Fifty-seven years ago this month, a Jerusalem District Court pronounced its verdict in the trial of Adolf Eichmann. The court case changed the way Israelis viewed the Holocaust and led to its wider study. Gabriel Bach was one of three prosecutors at the trial. Accompanied by professor Keith Nunes, the director of the Institute on the Holocaust and Law at Touro Law Center, I visited Bach at his Jerusalem home this spring. Daily, he told us, he is reminded of the trial—more than any other case he worked on. Here are some of his stories.

Gabriel Bach was born in Germany in 1927. He attended the Theodore Herzl School, located on Adolf Hitler Square in Berlin. His family moved to Holland in 1938, two weeks before Kristallnacht. They left for Palestine one month before the German invasion of Holland, sailing on the Patria, (which was sunk in Haifa on its next voyage). Bach came to serve as Israel’s state attorney, and later as a justice on the Supreme Court, retiring 21 years ago.

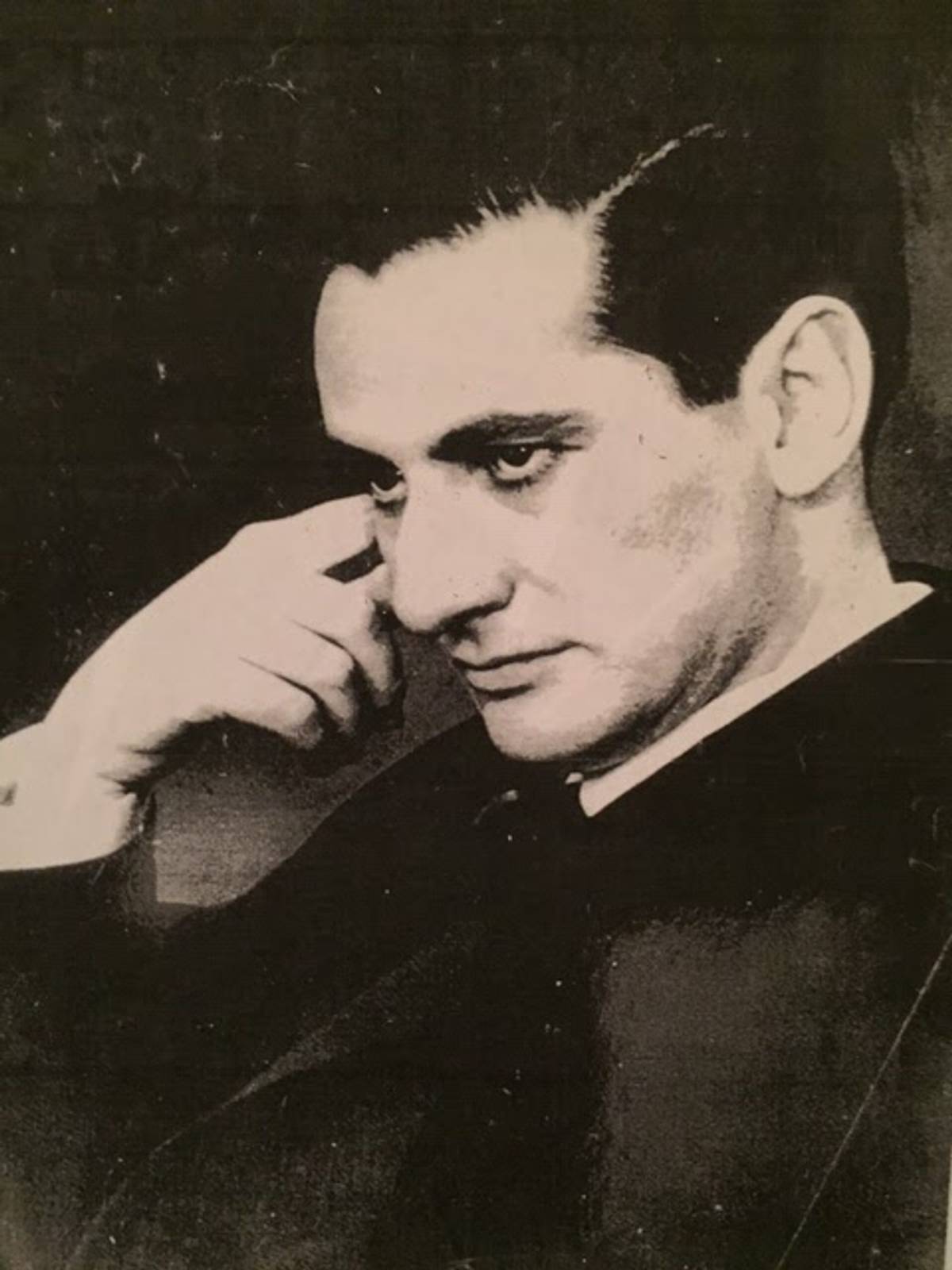

Justice Bach as a young boy

During the two-year Eichmann trial, Bach served first as legal adviser to the police who gathered evidence and then as a prosecutor. The German government cooperated in providing documents from Eichmann’s wartime correspondence. Bach as a prosecutor was responsible for presenting the evidence from several countries. One was Hungary, where he emphasized the following telling episode.

In 1944, Hungarian leader Admiral Horthy wished to leave the Axis to make a separate peace with the Allies. Hitler came to convince him to stay in. Horthy acquiesced, but one of his conditions was that 8,700 Hungarian Jewish families be allowed to emigrate to a neutral country. Hitler conceded because he could thereby deport the legions of other Hungarian Jews. The prosecution found a telegram from the Nazi appointee in Budapest to German Foreign Minister Ribbentrop, reporting that Eichmann, then in Hungary, was very upset about these families, saying they were important “biological material,” who could proceed from the neutral country to Palestine, where they could help reconstitute the Jewish race. According to the Nazi telegram, Eichmann tried to speed up deportations so those Jews would be taken before their visas came. Eichmann thereby acted in defiance of Hitler himself, belying his claim of just following orders.

Documents from various countries showed Eichmann was often requested to spare particular Jews. However, to Bach’s surprise, no matter how seemingly strong the request, Eichmann invariably said no.

From Paris, a German general wrote to Eichmann requesting he spare professor Weiss, an expert on radar, for his war value. Eichmann refused. When the general replied saying, “How dare you refuse me, I am a General!” Eichmann responded, “And I am a SS-Obersturmbannführer (Lieutenant Colonel), and I understand you already took over his patents, so there is no need to delay his deportation.” When the SS came, professor and Mrs. Weiss managed to drop off their infant daughter at their neighbors, who sent her to America. During the trial, this young woman came to Israel and visited Bach in his office. She said she had no memories of her parents, and asked Bach to help her locate photos. He tried unsuccessfully.

In Lithuania, the Germans arrested a Jewish woman who was the widow of an Italian war hero. This Italian officer had died fighting the Allies with the Germans. The Italian ambassador to Lithuania asked Eichmann to spare her, saying that, “All of Italy feels this lady should be allowed to return,” and “the Italian authorities demand her return, in memory of her husband.” Eichmann refused and sent her to the camps.

In Holland, the Dutch Fascist leader requested Eichmann spare a dozen or more Jewish Dutch Fascists, on the grounds that their deportation would demoralize their party comrades, and because they could help identify other Jews. Eichmann agreed only to delay their deportation to Auschwitz for two weeks. After that, Eichmann said, their comrades would be used to it.

A judge asked Eichmann during his trial what he thought of the Holocaust? He responded that it was a great crime. The judge and press later asked Bach what he thought of this response? Bach replied that it was lip service to save his life, especially since Eichmann had told an interviewer in 1956 that his “one regret was that he had not been tougher, and had fought the interventionists more because now you see what has happened, the Jews have reconstituted their State.” That was 11 years after the war, and five before the trial. Therefore, Bach said, he felt justified in not believing him for a moment.

Eichmann designed an array of psychological manipulations, to help keep the Jews unsuspecting on their path to destruction. On such device was forcing arrivals at Auschwitz, moments before being sent to the gas chambers, to write postcards to their relations. Eichmann determined what the content of these postcards would be, such as: The conditions are good here, come before all the places are taken.

During the trial, a survivor was identified who had received such a postcard, and had subsequently come to Auschwitz with his family. This witness came to Jerusalem the night before he was to testify. They translated the postcard from Hungarian to Hebrew, but it was already 11 o’clock at night, so Bach told him to come to his office in the morning. However the witness arrived late the next morning, and Prosecutor Bach had to put him directly on the stand, without having heard his story.

The witness testified of how he arrived at Auschwitz on the train, with his wife, 12-year-old son, and 2 1/2-year-old daughter. The guards told his wife and daughter to go to the left, which he later learned were the gas chambers. Telling the guard he had been a metal worker in the army, he was told to go to the right. However, the guard was uncertain where to send his son. They waited some time until the guard returned and told his son to “run along after Mama.” The son went off to the left, and the father stood there trying to see if he would find them. But meanwhile hundreds of people had gone between them, and soon the father could not see his son anymore, nor could he distinguish his wife in the distance. But his young daughter was wearing a red coat, which he was still able to spot. He watched this red dot get smaller and smaller, and so his family disappeared from his life.

Prosecutor Bach himself then had a 2 1/2-year-old daughter, Orly. Two weeks before, they had bought her a new red coat. The very day before, Bach’s wife had photographed the red-coated Orly and him together. Upon hearing the testimony, Bach was unable to speak—he could not force a word out! The judges urged him to continue, but he could only shuffle his papers for three minutes before his voice returned.

After the District Court delivered their verdict, there was an appeal to the Supreme Court, which was heard by five judges. When the sentence was upheld, Eichmann appealed to the president for a pardon. The question arose of when to execute Eichmann, should the appeal be denied? Bach feared that any delay might lead a Jew-hater in the world to kidnap a Jewish child to ransom for Eichmann. He suggested, therefore, that if the pardon is denied, Israel announce it at 11 p.m., and hang him at midnight. That is what happened.

Some years ago, Justice Bach was asked in an Israeli television interview about his childhood in Germany. He recalled attending the 1936 Olympic Games in Berlin, when he was 9 years old. He also had been an avid soccer enthusiast, and the team he liked best was Football Club Schalke 04, because they played great, and because the team’s colors were the same as his Theodore Herzl School’s colors: blue and white.

Three weeks after that interview, some German students were visiting Justice Bach in Israel. They gave him a sport cushion from the FC Schalke 04 soccer team, which they said a deputy of Chancellor Angela Merkel had asked them to convey him in her name.

A few months later, Justice Bach was giving a lecture in Western Germany, and he also told the story of Schalke 04. The moderator said there is someone here who wants to say something to you. A man stands up in the audience and says he is the president of the FC Schalke 04, and that he is here with a number of members of the board, and that they want to present him with some gifts. They gave him a framed photo collage, with team photos from the ’30s and today, and inscribed: The Blue and White will cover us all our lives—in friendship with our dear friend Gabriel Bach. In addition, they gave him a special blue and white Schalke 04 jersey, inscribed Bach.

Judge Bach is surprised by the large crowds of Germans who sometimes come to hear him speak. He is invited to speak to lawyers and other adults, but often when he is there he is asked if he is also prepared to speak to students. He always agrees. Once after a talk to 200 schoolchildren, he received a letter from the headmaster, saying the students came to him and said we want every child to write about what he thought of the talk, and enclosed a sample of 20 to 30 essays. Such things encourage the justice.

Taking out a large manila envelope from his living room drawer, the judge shows us some photos. One is from the courtroom, where we see Bach and others seated at the prosecution table, with defendant Eichmann in the glass box beyond. Justice Bach reflects wistfully that of all the people involved in the trial; the attorney general, the other prosecutors, (Eichmann himself of course), the District Court judges and the Supreme Court judges, he is the only one still alive.

Another photo shows Bach looking reflective with his hand to his cheek. It was taken, he tells us, during a 15-minute break in the trial, and it always reminds the justice of the testimony that immediately preceded the break.

The witness who testified had been a boy at Auschwitz. The Nazis had set up a measuring stick to check children’s height as a quick way of determining who should be killed right away. The boy and his older brother had heard that sometimes the Nazis spared people for a few days for work, but since the boy was short, his brother put some rocks in his shoes and tried to hold him up when they walked past the board. The guards took away his brother for doing this, he does not know what happened to him. He himself, the younger brother, was sent with the other young children to the gas chamber.

When he and 200 other children were locked in the chamber, they started singing together to give each other courage. When nothing happened, they stopped and some started crying. What had happened was a truck had arrived with sacks of potatoes, and since there was no one to unload them, the Nazis thought to take 20 children from the gas chamber to help unload the truck, before they were killed. The boy and 19 other youths were taken out and unloaded the truck. The other children were killed. The 20 were sent to wait for the next group to be killed, but the boy was singled out to be whipped first because they said he damaged the truck while working. The guard in charge of whipping liked him and kept him to work for him doing chores. Therefore he survived.

When the photo of Bach was taken during the break after that testimony, he was thinking of the children singing to encourage themselves, and of how he had never heard such stories. Then he realized that such things may have often happened, but we don’t know about it, because no one survived to tell about it.