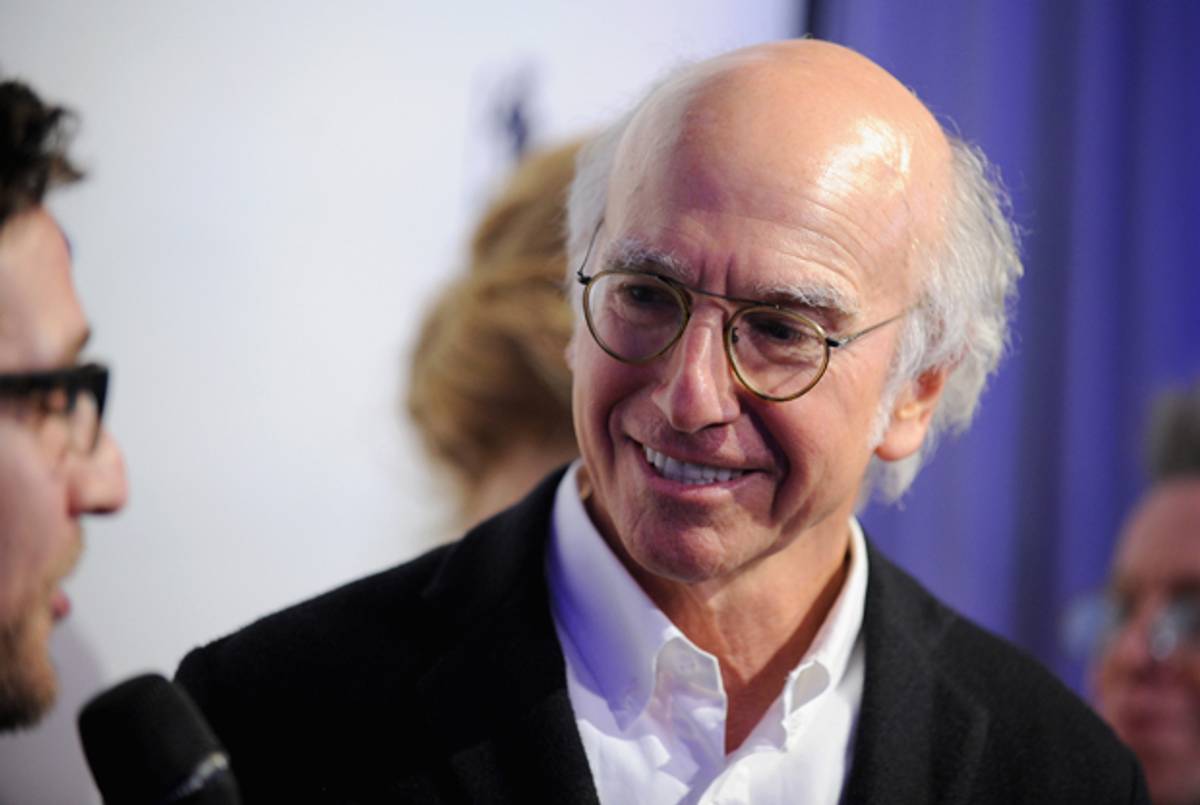

If you enjoyed Seinfeld in the 1990s and Curb Your Enthusiasm in the past decade—both the watching of episodes and the inevitable quoting and referencing that follow—it’s likely that your sense of comedy, and perhaps your attunement to social etiquette, has been influenced by the vision of Larry David.

Anna D. Shapiro, the Tony Award-winning director at the helm of David’s new Broadway show, Fish in the Dark, which begins performances at the Cort Theatre Feb. 2, is well educated in the school of David. “He’s been really formative in the culture of my humor,” she said. That familiarity contributed to what she called a “shared space” as she and David began to develop and rehearse the play, which marks David’s entry into professional theater as both a writer and actor.

In the past five years, Shapiro has become a go-to director for plays with notable screen actors who are newcomers to Broadway (this past year, she directed James Franco and Michael Cera). Working with David is a natural fit for her, particularly considering her affinity for his shows. Still, Shapiro knew that too much admiration on her part wouldn’t serve the work.

“You can’t get too enchanted,” she explained. “You have to be able to step back and look at what is working and what doesn’t work.”

Basically, Shapiro had to take her reverence and curb it. Fortunately, her collaborator is an artist for whom irreverence is a creative goalpost. On Curb, the semi-autobiographical HBO series created by and starring David, there is no reverence to be found anywhere: not for any living person in David’s orbit, and certainly not for the deceased. The show’s inherent dark comedy gets one shade darker every time an episode depicts terminal illness or death. It seems to conjure Samuel Beckett’s maxim, “Nothing is funnier than unhappiness.” Yet on Curb, it’s not so much that death is funny, but rather that the sobering and tragic events are paired with outlandish responses and behavior.

True to form, the opening scene of Fish in the Dark depicts a family gathered around the bed of a dying relative. It’s not an amusing situation in the least. And yet, Shapiro said, “in every run-through we’ve done with an audience, people fall out laughing.”

Perhaps that’s the effect of a comedian who can make an audience start to laugh before he even says a word. “He’s such a complete presence,” Shapiro explained. “He’s framed his character so well that just the sight of him is funny. And it is a character.”

In recent interviews, David has revealed very little about the play. Shapiro sees the element of secrecy as a way for audiences to come in without specific expectations beyond seeing David’s narrative style in a live space. Because David also stars in the show, it was essential to Shapiro that he find a comfortable presence to suit his character. David, who in one rehearsal admitted to Shapiro, “I figured out something about my acting: I like leaning and sitting,” had to become acclimated to movement onstage, and Shapiro advocated for several script changes to encourage it further.

As Shapiro advised, a scene at a shiva should not occur entirely in the living room where people are seated. “Everyone’s on their best behavior in the living room,” she explained regarding her suggestion to move that scene to a different physical space, somewhere less predictable and more dramatic.

Fish in the Dark isn’t the first time Shapiro has helped a famous comedian find his stage legs. Chris Rock made his theater debut under her supervision in Stephen Adly Guirgis’ 2011 play, The Motherfucker with the Hat. Rock and David are hugely successful performers, and both faced hurdles as well as advantages in the rehearsal process.

“Chris was coming into a new play that he didn’t write, playing a character that he would not normally play,” Shapiro recalled. “But, he does a lot more stand-up than Larry. So where the learning curve was really steep, another part was not. With Larry, it’s the mirror image. He’s playing a character he’s very comfortable playing and with language he wrote. And yet, he doesn’t do stand-up anymore, so he’s in a relationship with the audience that’s very new.”

Another new experience for David is having to rewrite his script in and out of rehearsal. That’s certainly a change from Curb, which has no formal script at all and largely relies on improvisation. Shapiro explained of the process, “there are spitball changes, like ‘take that out, try this instead,’” as well as bigger structural changes that involve late-night brainstorming between writer and director.

Anyone who has regularly watched Curb during its eight-season run knows how important narrative structure is to David. The show is more than a series of vignettes about the trappings of social propriety—every thread introduced at the start of an episode not only has dramatic payoff by the end but also converges with the episode’s other story arcs. In that sense, Curb is close to dramaturgically perfect. Don’t be fooled by the show’s ad-libbing: David is a writer who understands form.

Compelled to create a longer narrative work following the death of a friend’s father, David wrote what Shapiro described as “a well-made play”. Like Seinfeld and Curb, Fish in the Dark has a main character, but is at its heart an ensemble piece. “There are great moments when you feel like Larry is this master and he’s standing there and something is unfolding that’s so unbelievably funny that his character is observing,” she said of David’s role on Curb. Part of creating an ensemble, Shapiro explained, is “giving the best lines to other people”. The play’s cast includes Rita Wilson, Ben Shenkman, Rosie Perez, and Jerry Adler, as well as several other actors.

The ad-libbed dialogue that exemplifies an auteur-based show like Curb, however, is risky for a Broadway play, and Shapiro admitted it was a major concession to allow improvisation in Fish in the Dark. In certain pre-approved scenes, “Larry and his scene partner know what the [moment] has to include as well as their cue for getting back to the script,” Shapiro said. Though in one rehearsal, David told her, “I just want you to know, if I’m getting big laughs, I’m gonna keep going.”

It’s possible—and perhaps likely—that audiences will come to Fish in the Dark hoping for such an improvised moment. But ultimately, Shapiro said, the play aims for something bigger: a cohesive story about family and loss, told through David’s comic lens.

“Somehow he strikes that balance,” Shapiro said. “He finds that narrow ledge that allows you to look at really painful things and just see how ridiculous and human and shared the experience is.”

Previous: Larry David Writes Broadway Play About Shiva

Related: Unrepentant

Lonnie Firestone writes about theater, and lives in Brooklyn, New York.