Don’t Return the Iraqi Jewish Archive

Iraq wants the treasures of a Jewish community it persecuted to extinction

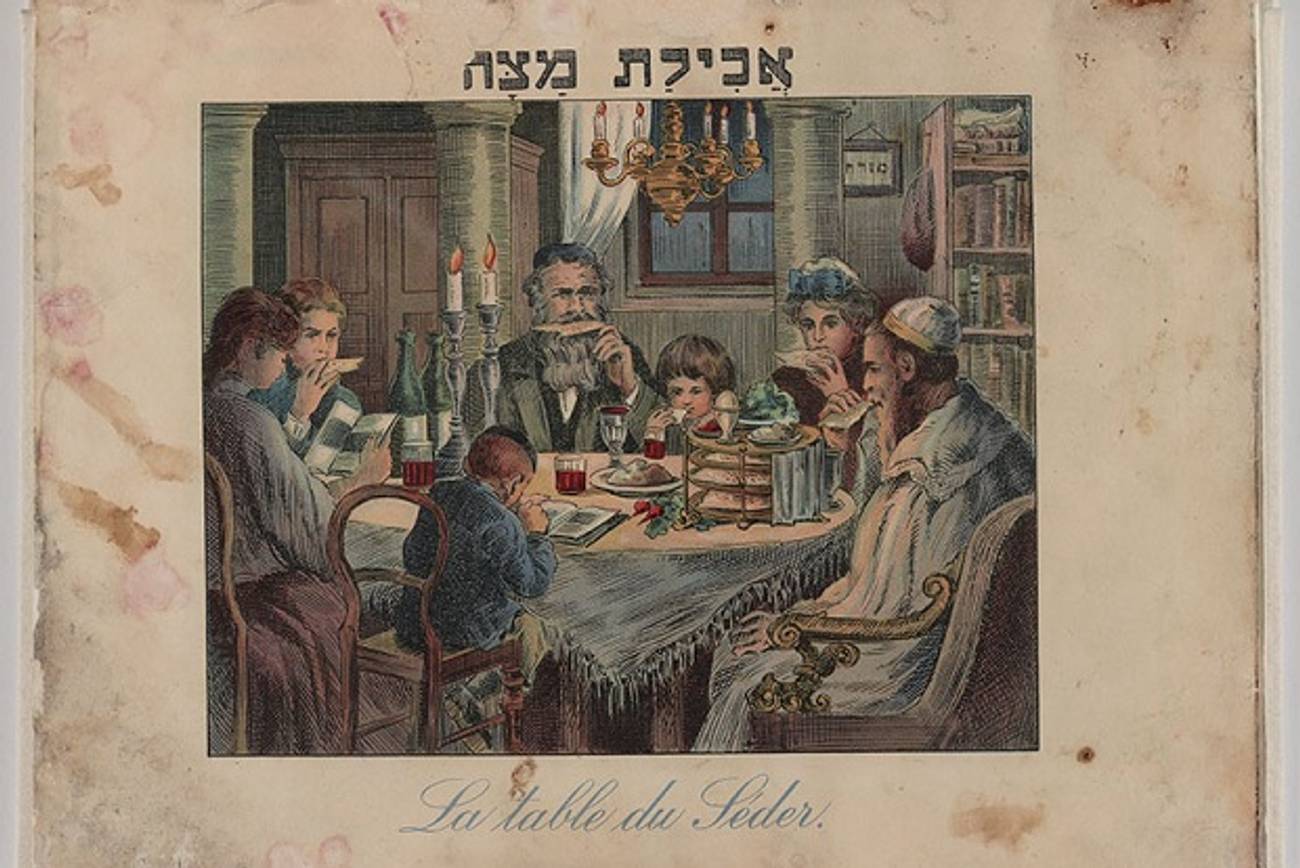

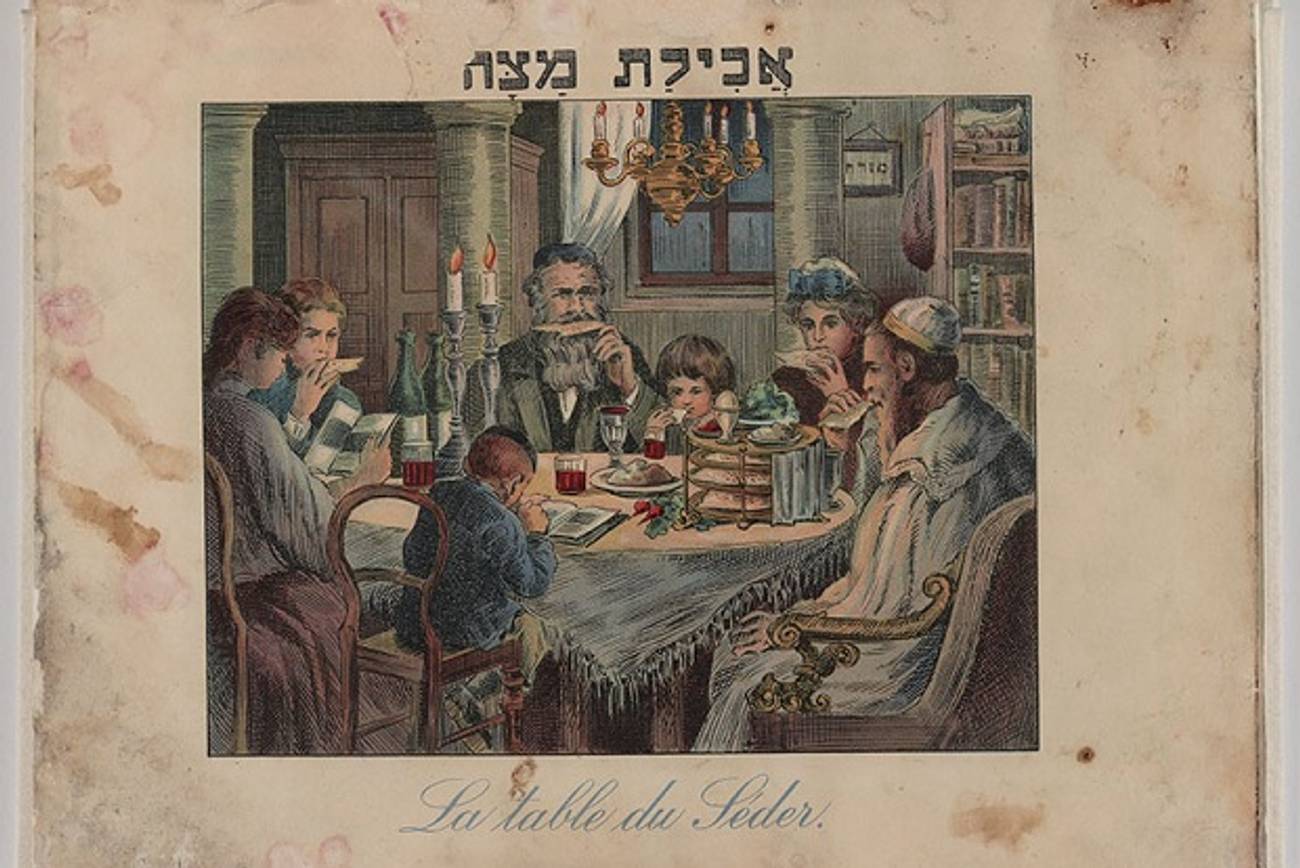

On May 6, 2003, American forces stumbled into the basement of a flooded Iraqi intelligence building in Baghdad. There, they discovered a veritable treasure trove of Jewish holy books, communal records, and even family photographs. The contents of the archive were salvaged, and–with the help of U.S. government funding and outside donors–restored in a painstaking $3 million dollar process. The resulting exhibit ran at the National Archives in Washington D.C. from November 8, 2013 through January 5, 2014. But now, in accordance with a 2003 agreement with the Iraqi government, these priceless Jewish artifacts are set to be returned to the country where they were found.

Jewish organizations, working with Democratic Sen. Richard Blumenthal and Republican Sen. Pat Toomey, have protested this move, and asked Congress to intervene. Legislation calling for renegotiating the archive’s return now has 10 co-sponsors in the Senate. That resolution has begun to receive some press attention, but its cause deserves more than media coverage: it deserves public outrage. Simply put, the Iraqi government has no just claim on these Jewish artifacts, which were stolen from its Jewish community as they were persecuted to extinction during the 20th century.

To understand how morally obtuse it would be to return the archive to Iraq, a brief history lesson about its treatment of its Jews is in order. This past Monday marked the 45th anniversary of the public hanging of nine Jews in Baghdad on trumped up charges of espionage. The event was essentially the epitaph for Iraq’s once-proud Jewish community. The oldest diaspora Jewish community in the world, Iraq’s had numbered 150,000 strong. But after decades of persecution, it would largely be wiped out, with only a token handful remaining. As a recent post at the Israeli National Archives recounts in painful detail, this death spiral began in the years leading up to Israel’s establishment, when Iraqi Jews became scapegoats for the Jewish state’s independence, and the Iraqi military’s failure to prevent it:

The Iraqi government started to implement discriminatory measures against Jews in accordance with a law drafted by the political department of the Arab League. Jewish civil servants were fired, …Jewish banks were not allowed to change foreign currency, and new and heavier taxes were imposed on the Jews. Jews were not allowed to leave Iraq for more than a year and those that left had their property confiscated and their citizenship nullified. In September 1948, a rich Jewish businessman, Shafiq Ades, was hanged under false accusations. The persecutions caused many Jews to secretly cross the border to Iran and from there escape to Israel. In December 1949, Tawfiq al-Suwaidi replaced Nuri el Said as Prime Minister, and conditions became easier for the Jews. After a secret negotiation with El-Suwaidi, Jews were allowed to leave Iraq without hindrance, and 120,000 of the Jews in Iraq chose to come on Aliyah to Israel in Operation Ezra and Nehemiah.

Matters did not improve for the remnant that stayed behind, and reached their nadir after the Six Day War in 1967, in which Israel humiliated the combined militaries of its Arab neighbors, including Iraq:

The Iraqis vented their frustration from the results of the war on the Jews of Iraq: Their telephones were disconnected, Jews were fired from their jobs, shops under Jewish ownership were closed, and Jews were barred from traveling from one city to another. Leaving Iraq, banned already before the war, was now impossible. The small Jewish community lived in constant fear.

The post-Six Day War feeding frenzy culminated in the arrest and public execution of nine innocent Iraqi Jews in 1969. Thousands of onlookers danced in Baghdad’s central square while the bodies dangled in the wind. Witnessing this lurid spectacle, Israeli Prime Minister Levi Eshkol said, “The hangings have illuminated the fate of the remnants of the Babylonian Jewry with nightmarish light. The land of Iraq has become one great prison for its Jewish remnants. Our brethren are prey to terror in the hands of villains.” By the time America invaded Iraq in 2003, less than a hundred Jews remained.

The Iraqi Jewish archive, in other words, is all that remains of a community that was viciously hounded to extinction. The holy books and other documents were found in a government building not because Saddam Hussein was a closet Talmudist, but because they were either stolen from or abandoned by their rightful owners. As New York Times critic Edward Rothstein put it, “the collection’s state of ruin is an uncanny representation of what happened to the Iraqi Jewish population itself.”

Today, there is almost no one left in Iraq to appreciate the Torah scrolls fragments, kabbalistic works, and other rare gems found in the collection. But outside Iraq, there is a thriving Iraqi Jewish community in Israel and abroad. These descendants deserve to have their possessions returned to them, or at least made readily accessible, not put on display in a Baghdad museum where no Israeli can safely visit.

What happened to the members of Iraq’s venerable Jewish community was a tragedy of profound proportions. Let’s not compound it by abandoning the best historical witness to the lives they led, the treasures they kept, and the world they lost.

Yair Rosenberg is a senior writer at Tablet. Subscribe to his newsletter, listen to his music, and follow him on Twitter and Facebook.