Europe’s Destructive Holocaust Shame

How the narrative of Israel as the new Nazis and Palestinians as the new Jews helps Western Europe avoid its culpability in World War II

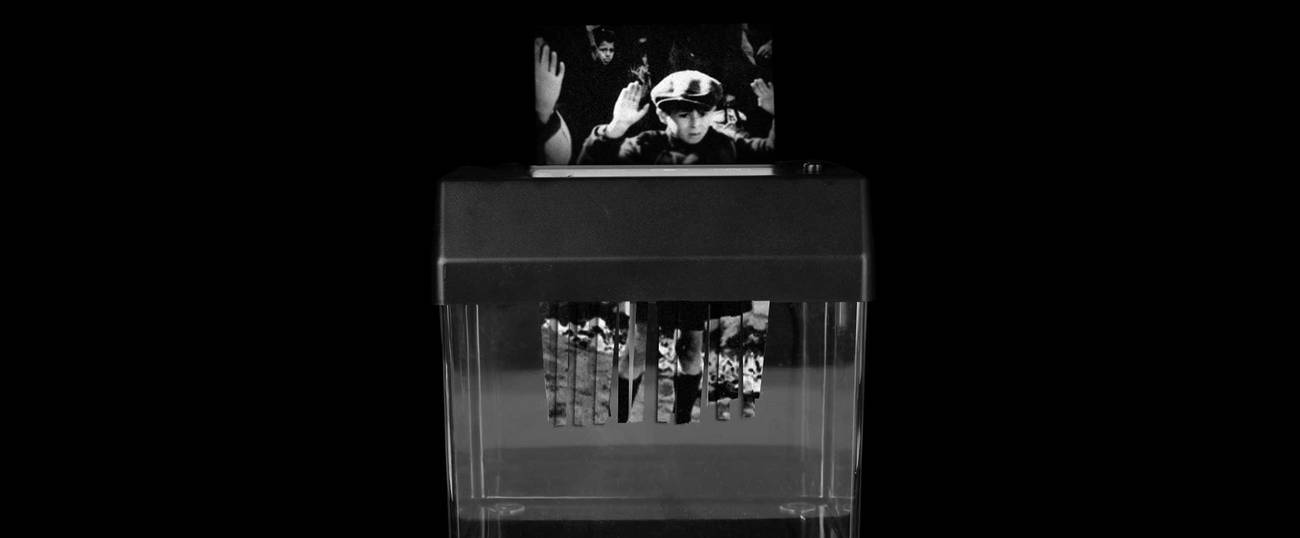

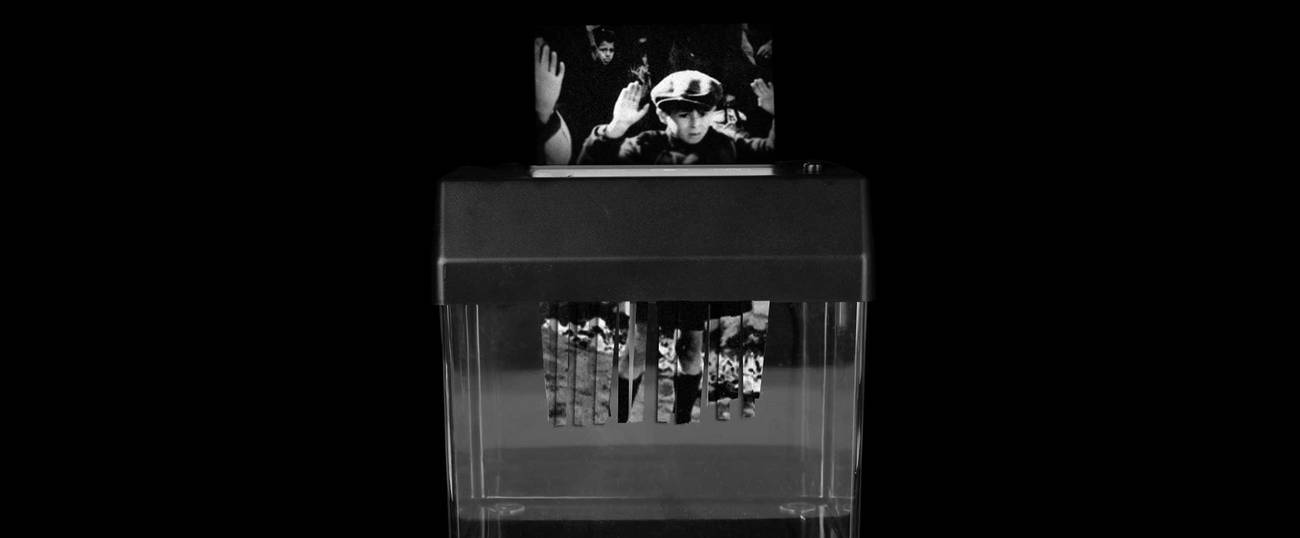

When I first heard about Catherine Nay—a prominent, mainstream, French journalist—stating on her Europe1 news program, in reference to the 2000 IDF killing of 12-year-old Muhammad al Durah in the arms of his father, that “with the symbolic charge [of the image of al Durah], Muhammad’s death cancels, erases the [famous WWII] picture of the Jewish boy, his hands up before the SS, in the Warsaw Ghetto,” I realized that Europeans had taken the story as a “get-out-of-Holocaust-guilt-free card.”

At the time I marveled—and continue to marvel—at the astounding folly of the statement. How can a brief, blurry, chopped up video of a boy who, at best was caught in a crossfire started by his own people firing behind him, at worst a lethal fake, eliminate—in fact, replace—a picture that symbolizes the systematic murder of over a million children and their families? How morally disoriented can one get? Apparently, the hope of escaping guilt is enough to induce people to adopt a supersessionist narrative: Israelis are the new Nazis, and Palestinians are the new Jews.

But the profound distinction between guilt and shame suggests that the right formula is “get-out-of-Holocaust-shame-free card.” Doesn’t sound as good. The difference: Guilt is an internally generated sense of moral obligation not to repeat past transgressions, like the extermination of a helpless minority within one’s own society. Shame, on the other hand, is externally generated, driven by the “shaming look” of others (the “honor-group”).

Therein lies a key difference: For guilt, it’s the awareness of the deed and its meaning; for shame, it’s whether others know. In some countries in the world, it’s not a question of whether you’re corrupt or not (everyone is, everyone knows), but whether you get caught. When Germans got caught carrying out genocide, their nation was not only guilty of the deed but shamed before the world … for committing such a hideous atrocity? … Or simply for getting caught?

While honor-shame cultures have moral codes, their vulnerability to the fear of shame can readily lead to a jettisoning of any moral concerns. After all, the limbic dread of shame—its disastrous psychological and practical impact—kicks in in times of humiliation and fear. Those afflicted with oneidophobia (overriding [limbic] fear of public blame/humiliation) are desperate that others not see, not know about, not talk about, what they have done; that one not bear the shame publicly, that one need not pay the steep price in social capital for one’s (mis)deeds.

Oneidophobes, people driven by shame-honor dynamics, avoid being subjected to criticism, especially public criticism. They consider both lying (to save face), and, where one can get away with it, violence (to regain respect), as normal recourse. Lancelot could publicly proclaim his innocence of adultery with the Queen because he killed everyone who accused him. Shame-driven oneidophobes want the negative spotlight off at all costs. In cases of those already shamed, they want to have the shame lifted.

Honest searching, motivated by well-deserved guilt, could have led post-Shoah Germans to become the most substantive academic critics of the Western grand narrative. After all, it wasn’t just European lunatics who disliked the Jews. How many great Western figures, when they bothered to mention the Jews, did so disparagingly, as the negative version of their great accomplishment? Instead of viewing this pattern of ancient, medieval, and modern—and now postmodern—denigration of Jews, as “they must be doing something to make others hate them so,” the self-critical German might have asked, “Maybe this has something to do with us and our problems?” German historians might have played a leading role in reinterpreting and integrating the story of the Jews into majority Western history, to a degree no earlier gentile historians had ever done.

***

Of all the post-modern multi-narrative projects, re-centering and problematizing Christian European majority narratives promised quite an academic bounty. The Hebraic contribution could be used to challenge the self-absorbed narcissistic quality of the modern Western grand narrative that so grated on the post-modern sensibility. Certainly, given the abundance of evidence and subjects to explore, it was a promising avenue for research. And how appropriate for Germans to engage in that exploration of a culture which, in their self-destructive madness, their fathers had tried to exterminate.

Some German theologian-scholars did explore the problematic nature of supersessionism. Indeed, the 1980s and ’90s saw a good deal of philo-Judaism in Europe—particularly in Germany. And certainly, in comparison with Japan, Germany went far in its acknowledgment of its guilt. The real issue, then, is how much of the public regret and debasement was an acceptance of shame (itself better than the Japanese refusal to even acknowledge what happened during the war), and how much of the acceptance of guilt.

And yet, in 2000, when the Western public sphere—now a global public sphere, itself an astounding creation—was split in two (right vs. left) by a civilizational crisis, both the public and the scholars whether they despised or admired Western history, showed astonishing incomprehension about the role of Jews—and Israel—in the creation and maintenance of a global civil society. If anything, the post-grand-narrativists, for whom the Western narrative is an ugly succession of oppression and injustice, see the national (autonomous) Jews (Israel) as the last remnant of the Western racist, imperial/colonial past. Israel ist unser Unglück (Israel is our misfortune). So instead of appreciating what these sovereign Jews were trying to handle (Jihad against infidels), they sought liberation from shame in embracing Palestinian terrorists, whom they welcomed as fellow victims of the vile, unbearably provocative behavior of the Jews.

For most major modern “thinkers” about “Western civilization,” the Jews were a marginal part of the tale, victims of lamentable Western intolerance (read: aggressive supersessionism), benefactors from, but not actual contributors to that great Western civilizing venture that brought us the modern world’s bounty of rights and freedoms and material abundance. I was astonished, when I finally got introduced to “Western Political Thought” as a post-doc fellow at Columbia (1984), to find that virtually everyone began this story with Socrates/Plato (5th-4th century BCE) and paid no attention to the Bible (12th century-6th century BCE) as a political document, despite its remarkably modern resonance. Instead, far too many of the great thinkers adopted the supersessionist tendency to define Jews and Judaism as the negative shadow of their great light.

Supersessionism, like all triumphalist religiosity, is shame-honor driven, hence its need to visibly dominate others. In the Western monotheistic/atheistic case, the belittling provides proof that one is at the moral cutting-edge of humanity. “We” are the true leaders with the true teaching. Do not listen to the chatterings of others. Thus, only a handful of (mostly Jewish) scholars have tilled these exceptionally rich fields of the Jewish/biblical origins of Western freedom and democracy.

How much stronger would Germans be today had their intellectual leadership worked on redeeming their guilt rather than escaping their shame?

Supersessionism worsens as it gets deliberately zero-sum: in order to prove my superiority over my parent, I will strive to degrade the remnant of those I (should) have surpassed and replaced. My self-identity as the moral leader of mankind demands the public humiliation of my rival, the more publicly, the better. What better way to resolve the anxiety of influence, than “killing” one’s begetter through systematic degradation?

This is my understanding of why the global progressive left has turned on Israel so savagely in the 21st century: in adopting the Israeli-Nazi/Palestinian-Jew replacement narrative, they manage to place themselves high above everyone else, not only the Arab Muslims, whom they see as far beneath them, worthy of pity, but more importantly the Jews, who have now, “lost the moral high ground.” The insatiable appetite of allegedly progressive people like Jostein Gaarder, for stories of autonomous Jews (Israelis) behaving badly, is nothing short of breathtaking. Indeed, an entire school of lethal journalists has emerged (and dominated coverage) in the 21st-century Middle East, precisely to feed that appetite.

When Europeans (or Christians) adopt the Palestinian replacement narrative, when the universalization of the Holocaust leads to silence about its prime victim; when academics and politicians engage in “Holocaust abuse” by replacing the (old) Jewish victim, with the (new) Palestinian or Muslim one, and denouncing Israel’s genocide against the Palestinians; they reveal that they are driven not by Holocaust guilt, but by Holocaust shame. The result is the exact opposite of what one might or should expect.

***

Hard, obsessional versions of the supersessionist anti-Jewish narrative can be found today at the extremes of both the right and the left—especially the intersectional left. But the less obvious forms of the shame-driven depreciation of Jews are not without their impact. The same Western Civ guys who consider Jews free-riders, benefiting from but not an agent in Western civilization, tend to also consider the creation of Israel a result of the Holocaust, rather than Jewish agency. At a time when the West does not know how to react to the assault of Caliphaters, would Europeans/Westerners not benefit from looking at Israel as an autonomous agent on the same side in the same struggle, rather than project upon her their own past sins?

In the mid-2000s, I spoke at a joint Jewish-German dialogue in Boston. I had been told by one of the organizers that the Germans were depressed, had no sense of purpose or identity about which they could be proud. I spoke to them about how their generation is best placed to tell the Arabs and the rest of the Muslim world to beware apocalyptic conspiracy theories like the Protocols of the Elders of Zion. Every German embassy and consulate, especially in the Arab and Muslim world, should, I argued, have a display, filled with the wisdom of German penitential awareness of how poisonous the impact of that forgery on the self-destructive German madness of their parents. Their past sins, I argued, had placed today’s Germans in a unique position from which to stand up against the rising tide of Jihadi anti-Semitism. Their response: “We didn’t come here to be fed Islamophobic nonsense.”

The Germans were not about to challenge the consensus, or maybe, to give up the thrilling moral titillation of having the Jews, the Israelis, take their place in the global hot-seat of shame and degradation. Years later, when I spent a year in Germany, I was surprised to hear Germans tell me, “We’re more afraid of our own fascism than that of our Muslims.” How much stronger would Germans be today had their intellectual leadership worked on redeeming their guilt rather than escaping their shame?

And that gets us to the core difference between guilt and shame: The shamed want nothing so much as to divest themselves of their shame, and if those onto whom they wish to shift the shame are also responsible for one’s shaming (as in “Europe will never forgive the Jews for the Holocaust“), then so much the better. Hence the Europeans with their global shame for the Holocaust, and the Arabs with their global shame for their massive civilizational failure, which is symbolized in their own eyes in their failure to strangle infant Israel in its cradle—both share a special supersessionist, shame-driven, eagerness to degrade Israel in order that the “Jewish State’s” shame will replace their own.

If Europe is to survive, to defend the remarkable freedoms and citizens’ rights it has already achieved, then it should turn away from Holocaust shame in favor of embracing guilt. Around 2010, a French publisher told me that a journalist had just asked him to choose a calendar date to commemorate “E.U.-Day.” Holocaust Day, he responded, an answer I found quite compelling because it was only in repentance for its treatment of Jews that Europeans were able to set behind them millennia of war and violence, and join together in a consensual, positive-sum union. Perhaps if he had been taken seriously, the EU would be better able to understand that the Jews and Israel are their best allies in the struggle for social justice and human freedom, instead of continuing a policy of strengthening its enemies and weakening its friends.

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Richard Landes, a historian living in Jerusalem, is chair of SPME’s Council of Scholars and a Senior Fellow at ISGAP. He is the author of Heaven on Earth: The Varieties of the Millennial Experience and Can “The Whole World” Be Wrong?: Lethal Journalism, Antisemitism and Global Jihad. He’s at Richard-Landes.com and on X @richard_landes.