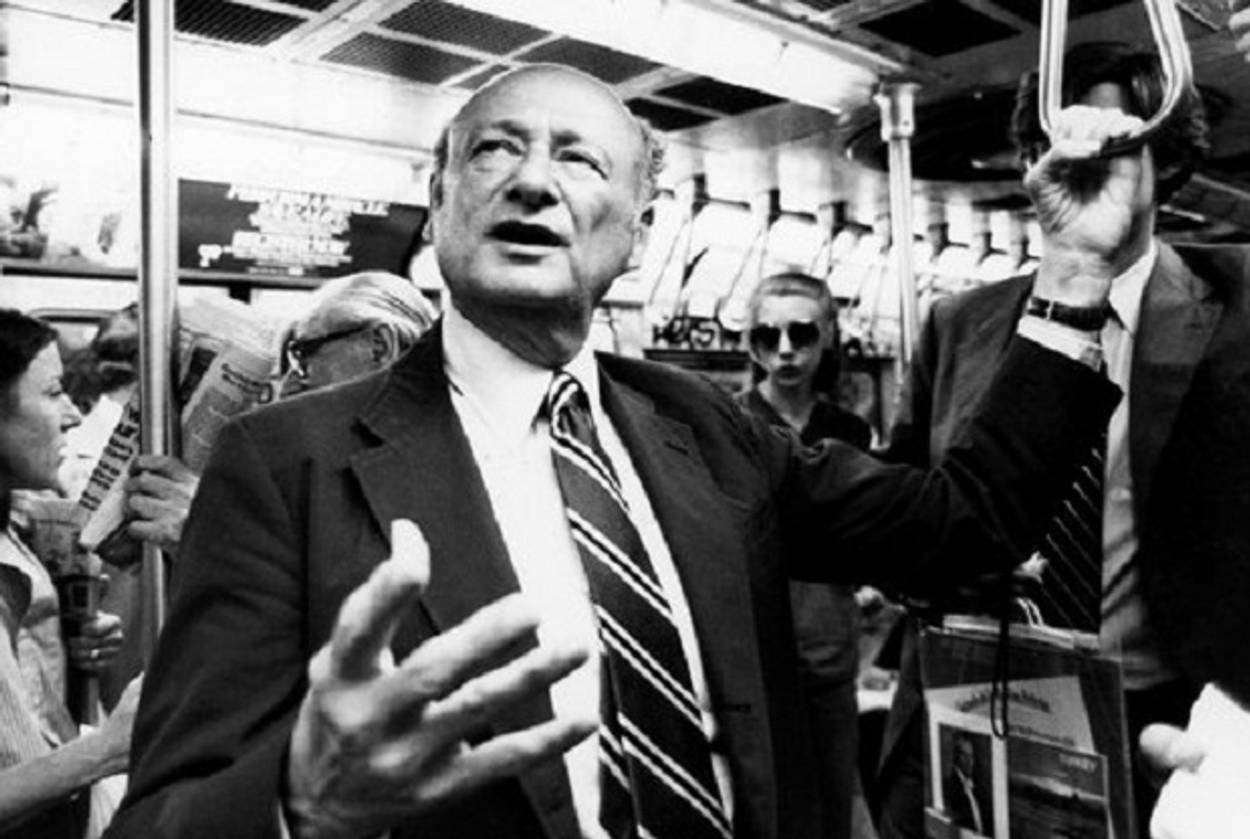

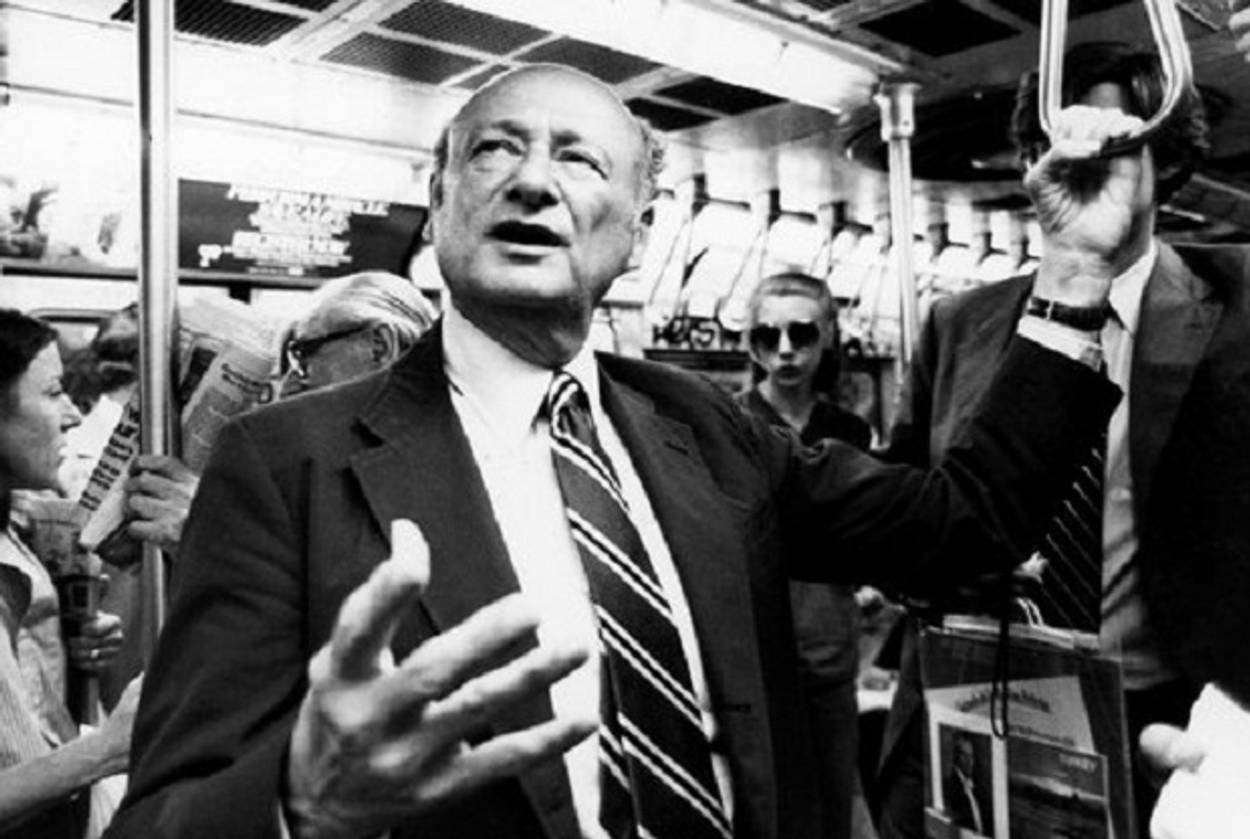

Ed Koch ‘Not Liberal Enough for the West Side’

An excerpt from Stars of David: Prominent Jews Talk About Being Jewish

In 2005, Abigail Pogrebin published Stars of David: Prominent Jews Talk About Being Jewish. The following is an excerpt from the chapter about Ed Koch, the former mayor who was buried today in New York City.

Edward Irving Koch grew up in Newark, New Jersey, and attended the Hebrew Free School. “The teaching was terrible,” he says. His father, Louis, was a furrier, and his mother, Joyce Silpe, was a “terrible cook.” She burned everything,” he says with a laugh. “And my father loved everything to be burned. I like rare food. I like it bloody.”

He says his mother was determined to assimilate. “She hired a tutor to teach her to lose her Yiddish Central European accent.”

In his last year of college, he was drafted into the army, where he “had a fight because I was a Jew.” It all started because his platoon, according to Koch, was composed of twenty-five percent Jewish New Yorkers. “It was an unusual number,” he says, “and many of them simply couldn’t do the obstacle course. I must say, I found it hard, but I practiced. I wanted to look good. What the Jewish kids did excel in was asking questions. So when they had seminars, the Jewish kids would put up their hands and ask questions. And one day, this one guy said, ‘Which is the next Yid that’s going to ask a question?’ I knew I couldn’t take on a fight because I wasn’t strong enough yet— this happened in the first few weeks of basic training. So I said, ‘I’m going to build myself up and ultimately I’m going to challenge him.’”

Koch trained hard over the next sixteen weeks. “It didn’t help,” Koch admits with a smile, “he still beat me up. But I was proud of the mere fact that I challenged him. I went over to him and grabbed him by the throat and I said, ‘We’re going to have it out.’ And he said, ‘Why? What did I do?’ And I couldn’t say to him, ‘It’s because of what you said.’ He looked baffled, but all I could say to him was, ‘You know. You know.’”

I wonder if, once Koch got to be the blustery, bigheaded, likable mayor of New York, he became more Jewish on the job than he had been. He nods. “Sure. It made me speak out more. I am very proud of the fact that, as a result of being identified as proud of my faith, I got higher percentages of Catholic votes than I got from the Jews.” Like most dyed-in-the-wool candidates, Koch rattles off numbers: “Eighty-one percent of the Italians and the Irish supported me in my elections, whereas with the Jews, it was only seventy-three percent, and the reason is very simple: I’m not liberal enough for the West Side Jew. And I’m proud of that! I am a moderate! Jews have a very large group that is too radical for me in a host of areas. But the Catholics love me. I’m proud of the fact that John Cardinal O’Connor asked me to do a book with him. It was called His Eminence and Hizzoner.”

Koch makes sure to attend synagogue on the High Holy Days every year, though he never had a seder at Gracie Mansion. “But I put up a mezuzah on the door there,” he points out. “Abe Beame had a mezuzah.” (He refers to a famous predecessor.) “But I had a better mezuzah. And when my father died, we sat shivah at Gracie Mansion. That was nice.”

When I ask him if he feels more Jewish or more American, he winces. “It’s not a question that should be asked. Look, I am an American. I happen to be a white male, a senior citizen, and I’m Jewish. If I had to pick the two things I’m proud of, it’s being an American and being a Jew. But my overall allegiance is American.”

Koch pulls out an anecdote to illustrate: “When I was a congressman, early on, I noted that they had prayer breakfasts in Washington every two weeks, where a group of legislators would meet for breakfast and discuss religious matters. One day, a congressman from Mississippi, Sonny Montgomery, meets me on the House floor and says, ‘Ed, next week we want to discuss Judaism. You are a Jew?’ ‘Yes, I am a Jew.’ ‘Would you come and lecture on Judaism?’ I said, ‘Sure.’ At the time, I thought, ‘I’m not a scholar, how much do I know? I’ll go to the library and figure out what will amuse them.’ I took out a couple books, read them, and went to the breakfast. And I told them about Jewish exotica, which they enjoyed, and then they asked questions. At the end, I said, ‘What’s interesting to me is you are all avoiding a question which I know is on your minds by looking in your eyes. And the question that you’re not asking me is, “Do Jews have dual loyalty?” Isn’t that what you’re wondering?’ They all nodded. ‘So I want to make you one pledge,’ and I raised my right hand. ‘I swear to you, that if Israel ever invades the United States, I shall stand with the United States.’ And they roared.”

But Koch does have a deep fealty to Israel that clearly makes him hyper-aware of when it’s the target of condemnation. “It’s clear to me that anti-Semitism has re-arisen to an extent even greater than before World War II, without the killings in concentration camps,” he says. “I don’t want to overstate it, but I mean, it’s amazing— the hate and the venom. It’s directed at Israel because it wouldn’t be acceptable in polite circles to direct it at Jews, but it’s intended to be directed at all Jews.”

I ask how he would explain this Jewish hatred. “First: anti-Semitism is based, in large part, on actions of the church; and we’re very lucky there have been popes who have changed that to an enormous degree. But take Cardinal Glemp in Poland. I met him; he is a vile anti-Semite. And he’s the primate—the number one cardinal. So in Europe in particular, you have still the residue of that.

“Second is: We’re supposed to be dead! ‘Why are you still standing?!’ There’s a certain resentment: ‘How could it be? We’ve kicked the shit out of them; why are they still standing?’”

Excerpted from Stars of David: Prominent Jews Talk About Being Jewish by Abigail Pogrebin. Copyright 2005 by Abigail Pogrebin. Used by permission of Broadway Books, a division of Random House, Inc.

Abigail Pogrebin is the author of Stars of David and My Jewish Year. She moderates the interview series “What Everyone’s Talking About” at the JCC in Manhattan.