Despite Unrest, Hasidim Head to Ukraine

Security concerns won’t derail annual Breslover pilgrimage to Uman

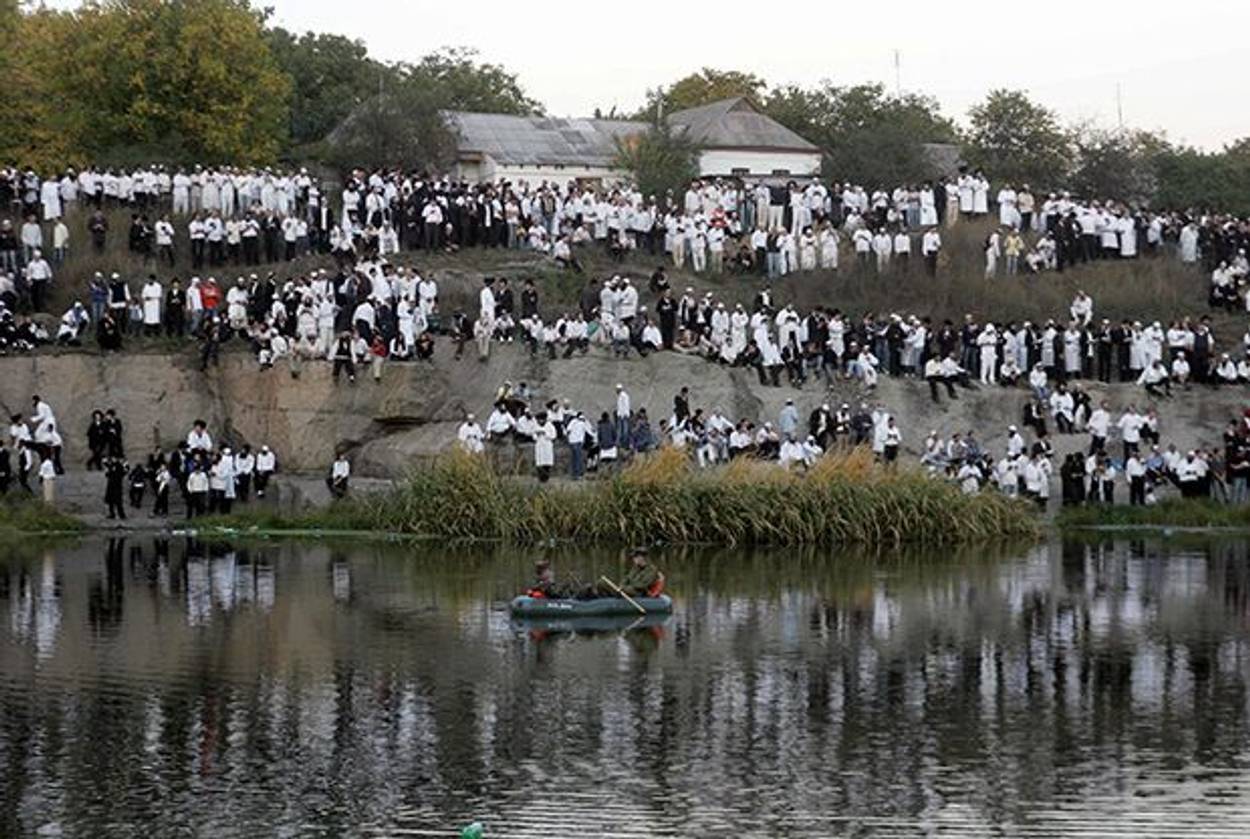

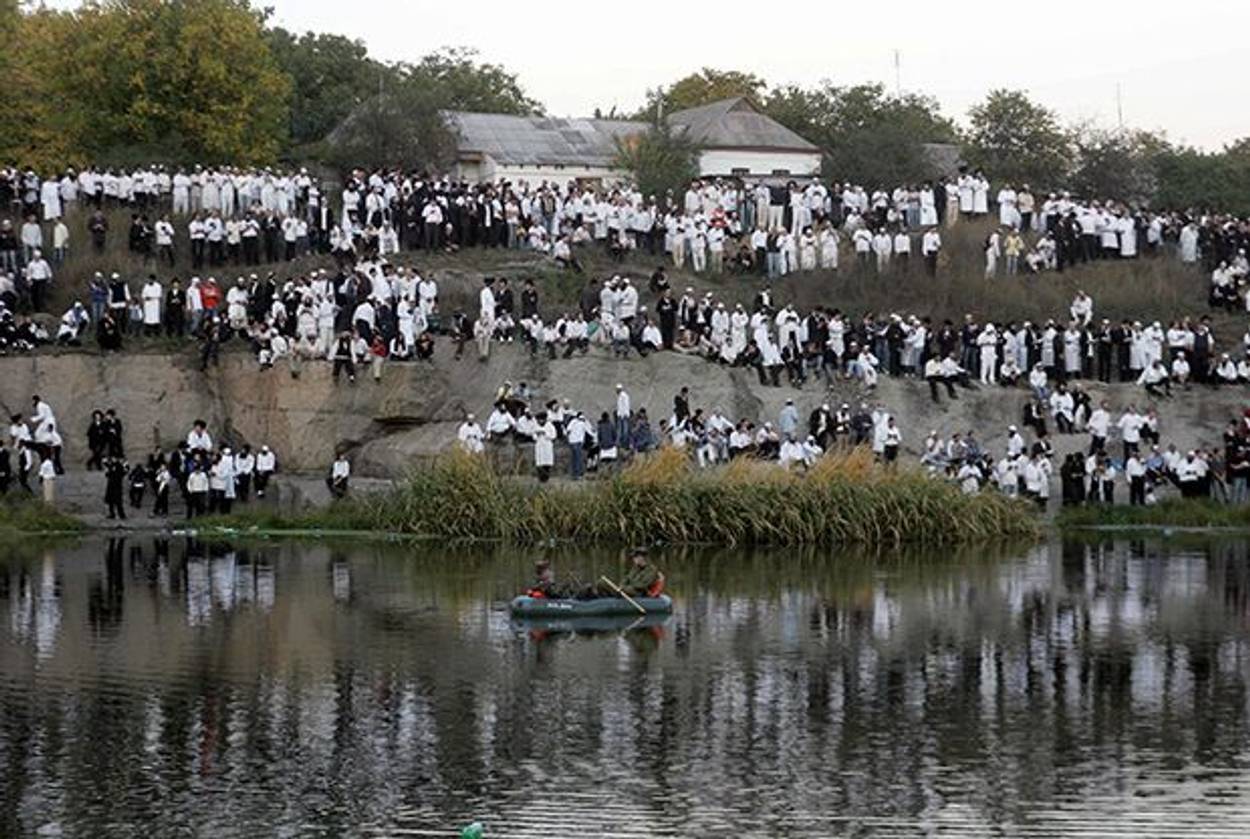

In the days and weeks leading up to Rosh Hashanah, Breslov Hasidim from around the world—most notably strongholds in New York, Israel, the U.K. and Canada—travel to Uman, a small city between Kiev and Odessa in Ukraine, to spend the holiday near the grave of their spiritual leader, Rebbe Nachman. In the years since the fall of the Iron Curtain, Rosh Hashanah in Uman has become a veritable institution often compared to a Hasidic Burning Man, complete with exuberant dancing and a variety of expressive coifs.

Between 30,000 and 35,000 pilgrims, mostly men, are estimated to have made the journey last year, up from 1,000 in 1989, the first year access to the gravesite was allowed. Despite some relatively minor discord with locals––Uman has a permanent population of around 85,000––most years have gone so smoothly that a kind of cottage tourist industry geared towards the Hasidim has grown around the holiday: Kosher food tents are erected, souvenir vendors set up shop, and medical personnel organize a makeshift emergency clinic, as the nearest hospital is in Kiev, a three hour’s drive away.

But even with this infrastructure, devoted Uman-goers have voiced concerns about traveling to a country that has seen serious internal strife over the past eight months. In February, peaceful demonstrations in Kiev ended in fatal clashes between anti-presidential protestors and police. Since then, fighting between pro-Russian rebel factions and those who favor a separate Ukranian state has erupted in the eastern part of the country, as well as the Crimean Peninsula; the occasional cease-fires have been short-lived. Perhaps most harrowing of all for travelers is the specter of the Malaysia Airlines Flight 17, which is widely believed to have been shot down by pro-Russian separatists, killing all 238 passengers on board.

“It would be foolish to pretend that this year is no different than the last few years,” said Motty Zeitlin, a 37-year-old salesman from Monsey, N.Y., who has been spending the holiday in Uman for more than two decades. Dovid Sears, a Brooklyn-based author and translator, tentatively echoed Zeitlin’s worry. “I’m sure we’re all a little bit nervous about it,” he said, adding that his grandson was flying via the Russian airline Aeroflot. “We’re all anxious about how these planes are being routed.” Neither Sears nor Zeitlin, though, has allowed the threat of violence to disrupt his plans. Both are planning to stay in Uman for around a week; Zeitlin is bringing along his two sons, ages 8 and 14. Resolute pilgrims seem to be the majority: Haaretz reported that 20,000 Hasidim were scheduled to make the trip from Israel. Add to that figure the number of prospective travelers from the United States alone, and one can safely guess the gathering will be nearly as big as it has been in recent, more peaceful years.

During his lifetime, Rebbe Nachman of Breslov, whose spiritual philosophy focused on nurturing joy and engaging in private, meditative prayer, preached often on the importance of Rosh Hashanah. He began encouraging his followers to spend the holiday with him when he was still alive, and stressed that they should continue the tradition after his passing. “With practically his dying breath, he spoke about going to him for Rosh Hashanah,” said Sears, who has written essays and books on Breslov philosophy. “Rosh Hashanah is the yom hadin—the time of judgment—and we have this belief that our traveling to the Rebbe’s burial place is something which is very efficacious in mitigating harsh judgments against the Jewish people.”

Many of those preparing for the journey list faith as their ultimate source of guidance and protection. Ozer Bergman of Jerusalem said that he has “no hesitation whatsoever” about his upcoming trip. “With what I know about the Rebbe’s Rosh Hashanah, its personal, national and eschatological value, I’m not about to let some vague possibility of harm get in the way.” Another reason Breslovers say they aren’t afraid is Uman’s distance from the locus of the fighting. Almost smack in the center of the country, Uman is an eight-hour drive away from the Crimea, and even further from Donetsk and Luhansk, the eastern provinces where Russian forces are particularly active. Rabbi Chaim Kramer of Israel, founder of the Breslov Research Institute, says he visited Uman several times over the summer and “didn’t notice anything different.”

The American Embassy in Kiev stated that they don’t know of any specific Uman-related concerns, but that “the situation is very fluid and it is difficult to predict further developments in the country.” They added that foreigners “should definitely exercise special caution” when traveling in the region. Travel agents who organize trips to Ukraine have gone so far as to cancel tours for the foreseeable future. “Right now, we don’t recommend that people go to the country as a whole,” said Mariana Fisher, an agent with Exeter Travel Group, which has been arranging Central European travel for twenty years. “The situation is too unstable.”

The idea of being in danger in Eastern Europe sparked too many fears for some would-be pilgrims. After having spent the last eight Rosh Hashanahs in Uman, Simcha Goldberg of Woodmere, New York, decided to stay home this year. “It was [my wife’s] idea for me to go in the first place. With the war this year between Russia and the Ukraine, she told me that she is not telling me what to do, but that if I go she won’t be able to sleep or rest until I get home. My wife’s parents were Holocaust survivors and I just couldn’t put her in such a state of worry.”

Kelsey Osgood has contributed to The New Yorker, Time, and Salon, and is the author of the book How to Disappear Completely: On Modern Anorexia.