Daniel Libeskind’s Holocaust Memorial Message

The architect addressed students at FIT’s Yom HaShoah commemoration

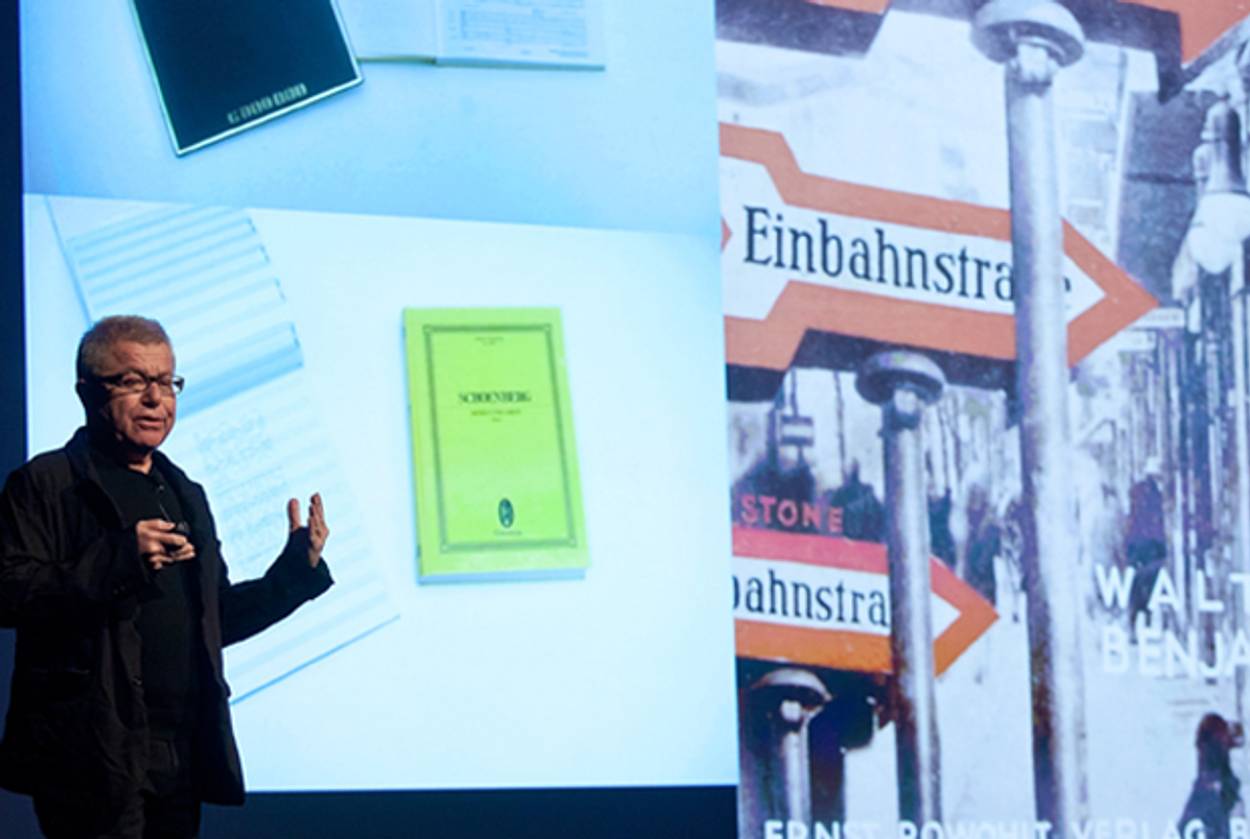

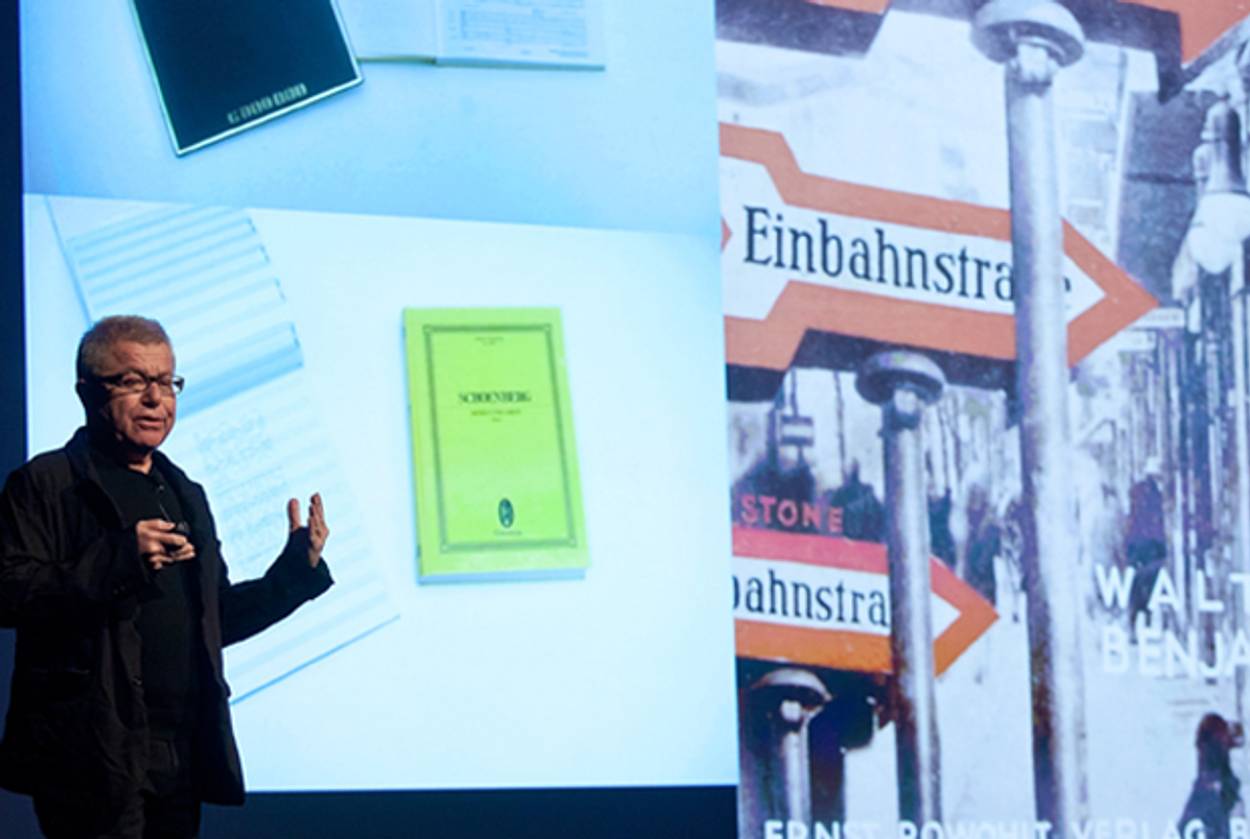

“A building is a place where voices whisper,” Daniel Libeskind, the architect who designed the Jewish Museum in Berlin, told a rapt audience at the Fashion Institute of Technology’s 13th annual Holocaust Remembrance Day event yesterday. “When you listen closely, structures speak—they even sing.”

Libeskind, who has brought his signature jarring curves, unexpected lines, and bold shapes to the Danish Jewish Museum, the Felix Nussbaum Museum, and the Military History Museum in Dresden, is the son of Holocaust survivors, and his work heavily mines themes of memory and remembrance. His lecture brought together an eclectic crowd—FIT students with drawing pads and pencils sitting in during their lunch breaks, several Holocaust survivors, and a group of religious Jews.

After the war, Libeskind told the crowd, his parents returned to his father’s Polish hometown of Lodz to find that nearly every relative had been killed. Daniel was born there in 1946, before moving to New York with his family during his teenage years.

“I arrived by ship to New York as a teenager, an immigrant, and like millions of others before me, my first sight was the Statue of Liberty and the amazing skyline of Manhattan. I have never forgotten that sight or what it stands for,” Libeskind said. That memory inspired his design for the new World Trade Center, which celebrates “freedom, renewal, and life.” He added that the memorial, which leaves some of the site’s original foundation visible to the public, pays tribute to the resilience of the New York spirit. “That’s New York—we’re the type of people who keep rising, no mater what pushes us down.” he explained. “I thought about my parents while I designed the new World Trade Center. They were immigrants from Poland, who came to America, with so many others, hoping to breathe free. I don’t take that dream for granted.”

In a strange twist, the Jewish Museum Berlin opened for the first time on September 11, 2001. “The museum was open for a few hours—then, when they heard about the attacks, the doors were immediately closed,” Libeskind recalled. “Nothing in history is disconnected.”

After the success of the Jewish Museum, Libeskind’s designs were soon in demand. His buildings are supposed to be experiential, and his goal is to recreate history through his work. “A building is a text that is interpreted not only by the conscious, but by the subconscious,” he said. “I want visitors to walk through the halls and down the staircases and experience what it felt like to trapped, unstable, unbalanced.”

There are many unexpected features within the Jewish Museum of Berlin. For one, the large staircase doesn’t lead into the main auditorium, as might be expected. Instead, it leads up to a blank wall. Visitors must then make a sharp turn in order to enter the main hall. “I did this to show people that some questions can never be answered,” Libeskind said. “After the Holocaust, we’re tempted to give answers and explanations, to shed light on such gaping questions. But no mater how much time passes, some questions can never be answered. The Holocaust will forever remain a challenge to humanity—a question that, in the end, faces a blank wall.”

Libeskind’s favorite project was not one of his largest or most well known. It’s the Felix Nussbaum Museum, located in Osnabrück, Germany. The memorial is dedicated to the Felix Nussbaum, a German Jewish artist who was killed during the last months of World War II. Hiding in an attic, Felix and his wife were exposed by their neighbors and sent on the last transport to Auschwitz.

“We can’t understand six million,” Libeskind said. “But we can understand one man—one regular person whose life was torn apart.” The museum is divided into three sections. The first is make of wood, representing Nussbaum’s life before the war. The middle section is made of metal, signifying the gradual descent into chaos, he explained, and the final section, made of concrete, has no windows and no clear exit.

“The exit is purposefully left unmarked, because for Felix, there was no exit,” Libeskind said. He recalled a conversation he had with some visitors when the museum first opened. “They turned to me, not knowing I was the architect, and asked me where the exit was. I told them I had no idea.”

After the presentation, Libeskind took questions from the audience. One questioner inquired into the connection between music and architecture.

“A profound question,” Libeskind answered. “Architecture, just like music, speaks more to the emotions than to anything else. Architecture today underestimates the human mind. It tries to push neutrality. I hate neutrality. Neutrality breeds apathy. And it’s only when we no longer care that hope is lost.”

Previous: Daniel Libeskind Design Mocked in Mock-Up

D.C. Museum Promises Libeskind, Holograms

Daniel Libeskind Goes Prefab

Hannah Dreyfus is an editorial intern at Tablet.