were mercilessly hot and dry in the August heat. The weak—the youngest and oldest of the 50,000 fleeing Yazidis who had gathered on the mountainsides—died of hunger and thirst. Some mothers even threw babies off the mountain to spare them suffering. Maia wondered if her family would die. At the memory, Maia’s face crumples into shadows and a silence falls.

Maia is startlingly thin, with a heart-stopping face: narrow, with huge brown eyes. She wears a dark brown T-shirt, too-short jeans, and a small necklace with a golden penny-size pendant, which she touches as she talks. I first met her in the summer of 2016, at a refugee camp in a town called Petra at the base of Mount Olympus. She had come up to me and offered a piece of watermelon, her face alight with pleasure at the gift. No one was around to translate. “Daesh … My uncle,” she said, using the refugees’ word for ISIS. She gestured, drawing her fingers across her throat, to indicate he had been killed. We tried to talk some more, but I couldn’t catch anything else. Her words felt like fireflies, disappearing into the dusk. I took a snapshot of her, and from time to time in the next year I found myself looking at her picture, wondering how she was doing.

When I returned to Greece, I tracked her down. The camp at Petra had closed, and she and her family were moved to an apartment in Katerini, on the northeast coast of Greece, which I visited along with Anat Seif, a short, energetic Jewish Israeli therapist in her mid-30s, who dresses in colorful bohemian clothing. Anat works for IsraAID, an Israeli aid organization whose work I have been following for several years in Greece, Germany, and America. While other NGOs focus on refugees’ material needs, IsraAID helps them cope with trauma and tries to foster resilience. Like Anat, most of the staff who work with Middle Eastern refugees are Arabic-speaking mental-health professionals who organize groups and activities in camps or visit the refugees in order to provide psycho-social support.

We sit on beds—some of the only furniture there—and drink sooty coffee and eat flat bread stuffed with meat that Jemila has made. The apartment itself seems bleak, a chilly expanse of cement and stone. The sense of desolation in the room is so heavy it feels as if we are sitting shiva.

Jemila recalls how, every morning in the mountains, she would make pitas with the little flour they had brought, and people would beg for them. “I didn’t know what to do because we didn’t have enough,” Jemila says. She would give each of her family members a pita and—even though they were all still hungry—she would give the rest away.

“You are very generous!” Anat exclaims encouragingly. Her intense desire to communicate seems to overcome the limitations of her Arabic. One of IsraAID’s therapeutic techniques, which they refer to as “narrative therapy,” is to get the refugees to tell their stories—on the grounds that “telling is healing,” explains professor Amia Lieblich, a prominent Israeli psychologist in the field of qualitative research and narrative studies who helped design IsraAID’s protocol. The staff does not just elicit traumatic stories: They find positive moments within those stories to highlight (the psychological term is spotlight): moments which showed strength, bravery, kindness, generosity, courage, or even just endurance. Because positive experiences do not have the same utility as negative ones in protecting us from harm, they tend to fade without spotlighting. It is as if there are a few silver threads in a tapestry of darkness, and the therapist looks for some threads to pull so that the tapestry—the fixed tableau of horror—begins to unravel and the memory of the trauma shifts. The goal is to help the refugees see that, although they certainly were victimized, they are not merely victims.

On the seventh day the family was in the mountains, anti-ISIS guerilla forces arrived in trucks to take the refugees to Kurdistan. Everyone prepared to leave, but a man came over and said his wife was giving birth and asked Jemila to help. Jemila looked around, but everyone else was running away, so, even though she didn’t know the couple and had never delivered a baby before, she decided she and her family would stay. It was desolate on the mountain; when the others left she could see how many corpses there were. She delivered the baby and severed the umbilical cord with a stone.

“That’s amazing that you did that!” Anat says, nodding her head, her brown curls bouncing. Jemila does not respond, and Anat continues, telling Jemila what a big heart she has, until she finally elicits the faintest of smiles.

“What choice did we have?” Jemila asks. Anat brushes away this objection. “It took a lot of courage,” she reiterates. Although her own family was in danger, Jemila chose to help bring new life into the world. Here was a new narrative about the terrible events: a story in which Jemila was a heroine, a story that could make her feel stronger.

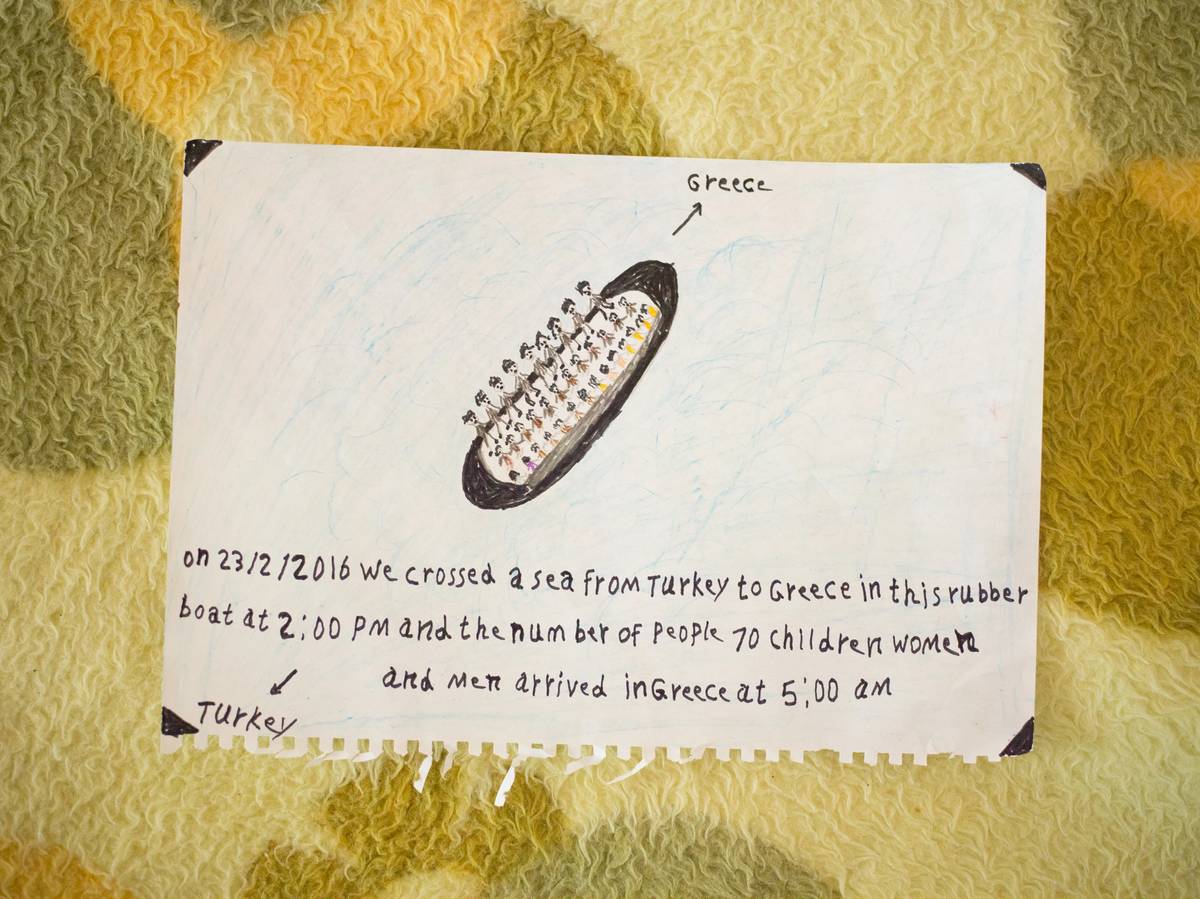

Hasso takes out another drawing he has carefully made for us showing the family on the flimsy rubber dinghy on which they traveled to Greece from Turkey in February of 2016. He says the hours they were on the water were the other most terrifying moments in his life. The family crossed at 2 a.m. in the darkness and cold. The smugglers crammed more than 50 people in a boat meant to hold a dozen and, as the journey progressed, the boat began to take on water and threatened to capsize. They were helpless; there was nothing they could do but wait to see if they would join the more than 4,000 refugees who had drowned crossing in 2015.

At dawn, their dinghy washed up safely on the shores of Lesbos, which refugees sometimes called the Island of Tears. They soon discovered they had accomplished the feat of escaping Iraq only to find themselves stranded in Northern Greece on the outskirts of Europe—on the wrong side of the barbed wire fence of Macedonia, where in 2015 more than a million refugees had flooded through. Instead of finding a new home, and a new beginning, they joined more than 60,000 refugees trapped in Greece who were waiting for asylum with no end in sight. There is no substance to their life in Greece: The adults can’t work; the kids can’t go to school—and indeed, had not been in school since the war began. They sit inside the apartment day after day, surrounded by Greek neighbors with whom they can’t communicate, or they walk an hour to the park.

Maia volunteers she would like to go to school again. She particularly liked math. When asked what she wants to be when she grows up, she answers directly in English, “Doctor. Helpful people.” With the defeat of ISIS, President Donald Trump and others have suggested such refugees should just go home. But Jemila and Hasso point out there is nothing to go back to in Iraq: Arabs now live in the Yazidi houses. Like the Jews, the Yazidis have been persecuted throughout the ages, enduring “74 genocides, all from Muslims,” Hasso says. The recent attack was not just ISIS: There were local Sunnis and Kurds who collaborated as well. Indeed, he says, the Kurdish army had advance warning of the attack and allowed it to happen—a belief that is held by many of the survivors.

“We want to live with Jews and Christians—people who are friends to us and have never tried to kill us!” Jemila exclaims. The Yazidis often look to the Jews as a model: They hope the recent genocide will strengthen their identity and that they will flourish in the West as Jews have done.

Maia and I step outside. Her eyes are still heavy with tears, but on the balcony, she grabs my hand and points to a peacock in the neighbor’s yard. (The Yazidis worship a peacock angel.) Her expression suddenly brims with excitement. She takes me down to the driveway and picks up an injured white pigeon that she has befriended. She holds him up to her face, his feathers against her cheek.

Since 2001, IsraAID has performed crisis-intervention work all over the world. Operating on a shoestring budget of $9 million a year, IsraAID has provided support for North Korean refugees in South Korea, tsunami victims in Japan, Ebola survivors in Sierra Leone, earthquake victims in Haiti, victims of sexual violence in South Sudan, and Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh, among others. They currently have ongoing programs in 19 countries, as well as providing immediate disaster relief, including to Houston, Florida, Puerto Rico following the hurricanes, and Santa Rosa, California, after the wildfires. In Puerto Rico, they sent about 50 doctors, therapists, and water engineers, and their team has remained there, with ongoing projects building water-filtration systems in remote areas and training local service providers to treat trauma and prevent post-traumatic stress disorder.

While IsraAID is a small organization, by international standards, with only 300 full-time staff, they have 1,500 volunteers in their database, consisting primarily of Israeli mental-health professionals, physicians, and people experienced in disaster relief. IsraAID staff includes both Arab and Jewish Israelis, as well as other nationalities. In recent years, the organization has had a particular focus on Middle Eastern refugees residing in Greece and Germany. While most of the refugees they work with are Muslim, IsraAID has a number of programs for Yazidi refugees, including providing support at a camp near Mosul for Yazidi women who were sexually abused by ISIS. In addition to northern Greece, a team remains on the island of Lesbos, where dozens of volunteers had met the 800,000 refugees who arrived in 2015.

The organization’s affable co-CEO, Yotam Polizer, says that the organization is “not political” and that their funding comes from foundations, private donors, the German government, and the United Nations. Indeed, he points out, being “a nongovernmental and nonpolitical identity allows the organization to work in places the Israeli government wouldn’t be able to.” But working with Middle Eastern refugees, most of whom are Muslim, is a complicated mission for an Israeli organization and inevitably raises political questions. Some Jews are skeptical of helping refugees, particularly Muslims, from Israel’s enemy states while some critics of Israel are opposed to Arabs or Muslims accepting help from Israelis.

The scale of the global refugee problem would appear to dwarf such concerns. There are more refugees now than at any time since World War II: Globally, there are more than 68 million refugees who have fled their countries or are internally displaced. The recent conflicts in Syria and Iraq alone exiled more than 6 million people. There are many ways to think about the refugee crisis, but one way is as a massive mental-health crisis: the creation of a vast traumatized population at risk for long-term dysfunction.

All of the refugees in Greece are suffering to varying degrees from the trauma they have undergone and have symptoms of anxiety and depression. Some unknown fraction will develop long-term PTSD or other conditions that will interfere with their ability to function. As Yotam points out, Israelis are experts in trauma. Overcoming the trauma of the Holocaust and the ongoing Arab-Israeli conflict is part of Israel’s national narrative. The premise of IsraAID’s work is that psychological work can be done—and, indeed, is all the more urgent—in the midst of crisis, when the situation is not resolved and the trauma of displacement is still present. But the goal of IsraAID is not just to treat distress and prevent long-term PTSD, but to facilitate what is called “post-traumatic growth.” Professor Lieblich, the Israeli psychologist, comments that, mysteriously, while some people develop PTSD, “for some people the process is the opposite. After the trauma, they gain something in their lives—in their identity—in spite of the losses.” And, she adds, there is evidence that psycho-social interventions aid post-traumatic growth.

It’s easy to misunderstand the theory of post-traumatic growth as an attempt to whitewash trauma. The goal is to help refugees see that while they truly have suffered irreversible losses, being a refugee also offers an opportunity. But, whereas the losses are forced upon them, they have to discover gains for themselves. Upon questioning, the refugees will acknowledge they know that, if they are accepted into a European country, their children will have better futures than they would have had intheir homelands even before the wars. The adults believe they will never feel at home in a foreign country, but express willingness to sacrifice themselves for their children.

The staff is always looking for ways the refugees can make their lives in Greece more similar to the ones they have lost. If the refugee worked as a barber, they provide him the tools to cut hair. If he worked as a taxi driver, they will talk to him to discover his other skills—if he plays soccer, for example, they will ask him to coach the children and organize games. On the island of Lesbos, where many of the refugee children have not been in school since the wars began in Syria and Iraq (and since the conflict in Syria is in its eighth year, many of the children have never been in school at all), IsraAID created The School of Peace, as they call it, where they honor Muslim as well as other religious traditions and hire refugees who had been teachers to instruct the children in their own languages.

“Everybody knows this is nowhere,” Ali, a young Syrian in a camp in Thessaloniki, tells me, mouthing the words of an old Neil Young song. Ali had been in Thessaloniki for more than a year, and, like many of the refugees, he knows much of his English from American music. Living nowhere makes the refugees feel they are no one. Their old identities can feel like the belongings they had to leave behind when they boarded the rubber dinghies to Greece. They feel they have come so far, yet their journey is still not done.

Before I spent time with refugees, I had not fully appreciated the agony of waiting. The refugees’ lives can be divided into three stages: first, the journey out of the Middle East to Greece; second, the time in camps waiting for asylum; finally, a new life in a new country. While the first phase is clearly the most difficult, paradoxically, the middle phase is the one where they become depressed. The struggle for survival triggers adaptive mechanisms: the heightened energy, focus, optimism, and drive that allowed our ancestors to strike out into unknown lands. But when they get to Greece and have to sit around for months or years, frustration turns to depression as the trauma catches up with them. As Primo Levi observed, almost no one committed suicide in the concentration camps; they were too busy trying to survive. The survivors—including, eventually, Levi himself—committed suicide afterwards.

With nothing to wake up for, families stay up until 3 or 4 a.m. and sleep until noon. Days dissolve in despondency and the kids run wild. Anat works primarily with refugees at three different camps clustered around Thessaloniki. “We try to make them see there is a present, not only a past and a wished-for future,” she says. It is difficult to persuade the refugees to invest in the present: to show up at groups or to get the children to attend classes—in short, to persuade the families that there is anything they can do except wait. People are reluctant to work in the camp garden because they don’t want to believe they will be there to reap the harvest. When I ask some parents if they would consider using the time to teach their own children, they respond, as one father put it: “What’s the point of teaching them to read and write Arabic?” In turn, the children lose faith that their parents can protect them, and stop listening to them.

IsraAID staff are forced to constantly remind the refugees that they have no influence in the inscrutable asylum process, a collaboration between the Greek government and other European nations. The interviews are supremely stressful. Refugees complain that the officials—trying to verify their identity—quiz them on details of the geography and history of their country that they have not learned since grade school. In their panic, they fear they gave the wrong answers. They are given no timeline for the process: After the first interview they have to wait an unknown number of months to be told when their second interview will take place.

Fares, a Yazidi Iraqi in his mid-20s, was captured by ISIS during the genocide and held for 30 days. He escaped by hiding in a chicken coop, and walked in the mountains for two days without food or water.

After he was free he chose to join Kurdish forces to fight Daesh, in order to “feel strong again.” The soldiers showed him how to tape a bullet to his shoulder so he would always have one for himself because “Daesh will kill you,” he says, “but they will kill you slowly. They will take one part of your body every day.”

Fares was asked his story at his first interview. Then, at a second interview six months later, he had to tell his story again and, at the end, the interviewer told him it was “90 percent” the same. “Of course, it’s the same—I lived it,” he told me desperately. Did 90 percent mean he passed, or would he be doomed by small discrepancies (traumatic memories tend to shift, but details could also be lost in translation). With his long romantic curls and finely shaped face and hands, he looks the part of the singer and classical guitarist he once hoped to be.

“Who knows what will happen now,” he says in a tone that indicates he still hopes it could happen, but accepts it may not. I imagine he will do well—he is just one of those people. Although he is without family, he has already created a network for himself and managed to get jobs assisting various NGOs (including translating for me). In every group, there are people like him who just seem buoyant.

But what about the other refugees: the ones who lack that extraordinary resilience? How can they be helped?

It’s tempting to say “I’m sorry” to refugees a hundred times a day. I am sorry my country has rejected you and you don’t know if you will wait for years only to be sent back to the charred remains of your country. I am sorry your cousins, friends, or neighbors drowned crossing to Greece. I am sorry your loved ones are missing; their absence on Facebook makes it clear they are dead or captive because modern technology makes it easy to get information, but has not changed the barbarism it documents. Fares tells me how he found out his friend died when a video was posted on Facebook showing him being shot by ISIS while carrying a young girl in his arms. Fares plays the video for me, pointing out that his friend was a Yazidi who gave his life rescuing a Muslim child from the fighting. Ahmad talks about leaving his elderly mother in Syria because she was too weak to make the journey and now she is alone and has nothing to eat. They videochat on WhatsApp and he can see her growing thinner and thinner. Choula, an Iraqi woman, tells me how she was forced to watch as ISIS beheaded her brother with a knife. They told her that if she cried, they would kill her too.

So many people urgently need help. A laborer from Mosul recalls how he stood with his wife and their children in the cold and rain in the back of a truck for more than 24 hours to escape Syria. Their 13-year-old twins, Matin and Moubin, are suffering from an unidentified neurodegenerative muscular disease that has already killed their eldest. The boys’ condition has worsened while they have been waiting for asylum—they have seizures and can no longer sit or hold their heads up. The couple stays awake at nights worrying the youngest one may have the disease as well; at 5, Joseph is just two years younger than the twins were when they began showing symptoms. The genetic testing that would diagnose him is not available in Greece. They are continually tormented by the belief that doctors in Western Europe could save their children. While they hoped their application would be given priority, it wasn’t. Everyone has a sad story. I’m sorry, I’m sorry, I’m sorry.

That is not, I learn, the most helpful response. Talya Feldman, a young American volunteer, recalls working with a Syrian woman who was struggling with depression. Talya kept stressing to her the impossible odds she had overcome in escaping the war as a single woman with three daughters, two of whom were severely disabled. Finally, the woman came to see her experience as a classic miracle story, with God having chosen her for her strength—and began rallying the other women to see their own stories that way, too. “The refugees who made it to Greece genuinely are amazingly lucky and amazingly strong,” Talya says. “You don’t have to reach to find those things—you just have to help them frame their story in a way so they see that, instead of seeing the suffering and the pain.”

If there are no silver threads for the aid workers to pull, they can be invented. Khalid Masri, a 27-year-old Palestinian-Israeli therapist with a handsome chiseled face and physique who runs several youth groups at the camps surrounding Thessaloniki, says he often uses exercises that employ imagination to help children transform terrible memories. He asks the kids to draw pictures of something bad, and when they are done, he asks them to take the same picture, but change it in a way to make it positive. Children frequently drew the terrifying boat trips most of them had made from Turkey to Greece. Khalid recalls how one boy redrew his wobbly dinghy as a grand ocean liner, as fancy as the Titanic. Another boy drew a picture of his school in Syria reduced to rubble. But when he redrew it, he rebuilt the walls and colored in grass and a sun and happy students.

Avital Furlager, an Israeli-American therapist who trained in dance therapy and helped design the Greek program, says there is evidence that trauma damages the part of the brain involved with language, and that creative arts can be used to access memories that are too difficult to articulate. In a women’s group at the Philoxenia camp in Thessaloniki, run by Anat Seif, who trained as an art therapist, the women were asked to draw a random scribble, and when they were done, to turn it into a picture. Mizken, a Kurdish refugee from Iraq, draws a rubber dinghy crossing the sea with dolphins on either side. She explains to me after the group is over that she has heard that dolphins sometimes help a boat cross safely. When I ask if dolphins had led their boat, she explains she had just added them to her drawing. Memories are fungible: When Mizken recalls the story, perhaps she will think of the dolphin and over time she might come to feel that there actually had been some kind of protective animal or spirit guiding them. After all, she survived.

When I was first introduced to IsraAID’s philosophy, I felt a certain aversion to it. I wondered if it was trying to put a lemons-to-lemonade gloss on refugees’ stories rather than understanding their true experiences. Journalists are trained to elicit their subjects’ stories while being as unobtrusive as possible. But in narrative therapy, the interviewer is supposed to shape what the subjects say by spotlighting positive moments, or helping them to reframe their stories into inspirational tales.

It was on my first trip to northern Greece that I understood the value of the technique. It was Aug. 3, 2016—the second anniversary of the genocide in the Yazidi homeland. I sat on a stone wall under the lacy canopy of a tree in the camp at Petra talking to an 11-year-old Yazidi girl named Nadal. Isa—a 22-year-old IsraAID staff member whom the kids all flocked to—translated. Isa himself is a model of hope for the refugees: He was the youngest of a Yazidi family of eight whose mother left Iraq many years earlier and raised her children as a single parent in Germany. All the children had grown into successful professionals (a dentist, a lawyer, a teacher, a psychologist, an architect), and were also engaged with helping other Yazidis.

As she talked, Nadal toyed with a bracelet of colored yarn on her wrist. Her cinnamon-colored hair was so long it touched the top of the wall. She and her family had fled the attack on their village, running over bodies into the barren mountains where they tried to flee to Kurdistan. Nadal talked about how they had to eat cactus, and the thorns had cut her tongue.

“I wish I had died along the way,” she said. She looked down and twisted her bracelet. “I haven’t had chips in three years.”

Isa touched her shoulder. “Want me to buy you some chips?”

She shook her head. Her cousins were in Germany now, she said. She talked to them on the phone sometimes; they could even speak German by now.

“I just feel life is unfair to us,” she said.

“That is certainly true,” I said, feeling the weight of the truth.

“I am not going to translate that!” Isa scolded. “You are supposed to be giving her hope!”

I felt a prickle of irritation: I wanted to explain that that was not my job. (Journalism 101: Mirror the subject’s feelings back to them.) But he was talking to Nadal and I could see her smiling faintly. Then he said something and her face lit up. “I told her you said she was brave,” he said, “and she has come so far she can’t give up now.” After that, I began to try to respond to refugees by telling them that I knew one day they could tell their children the story they were telling me and their children would know how amazing they are. Each time I said it, I could see how it worked: Their faces brightened.

The techniques had an effect on me personally as well. Temperamentally, I have always been a pessimist. I had always told myself I saw the truth of things—that I was not afraid to look at the darkness. But after spending time with IsraAID, I began to see it as a weakness. It’s just easier to be pessimistic.

The IsraAID staff found redemptive moments even in the most brutal stories. Mickey Noam-Alon, the communications director of IsraAID, told me about videotaping an interview with a Yazidi man. Mickey was trying to create a documentary archive of the survivors of the Yazidi genocide. He focused on two details in the man’s story. As they walked through the mountains, many of the adults were weeping, but they forced themselves to sing to comfort the children. And, at one point, the man had left the group and hiked five hours down the mountain to a stream he knew about and seven hours back up to bring water to everyone. Mickey told the man how remarkable it was that he got water and that he and the other adults had found the strength to sing in that situation. I knew from having watched IsraAID-videotaped interviews that the interview would be edited so as to emphasize those two details, just as an interview with a survivor of the tsunami in Japan highlighted a woman talking about the pleasure of sharing a cucumber with other survivors in the rubble—more delicious than any cucumber they had ever had. I knew that with that frame, the man had become a hero—the kind of person who saved his group from dying of thirst and sang through tears—and that would shape not only how his grandchildren saw him, but how he saw himself.

In every story, it turned out, it was possible to find something to highlight. IsraAID had arranged for me to talk to a young Yazidi woman in Hanover, Germany, a medieval town of Gothic churches and old stone houses winding around a river. We go upstairs to a small room on the top floor of the house where we meet. At first glance, Marwan looks like any pretty young woman, dressed in a light summer top and skirt and fancy sandals decorated with gold baubles. But, as she talks, her depression becomes evident. She slumps into the couch, her voice flat, her eyes dull. I worry that telling her story might be traumatic and wish an IsraAID staff member were with me. After she was captured during the Yazidi genocide, Marwan had been taken to Raqqa and sold to commander after commander who would resell her when they tired of her. Daesh appears in all of the refugees’ stories, in the background or foreground: black masks of faceless evil who, like zombies in a horror movie, can enact limitless evil on humans because they are no longer human. Yet, sometimes an atavistic moment of humanity inexplicably surfaces.

The last commander who owned her “was very bad to me,” she says, and raped her often. The commander was married, and in the months that she lived there, his wife did not speak a word to her. Her uncle got in touch with the commander and offered to buy her back, but he did not wish to sell her. One day, Marwan smashed a glass bottle and began cutting her wrists with it. The commander ordered her to stop. She kept on cutting, telling him she would only stop if he let her go and—inexplicably—he said yes. “Swear it on the Koran,” she said, pushing his hands on the nearby book. He swore.

That was it, I realize: the moment an IsraAID therapist would highlight. You were not afraid to die to gain your freedom. You are that strong.

“Not so much,” she murmurs, but life floods into her face.

IsraAID’s belief is that by transforming the way the refugees see themselves from victim to survivor and weak to strong, the refugees will not only feel better, they will also present themselves better and will therefore be more likely to inspire others to help them. Improving the image of refugees—rebranding them, so to speak—is critical to their success. Under Trump, America has all but closed the door on Middle Eastern refugees. In 2018, out of the more than 6 million Syrian and Iraqi refugees, the United States has found room for all of 60 Syrians and 130 Iraqis (as of Aug. 31). The critical factor behind these policies is the question of what image of the refugees prevails. Even if they aren’t actual terrorists, are refugees weak, sad, broken people who will be a drain on society? Or are they heroes, people who fought to live another day a thousand times over? Everyone wants to back a winner.

One might assume that refugees’ tales speak for themselves: that stories of loss, suffering, cruelty, and injustice naturally motivate others to help them. In fact, the opposite can be true. Pity is a vexing emotion; there is a good deal of evidence that people dislike feeling it and avoid or reject people who conjure it. Altruism originally developed within tribes; confronted by weak members of other groups, people feel the need to conserve resources and withdraw. Foreigners who evoke pathos are at risk of being seen as pathetic, and the suffering of others can be seen as self-inflicted, exaggerated, maudlin, or simply nonexistent, as in Trump’s descriptions of asylum seekers’ “phony stories of sadness and grief.”

IsraAID staff often analogize the plight of Middle Eastern refugees of today and that of Jews during the Holocaust. Since the tragedy of the Holocaust is now universally recognized in the West, it’s easy to forget that at the time Jews had no more status than Middle Eastern refugees do now. America did not offer visas to Jewish refugees trapped in Nazi Europe; stories about the death camps were widely ignored. Just as the public is concerned now that some of the refugees might be members of ISIS, Jews were denied visas on the grounds that they might be Nazi spies, or communists. Even children were seen as undesirable. When it was proposed that America at least accept Jewish children, as England was doing with the kindertransport, the idea was rejected. “Twenty thousand charming children would all too soon grow into 20,000 ugly adults,” famously declared the prominent wife of the U.S. immigration commissioner.

How can today’s refugees present themselves in a way that makes it more likely that other groups will identify with them? After all, refugees are indisputably courageous and resourceful: They are the people who made it out of war-torn countries. The life of a refugee could be seen as a classic hero’s journey if it is framed that way, with its narrative of overcoming impossible obstacles, undergoing transformation, and searching for a home. (As I write, I can hear the sounds of my 8-year-old daughter and her friend playing “poor homeless orphan girls having a tea party.” Naturally, they are not picturing themselves as piteous, but as plucky, brave, and adventurous.)

In the decade that followed the Holocaust, prominent American Jews and others worked to sell the story of the Jews to the public through uplifting stories—books, movies, and plays—such as that of Anne Frank, who became a symbol of eternal optimism. These stories deliberately minimized the Jewishness of the characters; their pitch to American audiences was the Jews are just like you. IsraAID tries to advance the converse idea: The Middle Eastern refugees are the Jews of today. Here is our chance, as Americans, to right a historical wrong. Maia and Nadal need not become the Anne Franks of today: They have a chance at a happy ending.

IsraAID opened its first U.S. office, in Palo Alto, California, a few years ago, and I have attended a number of the group’s events and benefits where Yotam Polizer, the co-CEO, speaks. Yotam has a soft-spoken style, conveying an air of modesty and goodness. At an evening event, Michelle Sandberg and Sabrina Braham, two local pediatricians, talk about doing a medical training at the desolate Kakuma refugee camp of more than 150,000 in northwest Kenya. Yotam then tells anecdotes about dangerous situations he has faced, emphasizing his fear, rather than his bravery, and various comical missteps (such as climbing into rubble to rescue a woman trapped in the Nepalese earthquake for six days and accidentally using formal Nepalese diction shouting to her). Looking around the room, the response is overwhelmingly supportive.

No one disputes the value of IsraAID’s work in providing disaster relief from hurricanes and earthquakes, but the response to events about IsraAID’s work with refugees in Greece is considerably more complicated. Some people bristle at the analogy between the Middle Eastern refugees and the Jews. A number of people privately express apprehension about aiding refugees from countries that have vowed to destroy Israel.

“Some people say Jews should just help themselves,” Yotam comments, “but if you read the Torah, the number one mitzvah is helping a stranger because we were strangers in the land of Egypt, which I interpret to mean not just helping other Jews, but helping vulnerable non-Jews as well—and even helping people who are considered to be our enemy,” he says. “I would say this is actually the mostJewish thing to do.” That ethos seems to have support in Israel: Israelis are on the forefront of disaster relief everywhere.

Yotam recalls a speech at a large synagogue in New York in which one member of the congregation responded that, in rescuing a Muslim baby, “You are helping future terrorists.” But, he points out, “by building bridges and helping the refugees to integrate in Germany, we are actually reducing the chances of them joining extremist groups.”

Refugees often remark that IsraAID workers are the first Jews they have ever met; the encounters make them realize—as one man told me—that everything they were taught about Jews back home was a lie. And the refugees are at a unique juncture in their lives where they are questioning the nationalistic propaganda they had been schooled in. When the refugees arrived at Lesbos they were greeted by IsraAID staff, offering candy, blankets and medical treatment. An IsraAID doctor set broken limbs (limbs were crushed as passengers in the crowded boats were slammed into each other by waves), revived people pulled from the water, and even delivered babies on the beach. Yotam once rescued a 4-year-old girl from the water and brought her to the medical team. Her father (who turned out to be an engineer from Damascus who spoke fluent English) told Yotam, with astonishment, “My worst enemy has become my biggest supporter, and the people who are supposed to protect me at home—the government—are chasing me away.”

“We break the way Arabs think about Jews,” comments Guy Shayer, the head of mission in Northern Greece. But the encounters also change the IsraAID staff, who include both Jewish and Arab Israelis. Guy—a 30-year-old Jewish Israeli—shares an apartment in Thessaloniki with Khalid Mastri,who, although an Israeli citizen, identifies himself as a Palestinian. Both he and Natheem Ganayem, an Arab social worker from the north of Israel whom I met in Germany, said that they initially hesitated to work for IsraAID, but they believed they could connect with the Arab refugees better than the Jewish staff. Over time, they came to trust the motivations of their Jewish co-workers.

“Being a refugee is an important part of the identities of both the Israelis and the Palestinians,” Yotam remarks. “For them to come together to work with other refugees is a very powerful and innovative approach to the Israel-Palestinian conflict. They are working together, saving lives together in a way that’s very in touch with the identify and history on both sides.”

Guy—a and former soldier with soft brown eyes and a three-day stubble—told me that in Israel, he did not have any Arab friends. He takes satisfaction that here, united by a common purpose, he and Khalid are not only colleagues and roommates, but friends. “I had never met Syrians before I came here,” Guy says. In Israel, “they are right there, in our backyard, but you never cross that barbed wire. You have all this stuff in your mind …” He gestures, as if to brush aside the stereotypes, “and then you meet them and it’s nothing.” When Guy describes his work for IsraAID to people back home in Israel, he says they sometimes respond, “But you’re helping Syrians … But they’re Syrian … Syrian!” He laughs, a laugh that contains both ridicule for prejudice and pleasure at being free of it. I glance at Khalid, but his face is impassive.

While staff stress that IsraAID is not a political organization, they do occasionally encounter hostility toward the organization as an Israeli one—not from the refugees themselves, but from other NGOs. IsraAID needs the goodwill of other NGOs to grant permission to enter the camps those NGOs manage—and not all of them allow it. Joel Hernandez, an American from Texas, works for a Canadian NGO managing a camp called Elpida built in a former recycling factory on the outskirts of Thessaloniki, where IsraAID provides support. He says that he personally welcomes IsraAID, but he points out that not everyone agrees.

He has heard it argued, he says, that, for Syrian and Iraqis, Israelis are the oppressor, and therefore to force them to accept help from Israelis is humiliating—a betrayal of their own culture that might be traumatic. After all, he points out, the refugees are in no position to refuse help. IsraAID staff, their bright red T-shirts displaying the name of the organization, are often the first ones to greet new arrivals on the beach. “Arguably, changing the refugees’ relationship to Jews could be considered part of acculturating to Europe,” Joel says, “so it might be more appropriate for IsraAID to be involved when they have asylum in Germany or other countries and are less vulnerable and have more choice.”

“That’s an old argument—we just focus on the work,” Yotam responds. “When you look at the facts it’s hard to accuse us of propagandizing. In Lesbos we were one of the first on the ground and one of the few left now—we call it FILO: first in/last out—because the healing process takes time. If those NGOs care about refugees so much, they’d still be there.”

The organization’s philosophy is to support the refugees’ own identity, while also helping them prepare for a future in the West—a complicated balance. Khalid Mastri constantly reinforces to his youth groups that if he, a Palestinian growing up in Israel, has been able to maintain his Arab identity, then they too can hold on to their Arab identity in Germany or whatever European country ultimately accepts them, so that “they don’t lose themselves when they get to the West.” But Khalid also wants to help the kids he works with westernize in ways he believes will be adaptive. In the youth group he runs for boys at the Elpida camp, he makes the boys stand up and share their feelings with the whole group—not an Arab practice.

“What is your dream?” Khalid asked his youth group one afternoon, his voice filling the classroom. It is a warm afternoon, right after lunch, but at the sound of his voice the boys wake up.

“Stand up and tell me your dream!” he commands—a dream, that is, beyond the one pressing hope all the boys share of getting out of the camp. One by one, the boys—tweens and teenagers from Syria—reluctantly rise to their feet. There is an aspiring engineer and a movie star, while the rest dream of being soccer stars in Germany.

With a dramatic gesture, Khalid draws a red line on the white board with a circle on the end. “This is your dream!” he thunders, pointing to the circle. “This is your journey. Where are you now on this line?”

The boys look cowed.

“It’s up to you what you accomplish! It’s up to you if you reach your dreams.” His tone conveys: You can do it and, if you don’t do it, it’s going to be your own fault, in what at first strikes me as a tone better suited to a motivational speaker than an aid worker addressing hapless refugee children. But I come to see how passionately he wants them to succeed. “Focus on your dreams, believe in your dreams, nothing can stop you,” he exhorts them. “You are not just refugees, that your life will end here. Believe in this and it will happen!” He commands the boys to come up to the board and mark their progress.

One by one, the boys stand before the red line on the white board that Khalid has drawn to represent their journey. They choose places in the middle to mark their lives: They know they have a long way to go, Khalid tells me later, but he has also succeeded in making them realize that they have come a long way—such a long way, he reiterates to them, that there is no way you can turn back now.

“In my youth groups, there are two children who saw their mothers die in front of them during bombing attacks in Syria,” Khalid tells me. When he used to try to ask them about it, they would shut down and he would “see the fear in their faces.” But now they are beginning to open up, he says, and can talk about it with the whole group. “I see that the death is more behind them,” he tells me. “It will not go away. We are not doctors that we will remove the illness—there is no pill we can give them. But they are continuing with their lives, looking further for their dreams.”

The boys seem impressed by a documentary Khalid shows them about successful Syrians in England. An engineer who has recently received an award talks in Arabic about his work, accompanied by swelling inspirational music and a montage of his successful life.

“He is so successful that England picked him to represent England!” Khalid tells the boys. But the man is also saying that he is proud to be a Syrian on the world stage, Khalid points out. “You can represent your new country and still be Syrian,” he says, adeptly picking his way through a minefield of familiar identity issues. Then he returns to his mantra. “Focus on your dreams, believe in your dreams, nothing can stop you. Believe in this and it will happen!”

While the staff would never wish to encourage Muslims to “delete their own culture and roots,” Yotam says, he points out that there are practices in a patriarchal society that will not work in the West. The IsraAID’s Arab staff are in a particularly good position, he says, to try to help the refugee women to be more empowered, as well as generally fostering “more acceptance and openness for other cultures including the Jewish one.” That, in turn, will make the refugees more likely to be accepted.

On my first trip to Germany to see IsraAID’s work there, in 2016, Samuel Schidem, a Druze Israeli, took me on a tour of the Holocaust memorial in Berlin that he had also given to Middle Eastern refugees who had learned in school that the Holocaust was a lie. The construction of the museum is designed to induce feelings of foreboding and anxiety in the visitor that evoke the experience of the victims—and, for the refugees, echo their own experience. As he led me through the catacomb of dark corridors, lined with documents of the dead, he told me how he could see in the new refugees’ faces the reality of the Holocaust dawning. And with that realization, he said, the refugees had taken another step toward joining the West.

But do they want to join the West? Arab men are often deeply conflicted. A few days spent observing Natheem Ganayem’s work with men in Frankfurt makes clear that the loss of status the men feel in Greece will only deepen in Germany. Unlike women who still have their roles as wives and mothers, the men have lost their professions and the pride of being able to provide for their families that is central to their identity. They are not permitted to work until they learn German.

Natheem, who wrote his master’s thesis on masculinity in Syrian immigrants, tells the men that if their wives and children are disobedient, they cannot beat them; if they do, the government will take their children away. They have to accept being bossed around by the German women who run the shelters and social service agencies. If a German woman walks down the street in a miniskirt, she is not a prostitute; if she says “hi,” she does not mean she wants to have sex.

In a men’s group that Natheem runs in a shelter, the men sometimes tell him that they want to give up and go back to Syria or Iraq, he says. Or, feeling there is no place for them anywhere, they talk about suicide. Breaking a Muslim taboo, Natheem asks the group to actually role-play the scenario. He himself plays the part of a suicidal man.

“What will happen to me if I kill myself?” he asks the group.

“You will go to hell,” the men swiftly reply.

“What will happen to my family, to my children?”

No one can bring himself to answer.

The day I visit the men’s group, it is dominated by Zohir, a Sunni Muslim from Syria who is illiterate and struggling to learn German. Natheem takes his calls day and night, trying to keep him from having a breakdown. A stream of Arabic bursts forth from Zohir as he talks about having been alone with his 6-year-old daughter, Masah, for a year and eight months. Zohir is forced to be both parents to his daughter: to cook for her and choose her clothes and struggle to do her hair—all of which she complains about. He also has to help her bathe and use the toilet when he is uncomfortable seeing her naked. “I am a man,” he exclaims, his voice edged with despair.

He feels that his family is falling apart. His wife does not understand he is powerless in the legal process to unify the family; they fight on the phone at night. Masah doesn’t want to come to the phone to talk to her mother anymore. He recently went to court, accompanied by Natheem, only to discover his papers had been lost.

But when Natheem and I visit their home—a single, shared room—his bond with his daughter is evident. Masah, clad in a short peppermint-pink dress, is just home from kindergarten. She chatters excitedly about her day; she loves school and is already fluent in German. She shows me her notebook with a picture of a princess that she has carefully sketched. Then she settles herself on her father’s lap; he rests his hands lightly on her shoulders.

“I want to be a princess when I grow up,” she tells me solemnly. “But first we need asylum status.”

I try to envision a future for her and find my thoughts drifting back to Maia and Nadal. They were all in the middle of their journeys: marks on a line that disappears into the future. They had encountered evil and hardship—sorrow, thirst, and thorns—and they showed strength and courage and perseverance. They would find a new home; they had come too far to turn back. Focus on your dreams, believe in your dreams, nothing can stop you. Believe in this and it will happen.

This article was first published by Tablet magazine on the Atavist platform.

Melanie Thernstrom, a contributing writer for The New York Times Magazine, is the author of The Dead Girl, Halfway Heaven: Diary of a Harvard Murder, and The Pain Chronicles: Cures, Myths, Mysteries, Prayers, Diaries, Brain Scans, Healing, and the Science of Suffering.