Ellen Klages’s Lesbian Time-Travel Novella Is One Hoot of a Genre Mash-Up

In Passing Strange, a Jewish-American artist, a Japanese-American lawyer, a British teen math whiz, and other LGBT women come together in 1940s San Francisco

I knew Ellen Klages only as the author of The Green Glass Sea, a children’s book that won the American Library Association’s award for best historical fiction a few years ago. It’s a thoughtful, beautifully written story about an 11-year-old girl in 1943 who moves to the New Mexico desert to live with her scientist dad, who’s working on the Manhattan Project. I did not know that Klages had a whole other life as a Nebula-Award-winning sci-fi author. And I certainly did not expect to be utterly smitten by Passing Strange, her new lesbian time-travel novella that’s full of torch songs and 1930s pulp comics and drag kings and romance and science and magic and Jewish folklore and great old-school San Francisco Italian pizza and sexy Asian dancers taking advantage of white tourists’ Orientalist yearnings for “a new slant in entertainment.”

Wait, you say. That sounds awesome. And it is!

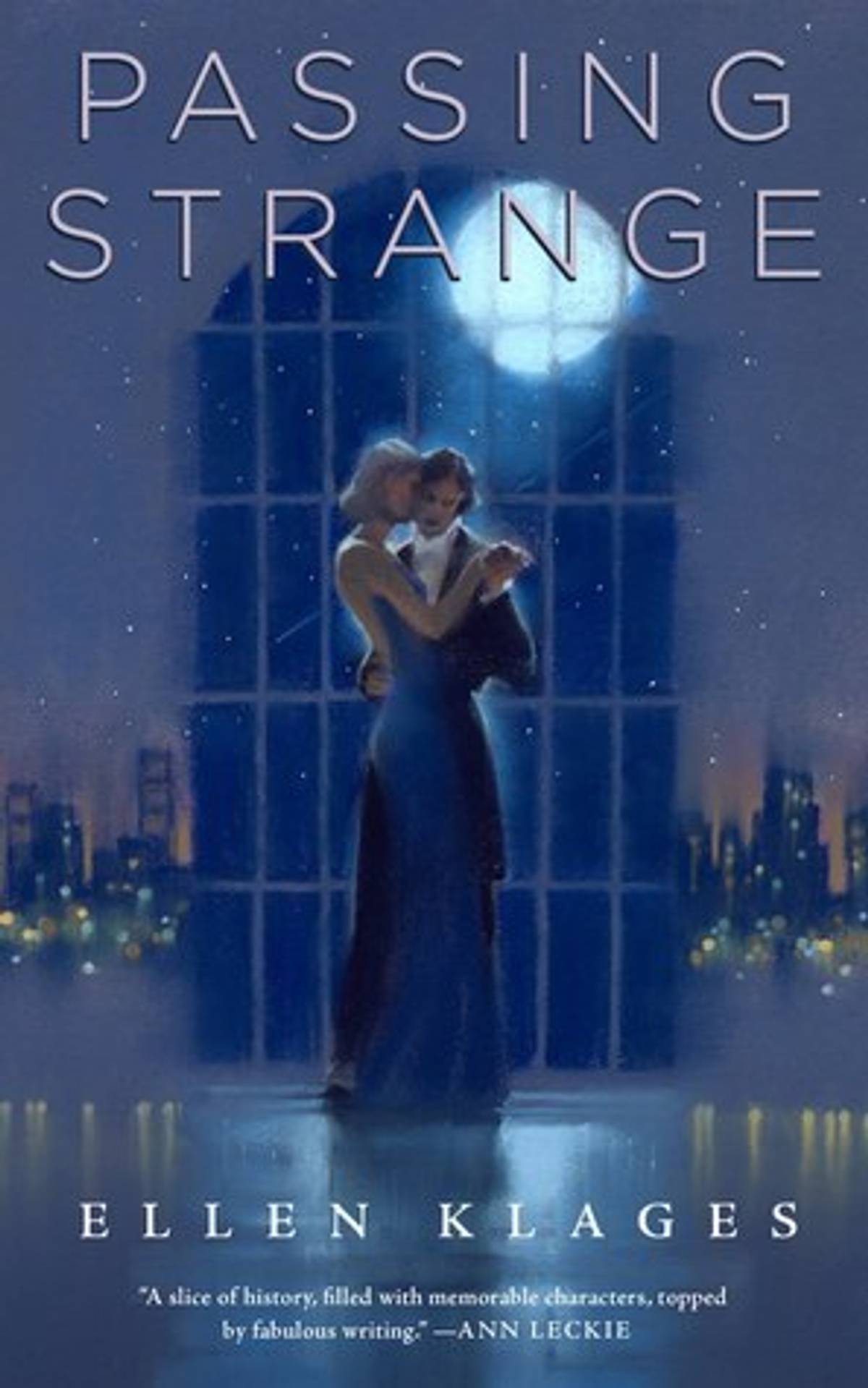

The book opens in the present, with an elderly woman selling a gorgeous, fragile chalk illustration by the legendary artist Haskel to an unscrupulous pulp dealer. “The illustration showed a slender, russet-haired young man in evening clothes, dancing with a woman in a shimmering blue jumpsuit that clung to every curve, her hair a sleek blond waterfall,” Klages writes. “They gazed into each other’s eyes with obvious joy. The dancers stood in a skylit library. Behind them, a wall of windows revealed the skyline of the city and the expanse of the bay spread out below.” (That illustration is on the cover of this book.) The woman then takes the money from the sale, visits a ton of spectacular San Francisco sites and restaurants, distributes the money to charities and gives huge tips to waitresses, and goes home to her swanky Nob Hill apartment and kills herself.

And we turn the page, and we’re in the past—in San Francisco’s lesbian underground in 1940, getting to know a bunch of fascinating women. A coven, if you will. The story centers on Haskel, a bisexual artist who draws sensational, hot-screaming-babe-menaced-by-evil-scientist magazine covers, and Emily, a beautiful cross-dressing young woman from Connecticut who talks like Katharine Hepburn in The Philadelphia Story and who’s been kicked out of college and her family home for sleeping with a classmate. Much of the story takes place in a real lesbian nightclub of the time, Mona’s Club 440. Klages depicts it vividly: “Butches, femmes, Flos, Freddies, wanna-bees, looky-loos, he-shes. At Mona’s, a girl could be anyone she dreamed, even if for just one night, no questions asked. Or at least no answers required.” Like Haskel, we swoon as Emily sings—in her persona as Spike—blues standards that sound like the city at night, “cold drinks and hot neon and people out looking for love, or danger—or both.” Emily’s voice holds “longing and regret, and a little tinge of anger…it spoke to everyone in the room who’d ever had a secret.”

We see both the romance and the danger of being queer at the time—women could be arrested if they weren’t wearing three items of female clothing (even in male drag, women had to be careful to wear women’s underwear and flats or a hidden necklace or a shirt with the label of a women’s store). Women dancing together was illegal. But we also see that the world is deeper and more wondrous than we might imagine. A non-religious scientist puts a mezuzah on her front door. (“That’s religion, not magic,” a character scoffs. “Is there a difference?” replies another.) A cartographer can fold a map to create new routes and shortcuts that evaporate when the paper is burned. A character’s bubbe escapes the pogroms of the old country with the use of an amulet she’s passed down to her granddaughter.

These characters use their otherness to confound expectations, hide in plain sight, and evade those who’d love to destroy them. As a police dragnet closes in on two women in love, art and magic conspire to help them escape.

It’s all delicious. (Almost literally—Klages has a real way of describing food. I was starving by the end of the book.) There are flashes of A Wrinkle in Time and Marlene Dietrich in Morocco and Wong Kar-wei’s In the Mood for Love. I desperately hope some of the peripheral characters will be back in other books—particularly Polly, the 16-year-old genius war refugee (she asks in a huff, “I queried Harvard and Yale, but did you know neither of them accepts women?”) with a magician father and a passion for physics. If you’re a fan of historical fiction, romance, speculative fiction, or LGBT stories—or any permutation thereof—check it out.

Marjorie Ingall is a former columnist for Tablet, the author of Mamaleh Knows Best, and a frequent contributor to the New York Times Book Review.